(Of(R) Viola) and Piano Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Preview Notes • Week Two • Persons Auditorium

2019 Preview Notes • Week Two • Persons Auditorium Saturday, July 20 at 8:00pm Flute Quartet in D Major, K. 285 (1777-78) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Born January 27, 1756 • Died December 5, 1791 Duration: approx. 15 minutes Last Marlboro performance: 2011 When Mozart was just a few years younger than the junior participants in this group, he travelled throughout Europe with his mother in search of employment. While in Mannheim on his way to Paris, he met a Dutch merchant named Willem van Britten Dejong who happened to be an amateur flute player. Dejong, who had made his fortune in India, was happy to commission three concertos and three quartets for his instrument. Mozart, who needed the funds, was happy to accept. However, he only completed the quartets and two concertos (one a transcription of a previously-composed oboe concerto) by the time he left Mannheim. What he did write, though, charmingly showcases the flute. In this quartet, that instrument takes the lead throughout a buoyant Allegro beginning, a delicate Adagio accompanied by sparkling plucking from the strings, and a boisterous but well-balanced Rondo conclusion. Participants: Giorgio Consolati, flute; Hiroko Yajima, violin; Jordan Bak, viola; Alexander Hersh, cello Octet (2004) Jörg Widmann Born June 19, 1973 • In residence 2008, 2019 Duration: approx. 30 minutes Marlboro Premiere Though Widmann’s Octet features frequent microtones, he admits that the piece is “almost throughout, a tonal piece,” which was “risky to write in 2004.” The instrumentation suggests a clear connection to Schubert’s genre-making octet, and the piece’s central third movement, which is titled Lied ohne Worte, is a plangent nod to the composer who wrote so many Lieder over the course of his short life. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

Vorwort Der Ihm Eigenen Selbstironie – Das Ma Folgenden Johannes Brahms

Vorwort der ihm eigenen Selbstironie – das Ma Folgenden Johannes Brahms. Briefwech- nuskript des ganzen Werks als „Probe“ sel, Bd. XII, hrsg. von Max Kalbeck, Ber bezeichnete und es komplett an Mandy lin 1919, Reprint Tutzing 1974, S. 47 ff.). czewski schickte. Dieser begann mit der Nach der Berliner Uraufführung über Zwar hatte Johannes Brahms (1833 – 97) Partiturabschrift des Quintetts, vermut sandte er ihm am 24. Dezember 1891 im Dezember 1890 seinem Verleger Fritz lich weil Brahms’ damaliger Hauptko zunächst die Partiturabschrift des Quin Simrock angekündigt, mit dem Kompo pist William Kupfer zu dieser Zeit noch tetts als Vorlage für ein geplantes Ar nieren aufhören zu wollen, aber schon mit der Abschrift des Klarinettentrios rangement für Klavier zu vier Händen. bald sollte er nochmals tätig werden. Ein befasst war. Nach Abschluss von Satz I Kurz nach der zweiten Aufführung des wichtiger Impuls dafür ging von dem durch Mandyczewski setzte Kupfer die Klarinettenquintetts in Wien gingen am Klarinettisten der Meininger Hofkapelle Abschrift fort und kopierte die Stim 23. Januar dann auch die abschriftlichen Richard Mühlfeld aus, den Brahms im men, vermutlich schrieb er auch die al Stimmen an Simrock zur Vorbereitung Frühjahr 1891 näher kennen und sehr ternative Solopartie für Viola aus. Wann des Stichs. Vermutlich im Februar 1892 schätzen lernte. Begeistert schwärmte die abschriftlichen Materialien fertigge las der Komponist Druckfahnen von er am 17. März in einem Brief an Clara stellt waren, kann nicht genau festge Partitur und Stimmen Korrektur, denn Schumann, man könne „nicht schöner stellt werden. Spätestens zu den ersten am 25. Februar beklagte er sich brief Klarinette blasen, als es der hiesige Herr Proben der beiden neuen Stücke mit Ri lich darüber, dass die Stimmen bereits Mühlfeld tut“. -

JOHANNES BRAHMS: CLASSICAL INCLINATIONS in a ROMANTIC AGE a Series of Fourteen Recitals with Pianist Ian Hobson and Colleagues

JOHANNES BRAHMS: CLASSICAL INCLINATIONS IN A ROMANTIC AGE A series of fourteen recitals with pianist Ian Hobson and colleagues 1. Tuesday, September 10, 2013, 7:30 p.m., Benzaquen Hall Brahms: Scherzo in E flat minor, Op. 4 Ian Hobson, piano Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Op. 23 for piano four hands Ian Hobson, piano, Claude Hobson, piano ----------- Brahms : Piano Sonata No. 1 in C major, Op. 1 Ian Hobson, piano 2. Thursday, September 12, 2013, 7:30 p.m., Benzaquen Hall Brahms: Piano Sonata No. 2 in F sharp minor, Op. 2 Ian Hobson, piano Hungarian Dances, Book 1: Nos. 1 – 5 arranged for solo piano Ian Hobson, piano ----------- Brahms: Hungarian Dances, Book 2: Nos. 6 – 10 arranged for solo piano Ian Hobson, piano Hungarian Dances, Book 3-4: Nos. 11 – 21 for piano four hands Ian Hobson, piano, Edward Rath, piano 3. Tuesday, September 24, 2013, 7:30 p.m.,Benzaquen Hall J.S.Bach/Brahms: Chaconne in D minor arranged for piano left hand Ian Hobson, piano Brahms: Zigeunerlieder, Op. 103, arranged by Theodor Kirchner for piano four hands Ian Hobson, piano, Samir Golescu, piano ---------- Brahms : Theme and Variations in D minor arranged for piano from the B flat sextet for strings, Op. 18 Ian Hobson, piano J.S.Bach/Brahms: Presto in G minor arranged for piano (two versions) Ian Hobson, piano Brahms: Six Baroque Movements Ian Hobson, piano Brahms: Three Little Pieces Ian Hobson, piano Brahms: Five Arrangements Ian Hobson, piano 4. Thursday, September 26, 2013, 7 :30 p.m., Cary Hall Brahms: Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Op. -

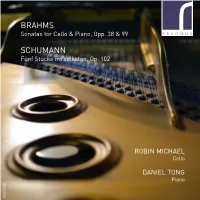

Brahms Schumann

BRAHMS Sonatas for Cello & Piano, Opp. 38 & 99 SCHUMANN Fünf Stücke im Volkston, Op. 102 ROBIN MICHAEL Cello DANIEL TONG Piano RES10188 Brahms & Schumann Works for Cello & Piano Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Sonata No. 1 for Cello and Piano in E minor, Op. 38 1. Allegro non troppo [13:26] 2. Allegretto quasi menuetto [5:37] Robin Michael cello 3. Allegro [6:23] Daniel Tong piano Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Fünf Stücke im Volkston, Op. 102 Cello by Stephan von Baehr (Paris, 2010), after Matteo Goffriller (1695) (Five Pieces in Folk Style) Bow by Noel Burke (Ireland, 2012), after François Xavier Tourte (1820) 4. Vanitas vanitatum [2:57] 5. Langsam [3:24] Blüthner Boudoir Grand Piano thought to have been played and 6. Nicht schnell, mit viel Ton zu spielen [3:56] selected by Brahms, Serial No. 45615 (1897) 7. Nicht zu rasch [1:54] 8. Stark und markiert [3:08] Johannes Brahms Sonata No. 2 for Cello and Piano in F major, Op. 99 9. Allegro vivace [8:51] 10. Adagio affettuoso [6:21] 11. Allegro passionato [6:51] 12. Allegro molto [4:41] About Robin Michael: Total playing time [67:35] ‘Michael played with fervour, graceful finesse and great sensitivity’ The Strad About Daniel Tong: ‘[...] it’s always a blessed relief to hear an artist with Daniel Tong’s self-evident love and understanding of the instrument’ BBC Music Magazine Brahms & Schumann: inventiveness and in its firm but delicately Works for Cello & Piano detailed structure.’ The first copies of the published sonata appeared in August 1866, Brahms started work on his Cello Sonata No. -

A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’S Clarinet Sonata

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata Kenneth T. Aoki Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Composition Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation Aoki, Kenneth T., "A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1077. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1077 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SONATA WITH AN ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF A BRAHMS' AND HINDEMITH'S CLARINET SONATA A Covering Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Education by Kenneth T. Aoki August, 1968 :N01!83 i iuJ :JV133dS q g re. 'H/ £"Ille; arr THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC CENTRAL WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGE presents in KENNETH T. AOKI, Clarinet MRS. PATRICIA SMITH, Accompanist PROGRAM Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in B flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2. J. Brahms Allegro amabile Allegro appassionato Andante con moto II Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano .............................................. 8. Heiden Con moto Andante Vivace, ma non troppo Caprice for B flat Clarinet ................................................... -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Brahms Clarinet Quintet & Trio 6 Songs

martin fröst brahms clarinet quintet & trio 6 songs janine jansen boris brovtsyn maxim rysanov torleif thedéen boris brovtsyn | martin fröst | janine jansen | maxim rysanov | torleif thedéen roland pöntinen BIS-2063 BIS-2063_f-b.indd 1 2014-02-24 14.39 BRAHMS, Johannes (1833–97) Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115 37'46 1 I. Allegro 12'37 2 II. Adagio – Più lento 11'08 3 III. Andantino – Presto non assai, ma con sentimento 4'34 4 IV. Con moto 9'05 Janine Jansen & Boris Brovtsyn violins Maxim Rysanov viola · Torleif Thedéen cello Six Songs, transcribed by Martin Fröst for clarinet and piano 5 Die Mainacht, Op. 43 No. 2 3'32 6 Mädchenlied, Op. 107 No. 5 1'31 7 Immer leiser wird mein Schlummer, Op. 105 No. 2 3'12 8 Wie Melodien zieht es mir, Op. 105 No. 1 2'09 9 Vergebliches Ständchen, Op. 84 No. 4 1'31 10 Feldeinsamkeit, Op. 86 No. 2 3'22 Roland Pöntinen piano 2 Trio in A minor for Clarinet, Piano and Cello 24'33 Op. 114 11 I. Allegro 7'48 12 II. Adagio 7'39 13 III. Andantino grazioso 4'24 14 IV. Allegro 4'25 Roland Pöntinen piano · Torleif Thedéen cello TT: 78'55 Martin Fröst clarinet 3 n the same way that the world owes Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto, Trio and Quintet to the virtuosity of Anton Stadler, and Weber’s clarinet works to IHeinrich Baermann, so the creation of Brahms’s last four chamber works was sparked by the artistry of Richard Mühlfeld (1856–1907), the principal clarinettist of the Meiningen Orchestra. -

September 2019 Catalogue Issue 41 Prices Valid Until Friday 25 October 2019 Unless Stated Otherwise

September 2019 Catalogue Issue 41 Prices valid until Friday 25 October 2019 unless stated otherwise ‘The lover with the rose in his hand’ from Le Roman de la 0115 982 7500 Rose (French School, c.1480), used as the cover for The Orlando Consort’s new recording of music by Machaut, entitled ‘The single rose’ (Hyperion CDA 68277). [email protected] Your Account Number: {MM:Account Number} {MM:Postcode} {MM:Address5} {MM:Address4} {MM:Address3} {MM:Address2} {MM:Address1} {MM:Name} 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, As summer gives way to autumn (for those of us in the northern hemisphere at least), the record labels start rolling out their big guns in the run-up to the festive season. This year is no exception, with some notable high-profile issues: the complete Tchaikovsky Project from the Czech Philharmonic under Semyon Bychkov, and Richard Strauss tone poems from Chailly in Lucerne (both on Decca); the Beethoven Piano Concertos from Jan Lisiecki, and Mozart Piano Trios from Barenboim (both on DG). The independent labels, too, have some particularly strong releases this month, with Chandos discs including Bartók's Bluebeard’s Castle from Edward Gardner in Bergen, and the keenly awaited second volume of British tone poems under Rumon Gamba. Meanwhile Hyperion bring out another volume (no.79!) of their Romantic Piano Concerto series, more Machaut from the wonderful Orlando Consort (see our cover picture), and Brahms songs from soprano Harriet Burns. Another Hyperion Brahms release features as our 'Disc of the Month': the Violin Sonatas in a superb new recording from star team Alina Ibragimova and Cédric Tiberghien (see below). -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

Program Notes Quartet No

Ariel Quartet Gershon Gerchikov, violin Alexandra Kazovsky, violin Jan Grüning, viola Amit Even-Tov, cello with Ilya Shterenberg, clarinet Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110 Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-75) Largo Allegro molto Allegretto Largo Largo Clarinet Quintet in A major, K. 581 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91) Allegro Larghetto Menuetto Allegretto con variazioni Clarinet Quintet in B-Flat Major, Op. 34 Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) Rondo: Allegro giojoso - INTERMISSION - Quartet in D minor, D. 810, “Death and the Maiden” Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Allegro Andante con moto Scherzo. Allegro molto Presto Ariel Quartet is represented by MKI Artists; One Lawson Lane, Suite 320, Burlington, VT 05401. Recordings: Avie Records www.arielquartet.com www.sacms.org Program Notes Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110 Dmitri Shostakovich By 1960 the ‘Thaw’ following Stalin’s death had improved the outward circumstances of Shostakovich’s life, and he was honored at home and allowed to travel abroad to perform and receive additional honors. The price was a requirement that he perform many duties for the official music establishment. In April 1960, at the personal invitation of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, Shostakovich was elected head of the Russian Composers’ Union. He was also pressured to join the Communist Party, a step he had avoided during all his earlier years of torment. he did this without telling his family and friends, and when it became public the intense shame of his capitulation led to a nervous breakdown in June 1960. “I’ve been a whore, I am and always will be a whore,” he told his old friend Isaak Glikman with tears streaming down his face. -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 Johannes Brahms ohannes Brahms was 29 years old in 1862, seated at the other piano. Ironically, critics Jwhen he embarked on this seminal mas- now complained that the work lacked the terpiece of the chamber-music repertoire, sort of warmth that string instruments would though the work would not reach its final have provided — the opposite of Joachim’s form as his Piano Quintet until two years objection. Unlike the original string-quintet later. He was no beginner in chamber music version, which Brahms burned, the piano when he began this project. He had already duet was published — and is still performed written dozens of ensemble works before and appreciated — as his Op. 34bis. he dared to publish one, his B-major Piano By this time, however, Brahms must have Trio (Op. 8) of 1853–54. Among those early, grown convinced of the musical merits of his unpublished chamber pieces were 20-odd material and, with some coaxing from his string quartets, all of which he consigned friend Clara Schumann, he gave the piece to destruction prior to finally publishing his one more try, incorporating the most idiom- three mature works in that classic genre in atic aspects of both versions. The resulting the 1870s. In truth, he did get some use out Piano Quintet, the composer’s only essay of those early quartets — to paper the walls in that genre (and no wonder, after all that and ceilings of his apartment.