Max Bruch (1838-1920) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in G Minor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

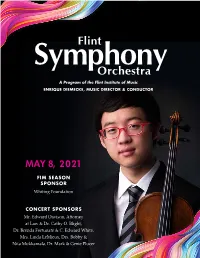

Flint Orchestra

Flint SymphonyOrchestra A Program of the Flint Institute of Music ENRIQUE DIEMECKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR MAY 8, 2021 FIM SEASON SPONSOR Whiting Foundation CONCERT SPONSORS Mr. Edward Davison, Attorney at Law & Dr. Cathy O. Blight, Dr. Brenda Fortunate & C. Edward White, Mrs. Linda LeMieux, Drs. Bobby & Nita Mukkamala, Dr. Mark & Genie Plucer Flint Symphony Orchestra THEFSO.ORG 2020 – 21 Season SEASON AT A GLANCE Flint Symphony Orchestra Flint School of Performing Arts Flint Repertory Theatre STRAVINSKY & PROKOFIEV FAMILY DAY SAT, FEB 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Cathy Prevett, narrator SAINT-SAËNS & BRAHMS SAT, MAR 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Noelle Naito, violin 2020 William C. Byrd Winner WELCOME TO THE 2020 – 21 SEASON WITH YOUR FLINT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA! BEETHOVEN & DVOŘÁK SAT, APR 10, 2021 @ 7:30PM he Flint Symphony Orchestra (FSO) is one of Joonghun Cho, piano the finest orchestras of its size in the nation. BRUCH & TCHAIKOVSKY TIts rich 103-year history as a cultural icon SAT, MAY 8, 2021 @ 7:30PM in the community is testament to the dedication Julian Rhee, violin of world-class performance from the musicians AN EVENING WITH and Flint and Genesee County audiences alike. DAMIEN ESCOBAR The FSO has been performing under the baton SAT, JUNE 19, 2021 @ 7:30PM of Maestro Enrique Diemecke for over 30 years Damien Escobar, violin now – one of the longest tenures for a Music Director in the country. Under the Maestro’s unwavering musical integrity and commitment to the community, the FSO has connected with audiences throughout southeast Michigan, delivering outstanding artistry and excellence. All dates are subject to change. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Selections from Eight Pieces for Clarinet, Viola and Piano, Op. 83 Max Bruch

concerto for two pianos, various chamber pieces, songs, three operas and much choral music. Bruch composed his Eight Pieces for Clarinet, Viola and Piano, Op. 83 in 1909, in his seventieth year, for his son Max Felix, a talented clarinetist who also inspired a Double Concerto (Op. 88) for his instrument and viola from his father two years later. When the younger Bruch played the works in Cologne and Hamburg, Fritz Steinbach reported favorably on the event to the composer, comparing Max Felix’s ability with that of Richard Mühlfeld, the clarinetist who had inspired two sonatas, a quintet and a trio from Johannes Brahms two decades before. Clarinet and viola are here evenly matched, singing together in duet or conversing in dialogue, while the piano serves as an accompanimental partner. Bruch intended that the Eight Pieces be regarded as a set of independent miniatures of various styles rather than as an integrated cycle, and advised against playing all of them together in concert. The Pieces (they range from three to six minutes in length) are straightforward in structure — binary (A-B) or ternary (A-B-A) for the first six, compact sonata form for the last two — and are, with one exception (No. 7), all in thoughtful minor keys. Though Bruch was fond of incorporating folk music into his concert works, only the Romanian Melody (No. 5, Selections from Eight Pieces suggested to him, he said, by “the delightful young princess zu Wied” at one of his Sunday open-houses; he dedicated the work to her) shows such for Clarinet, Viola and Piano, Op. -

Beethoven Room - 706 | August 30, 2020

Beethoven Room - 706 | August 30, 2020 Welcome to the listing for Honors 2020. This is just a supplemental reference. All participating students have received their log on information via email. 2PM Recital Tyrus Chuang Aram Khachaturian - Sonatina 1 Piano Ryan Cheng Bach - Allemande from Violin Partita in D minor BWV 1004 Violin Shreya Nabar Mozart- Allegro Flute Vienna Parnell Mozart - Sonata in c minor, K. 457 Piano Petr Tupitsyn Rachmaninov - Vocalise Flute Jessica Li Frederic Chopin - Nocturne in B major, Op. 32, No. 1 Piano Fanya Xu Enrique Granados, Playera Piano Emily Harn Serge Prokofiev - Prelude in C Major Piano Lazypotato Ying Edvard Grieg - Bells Ringing Piano Kayla Tan Zez Confrey - Coaxing the Piano Piano Amber Kuo Gabriel Fauré - Sicilienne, Op. 78 Flute James Tsaggaris Frédéric Chopin - Fantaisie-Impromptu in C♯ minor Op. 66 Piano 3PM Recital Max Tan Haydn - Sonata in E Flat Major Hob XVI:52 No. 62, 3. Presto Piano Sean Daly G. Lange - Blumenlied Piano Satina Guo Fazil Say - Jazz Fantasy on Mozart Piano Claire Law Gershwin - Prelude No. 1 Piano Calvin Park Bach - Invention No. 13 Piano Phuong-Nghi Nguyen Albert Ginastera-Trieste from Twelve American Preludes, Op.12 Piano Rithika Ramesh Gretchaninoff - Chant d'Automne Piano Maggie Cong Ludwig van Beethoven - Sonata Op. 79 Piano Eric Lee Max Bruch - Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, I. Vorspiel Violin Jocelyn Gou Friedrich Kuhlau - Sonatina in C, Op. 55, No.1, Rondo: Vivace Piano Abigail Yuan Beethoven - Sonata in C Minor Op. 10 No. 1 Piano Alex Liu Fritz Kreisler - Miniature Viennese Waltz Violin Cady Chen Chen Peixun – Autumn Moon Over the Calm Lake Piano 4PM Recital Jaylyn Chong Chopin-Nocturne No.20 in C sharp Minor Piano Allison Prakalapakorn Kabalevsky - Toccata, Op.60, No.4 from Four Rondos Piano Lahari Yallapragada Fritz Kreisler - Rondino on a Theme of Beethoven Violin Ethan Lee Debussy - La Plus Que Lente Piano Gareth Lee Franz Liszt - Liebestraum Nocturne No. -

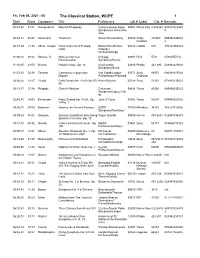

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Fri, Feb 05, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 31:51 Humperdinck Moorish Rhapsody Czecho-Slovak Radio 00509 Marco Polo 8.223369 489103023363 Symphony/Fischer-Die 0 skau 00:34:2102:08 Schumann Traumerei Alexis Weissenberg 07843 Virgin 234865 509992348652 Classics 2 00:37:2921:34 White, Joseph Violin Concerto in F sharp Barton Pine/Encore 04328 Cedille 035 735131903523 minor Chamber Orchestra/Hege 01:00:23 08:32 Strauss, R. Waltzes from Der Chicago 00458 RCA 5721 07863557212 Rosenkavalier Symphony/Reiner 01:10:0542:05 Berlioz Harold in Italy, Op. 16 Imai/London 02693 Philips 442 290 028944229028 Symphony/Davis 01:53:20 05:30 Thomas Connais-tu le pays from Von Stade/London 05873 Sony 89370 696998937024 Mignon Philharmonic/Pritchard Classical 02:00:2013:27 Vivaldi Cello Sonata No. 4 in B flat, RV Anner Bylsma 05188 Sony 51350 074645135021 45 02:15:17 27:48 Respighi Church Windows Cincinnati 08438 Telarc 80356 089408035623 Symphony/Lopez-Cob os 02:44:3514:08 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 9 in E, Op. John O'Conor 05592 Telarc 80293 089408029325 14 No. 1 03:00:1307:50 Balakirev Islamey, an Oriental Fantasy USSR 05750 Melodiya 34165 743213416526 Symphony/Svetlanov 03:09:0308:02 Debussy 3rd mvt (Andantino) from String Ysaye Quartet 09850 Decca 478 3691 028947836919 Quartet in G minor, Op. 10 03:18:1540:32 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. Ma/NY 03691 Sony 67173 074646717325 104 Philharmonic/Masur 04:00:1712:51 Alfven Swedish Rhapsody No. -

Max Bruch Symphonies 1–3 Overtures Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino

Max Bruch Symphonies 1–3 Overtures Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 1 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Max Bruch, 1870 cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 2 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Max Bruch (1838–1920) Complete Symphonies CD 1 Symphony No. 1 op. 28 in E flat major 38'04 1 Allegro maestoso 10'32 2 Intermezzo. Andante con moto 7'13 3 Scherzo. Presto 5'00 4 Quasi Fantasia. Grave 7'30 5 Finale. Allegro guerriero 7'49 Symphony No. 2 op. 36 in F minor 39'22 6 Allegro passionato, ma un poco maestoso 15'02 7 Adagio ma non troppo 13'32 8 Allegro molto tranquillo 10'57 T.T.: 77'30 cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 3 13.03.2020 10:56:27 CD 2 1 Prelude from Hermione op. 40 8'54 (Concert ending by Wolfgang Jacob) 2 Funeral march from Hermione op. 40 6'15 3 Entr’acte from Hermione op. 40 2'35 4 Overture from Loreley op. 16 4'53 5 Prelude from Odysseus op. 41 9'54 Symphony No. 3 op. 51 in E major 38'30 6 Andante sostenuto 13'04 7 Adagio ma non troppo 12'08 8 Scherzo 6'43 9 Finale 6'35 T.T.: 71'34 Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino, Conductor cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 4 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Bamberger Symphoniker (© Andreas Herzau) cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 5 13.03.2020 10:56:28 Auf Eselsbrücken nach Damaskus – oder: darüber, daß wir es bei dieser Krone der Schöpfung Der steinige Weg zu Bruch dem Symphoniker mit einem Kompositum zu tun haben, das sich als Geist mit mehr oder minder vorhandenem Verstand in einem In der dichtung – wie in aller kunst-betätigung – ist jeder Körper darstellt (die Bezeichnungen der Ingredienzien der noch von der sucht ergriffen ist etwas ›sagen‹ etwas ›wir- mögen wechseln, die Tatsache bleibt). -

Verdehr Trio Verdehr Trio

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 2-22-1991 Concert: Verdehr Trio Verdehr Trio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Verdehr Trio, "Concert: Verdehr Trio" (1991). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5582. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5582 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College ITHACA School of Music ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1990-91 VERDEHR TRIO Walter Verdehr, violin Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr, clarinet Gary Kirkpatrick, piano CREATURES OF PROMETHEUS, op. 43 Ludwig van Beethoven No. 14 Andante and Allegretto (1770-1827) EIGHT PIECES FOR CLARINET, VIOLA AND PIANO, op. 83 Max Bruch (1838-1920) transcribed by Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr VI. Nachtgesang: Andante con moto (Nocturn) IV. Allegro agitato A TRIO SETTING (19<JO) Gwither SchQller (b. 1925) Fast and Explosive Slow and Dreamy Allegretto; Scherzando e Leggiero IN1ERMISSION SONATA A TRE (1982) KarelHusa (b.1921) Con intensita Con sensitivita Con velocita SLAVONIC DANCES Antonin Dvofak (1841-1904) Tempo di Menuetto, op. 46, no. 2 Allegretto grazioso, op. 72, no. 2 Presto, op. 46, no. 8 Walter Ford Hall Auditorium Friday, February 22, 1991 8:15 p.m. PROGRAM NOTES Ludwig van Beethoven. Creatures of Prometheus, op. 43 The Andante and Allegretto, op. 43, no. 14 by Beethoven is taken from the ballet Creatures of Prometheus, op. 43. Written in 1800-1801, it was Beethoven's introduction to the Viennese stage and the first performance was given in the Burgtheater in Vienna on March 28, 1801. -

Masterpieces Celebrating the Human Journey Music by Barber, Bruch, Ravel, Prokofiev and Piazzolla

Masterpieces Celebrating the Human Journey Music by Barber, Bruch, Ravel, Prokofiev and Piazzolla Aude Castagna, Concert director and cello Vlada Volkova, piano; Jeff Gallagher, clarinet Shannon Delaney and Brian Johnston, violins Eleanor Angel, viola The Music Nostalgia: Prokofiev, Overture on Hebrew Themes (1919) Sergei Prokofiev wrote the Overture on Hebrew Themes, Op. 34, in 1919, during a trip to the United States. The piece was commissioned by a Russian sextet, the Zimro Ensemble, sponsored by the Russian Zionist Organization and was written for the unusual combination of clarinet, string quartet, and piano. The members had just arrived in America from the Far East on a world tour and gave Prokofiev a notebook of Jewish folksongs. The melodies Prokofiev chose have never been traced to any authentic sources and may have been actually composed by the ensemble’s clarinetist in the Jewish style. Its structure follows the form of a fairly conventional overture. It is in the key of C minor. The first theme, un poco allegro, has a jumpy and festive rhythm, unmistakably evoking klezmer music by alternating low and high registers and using repeated swelling and tapering of volume. The second theme, piu mosso, is a nostalgic cantabile theme introduced by the cello and then passed to the first violin. Dreams of Love: Eight Pieces for Clarinet, Cello, & Piano, (1910) Op. 83 by Max Bruch Numbers 1, 2,5, 6 and 7. Max Bruch (1838-1920) received his earliest music instruction from his mother, a noted singer and pianist. He was widely known and respected in his day as a composer, conductor, and teacher. -

Form, Style, and Influence in the Chamber Music of Antonin

FORM, STYLE, AND INFLUENCE IN THE CHAMBER MUSIC OF ANTONIN DVOŘÁK by MARK F. ROCKWOOD A DISSERTATION Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Mark F. Rockwood Title: Form, Style, and Influence in the Chamber Music of Antonin Dvořák This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Stephen Rodgers Chairperson Drew Nobile Core Member David Riley Core Member Forest Pyle Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Mark F. Rockwood This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial – Noderivs (United States) License. iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Mark F. Rockwood Doctor of Philosophy School of Music and Dance June 2017 Title: Form, Style, and Influence in the Chamber Music of Antonin Dvořák The last thirty years have seen a resurgence in the research of sonata form. One groundbreaking treatise in this renaissance is James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s 2006 monograph Elements of Sonata Theory : Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth- Century Sonata. Hepokoski and Darcy devise a set of norms in order to characterize typical happenings in a late 18 th -century sonata. Subsequently, many theorists have taken these norms (and their deformations) and extrapolate them to 19 th -century sonata forms. -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

Rep List 1.Pub

Richmond Symphony Orchestra League Student Concerto Competition Repertoire Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Guitar & percussion students are welcome to participate; Please contact Anne Hoffler, contest coordinator, at aahoffl[email protected] for repertoire approval no later than November 30. VIOLIN Faure Elegy, Op. 24 Bach All Violin concerti Haydn Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major Beethoven Violin Concerto in D major Haydn Cello Concerto No. 2 in D major Beethoven Romance No. 1 in G major Kabalevsky Cello Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 49 Beethoven Romance No. 2 in F major Lalo Cello Concerto in D minor Bériot Scéne de Ballet, Op. 100 Rubinstein Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op.96 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 7 in G major Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op.33 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 9 in A minor Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 119 Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor Schumann Cello Concerto in A minor Haydn All Violin concerti Shostakovich Concerto for Cello No. 1 Kabalevsky Violin Concerto in C Major, Op. 48 Stamitz All Cello concerti Lalo Symphonie Espagnole R. Strauss Romanze in F major Massenet Méditation from Thaïs Tchaikovsky Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op.33 Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 Vivaldi All Cello concerti Mozart Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat major Mozart Violin Concerto No. 2 in D major BASS Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major Bottesini Double Bass Concerto No.2 in B minor Mozart Violin Concerto No. -

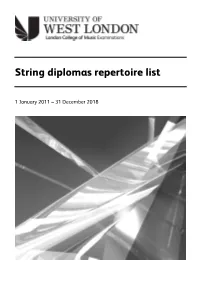

String Diplomas Repertoire List

String diplomas repertoire list 1 January 2011 – 31 December 2018 STRING DIPLOMAS 2011–2018 Contents Page LCM Publications ........................................................................................................................ 2 Overview of LCM Diploma Structure ................................................................................. 3 Violin DipLCM in Performance .......................................................................................................... 4 ALCM in Performance .............................................................................................................. 5 LLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 7 FLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 7 Viola DipLCM in Performance .......................................................................................................... 8 ALCM in Performance .............................................................................................................. 9 LLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 10 FLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 11 Cello DipLCM in Performance .........................................................................................................