Scottish Fantasy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flint Orchestra

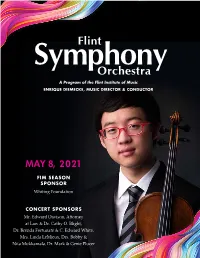

Flint SymphonyOrchestra A Program of the Flint Institute of Music ENRIQUE DIEMECKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR MAY 8, 2021 FIM SEASON SPONSOR Whiting Foundation CONCERT SPONSORS Mr. Edward Davison, Attorney at Law & Dr. Cathy O. Blight, Dr. Brenda Fortunate & C. Edward White, Mrs. Linda LeMieux, Drs. Bobby & Nita Mukkamala, Dr. Mark & Genie Plucer Flint Symphony Orchestra THEFSO.ORG 2020 – 21 Season SEASON AT A GLANCE Flint Symphony Orchestra Flint School of Performing Arts Flint Repertory Theatre STRAVINSKY & PROKOFIEV FAMILY DAY SAT, FEB 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Cathy Prevett, narrator SAINT-SAËNS & BRAHMS SAT, MAR 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Noelle Naito, violin 2020 William C. Byrd Winner WELCOME TO THE 2020 – 21 SEASON WITH YOUR FLINT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA! BEETHOVEN & DVOŘÁK SAT, APR 10, 2021 @ 7:30PM he Flint Symphony Orchestra (FSO) is one of Joonghun Cho, piano the finest orchestras of its size in the nation. BRUCH & TCHAIKOVSKY TIts rich 103-year history as a cultural icon SAT, MAY 8, 2021 @ 7:30PM in the community is testament to the dedication Julian Rhee, violin of world-class performance from the musicians AN EVENING WITH and Flint and Genesee County audiences alike. DAMIEN ESCOBAR The FSO has been performing under the baton SAT, JUNE 19, 2021 @ 7:30PM of Maestro Enrique Diemecke for over 30 years Damien Escobar, violin now – one of the longest tenures for a Music Director in the country. Under the Maestro’s unwavering musical integrity and commitment to the community, the FSO has connected with audiences throughout southeast Michigan, delivering outstanding artistry and excellence. All dates are subject to change. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

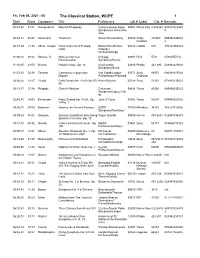

Fri, Feb 05, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 31:51 Humperdinck Moorish Rhapsody Czecho-Slovak Radio 00509 Marco Polo 8.223369 489103023363 Symphony/Fischer-Die 0 skau 00:34:2102:08 Schumann Traumerei Alexis Weissenberg 07843 Virgin 234865 509992348652 Classics 2 00:37:2921:34 White, Joseph Violin Concerto in F sharp Barton Pine/Encore 04328 Cedille 035 735131903523 minor Chamber Orchestra/Hege 01:00:23 08:32 Strauss, R. Waltzes from Der Chicago 00458 RCA 5721 07863557212 Rosenkavalier Symphony/Reiner 01:10:0542:05 Berlioz Harold in Italy, Op. 16 Imai/London 02693 Philips 442 290 028944229028 Symphony/Davis 01:53:20 05:30 Thomas Connais-tu le pays from Von Stade/London 05873 Sony 89370 696998937024 Mignon Philharmonic/Pritchard Classical 02:00:2013:27 Vivaldi Cello Sonata No. 4 in B flat, RV Anner Bylsma 05188 Sony 51350 074645135021 45 02:15:17 27:48 Respighi Church Windows Cincinnati 08438 Telarc 80356 089408035623 Symphony/Lopez-Cob os 02:44:3514:08 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 9 in E, Op. John O'Conor 05592 Telarc 80293 089408029325 14 No. 1 03:00:1307:50 Balakirev Islamey, an Oriental Fantasy USSR 05750 Melodiya 34165 743213416526 Symphony/Svetlanov 03:09:0308:02 Debussy 3rd mvt (Andantino) from String Ysaye Quartet 09850 Decca 478 3691 028947836919 Quartet in G minor, Op. 10 03:18:1540:32 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. Ma/NY 03691 Sony 67173 074646717325 104 Philharmonic/Masur 04:00:1712:51 Alfven Swedish Rhapsody No. -

Verdehr Trio Verdehr Trio

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 2-22-1991 Concert: Verdehr Trio Verdehr Trio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Verdehr Trio, "Concert: Verdehr Trio" (1991). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5582. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5582 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College ITHACA School of Music ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1990-91 VERDEHR TRIO Walter Verdehr, violin Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr, clarinet Gary Kirkpatrick, piano CREATURES OF PROMETHEUS, op. 43 Ludwig van Beethoven No. 14 Andante and Allegretto (1770-1827) EIGHT PIECES FOR CLARINET, VIOLA AND PIANO, op. 83 Max Bruch (1838-1920) transcribed by Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr VI. Nachtgesang: Andante con moto (Nocturn) IV. Allegro agitato A TRIO SETTING (19<JO) Gwither SchQller (b. 1925) Fast and Explosive Slow and Dreamy Allegretto; Scherzando e Leggiero IN1ERMISSION SONATA A TRE (1982) KarelHusa (b.1921) Con intensita Con sensitivita Con velocita SLAVONIC DANCES Antonin Dvofak (1841-1904) Tempo di Menuetto, op. 46, no. 2 Allegretto grazioso, op. 72, no. 2 Presto, op. 46, no. 8 Walter Ford Hall Auditorium Friday, February 22, 1991 8:15 p.m. PROGRAM NOTES Ludwig van Beethoven. Creatures of Prometheus, op. 43 The Andante and Allegretto, op. 43, no. 14 by Beethoven is taken from the ballet Creatures of Prometheus, op. 43. Written in 1800-1801, it was Beethoven's introduction to the Viennese stage and the first performance was given in the Burgtheater in Vienna on March 28, 1801. -

Masterpieces Celebrating the Human Journey Music by Barber, Bruch, Ravel, Prokofiev and Piazzolla

Masterpieces Celebrating the Human Journey Music by Barber, Bruch, Ravel, Prokofiev and Piazzolla Aude Castagna, Concert director and cello Vlada Volkova, piano; Jeff Gallagher, clarinet Shannon Delaney and Brian Johnston, violins Eleanor Angel, viola The Music Nostalgia: Prokofiev, Overture on Hebrew Themes (1919) Sergei Prokofiev wrote the Overture on Hebrew Themes, Op. 34, in 1919, during a trip to the United States. The piece was commissioned by a Russian sextet, the Zimro Ensemble, sponsored by the Russian Zionist Organization and was written for the unusual combination of clarinet, string quartet, and piano. The members had just arrived in America from the Far East on a world tour and gave Prokofiev a notebook of Jewish folksongs. The melodies Prokofiev chose have never been traced to any authentic sources and may have been actually composed by the ensemble’s clarinetist in the Jewish style. Its structure follows the form of a fairly conventional overture. It is in the key of C minor. The first theme, un poco allegro, has a jumpy and festive rhythm, unmistakably evoking klezmer music by alternating low and high registers and using repeated swelling and tapering of volume. The second theme, piu mosso, is a nostalgic cantabile theme introduced by the cello and then passed to the first violin. Dreams of Love: Eight Pieces for Clarinet, Cello, & Piano, (1910) Op. 83 by Max Bruch Numbers 1, 2,5, 6 and 7. Max Bruch (1838-1920) received his earliest music instruction from his mother, a noted singer and pianist. He was widely known and respected in his day as a composer, conductor, and teacher. -

Rep List 1.Pub

Richmond Symphony Orchestra League Student Concerto Competition Repertoire Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Guitar & percussion students are welcome to participate; Please contact Anne Hoffler, contest coordinator, at aahoffl[email protected] for repertoire approval no later than November 30. VIOLIN Faure Elegy, Op. 24 Bach All Violin concerti Haydn Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major Beethoven Violin Concerto in D major Haydn Cello Concerto No. 2 in D major Beethoven Romance No. 1 in G major Kabalevsky Cello Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 49 Beethoven Romance No. 2 in F major Lalo Cello Concerto in D minor Bériot Scéne de Ballet, Op. 100 Rubinstein Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op.96 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 7 in G major Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op.33 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 9 in A minor Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 119 Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor Schumann Cello Concerto in A minor Haydn All Violin concerti Shostakovich Concerto for Cello No. 1 Kabalevsky Violin Concerto in C Major, Op. 48 Stamitz All Cello concerti Lalo Symphonie Espagnole R. Strauss Romanze in F major Massenet Méditation from Thaïs Tchaikovsky Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op.33 Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 Vivaldi All Cello concerti Mozart Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat major Mozart Violin Concerto No. 2 in D major BASS Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major Bottesini Double Bass Concerto No.2 in B minor Mozart Violin Concerto No. -

String Diplomas Repertoire List

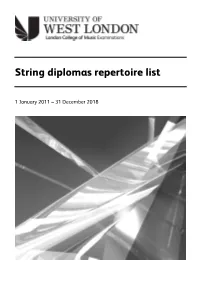

String diplomas repertoire list 1 January 2011 – 31 December 2018 STRING DIPLOMAS 2011–2018 Contents Page LCM Publications ........................................................................................................................ 2 Overview of LCM Diploma Structure ................................................................................. 3 Violin DipLCM in Performance .......................................................................................................... 4 ALCM in Performance .............................................................................................................. 5 LLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 7 FLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 7 Viola DipLCM in Performance .......................................................................................................... 8 ALCM in Performance .............................................................................................................. 9 LLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 10 FLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 11 Cello DipLCM in Performance ......................................................................................................... -

Wichita Symphony Youth Orchestras Acceptable Repertoire for Youth Talent Auditions

Wichita Symphony Youth Orchestras Acceptable Repertoire for Youth Talent Auditions Repertoire not listed below may be acceptable, but must be pre-approved. Contact Tiffany Bell at [email protected] to request approval for repertoire not on this list. Violin Bach: Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Bach: Concerto No. 2 in E Major Barber: Concerto, Op. 14, first movement Beethoven: Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 Beethoven: Romance No. 1 in G Major Beethoven: Romance No. 2 in F Major Brahms: Concerto, third movement Bruch: Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 26, any movement Bruch: Scottish Fantasy Conus: Concerto in E Minor, first movement Dvorak: Romance Haydn: Concerto in C Major, Hob.VIIa Kabalevsky: Concerto, Op. 48, first or third movement Khachaturian: Violin Concert, Allegro Vivace, first movement Lalo: Symphonie Espagnole, first or fifth movement Mendelssohn: Concerto in E Minor, any movement Mozart: Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216, any movement Mozart: Concerto No. 4 in D Major, K. 218, first movement Mozart: Concerto No. 5 in A Major, K. 219, first movement Saint-Saens: Introduction and Rondo Capriccios, Op. 28 Saint-Saens: Concerto No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 61 Saint-Saens: Havanaise Sarasate: Zigeunerweisen, Op. 20 Sibelius: Concerto in D Minor, fist movement Tchaikovsky: Concerto, third movement Vitali: Chaconne Wieniawski: Legend, Op. 17 Wieniawski: Concerto in D Minor Viola J.C. Bach/Casadesus: Concerto in C Minor, Adagio-Allegro Bach: Concerto in D Minor, first movement Forsythe: Concerto for Viola, first movement Handel/Casadesus: Concerto in B Minor Hoffmeister Concerto Stamitz: Concerto in D Major Telemann: Concerto in G Major Cello Boccherini: Concerto Bruch: Kol Nidrei Dvorak: Concerto in B Minor, Op. -

Thursday Playlist

February 6, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.” — Igor Stravinsky Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Reference 00:01 Buy Now! Saint-Saëns Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso, Op. 28 Geller/Kansas City Symphony/Stern 136 030911113629 Awake! Recordings 00:11 Buy Now! Alfven Suite ~ The Mountain King, Op. 37 Royal Opera Orchestra Stockholm/Alfvén Swedish Society 1003 N/A Scottish Fantasy for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 00:29 Buy Now! Bruch Ehnes/Montreal Symphony/Bernardi CBC 5222 059582522226 46 01:00 Buy Now! Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Arrau/London Philharmonic/Inbal Decca 478 0108 028947801085 01:36 Buy Now! Bach Trio Sonata in C, BWV 529 Balsom/Ibragimova/Caudle/Ross EMI 58047 724355804723 01:51 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Hebrides Overture, Op. 26 Freiburg Baroque Orchestra/Heras-Casado Harmonia Mundi 90235 3149020232521 02:02 Buy Now! Berwald Symphony No. 3 in C, "Sinfonie singuliere" Royal Philharmonic/Bjorlin EMI 00920 5099950092024 02:33 Buy Now! Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 19 in G minor, Op. 49 No. 1 John O'Conor Telarc 80293 089408029325 02:42 Buy Now! Bizet L'Arlesienne Suite No. 1 Berlin Philharmonic/Karajan DG 415 106 028921510624 03:01 Buy Now! Strauss, R. Waltzes ~ Der Rosenkavalier Slovak Philharmonic/Kosler Naxos 8.578041-42 747313804177 03:14 Buy Now! Bridge An Irish Melody English String Orchestra/Boughton Nimbus 5366 083603536626 03:23 Buy Now! Mozart String Quartet No. 23 in F, K. 590 Mosaic Quartet Auvidis Astree 8659 3298490086599 03:59 Buy Now! Debussy The Sunken Cathedral ~ Preludes, Book I Gerhard Oppitz RCA 61968 090266196821 04:08 Buy Now! Bach, C.P.E. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Jae Cosmos Lee, Violin

“CELLISSIMO” PROGRAM NOTES By Jae Cosmos Lee, Violin Max Brush (1838 – 1920) At the urging of the beginning with a slow introduction, which is Cello virtuoso Robert Hausmann, the an example of Beethoven breaking off from German Romantic composer, Max Bruch the normal fast movement form, especially completed his op.47, Kol Nidrei (the in the last movement of an instrumental Aramaic phrase, which means All Vows, and work. Moreover, the entire third movement is the incantation that starts the Yom Kippur is in E major, which is the dominant key from service) in 1880 and publishing it a year later the original A major that the first movement in Berlin. Along with his first Violin is written in, which at the time was Concerto, this composition, originally for considered highly unconventional. The A Cello and Orchestra, is one of his most minor Scherzo, which comprises the second beloved and widely performed pieces. For movement, is in the parallel minor to the that reason, it led the German National opening movement's key, which can also be Socialist Party during the 1930's to assume considered Beethoven going against the that Bruch was of Jewish origin and banned grain of his Viennese contemporaries. his music until Germany's defeat in the Second World War. Fortunately, for Bruch, who was raised Protestant, and whose ancestors were not Jewish, his music Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) at age 57, survived the persecution and Kol Nidrei is earnestly contemplated retirement from still firmly planted in the canon of every composing after the premiere of his String cellist. -

JONGEN: Danse Lente for Flute and Harp Notes on the Program by Noel Morris ©2021

JONGEN: Danse lente for Flute and Harp Notes on the Program By Noel Morris ©2021 en years ago, a video of a Jongen’s Sinfonia is a masterpiece, a tour de crowded department store force celebrated by organists around the at Christmastime went world. Unfortunately, due to a series of Tviral. In it, holiday shoppers mishaps, the Sinfonia waited more suddenly find themselves than 80 years for a performance on awash in music—a thundering the Wanamaker Organ. rendition of the Hallelujah Chorus. The video shows Today, Jongen is best bewildered customers, remembered as an organ store clerks and live singers composer, although he wrote shuffling about in a chamber works, a symphony gleeful heap. It happened and concertos, among other at a Philadelphia Macy’s things. It’s only been in recent (formerly Wanamaker’s), years that musicians have begun home of the world’s largest to explore Jongen’s other works. pipe organ. From an early age, Jongen The Wanamaker Organ was the excelled at the piano and began to crown jewel of one of America’s dabble in composition; he entered first department stores. During the the Liège Conservatory at age seven 1920s, Rodman Wanamaker paid to and continued his studies into his twenties. have the instrument refurbished and enlarged During the 1890s he worked as a church organist to 28,482 pipes and decided to commission some around Liège and later joined the faculty at the new music for its rededication. He chose the famous Conservatory. After the German army invaded Belgium Belgian organist Joseph Jongen, who responded in 1914, he took his family to England where he formed with his Sinfonia concertante (1926), a piece the a piano quartet and traveled the UK, entertaining a composer would later refer to as “that unfortunate war weary people. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Mathematical and Musical Analysis of Kol Nidrei

Mathematical and Musical Analysis of Kol Nidrei Kol Nidrei, Op. 47, is an instrumental piece written in 1881 by Max Bruch. It was originally composed for violincello and orchestra, though the version that will be analyzed here is a translation for viola and piano. Though Bruch was a protestant, he composed Kol Nidrei by drawing from two themes of Jewish descent. The first theme is featured in the opening melody and throughout the D minor section of the piece. It is based on the Kol Nidre prayer, which is an old Hebrew prayer of atonement that is recited on the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur. The melody of this theme is meant to imitate the voice of a hazzan, who leads the worship of the congregation through lyrical prayer in a synagogue. The second theme is featured in the second half of the piece, where the music switches from D minor to D major. This theme draws from a section of a Hebrew melody titled “O Weep for Those that Wept on Babel’s Stream” by Lord Byron. Bruch composed Kol Nidrei in the romantic era of music. It was in this era that composers strayed from previous musical conventions and rules in order to create pieces consisting of significant emotional expression. Because of this, Kol Nidrei breaks many musical rules by utilizing irregular phrasing, disjunct harmonies, and little repetition in the melodic line. This lack of consistency makes it a difficult piece to examine, though spectrograms are able to help illustrate exactly what is heard in this piece. Since Kol Nidrei has such emotional themes, the solo violist can enhance the emotion using vibrato.