A BOUNTY of BRAHMS Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Double Keyboard Concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

The double keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Waterman, Muriel Moore, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 18:28:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318085 THE DOUBLE KEYBOARD CONCERTOS OF CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH by Muriel Moore Waterman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: JAMES R. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

Brahms Schumann

BRAHMS Sonatas for Cello & Piano, Opp. 38 & 99 SCHUMANN Fünf Stücke im Volkston, Op. 102 ROBIN MICHAEL Cello DANIEL TONG Piano RES10188 Brahms & Schumann Works for Cello & Piano Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Sonata No. 1 for Cello and Piano in E minor, Op. 38 1. Allegro non troppo [13:26] 2. Allegretto quasi menuetto [5:37] Robin Michael cello 3. Allegro [6:23] Daniel Tong piano Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Fünf Stücke im Volkston, Op. 102 Cello by Stephan von Baehr (Paris, 2010), after Matteo Goffriller (1695) (Five Pieces in Folk Style) Bow by Noel Burke (Ireland, 2012), after François Xavier Tourte (1820) 4. Vanitas vanitatum [2:57] 5. Langsam [3:24] Blüthner Boudoir Grand Piano thought to have been played and 6. Nicht schnell, mit viel Ton zu spielen [3:56] selected by Brahms, Serial No. 45615 (1897) 7. Nicht zu rasch [1:54] 8. Stark und markiert [3:08] Johannes Brahms Sonata No. 2 for Cello and Piano in F major, Op. 99 9. Allegro vivace [8:51] 10. Adagio affettuoso [6:21] 11. Allegro passionato [6:51] 12. Allegro molto [4:41] About Robin Michael: Total playing time [67:35] ‘Michael played with fervour, graceful finesse and great sensitivity’ The Strad About Daniel Tong: ‘[...] it’s always a blessed relief to hear an artist with Daniel Tong’s self-evident love and understanding of the instrument’ BBC Music Magazine Brahms & Schumann: inventiveness and in its firm but delicately Works for Cello & Piano detailed structure.’ The first copies of the published sonata appeared in August 1866, Brahms started work on his Cello Sonata No. -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

Unc Symphony Orchestra Library

UNC ORCHESTRA LIBRARY HOLDINGS Anderson Fiddle-Faddle Anderson The Penny-Whistle Song Anderson Plink, Plank, Plunk! Anderson A Trumpeter’s Lullaby Arensky Silhouettes, Op. 23 Arensky Variations on a Theme by Tchaikovsky, Op. 35a Bach, J.C. Domine ad adjuvandum Bach, J.C. Laudate pueri Bach Cantata No. 106, “Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit” Bach Cantata No. 140, “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme” Bach Cantata No. 209, “Non sa che sia dolore” Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050 Bach Clavier Concerto No. 4 in A major, BWV 1055 Bach Clavier Concerto No. 7 in G minor, BWV 1058 Bach Concerto No. 1 in C minor for Two Claviers, BWV 1060 Bach Concerto No. 2 in C major for Three Claviers, BWV 1064 Bach Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, BWV 1041 Bach Concerto in D minor for Two Violins, BWV 1043 Bach Komm, süsser Tod Bach Magnificat in D major, BWV 243 Bach A Mighty Fortress Is Our God Bach O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross, BWV 622 Bach Prelude, Choral and Fugue Bach Suite No. 3 in D major, BWV 1068 Bach Suite in B minor Bach Adagio from Toccata, Adagio and Fugue in C major, BWV 564 Bach Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565 Barber Adagio for Strings, Op. -

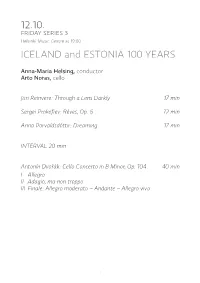

12.10. ICELAND and ESTONIA 100 YEARS

12.10. FRIDAY SERIES 3 Helsinki Music Centre at 19:00 ICELAND and ESTONIA 100 YEARS Anna-Maria Helsing, conductor Arto Noras, cello Jüri Reinvere: Through a Lens Darkly 17 min Sergei Prokofiev: Rêves, Op. 6 12 min Anna Þorvaldsdóttir: Dreaming 17 min INTERVAL 20 min Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 40 min I Allegro II Adagio, ma non troppo III Finale: Allegro moderato – Andante – Allegro vivo 1 The LATE-NIGHT CHAMBER MUSIC will begin in the main Concert Hall after an interval of about 10 minutes. Those attending are asked to take (unnumbered) seats in the stalls. Paula Sundqvist, violin Tuija Rantamäki, cello Sonja Fräki, piano Antonín Dvořák: Piano Trio “Dumky” 31 min 1. Lento maestoso – Allegro vivace – Allegro molto 2. Poco adagio – Vivace 3. Andante – Vivace non troppo 4. Andante moderato – Allegretto scherzando – Allegro 5. Allegro 6. Lento maestoso – Vivace Interval at about 20:00. The concert will end at about 21:15, the late-night chamber music at about 22:00. Broadcast live on Yle Radio 1 and Yle Areena. It will also be shown in two parts in the programme “RSO Musiikkitalossa” (The FRSO at the Helsinki Music Centre) on Yle Teema on 21.10. and 4.11., with a repeat on Yle TV 1 on 27.10. and 10.11. 2 JÜRI REINVERE director became a close friend and im- portant mentor of the young compos- (b. 1971): THROUGH A er. Theirs was not simply a master-ap- LENS DARKLY prenticeship relationship, for they often talked about music, and Reinvere would Jüri Reinvere has been described as a sometimes express his own views as a true cosmopolitan with Estonian roots. -

Nuveen Investments Emerging Artist Violinist Julia Fischer Joins the Cso and Riccardo Muti for June Subscription Concerts at Symphony Center

For Immediate Release: Press Contacts: June 13, 2016 Eileen Chambers, 312-294-3092 Photos Available By Request [email protected] NUVEEN INVESTMENTS EMERGING ARTIST VIOLINIST JULIA FISCHER JOINS THE CSO AND RICCARDO MUTI FOR JUNE SUBSCRIPTION CONCERTS AT SYMPHONY CENTER June 16 – 21, 2016 CHICAGO—Internationally acclaimed violinist Julia Fischer returns to Symphony Center for subscription concerts with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) led by Music Director Riccardo Muti on Thursday, June 16, at 8 p.m., Friday, June 17, at 1:30 p.m., Saturday, June 18, at 8 p.m., and Tuesday, June 21, at 7:30 p.m. The program features Brahms’ Serenade No. 1 and Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major with Fischer as soloist. Fischer’s CSO appearances in June are endowed in part by the Nuveen Investments Emerging Artist Fund, which is committed to nurturing the next generation of great classical music artists. Julia Fischer joins Muti and the CSO for Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. Widely recognized as the first “Romantic” concerto, Beethoven’s lush and virtuosic writing in the work opened the traditional form to new possibilities for the composers who would follow him. The second half of the program features Brahms’ Serenade No. 1. Originally composed as chamber music, Brahms later adapted the work for full orchestra, offering a preview of the rich compositional style that would emerge in his four symphonies. The six-movement serenade is filled with lyrical wind and string passages, as well as exuberant writing in the allegro and scherzo movements. German violinist Julia Fischer won the Yehudi Menuhin International Violin Competition at just 11, launching her career as a solo and orchestral violinist. -

PROGRAM NOTES: “Violin Concerto”

PROGRAM NOTES: “Violin Concerto” I believe that one of the most rewarding aspects of life is exploring and discovering the magic and mysteries held within our universe. For a composer this thrill often takes place in the writing of a concerto…it is the exploration of an instrument’s world, a journey of the imagination, confronting and stretching an instrument’s limits, and discovering a particular performer’s gifts. The first movement of this concerto, written for the violinist, Hilary Hahn, carries a somewhat enigmatic title of “1726”. This number represents an important aspect of such a journey of discovery, for both the composer and the soloist. 1726 happens to be the street address of The Curtis Institute of Music, where I first met Hilary as a student in my 20th Century Music Class. An exceptional student, Hilary devoured the information in the class and was always open to exploring and discovering new musical languages and styles. As Curtis was also a primary training ground for me as a young composer, it seemed an appropriate tribute. To tie into this title, I make extensive use the intervals of unisons, 7ths, and 2nds, throughout this movement. The excitement of the first movement’s intensity certainly deserves the calm and pensive relaxation of the 2nd movement. This title, “Chaconni”, comes from the word “chaconne”. A chaconne is a chord progression that repeats throughout a section of music. In this particular case, there are several chaconnes, which create the stage for a dialog between the soloist and various members of the orchestra. The beauty of the violin’s tone and the artist’s gifts are on display here. -

Double Bass Sound Christine Hoock

MOZARTEUM DOUBLE BASS SOUND CHRISTINE HOOCK RECORDS MOZARTEUM DOUBLE BASS SOUND – Christine Hoock Die CD-Reihe „Mozarteum-Sound“ hat es sich ten und Studierenden ihrer Klasse im Fokus dieser zum Ziel gesetzt, hervorragende künstlerische Aufnahme. Als Partner standen ihr bei der Reali- Leistungen wie auch eine besondere Klangästhetik sierung dieses breitgefächerten Repertoires Hans- – immer in Bezug auf ein bestimmtes Instrument jörg Angerer (Chefdirigent der Bläserphilharmonie – an der Universität Mozarteum Salzburg zu do- Mozarteum Salzburg), Benjamin Schmid (Violine), kumentieren. Mari Kato (Klavier), Ariane Haering (Klavier), Bar- bara Nussbaum (Klavier) und DJ UmbertoEcho (Mi- Diesmal dem Kontrabass mit seiner außerordent- xing Desk) zur Seite. lichen Beweglichkeit, seinem Farbenreichtum und seiner Virtuosität – dabei oft nahezu archaische Klangwelten erschaffend – gewidmet, steht die au- ßergewöhnliche Kontrabass-Künstlerin Christine Hoock gemeinsam mit Absolventinnen/Absolven- MOZARTEUM DOUBLE BASS SOUND – Christine Hoock The CD series Mozarteum Sound aims to docu- the Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg), ment excellent artistic achievements at the Moz- Benjamin Schmid (violin), Mari Kato (piano), Ariane arteum University as well as a particular kind of Haering (piano), Barbara Nussbaum (piano) and aesthetic sound, always related to a certain in- DJ UmbertoEcho (mixing desk). strument. This recording is devoted to the double bass and reveals its extraordinary fl exibility, rich colours and virtuosity, and features the outstanding double bass player Christine Hoock, together with graduates and students from her class. Partners in the realization of this broad repertoire were Hansjörg Angerer (principal conductor of 1 1 CHRISTINE HOOCK „... jeder entscheidet sich intuitiv für das Instru- Dies spiegelt sich auch in ihrer abwechslungsrei- Die Preisträgerin internationaler Wettbewerbe ar- Christine Hoock leitet die Internationale Johann- ment, dessen Tonhöhe und Klangfarbe seine innere chen Diskographie wieder. -

Performances from 1974 to 2020

Performances from 1974 to 2020 2019-20 December 1 & 2, 2018 Michael Slon, Conductor September 28 & 29, 2019 Family Holiday Concerts Benjamin Rous, Conductor MOZART Symphony No. 32 February 16 & 17, 2019 ROUSTOM Ramal Benjamin Rous, Conductor BRAHMS Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major RAVEL Pavane pour une infante défunte RAVEL Piano Concerto in G Major November 16 & 17, 2019 MOYA Siempre Lunes, Siempre Marzo Benjamin Rous & Michael Slon, Conductors KODALY Variations on a HunGarian FolksonG MONTGOMERY Caught by the Wind ‘The Peacock’ RICHARD STRAUSS Horn Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major March 23 & 24, 2019 MENDELSSOHN Psalm 42 Benjamin Rous, Conductor BRUCKNER Te Deum in C Major BARTOK Violin Concerto No. 2 MENDELSSOHN Symphony No. 4 in A Major December 6 & 7, 2019 Michael Slon, Conductor April 27 & 28, 2019 Family Holiday Concerts Benjamin Rous, Conductor WAGNER Prelude from Parsifal February 15 & 16, 2020 SCHUMANN Piano Concerto in A minor Benjamin Rous, Conductor SHATIN PipinG the Earth BUTTERWORTH A Shropshire Lad RESPIGHI Pines of Rome BRITTEN Nocturne GRACE WILLIAMS Elegy for String Orchestra June 1, 2019 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS On Wenlock Edge Benjamin Rous, Conductor ARNOLD Tam o’Shanter Overture Pops at the Paramount 2018-19 2017-18 September 29 & 30, 2018 September 23 & 24, 2017 Benjamin Rous, Conductor Benjamin Rous, Conductor BOWEN Concerto in C minor for Viola WALKER Lyric for StrinGs and Orchestra ADAMS Short Ride in a Fast Machine MUSGRAVE SonG of the Enchanter MOZART Clarinet Concerto in A Major SIBELIUS Symphony No. 2 in D Major BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A Major November 17 & 18, 2018 October 6, 2017 Damon Gupton, Conductor Michael Slon, Conductor ROSSINI Overture to Semiramide UVA Bicentennial Celebration BARBER Violin Concerto WALKER Lyric for StrinGs TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. -

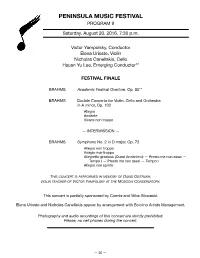

Program Notes by Dr

PENINSULA MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAM 9 Saturday, August 20, 2016, 7:30 p.m. Victor Yampolsky, Conductor Elena Urioste, Violin Nicholas Canellakis, Cello Hsuan Yu Lee, Emerging Conductor** FESTIVAL FINALE BRAHMS Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80** BRAHMS Double Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 102 Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo — INTERMISSION — BRAHMS Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso (Quasi Andantino) — Presto ma non assai — Tempo I — Presto ma non assai — Tempo I Allegro con spirito THIS CONCERT IS PERFORMED IN MEMORY OF DAVID OISTRAKH, VIOLIN TEACHER OF VICTOR YAMPOLSKY AT THE MOSCOW CONSERVATORY. This concert is partially sponsored by Connie and Mike Glowacki. Elena Urioste and Nicholas Canellakis appear by arrangement with Sciolino Artists Management. Photography and audio recordings of this concert are strictly prohibited. Please, no cell phones during the concert. — 30 — PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA Double Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra in A Program 9 minor, Op. 102 JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) Composed in 1887. Premiered on October 18, 1887 in Cologne, with Joseph Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 Joachim and Robert Hausmann as soloists and the com- poser conducting. Composed in 1880. Premiered on January 4, 1881 in Breslau, conducted by Johannes Brahms first met the violinist Joseph the composer. Joachim in 1853. They became close friends and musi- cal allies — the Violin Concerto was not only written Artis musicae severioris in Germania nunc princeps for Joachim in 1878 but also benefited from his careful — “Now the leader in Germany of music of the more advice in many matters of string technique. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito.