Visual Interpretations of the Score in Painting and Digital Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artists' Lives

National Life Stories The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB Tel: 020 7412 7404 Email: [email protected] Artists’ Lives C466: Interviews complete and in-progress (at January 2019) Please note: access to each recording is determined by a signed Recording Agreement, agreed by the artist and National Life Stories at the British Library. Some of the recordings are closed – either in full or in part – for a number of years at the request of the artist. For full information on the access to each recording, and to review a detailed summary of a recording’s content, see each individual catalogue entry on the Sound and Moving Image catalogue: http://sami.bl.uk . EILEEN AGAR PATRICK BOURNE ELISABETH COLLINS IVOR ABRAHAMS DENIS BOWEN MICHAEL COMPTON NORMAN ACKROYD FRANK BOWLING ANGELA CONNER NORMAN ADAMS ALAN BOWNESS MILEIN COSMAN ANNA ADAMS SARAH BOWNESS STEPHEN COX CRAIGIE AITCHISON IAN BREAKWELL TONY CRAGG EDWARD ALLINGTON GUY BRETT MICHAEL CRAIG-MARTIN ALEXANDER ANTRIM STUART BRISLEY JOHN CRAXTON RASHEED ARAEEN RALPH BROWN DENNIS CREFFIELD EDWARD ARDIZZONE ANNE BUCHANAN CROSBY KEITH CRITCHLOW DIANA ARMFIELD STEPHEN BUCKLEY VICTORIA CROWE KENNETH ARMITAGE ROD BUGG KEN CURRIE MARIT ASCHAN LAURENCE BURT PENELOPE CURTIS ROY ASCOTT ROSEMARY BUTLER SIMON CUTTS FRANK AVRAY WILSON JOHN BYRNE ALAN DAVIE GILLIAN AYRES SHIRLEY CAMERON DINORA DAVIES-REES WILLIAM BAILLIE KEN CAMPBELL AILIAN DAY PHYLLIDA BARLOW STEVEN CAMPBELL PETER DE FRANCIA WILHELMINA BARNS- CHARLES CAREY ROGER DE GREY GRAHAM NANCY CARLINE JOSEFINA DE WENDY BARON ANTHONY CARO VASCONCELLOS -

Tate Report 2010-11: List of Tate Archive Accessions

Tate Report 10–11 Tate Tate Report 10 –11 It is the exceptional generosity and vision If you would like to find out more about Published 2011 by of individuals, corporations and numerous how you can become involved and help order of the Tate Trustees by Tate private foundations and public-sector bodies support Tate, please contact us at: Publishing, a division of Tate Enterprises that has helped Tate to become what it is Ltd, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG today and enabled us to: Development Office www.tate.org.uk/publishing Tate Offer innovative, landmark exhibitions Millbank © Tate 2011 and Collection displays London SW1P 4RG ISBN 978-1-84976-044-7 Tel +44 (0)20 7887 4900 Develop imaginative learning programmes Fax +44 (0)20 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Strengthen and extend the range of our American Patrons of Tate Collection, and conserve and care for it Every effort has been made to locate the 520 West 27 Street Unit 404 copyright owners of images included in New York, NY 10001 Advance innovative scholarship and research this report and to meet their requirements. USA The publishers apologise for any Tel +1 212 643 2818 Ensure that our galleries are accessible and omissions, which they will be pleased Fax +1 212 643 1001 continue to meet the needs of our visitors. to rectify at the earliest opportunity. Or visit us at Produced, written and edited by www.tate.org.uk/support Helen Beeckmans, Oliver Bennett, Lee Cheshire, Ruth Findlay, Masina Frost, Tate Directors serving in 2010-11 Celeste -

Jeffrey Steele

Jeffrey Steele RCM Galerie Jeffrey Steele La structure et le rythme La structure et le rythme : sur l’art de Jeffrey Steele Le peintre britannique Jeffrey Steele a été l’une des figures artistiques les plus en vue au sein de ce grand mouvement qui a animé les années 1960, l’art cinétique. Grâce à un seul tableau, peint en 1964, immédiatement devenu l’archétype de ce qu’un journaliste de Time Magazine désigna sous l’abréviation d’ Op Art pour Optical Art, en prenant bien le soin d’annoncer dans le titre de l’article sa teneur : « Pictures that attack the Eye ». Pour l’Amé- rique, le ton était donné. L’oeuvre intitulée Baroque Experiment - Fred Maddox devint tout de suite emblématique de la grande exposition internationale The Responsive Eye, qui fut organisée l’année suivante au Museum of Modern Art à New York par William C. Seitz et qui connut malgré les réserves d’une partie du public et de la presse en général un grand retentissement. Baroque Experiment - Fred Maddox, le tableau de Jeffrey Steele aujourd’hui chez un col- lectionneur brésilien, est en effet exemplaire de son art : abstrait, géométrique, bi-dimen- sionnel, fortement structuré par un ensemble de rectangles concentriques partant du centre et augmentant vers la périphérie, en même temps déstabilisé par le basculement de ses élé- ments dans un sens et dans l’autre. Les espaces ainsi créés se trouvent entièrement occupés d’une même forme en demi - lune répétée dont la hauteur est proportionnelle à la largeur des espaces. Le noyau central quant à lui est tapissé de cercles pleins. -

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 11, Not Necessarily "English Music": Britain's Second Golden Age. (2001), pp. 5-11. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0961-1215%282001%2911%3C5%3ATSOAVA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V Leonardo Music Journal is currently published by The MIT Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mitpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Sep 29 14:25:36 2007 The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts ' The Scratch Orchestra, formed In London in 1969 by Cornelius Cardew, Michael Parsons and Howard Skempton, included VI- sual and performance artists as Michael Parsons well as musicians and other partici- pants from diverse backgrounds, many of them without formal train- ing. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Michael Kidner Interviewed by Penelope Curtis

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ARTISTS’ LIVES Michael Kidner Interviewed by Penelope Curtis & Cathy Courtney C466/40 This transcript is copyright of the British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] This transcript is accessible via the British Library’s Archival Sound Recordings website. Visit http://sounds.bl.uk for further information about the interview. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk IMPORTANT Access to this interview and transcript is for private research only. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators ( [email protected] ) © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C466/40/01-08 Digitised from cassette originals Collection title: Artists’ Lives Interviewee’s surname: Kidner Title: Interviewee’s forename: Michael Sex: Male Occupation: Dates: 1917 Dates of recording: 16.3.1996, 29.3.1996, 4.8.1996 Location of interview: Interviewee’s home Name of interviewer: Penelope Curtis and Cathy Courtney Type of recorder: Marantz CP430 and two lapel mics Recording format: TDK C60 Cassettes F numbers of playback cassettes: F5079-F5085, F5449 Total no. -

Michael Berkeley and David Malouf's Rewriting of Jane Eyre: an Operatic and Literary Palimpsest*

CHAPTER 6 Michael Berkeley and David Malouf’s Rewriting of Jane Eyre: An Operatic and Literary Palimpsest* Jean-Philippe Heberlé English composer Michael Berkeley (born 1948) is the son of Lennox Berkeley (1903–1989), himself a composer of instrumental music and operas including, for instance, A Dinner Engagement (1955) and Ruth (1955–56). To this day, Michael Berkeley has written three operas and is currently working on a new operatic project based on Ian McEwan’s novel Atonement (2001). For his first two operas (Baa Baa Black Sheep, 1993, and Jane Eyre, 2000), he collaborated with acclaimed Australian novelist David Malouf (born 1934). This chap- ter addresses Berkeley’s second opera, Jane Eyre, a chamber opera1 premiered at the Cheltenham Music Festival on June 30, 2000. The opera by David Malouf and Michael Berkeley appears to be an oper- atic and literary palimpsest in which Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is compressed and distorted into a concentrated operatic drama of little more than 70 minutes.2 Five characters form the cast, and the storyline focuses exclusively on the events at Thornfield. In this intertextual3 and intermedial4 analysis of Berkeley and Malouf’s operatic adapta- tion of Jane Eyre, a study of the text and the music reveals whether the librettist and the composer focalized or not on particular elements and episodes of the original novel. The artists at times amended, dis- torted, or retained elements of the novel, allowing their new work to interpret Charlotte Brontë’s novel’s psychologically developed char- acters and its gothic atmosphere. Finally, the opera and its libretto function metadramatically. -

Michael Berkeley Selected Reviews

Michael Berkeley Selected Reviews Winter Fragments (Chamber Music Recording) Resonus Classics RES10223 (September 2018) “Stylistically ranging from the plainchant-inspired Clarinet Quintet (1983) to the sensuous and Satie-like Seven (2007), to the jostling intensity of Catch Me If You Can (1994), it shows Berkeley at his exploratory and individualistic best, free to follow his instinct, tonal or expressionistic” – Fiona Maddocks, The Guardian “Even when working with large-scale forces such as opera and music theatre, Michael Berkeley's style and expression remain attuned to the more intimate nuances of chamber music. Perhaps this is because the chamber context provides such an effective vehicle for one of his music's most distinctive features - the often dichotomous interplay between the individual and the group... the Berkeley Ensemble, directed by Dominic Grier, are excellent throughout - entirely at one with the music of their namesake composer” – Pwyll ap Sion, Gramophone “There’s contrast aplenty – Catch Me If You Can (1994) a feisty, frenetic triptych, the gentle, self-echoing, harp-centred Seven (2007) pregnant with a pensiveness that collides late Mahler with Satie at his most subdued. The Clarinet Quintet (1983) is spun from sinewy, twisting strands contrasting the playful impetuosity and dark-hued luminosity of John Slack’s clarinet to end in a moment of sublimely subdued beauty. 2010’s Rilke-setting Sonnet for Orpheus and the seven-part song-cycle Winter Fragments (1996) – both benefiting from Fleur Barron’s ardent mezzo – -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETII-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND THEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTIIORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISII ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME III Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA eT...........................•.•........•........................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................... xi CHAPTER l:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION J THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Chapter 6 : the Modernist Experiment

PART 2 - NEW MORALITIES AND NEW RULES Chapter 6 : The Modernist Experiment • The Modern period, which was set on its way in the 1860s, 1870s, 1880s CHAPTER 6 and 1890s by Manet, Monet, Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, Georges Seurat, Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Emile Bernard, et al. It is now fashionable to claim that we have entered a Post-Modernist phase. Whether we have or not is a question faced in Chapter 9. The Modernist experiment Though it seems reasonable to include many aspects of painting as defining characteristics of Modernism, there is one, above all, which in recent years has been the butt of vigorous criticism. This is the emphasis on formal properties Introductory (sometimes described as “painting for paintings sake”) at the expense of both symbolic content and social relevance. However, many, like myself, consider The purpose of this chapter is: (a) to summarise and extend ideas on Mod- that much of this criticism misses the mark. On the one hand, it fails to acknowl- ernism in panting discussed in earlier chapters (and other volumes in the se- edge the view, which prevailed amongst the artists concerned, that working with ries); (b) to provide clarifications of its main essentials of Modernism; (c) to colour, line and/or the surface/space dynamic can have profound symbolic signif- give an idea of the variety of its manifestations in its early years. (d) to provide icance and social relevance. On the other, it gives no cognizance to the richness a flavour of the many ways Modernist Painters (starting with the Impression- of the response of the Impressionists and their successors to the two fundamental ists) have struggled with the problems of creativity; and, (e) to show how artists questions that were first given serious consideration in the late 1860s, namely, have always needed the constraint of a framework of ideas to push them forward “What is art?” and “Has the artist any valid role in society?” into the new territory. -

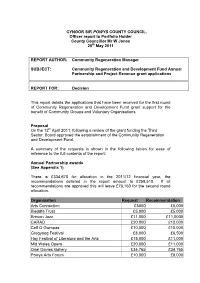

Community Regeneration and Development Fund Annual Partnership and Project Revenue Grant Applications

CYNGOR SIR POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL. Officer report to Portfolio Holder County Councillor Mr W Jones 25 th May 2011 REPORT AUTHOR: Community Regeneration Manager SUBJECT: Community Regeneration and Development Fund Annual Partnership and Project Revenue grant applications REPORT FOR: Decision This report details the applications that have been received for the first round of Community Regeneration and Development Fund grant support for the benefit of Community Groups and Voluntary Organisations. Proposal On the 12 th April 2011, following a review of the grant funding the Third Sector, Board approved the establishment of the Community Regeneration and Development Fund. A summary of the requests is shown in the following tables for ease of reference to the full contents of the report: Annual Partnership awards (See Appendix 1) There is £334,670 for allocation in the 2011/12 financial year, the recommendations detailed in the report amount to £258,510. If all recommendations are approved this will leave £76,160 for the second round allocation. Organisation Request Recommendation Arts Connection £5000 £5,000 Bleddfa Trust £5,000 £5,000 Brecon Jazz £11,000 £11,0000 CARAD £20,000 £12,000 Celf O Gwmpas £10,000 £10,000 Gregynog Festival £8,000 £6,500 Hay Festival of Literature and the Arts £15,000 £11,000 Mid Wales Opera £20,000 £11,000 Oriel Davies Gallery £34,765 £34,765 Powys Arts Forum £10,000 £8,000 Powys Association Of Voluntary Organisations £30,000 £30,000 Powys Leisure Services £24,000 £12,000 Play Montgomeryshire £15,000 £15,000 Powys Federation of Women’s Institutes £2,400 £2,400 Presteigne Festival of the Arts £10,000 £9,000 Presteigne Shire Hall Museum Trust Ltd £7,500 £7,500 Wyeside Arts Centre £47,025 £47,025 Llandrindod Wells Victorian Festival £11,000 £11,000 Wales Pre-school Playgroup Assoc. -

Annual Report October 2011–September 2013

HOUSE OF LORDS APPOINTMENTS COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT October 2011 to September 2013 House of Lords Appointments Commission Page 3 Contents Section 1: The Appointments Commission 5 Section 2: Appointments of non-party-political peers 8 Section 3: Vetting party-political nominees 11 Annex A: Biographies of the Commission 14 Annex B: Individuals vetted by the Commission 16 and appointed to the House of Lords [Group photo] Page 4 Section 1 The Appointments Commission 1. In May 2000 the Prime Minister established the House of Lords Appointments Commission as an independent, advisory, non-departmental public body. Commission Membership 2. The Commission has seven members, including the Chairman. Three members represent the main political parties and ensure that the Commission has expert knowledge of the House of Lords. The other members, including the Chairman, are independent of government and political parties. The independent members were appointed in October 2008 by open competition, in accordance with the code of the Commissioner for Public Appointments. The party-political members are all members of the House of Lords and were nominated by the respective party leader in November 2010 for three year terms. 3. The terms of all members therefore come to an end in the autumn of 2013. 4. Biographies of the Commission members can be seen at Annex A. 5. The Commission is supported by a small secretariat at 1 Horse Guards Road, London SW1A 2HQ. Role of the House of Lords Appointments Commission 6. The role of the Commission is to: make recommendations for the appointment of non-party-political members of the House of Lords; and vet for propriety recommendations to the House of Lords, including those put forward by the political parties and Prime Minister.