Michael Berkeley and David Malouf's Rewriting of Jane Eyre: an Operatic and Literary Palimpsest*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wide Sargasso Sea

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING ENGLISH: ANXIETY OF ENGLISHNESS IN CHARLOTTE BRONTË’S JANE EYRE AND JEAN RHYS’S WIDE SARGASSO SEA By Sarah Whittemore Bachelor of Arts, September 2004 May 2008, The George Washington University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English May 18, 2008 Thesis directed by Tara Wallace Associate Professor of English The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Sarah Whittemore has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English as of May 12, 2008. This is the final and approved form of the thesis. THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING ENGLISH: ANXIETY OF ENGLISHNESS IN CHARLOTTE BRONTË’S JANE EYRE AND JEAN RHYS’S WIDE SARGASSO SEA Sarah Whittemore Thesis Research Committee: Tara Wallace, Associate Professor of English, Director Antonio Lopez, Assistant Professor of English, Reader ii © Copyright 2008 by Sarah Whittemore All rights reserved iii Acknowledgments I would like to start by acknowledging all of those who played a major role in helping me to successfully complete this project. First and foremost, I would like to thank my family who provided not only the inspiration for my thesis topic, but the constant love and support necessary to carry it out. A special thanks to Matt for keeping me motivated (and caffeinated) throughout the semester and to my three amazing roommates for constantly believing in me. Finally, I would like to thank the GW English department, specifically Tara Wallace and Gil Harris for their patience and guidance throughout the year. -

Download the Job Description

MUSIC. THEATRE. WALES. needs a Marketing and Communications Manager Fixed term contract until the end of December 2020 (part-time) We are inviting applications from suitably qualified candidates who are able to offer 3 days a week. The company is based in an attractive, modern office situated within a listed building close to Cardiff Bay station and the successful candidate will be expected to work from here. Salary: £27-30k depending on experience (pro rata) Music Theatre Wales is one of Europe’s leading contemporary opera companies, recognised since its formation in 1988 as a vital force in opera, presenting bold new work that is characterised by the powerful impact it makes on audiences and artists alike. We work in association with the UK’s leading contemporary music ensemble, the London Sinfonietta, with whom all our productions are performed. In 2020, we will deliver two contrasting new works: February/March 2020 • Denis & Katya by Philip Venables and Ted Huffman has already proved to be an outstanding success with our co-producers at Opera Philadelphia where the work has been acclaimed as a totally new way of using opera and music theatre to engage with current social issues. Alongside this, we will run a Young People’s Consultation and Creative Project aimed at hard-to-reach young people in Newport and Mold. June/July and Autumn 2020 • Violet will be an equally powerful contemporary work which presents a female- centred plot that stands in stark contrast to most of the operatic canon. Composed by Tom Coult and written by Alice Birch – an outstanding and uncompromising theatre writer known for her strong females leads – Violet will give award-winning theatre director Rebecca Frecknall the chance to work in opera for the first time. -

Year 9 English Distance Learning Quiz and Learn Booklet Summer 2

Name: Year 9 English Distance Learning Quiz and Learn Booklet Summer 2 Name : Form : Week 1: Jane Eyre – Plot This week you will be recapping the plot of Jane Eyre – the first text you studied in Year 9. How much can you remember? This book is full of interesting themes and ideas that will also help you with the new texts that you will be reading in Year 10! Jane Eyre is a first-person narrative told from the perspective of Jane, a seemingly ‘plain’ girl who meets a lot of challenges in life. The novel presents Jane’s life from childhood to adulthood. Jane Eyre is a novel written by Charlotte Brontë in 1847. The novel follows the story of Jane, a seemingly plain and simple girl as she battles through life's struggles. Jane has many obstacles in her life - her cruel and abusive Aunt Reed, the grim conditions at Lowood school, her love for Rochester and Rochester's marriage to Bertha. However, Jane overcomes these obstacles through her determination, sharp wit and courage. The novel ends with Jane married to Rochester with children of their own. There are elements of Jane Eyre that echo Charlotte Brontë's own life. She and her sisters went to a school run by a headmaster as severe as Mr Brocklehurst. Two of Charlotte's sisters died there from tuberculosis (just like Jane's only friend, Helen Burns). Charlotte Brontë was also a governess for some years before turning to writing. Jane Eyre – Short Plot Summary 1. The novel begins with Jane living at her aunt's, Mrs Reed. -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte Janes Journey Through Life

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte Janes journey through life. Maria Thuresson Autumn 2011 Section for Learning and Environment Kristianstad University Jane Mattisson Maria Thuresson 1 Abstract The aim of this essay is to examine Janes personal progress through the novel Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte. It addresses the issue of personal development in relation to social position in England during the nineteenth – century. The essay follows Janes personal journey and quest for independence, equality, self worth and love from a Marxist perspective. In the essay close- reading is also applied as a complementary theory. Keywords: Jane Eyre, Charlotte Bronte, personal progress, nineteenth-century. Maria Thuresson 2 ”(…) Two roads diverged in a wood, and I – I took the one less travelled by, and that had made all the difference.” (Robert Frost, www.poets.org ) Life is like a walk on a road that sometimes turns and takes you places that you never imagined, this is what Charlotte Brontes novel Jane Eyre is about, a journey through life. The essay argues that Jane Eyre progresses throughout the novel, from the perspective of personal development and personal integrity in response to the pressures and expectations of the nineteenth- century social class system. It also argues that Jane’s progress is a circular journey in the sense that she begins her journey in the same social class as she ends up. The essay will examine Jane’s personal journey in the context of five major episodes in the novel. In the five episodes the names of the places are metaphors for stages in Jane’s personal journey. -

Operational Plan This Year Reflects an Important Moment of Change

Foreword from the Chair and Chief Executive of the Arts Council of Wales These are challenging times for the publicly funded arts in Wales. This isn’t because people don’t care about them – the public are enjoying and taking part in the arts in large numbers. It isn’t because the work is poor – critical acclaim and international distinction tells us differently. The arts remain vulnerable because continuing economic pressures are forcing uncomfortable choices about which areas of civic life can argue the most persuasive case for support. Fortunately, the Welsh Government recognises and understands the value of arts and creativity. Even in these difficult times, the Government is increasing its funding to the Arts Council in 2017/18 by 3.5%. This vote of confidence in Wales’ artists and arts organisations is as welcome as it’s deserved. But economic austerity continues and this increases our responsibility to ensure that the benefits that the arts offer are available to all. If we want Wales to be fair, prosperous and confident, improving the quality of life of its people in all of the country’s communities, then we must make the choices that enable this to happen – hard choices that will require us to be clear about our priorities. We intend over the coming years to make some important changes – not recklessly or heedlessly, but because we feel that we must try harder to ensure that the benefits of the arts are available more fairly across Wales. It is time to tackle the lack of engagement, amongst those not traditionally able to take part in the arts and in those places where the chance to enjoy the arts is more limited. -

Jane Eyre and Wide Sargasso Sea

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Zuzana Violová A Comparative Analysis of Jane Eyre and Wide Sargasso Sea Supervisor: prof. Mgr. Milada Franková, CSc., M.A. 2017 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature 2 Acknowledgment I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, prof. Mgr. Milada Franková, CSc., M.A., for her guidance, support and valuable advice. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………........ 5 2. Literary Context ……………………………………………………………………. 8 2.1. Charlotte Brontë and Jane Eyre ……………………………………………………….. 9 2.2. Jean Rhys and Wide Sargasso Sea ……...…………………………………………….. 13 3. Analysis of Jane Eyre ……………………………………………………………... 17 3.1. Jane’s Path to Womanhood …………………………………………………………... 18 3.2. Jane Eyre, the Heroin ………………………………………………………………… 22 4. Analysis of Wide Sargasso Sea …………………………………………………… 29 4.1. Antoinette’s Path to Womanhood ……………………………………………………. 30 4.2. From Antoinette to Bertha……………………………………………………………. 33 5. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………… 37 Works Cited …………………………………………………….................................... 41 Resumé (English) ……………………………………………………………………... 43 Resumé (Czech) ………………………………………………………………………. 44 4 1. Introduction Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea are novels that are based on significant female characters who are exposed to strong male dominance. Jane Eyre, a highly praised novel of the Victorian era published in 1847, unfolds a story of an orphaned girl’s journey from childhood to maturity, whose immense persistence and patience had made her one of the most remarkable literary characters known to this day. On top of that, Brontë’s intriguing writing immediately draws its readers in and the popularity the novel has been still gaining to this day is earned rightfully. -

Michael Berkeley Selected Reviews

Michael Berkeley Selected Reviews Winter Fragments (Chamber Music Recording) Resonus Classics RES10223 (September 2018) “Stylistically ranging from the plainchant-inspired Clarinet Quintet (1983) to the sensuous and Satie-like Seven (2007), to the jostling intensity of Catch Me If You Can (1994), it shows Berkeley at his exploratory and individualistic best, free to follow his instinct, tonal or expressionistic” – Fiona Maddocks, The Guardian “Even when working with large-scale forces such as opera and music theatre, Michael Berkeley's style and expression remain attuned to the more intimate nuances of chamber music. Perhaps this is because the chamber context provides such an effective vehicle for one of his music's most distinctive features - the often dichotomous interplay between the individual and the group... the Berkeley Ensemble, directed by Dominic Grier, are excellent throughout - entirely at one with the music of their namesake composer” – Pwyll ap Sion, Gramophone “There’s contrast aplenty – Catch Me If You Can (1994) a feisty, frenetic triptych, the gentle, self-echoing, harp-centred Seven (2007) pregnant with a pensiveness that collides late Mahler with Satie at his most subdued. The Clarinet Quintet (1983) is spun from sinewy, twisting strands contrasting the playful impetuosity and dark-hued luminosity of John Slack’s clarinet to end in a moment of sublimely subdued beauty. 2010’s Rilke-setting Sonnet for Orpheus and the seven-part song-cycle Winter Fragments (1996) – both benefiting from Fleur Barron’s ardent mezzo – -

Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Villette, and the Tenant of Wildfell Hall

‘The Madman out of The Attic’ Gendered Madness in Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Villette, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Bury, Hannah Citation Bury, H, J. (2019). ‘The Madman out of The Attic’ Gendered Madness in Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Villette, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (Masters dissertation). University of Chester, UK. Publisher University of Chester Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 01/10/2021 16:20:51 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/623103 University of Chester Department of English MA Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture EN7204 Dissertation 2018-19 ‘The Madman out of The Attic’ Gendered Madness in Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Villette, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Hannah Jayne Bury 1 Abstract The nineteenth-century ‘madwoman’ is critically established, but not always contentiously questioned or repudiated, within Brontë scholarship. This dissertation will therefore explore the possibility that the quintessentially ‘mad’ female can be replaced by the heavily flawed, and often equally ‘mad’ man, who continuously controls and represses her. Through a diachronic analysis of Bertha Mason and Lucy Snowe in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and Villette, Catherine Earnshaw in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and Helen Graham in Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, this project will demonstrate how and why the middle- class, ‘sane’ and respectable man can be met with character divergences and vices of his own. This undermines his credibility as a ‘doctor’ or a dictator in his treatment of women, which in turn vindicates and questions the validity and the ultimate cause of female ‘madness’ in the first instance. -

Identity and Independence in Jane Eyre

Mid Sweden University English Studies Identity and Independence in Jane Eyre Angela Andersson English C/ Special Project Tutor: Joakim Wrethed Spring 2011 1 Table of Content Introduction……………………………………………… 2 Aim and Approach ………………………………………. 2 Theory …………………………………………………… 3 Material and Previous Research…………………………. 5 Analysis………………………………………………….. 6 Gateshead Hall and Lowood Institution………………... 6 Thornfield Hall…………………………………………... 9 Marsh End………………………………………………. 12 Conclusion………………………………………………. 14 Works cited……………………………………………… 15 2 Introduction During the Victorian era the ideal woman‟s life revolved around the domestic sphere of her family and the home. Middle class women were brought up to “be pure and innocent, tender and sexually undemanding, submissive and obedient” to fit the glorified “Angel in the House”, the Madonna-image of the time (Lundén et al, 147). A woman had no rights of her own and; she was expected to marry and become the servant of her husband. Few professions other than that of a governess were open to educated women of the time who needed a means to support themselves. Higher education was considered wasted on women because they were considered mentally inferior to men and moreover, work was believed to make them ill. The education of women consisted of learning to sing, dance, and play the piano, to draw, read, write, some arithmetic and French and to do embroidery (Lundén et al 147). Girls were basically educated to be on display as ornaments. Women were not expected to express opinions of their own outside a very limited range of subjects, and certainly not be on a quest for own identity and aim to become independent such as the protagonist in Charlotte Brontë‟s Jane Eyre. -

Music Theatre

THEATRE So back to the search engine. Add Wales to music theatre in the subject box and it Music theatre obligingly comes up with Music Theatre A radical aesthetic Wales, the Cardiff-based company whose work is regarded as the finest in Britain and rather than a form among the very finest anywhere. The company took its cue from the progressive Rian Evans ideals of the English Opera Group (later the English Music Theatre Company) originally formed by Benjamin Britten at Aldeburgh. However, since what Music As the countdown to the opening of the Theatre Wales stages is primarily Wales Millennium Centre gathers pace, contemporary chamber opera, our original Rian Evans laments the lack of a suitable question immediately poses itself once space for the performance of music again. theatre, and suggests how this difficulty Perhaps the reality is that music theatre is might be overcome so that one of Wales’s a radical aesethetic rather than a form. It has most progressive theatre forms can be its roots in the experimental work of the enjoyed and celebrated by a wider 1960s which attempted to shed the audience. perceived excesses of opera. Its defining characteristic is a greater emphasis on the dramatic and the visual rather than on The advent of the Wales Millennium simply musical elements. That emphasis Centre will change our perspective on ought, in theory, only to be further many aspects of what Richard Eyre has enhanced in today’s climate with the new termed lyric theatre, so it is perhaps timely freedom offered by a greater naturalism on to look at the challenge this presents for the one hand and by up-to-the-minute music theatre in particular. -

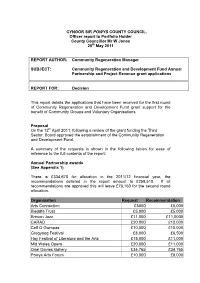

Community Regeneration and Development Fund Annual Partnership and Project Revenue Grant Applications

CYNGOR SIR POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL. Officer report to Portfolio Holder County Councillor Mr W Jones 25 th May 2011 REPORT AUTHOR: Community Regeneration Manager SUBJECT: Community Regeneration and Development Fund Annual Partnership and Project Revenue grant applications REPORT FOR: Decision This report details the applications that have been received for the first round of Community Regeneration and Development Fund grant support for the benefit of Community Groups and Voluntary Organisations. Proposal On the 12 th April 2011, following a review of the grant funding the Third Sector, Board approved the establishment of the Community Regeneration and Development Fund. A summary of the requests is shown in the following tables for ease of reference to the full contents of the report: Annual Partnership awards (See Appendix 1) There is £334,670 for allocation in the 2011/12 financial year, the recommendations detailed in the report amount to £258,510. If all recommendations are approved this will leave £76,160 for the second round allocation. Organisation Request Recommendation Arts Connection £5000 £5,000 Bleddfa Trust £5,000 £5,000 Brecon Jazz £11,000 £11,0000 CARAD £20,000 £12,000 Celf O Gwmpas £10,000 £10,000 Gregynog Festival £8,000 £6,500 Hay Festival of Literature and the Arts £15,000 £11,000 Mid Wales Opera £20,000 £11,000 Oriel Davies Gallery £34,765 £34,765 Powys Arts Forum £10,000 £8,000 Powys Association Of Voluntary Organisations £30,000 £30,000 Powys Leisure Services £24,000 £12,000 Play Montgomeryshire £15,000 £15,000 Powys Federation of Women’s Institutes £2,400 £2,400 Presteigne Festival of the Arts £10,000 £9,000 Presteigne Shire Hall Museum Trust Ltd £7,500 £7,500 Wyeside Arts Centre £47,025 £47,025 Llandrindod Wells Victorian Festival £11,000 £11,000 Wales Pre-school Playgroup Assoc.