Max Bruch | Chamber Music Trio Apollon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

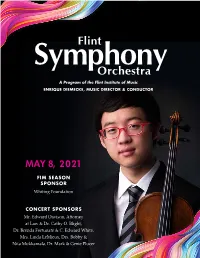

Flint Orchestra

Flint SymphonyOrchestra A Program of the Flint Institute of Music ENRIQUE DIEMECKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR MAY 8, 2021 FIM SEASON SPONSOR Whiting Foundation CONCERT SPONSORS Mr. Edward Davison, Attorney at Law & Dr. Cathy O. Blight, Dr. Brenda Fortunate & C. Edward White, Mrs. Linda LeMieux, Drs. Bobby & Nita Mukkamala, Dr. Mark & Genie Plucer Flint Symphony Orchestra THEFSO.ORG 2020 – 21 Season SEASON AT A GLANCE Flint Symphony Orchestra Flint School of Performing Arts Flint Repertory Theatre STRAVINSKY & PROKOFIEV FAMILY DAY SAT, FEB 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Cathy Prevett, narrator SAINT-SAËNS & BRAHMS SAT, MAR 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Noelle Naito, violin 2020 William C. Byrd Winner WELCOME TO THE 2020 – 21 SEASON WITH YOUR FLINT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA! BEETHOVEN & DVOŘÁK SAT, APR 10, 2021 @ 7:30PM he Flint Symphony Orchestra (FSO) is one of Joonghun Cho, piano the finest orchestras of its size in the nation. BRUCH & TCHAIKOVSKY TIts rich 103-year history as a cultural icon SAT, MAY 8, 2021 @ 7:30PM in the community is testament to the dedication Julian Rhee, violin of world-class performance from the musicians AN EVENING WITH and Flint and Genesee County audiences alike. DAMIEN ESCOBAR The FSO has been performing under the baton SAT, JUNE 19, 2021 @ 7:30PM of Maestro Enrique Diemecke for over 30 years Damien Escobar, violin now – one of the longest tenures for a Music Director in the country. Under the Maestro’s unwavering musical integrity and commitment to the community, the FSO has connected with audiences throughout southeast Michigan, delivering outstanding artistry and excellence. All dates are subject to change. -

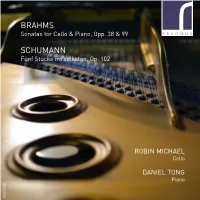

Brahms Schumann

BRAHMS Sonatas for Cello & Piano, Opp. 38 & 99 SCHUMANN Fünf Stücke im Volkston, Op. 102 ROBIN MICHAEL Cello DANIEL TONG Piano RES10188 Brahms & Schumann Works for Cello & Piano Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Sonata No. 1 for Cello and Piano in E minor, Op. 38 1. Allegro non troppo [13:26] 2. Allegretto quasi menuetto [5:37] Robin Michael cello 3. Allegro [6:23] Daniel Tong piano Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Fünf Stücke im Volkston, Op. 102 Cello by Stephan von Baehr (Paris, 2010), after Matteo Goffriller (1695) (Five Pieces in Folk Style) Bow by Noel Burke (Ireland, 2012), after François Xavier Tourte (1820) 4. Vanitas vanitatum [2:57] 5. Langsam [3:24] Blüthner Boudoir Grand Piano thought to have been played and 6. Nicht schnell, mit viel Ton zu spielen [3:56] selected by Brahms, Serial No. 45615 (1897) 7. Nicht zu rasch [1:54] 8. Stark und markiert [3:08] Johannes Brahms Sonata No. 2 for Cello and Piano in F major, Op. 99 9. Allegro vivace [8:51] 10. Adagio affettuoso [6:21] 11. Allegro passionato [6:51] 12. Allegro molto [4:41] About Robin Michael: Total playing time [67:35] ‘Michael played with fervour, graceful finesse and great sensitivity’ The Strad About Daniel Tong: ‘[...] it’s always a blessed relief to hear an artist with Daniel Tong’s self-evident love and understanding of the instrument’ BBC Music Magazine Brahms & Schumann: inventiveness and in its firm but delicately Works for Cello & Piano detailed structure.’ The first copies of the published sonata appeared in August 1866, Brahms started work on his Cello Sonata No. -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

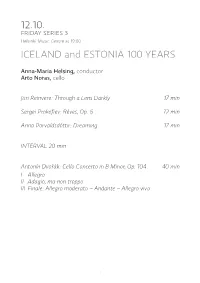

12.10. ICELAND and ESTONIA 100 YEARS

12.10. FRIDAY SERIES 3 Helsinki Music Centre at 19:00 ICELAND and ESTONIA 100 YEARS Anna-Maria Helsing, conductor Arto Noras, cello Jüri Reinvere: Through a Lens Darkly 17 min Sergei Prokofiev: Rêves, Op. 6 12 min Anna Þorvaldsdóttir: Dreaming 17 min INTERVAL 20 min Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 40 min I Allegro II Adagio, ma non troppo III Finale: Allegro moderato – Andante – Allegro vivo 1 The LATE-NIGHT CHAMBER MUSIC will begin in the main Concert Hall after an interval of about 10 minutes. Those attending are asked to take (unnumbered) seats in the stalls. Paula Sundqvist, violin Tuija Rantamäki, cello Sonja Fräki, piano Antonín Dvořák: Piano Trio “Dumky” 31 min 1. Lento maestoso – Allegro vivace – Allegro molto 2. Poco adagio – Vivace 3. Andante – Vivace non troppo 4. Andante moderato – Allegretto scherzando – Allegro 5. Allegro 6. Lento maestoso – Vivace Interval at about 20:00. The concert will end at about 21:15, the late-night chamber music at about 22:00. Broadcast live on Yle Radio 1 and Yle Areena. It will also be shown in two parts in the programme “RSO Musiikkitalossa” (The FRSO at the Helsinki Music Centre) on Yle Teema on 21.10. and 4.11., with a repeat on Yle TV 1 on 27.10. and 10.11. 2 JÜRI REINVERE director became a close friend and im- portant mentor of the young compos- (b. 1971): THROUGH A er. Theirs was not simply a master-ap- LENS DARKLY prenticeship relationship, for they often talked about music, and Reinvere would Jüri Reinvere has been described as a sometimes express his own views as a true cosmopolitan with Estonian roots. -

Double Bass Sound Christine Hoock

MOZARTEUM DOUBLE BASS SOUND CHRISTINE HOOCK RECORDS MOZARTEUM DOUBLE BASS SOUND – Christine Hoock Die CD-Reihe „Mozarteum-Sound“ hat es sich ten und Studierenden ihrer Klasse im Fokus dieser zum Ziel gesetzt, hervorragende künstlerische Aufnahme. Als Partner standen ihr bei der Reali- Leistungen wie auch eine besondere Klangästhetik sierung dieses breitgefächerten Repertoires Hans- – immer in Bezug auf ein bestimmtes Instrument jörg Angerer (Chefdirigent der Bläserphilharmonie – an der Universität Mozarteum Salzburg zu do- Mozarteum Salzburg), Benjamin Schmid (Violine), kumentieren. Mari Kato (Klavier), Ariane Haering (Klavier), Bar- bara Nussbaum (Klavier) und DJ UmbertoEcho (Mi- Diesmal dem Kontrabass mit seiner außerordent- xing Desk) zur Seite. lichen Beweglichkeit, seinem Farbenreichtum und seiner Virtuosität – dabei oft nahezu archaische Klangwelten erschaffend – gewidmet, steht die au- ßergewöhnliche Kontrabass-Künstlerin Christine Hoock gemeinsam mit Absolventinnen/Absolven- MOZARTEUM DOUBLE BASS SOUND – Christine Hoock The CD series Mozarteum Sound aims to docu- the Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg), ment excellent artistic achievements at the Moz- Benjamin Schmid (violin), Mari Kato (piano), Ariane arteum University as well as a particular kind of Haering (piano), Barbara Nussbaum (piano) and aesthetic sound, always related to a certain in- DJ UmbertoEcho (mixing desk). strument. This recording is devoted to the double bass and reveals its extraordinary fl exibility, rich colours and virtuosity, and features the outstanding double bass player Christine Hoock, together with graduates and students from her class. Partners in the realization of this broad repertoire were Hansjörg Angerer (principal conductor of 1 1 CHRISTINE HOOCK „... jeder entscheidet sich intuitiv für das Instru- Dies spiegelt sich auch in ihrer abwechslungsrei- Die Preisträgerin internationaler Wettbewerbe ar- Christine Hoock leitet die Internationale Johann- ment, dessen Tonhöhe und Klangfarbe seine innere chen Diskographie wieder. -

Download (1MB)

BYRON'S LETTERS AND JOURNALS Byron's Letters and Journals A New Selection From Leslie A. Marchand's twelve-volume edition Edited by RICHARD LANSDOWN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © In the selection, introduction, and editorial matter Richard Lansdown 2015 © In the Byron copyright material John Murray 1973-1982 The moral rights of the author have be en asserted First Edition published in 2015 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publicationmay be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writi ng of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press i98 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2014949666 ISBN 978-0-19-872255-7 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives pk in memory of Dan Jacobson 1929-2014 'no one has Been & Done like you' ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Two generations of Byron scholars, biographers, students, and readers have acknowledged the debt they owe to Professor Leslie A. -

Rep List 1.Pub

Richmond Symphony Orchestra League Student Concerto Competition Repertoire Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Guitar & percussion students are welcome to participate; Please contact Anne Hoffler, contest coordinator, at aahoffl[email protected] for repertoire approval no later than November 30. VIOLIN Faure Elegy, Op. 24 Bach All Violin concerti Haydn Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major Beethoven Violin Concerto in D major Haydn Cello Concerto No. 2 in D major Beethoven Romance No. 1 in G major Kabalevsky Cello Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 49 Beethoven Romance No. 2 in F major Lalo Cello Concerto in D minor Bériot Scéne de Ballet, Op. 100 Rubinstein Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op.96 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 7 in G major Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op.33 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 9 in A minor Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 119 Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor Schumann Cello Concerto in A minor Haydn All Violin concerti Shostakovich Concerto for Cello No. 1 Kabalevsky Violin Concerto in C Major, Op. 48 Stamitz All Cello concerti Lalo Symphonie Espagnole R. Strauss Romanze in F major Massenet Méditation from Thaïs Tchaikovsky Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op.33 Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 Vivaldi All Cello concerti Mozart Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat major Mozart Violin Concerto No. 2 in D major BASS Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major Bottesini Double Bass Concerto No.2 in B minor Mozart Violin Concerto No. -

String Diplomas Repertoire List

String diplomas repertoire list 1 January 2011 – 31 December 2018 STRING DIPLOMAS 2011–2018 Contents Page LCM Publications ........................................................................................................................ 2 Overview of LCM Diploma Structure ................................................................................. 3 Violin DipLCM in Performance .......................................................................................................... 4 ALCM in Performance .............................................................................................................. 5 LLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 7 FLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 7 Viola DipLCM in Performance .......................................................................................................... 8 ALCM in Performance .............................................................................................................. 9 LLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 10 FLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 11 Cello DipLCM in Performance ......................................................................................................... -

Wichita Symphony Youth Orchestras Acceptable Repertoire for Youth Talent Auditions

Wichita Symphony Youth Orchestras Acceptable Repertoire for Youth Talent Auditions Repertoire not listed below may be acceptable, but must be pre-approved. Contact Tiffany Bell at [email protected] to request approval for repertoire not on this list. Violin Bach: Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Bach: Concerto No. 2 in E Major Barber: Concerto, Op. 14, first movement Beethoven: Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 Beethoven: Romance No. 1 in G Major Beethoven: Romance No. 2 in F Major Brahms: Concerto, third movement Bruch: Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 26, any movement Bruch: Scottish Fantasy Conus: Concerto in E Minor, first movement Dvorak: Romance Haydn: Concerto in C Major, Hob.VIIa Kabalevsky: Concerto, Op. 48, first or third movement Khachaturian: Violin Concert, Allegro Vivace, first movement Lalo: Symphonie Espagnole, first or fifth movement Mendelssohn: Concerto in E Minor, any movement Mozart: Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216, any movement Mozart: Concerto No. 4 in D Major, K. 218, first movement Mozart: Concerto No. 5 in A Major, K. 219, first movement Saint-Saens: Introduction and Rondo Capriccios, Op. 28 Saint-Saens: Concerto No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 61 Saint-Saens: Havanaise Sarasate: Zigeunerweisen, Op. 20 Sibelius: Concerto in D Minor, fist movement Tchaikovsky: Concerto, third movement Vitali: Chaconne Wieniawski: Legend, Op. 17 Wieniawski: Concerto in D Minor Viola J.C. Bach/Casadesus: Concerto in C Minor, Adagio-Allegro Bach: Concerto in D Minor, first movement Forsythe: Concerto for Viola, first movement Handel/Casadesus: Concerto in B Minor Hoffmeister Concerto Stamitz: Concerto in D Major Telemann: Concerto in G Major Cello Boccherini: Concerto Bruch: Kol Nidrei Dvorak: Concerto in B Minor, Op. -

Scottish Fantasy

JOSHUA BELL BRUCH Scottish Fantasy Academy of St Martin in the Fields Br uc h (1838-1920) SCOTTISH FANTASY FOR VIOLIN AND ORCHESTRA, OP. 46 1 I. Introduction: Grave, Adagio cantabile 2 II. Scherzo: Allegro 3 III. Andante sostenuto 4 IV. Finale: Allegro guerriero VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1 IN G MINOR, OP. 26 5 I. Vorspiel: Allegro moderato 6 II. Adagio 7 III. Finale: Allegro energico Joshua Bell, Soloist/Director Academy of St Martin in the Fields Master of More than Melody The works presented here are two out of the three pieces by Max Bruch that can be called staples of the classical repertoire. (The third is his piece for cello and orchestra, Kol Nidrei.) In his lifetime he was best known for large-scale choral works, well received at their premieres and popular with the many amateur choral societies found throughout Europe in the later 19th century. Those choruses began to dwindle once the 20th century got underway. As they disappeared, Bruch’s cantatas and oratorios also faded from consciousness, rarely, if ever, to be heard again. By association, Bruch became thought of as a composer whose time had come and gone. It is interesting to compare the very diff erent assessments of him in two successive editions of Grove’s Dictionary of Music, from 1904 and 1954. The earlier edition declared: “He is above all a master of melody, and of the eff ective treatment of masses of sound.” By 1954 the verdict on his output was dismissive and condescending: ‘It is its lack of adventure that limited its fame.’ Bruch was born during the lifetimes of Mendelssohn and Schumann and died when Schoenberg and Stravinsky were creating gigantic waves in musical life. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito.