Quaternary Landscape Evolution 2011 in the Peribaltic Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abfuhrkalender Für Utting Für Das Jahr 2021

Entsorgung von Sperrmüll e Um eine Abholung des Sperrmülls durch das Abfuhrunternehmen zu bestellen, wird eine Sperrmüllkarte benötigt. Diese Karten werden an die Grundstückseigentümer versandt. he Haushalt Abfuhrkalender 2021 Mieter müssen sich also an den Vermieter oder Hausverwalter wenden. Pro auf einem Grund- stück aufgestellter Mülltonne erhält der Grundstückseigentümer eine Sperrmüllkarte pro des Landkreises Landsberg am Lech Jahr. Die Karte für das Jahr 2021 ist blau. An sämtlic www.abfallberatung-landsberg.de Die Sperrmüllkarte berechtigt Entweder für: zur Bestellung einer Abholung durch das Abfuhrunternehmen gegen eine Anfahrts- pauschale von 50,– €. Pro Sperrmüllkarte werden maximal 3 cbm abgeholt. Utting Konzeption und Gestaltung: abavo GmbH, Buchloe abavo Gestaltung: und Konzeption oder Prittriching Egling zur Selbstanlieferung von bis zu 500 kg Sperrmüll zum Abfallwirtschaftszentrum Hofstetten. Scheuring Sperrmüll sind nur Abfälle, die zu sperrig für die Mülltonne sind. Obermeitingen Bau- und Sanierungs abfälle (z.B. Fenster, Bauholz) sind kein Sperrmüll. Geltendorf Weil Hurlach Weitere Informationen entnehmen Sie bitte der Sperrmüllkarte, die jedem Kaufering Grundstückseigentümer zugesandt wurde oder dem Internet. Eresing Eching Igling Penzing Greifen- brerg Windach Gelbe Tonnen für die Entsorgung von Leichtverpackungen Landsberg Schon- Bei Fragen zur Verteilung, Bereitstellung und Leerung der Gelben Tonnen für die Leicht- dorf Schwifting verpackungen wenden Sie sich bitte an Pürgen Utting Fa. Kühl Entsorgung & Recycling GmbH, Augsburg Finning Kostenfreie Servicenummer: 0800 40 200 40 Hofstetten Ammersee [email protected] Unterdießen Die Sammelkriterien und die Leerungstermine fi nden Sie auch auf den Internetseiten des Thaining Landkreises. Vilgertshofen Dießen Fuchstal Reichling Bei Fragen stehen Ihnen die Mitarbeiter(innen) Leeder Rott der Kommunalen Abfallwirtschaft gerne telefonisch zur Verfügung: Denklingen Apfel- dorf Müllabfuhr: Kostenfreie Servicenummer: 0800 800 300 6 Kinsau Montags alle 14 Tage Abfallberatung: Tel. -

![[Rieseby 2025]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8802/rieseby-2025-18802.webp)

[Rieseby 2025]

[RIESEBY 2025] 1 Bestandaufnahme [RIESEBY 2025] Leitbildprozess zur Ortsentwicklung - [Rieseby 2025] Themen: Wohnen, Einzelhandel, Soziale Infrastruktur und gemeindeeigene Immobilien 1. Modul – Bestandsanalyse zu den o.g. Themen (Fokus OT Rieseby) Bevölkerungsentwicklung und Wohnungsmarkt Einzelhandel Soziale Einrichtungen – gemeindeeigene Immobilien Stärken-Schwächen-Analyse 2. Modul - Handlungsfelder / Entwicklungspotenziale Entwicklungsbedarf Wohnen Entwicklungsperspektiven des Einzelhandels Entwicklungsmöglichkeiten der gemeindeeigenen Immobilien Veränderungspotenzial im Ortskern 3. Modul – Zukunftsgespräch (Der Themenbereich Einzelhandel wird vom Büro Lademann und Partner bearbeitet) 2 Bestandaufnahme [RIESEBY 2025] Bevölkerungsentwicklung und Wohnungsmarkt 3 Bestandaufnahme [RIESEBY 2025] Bevölkerungsentwicklung in der Gemeinde Rieseby Quellen: Regionalplan für den Planungsraum III 2002, S: 70; Statistikamt Nord, A I 1 - j/94 S, A I 1 - j/99 S, A I 1 - j/04 S, A I 1 - j/09 S, A I 1 - j/12 S; Statistikamt Nord, Zensus-Daten vom 09.05.2011 4 Bestandsaufnahme [RIESEBY 2025] Altersstruktur 2011 im regionalen Vergleich 45 39,2 40 38,5 37,7 37,3 35 30 23,9 25 23 22,5 22 21,4 18,6 18,2 20 14,6 15 12,5 12,4 12,1 10,3 9,2 10 8,9 7,8 7,7 5 0 unter 18 J. 18-39 J. 40-64 J. 65-74 J. 75 J. u. älter Gemeinde Rieseby Amt Schlei-Ostsee Kreis Rendsburg-Eckernförde Land Schleswig-Holstein Quelle: Statistik Amt Nord Zensus-Daten vom 09.05.2011 5 Bestandaufnahme [RIESEBY 2025] Entwicklung von Bevölkerung und Wohneinheiten 3.000 2.563 2.602 2.502 2.456 -

Abfuhrkalender 2021 Mieter Müssen Sich Also an Den Vermieter Oder Hausverwalter Wenden

Entsorgung von Sperrmüll e Um eine Abholung des Sperrmülls durch das Abfuhrunternehmen zu bestellen, wird eine Sperrmüllkarte benötigt. Diese Karten werden an die Grundstückseigentümer versandt. he Haushalt Abfuhrkalender 2021 Mieter müssen sich also an den Vermieter oder Hausverwalter wenden. Pro auf einem Grund- stück aufgestellter Mülltonne erhält der Grundstückseigentümer eine Sperrmüllkarte pro des Landkreises Landsberg am Lech Jahr. Die Karte für das Jahr 2021 ist blau. An sämtlic www.abfallberatung-landsberg.de Die Sperrmüllkarte berechtigt für: Entweder Hurlach zur Bestellung einer Abholung durch das Abfuhrunternehmen gegen eine Anfahrts- pauschale von 50,– €. Pro Sperrmüllkarte werden maximal 3 cbm abgeholt. Konzeption und Gestaltung: abavo GmbH, Buchloe abavo Gestaltung: und Konzeption Obermeitingen Prittriching oder Egling zur Selbstanlieferung von bis zu 500 kg Sperrmüll zum Abfallwirtschaftszentrum Scheuring Hofstetten. Sperrmüll sind nur Abfälle, die zu sperrig für die Mülltonne sind. Obermeitingen Geltendorf Bau- und Sanierungs abfälle (z.B. Fenster, Bauholz) sind kein Sperrmüll. Weil Hurlach Weitere Informationen entnehmen Sie bitte der Sperrmüllkarte, die jedem Kaufering Eresing Eching Grundstückseigentümer zugesandt wurde oder dem Internet. Igling Penzing Greifen- brerg ACHTUNG Windach ! Landsberg Gelbe Tonnen für die Entsorgung von Leichtverpackungen Schon- Neue Abfuhrtage dorf Bei Fragen zur Verteilung, Bereitstellung und Leerung der Gelben Tonnen für die Leicht- Schwifting für die Gelbe Tonne verpackungen wenden Sie -

Festschrift Halt Der Vereine Soll Dabei Besonders Erst Möglich Gemacht Haben

100 Jahre Musikverein Reichling 70 Jahre Landjugend Reichling 48. Bezirksmusikfest, 49. Bezirkslandjugendtag FFeeFestsstage tvtomss 12. cbcis 16hh. Seprrtemiibeffr 20tt 19 Inhalt Grußworte Schirmherrin, Landrat, Vorsitzende und Dirigent, 5 Vorstände Ort, Kreis, Bezirk Der Musikverein Reichling Aus unserer 100-jährigen Geschichte 22 Sag mir, was du spiels t ... - der etwas andere Psycho-Test 30 48. Bezirksmusikfest: Ergebnisse der Wertungsspiele 38 Der Bezirksverband Lech-Ammersee: ein Porträt 41 Jungbläser Lechrain: Musikspielen? Kinderleicht! 43 Die Landjugend Reichling Höhepunkte seit der Gründung 48 Wichtige Personen unserer Geschichte 52 Tradition: Maibaumstehlen, Bayernhymne 54 Die Festtage Alle Höhepunkte der Festwoche im September 63 Festzug-Aufstellun g/ Karte 68 Impressionen 79 Dan k/ Impressum 92 3 100 Jahre Musik Verein t Reichling Anzeigen Grußwort des Landrates 70 Jahre Landjugend Reichling Liebe Festvereine, liebe Reichlingerinnen und Reichlinger, liebe Festgäste eichling steht in diesen Tagen ihren eigenen ganz im Zeichen gleich zweier Stempel auf - gRroßer Feste und Jubiläen. Der Mu - drücken und sikverein richtet das 48. Bezirksmu - etwas für sikfest und die Landjugend den 49. Kultur, Ge - Bezirkslandjugendtag aus. Und so meinschaft gratuliere ich dem Musikverein und Gesel - Reichling sehr herzlich zum 100. Ge - ligkeit tun. burtstag. Ebenso herzlich gratuliere Jede Ge - ich der Reichlinger Landjugend, die meinde lebt nun bereits auf 70 Jahre Vereinsge - von solch hervorragendem, freiwilli - schichte zurückblicken darf. gem Engagement wie es beim Musik - verein und der Landjugend so lange Es wird also einiges los sein an den schon da ist. Festtagen, die Reichlingerinnen und Reichlinger sind gerne Gastgeber. Ein Ich beglückwünsche nochmals die ganzes Dorf wird für Geselligkeit, beiden Festvereine und wünsche wei - Gemütlichkeit, Stimmung und Har - terhin viel Erfolg, eine erfolgreiche monie sorgen. -

170 Cdu-Kreisverband Rendsburg-Eckernförde

ARCHIV FÜR CHRISTLICH-DEMOKRATISCHE POLITIK DER KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG E.V. 02 – 170 CDU-KREISVERBAND RENDSBURG-ECKERNFÖRDE SANKT AUGUSTIN 2016 I Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Chroniken, Jubiläen 1 2 Kreisparteitage 2 3 Kreisvorstand 3 3.1 Sitzungen 3 3.2 Korrespondenz 4 4 Kreisgeschäftsstelle 6 4.1 Schriftwechsel 6 4.1.1 Landesgeschäftsstelle 6 4.1.2 Bundesgeschäftsstelle 6 4.2 Rundschreiben 6 4.3 Veranstaltungen 7 4.4 Mitglieder 7 5 Vereinigungen, Ausschüsse, Arbeitskreise 8 6 Ortsverbände und Amtsverbände 13 6.1 Ortsverbände 13 6.1.1 Ortsverband Rendsburg 50 6.2 Ämter/Amtsverbände 52 7 Wahlen 55 7.1 Kommunalwahlen 55 7.2 Landtagswahlen 56 7.3 Bundestagswahlen 57 7.4 Europawahlen 58 8 Kreistags- und Rathausfraktion 59 8.1 Kreistagsfraktion 59 8.2 Rathausfraktion 60 9 Presse 61 Sachbegriff-Register 62 Ortsregister 64 Personenregister 65 Literatur: 40 Jahre CDU-Kreisverband 5.12.1945 bis 5.12.1985. CDU Rendsburg-Eckernförde, Rendsburg 1985; 50 Jahre CDU-Kreisverband 5.12.1945 bis 5.12.1995. CDU Rendsburg-Eckernförde, Schleswig 1995; 60 Jahre CDU-Kreisverband Rendsburg-Eckernförde, 1945-2005, Rendsburg 2005. Bestandsbeschreibung: Die Akten des Kreisverbands Rendsburg-Eckernförde wurden 1987 von Frau Dr. Blumenberg-Lampe in das Archiv übernommen. Nachlieferungen erfolgten im September 1989, im Mai 2002 und im April 2005, im Januar 2009 und im März 2015. Der Kreisverband Rendsburg-Eckernförde entstand am 30. Januar 1970 aus dem Zusammenschluss der beiden Kreisverbände Rendsburg und Eckernförde. Der Kreisverband Rendsburg wurde bereits am 5. Dezember 1945 von Adolf Steckel, Detlef Struve und Theodor Steltzer gegründet. Der Kreisverband Eckernförde entstand erst 1948. Material aus der Zeit vor dem Zusammenschluss ist nicht in das Archiv gelangt. -

Medtech Companies

VOLUME 5 2020 Medtech Companies Exclusive Distribution Partner Medtech needs you: focused partners. Medical Technology Expo 5 – 7 May 2020 · Messe Stuttgart Enjoy a promising package of benefits with T4M: a trade fair, forums, workshops and networking opportunities. Discover new technologies, innovative processes and a wide range of materials for the production and manufacturing of medical technology. Get your free ticket! Promotion code: MedtechZwo4U T4M_AZ_AL_190x250mm_EN_C1_RZ.indd 1 29.11.19 14:07 Medtech Companies © BIOCOM AG, Berlin 2020 Guide to German Medtech Companies Published by: BIOCOM AG Luetzowstrasse 33–36 10785 Berlin Germany Tel. +49-30-264921-0 Fax +49-30-264921-11 [email protected] www.biocom.de Find the digital issues and Executive Producer: Marco Fegers much more on our free app Editorial team: Sandra Wirsching, Jessica Schulze in the following stores or at Production Editor: Benjamin Röbig Graphic Design: Michaela Reblin biocom.de/app Printed at: Heenemann, Berlin Pictures: Siemens (p. 7), Biotronik (p. 8), metamorworks/ istockphoto.com (p. 9), Fraunhofer IGB (p. 10) This book is protected by copyright. All rights including those regarding translation, reprinting and reproduction reserved. tinyurl.com/y8rj2oal No part of this book covered by the copyright hereon may be processed, reproduced, and proliferated in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or via information storage and retrieval systems, and the Internet). ISBN: 978-3-928383-74-5 tinyurl.com/y7xulrce 2 Editorial Medtech made in Germany The medical technology sector is a well-established pillar within the healthcare in- dustry in Germany and one of the major drivers of the country’s export-driven eco- nomic growth. -

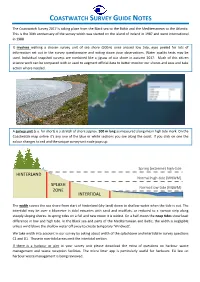

Survey Guide Notes 2017

COASTWATCH SURVEY GUIDE NOTES The Coastwatch Survey 2017 is taking place from the Black sea to the Baltic and the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. This is the 30th anniversary of the survey which was started on the island of Ireland in 1987 and went international in 1988. It involves walking a chosen survey unit of sea shore (500m) once around low tide, eyes peeled for lots of information set out in the survey questionnaire and noting down your observations. Water quality tests may be used. Individual snapshot surveys are combined like a jigsaw of our shore in autumn 2017. Much of this citizen science work can be compared with or used to augment official data to better monitor our shores and seas and take action where needed. A survey unit (s.u. for short) is a stretch of shore approx. 500 m long as measured along mean high tide mark. On the Coastwatch map online it’s any one of the blue or white sections you see along the coast. If you click on one the colour changes to red and the unique survey unit code pops up. Spring (extreme) high-tide HINTERLAND Normal high-tide (MHWM) SPLASH Normal low-tide (MLWM) ZONE INTERTIDAL The width covers the sea shore from start of hinterland (dry land) down to shallow water when the tide is out. The intertidal may be over a kilometre in tidal estuaries with sand and mudflats, or reduced to a narrow strip along steeply sloping shores. In spring tides on a full and new moon it is widest. -

Abstracts of the 25Th International Diatom Symposium Berlin 25–30 June 2018 – Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin Freie Universität Berlin

Abstracts of the 25th International Diatom Symposium Berlin 25–30 June 2018 Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin Abstracts of the 25th International Diatom Symposium Berlin 25–30 June 2018 – Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin Freie Universität Berlin 25th International Diatom Symposium – Berlin 2018 Published by BGBM Press Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin Freie Universität Berlin LOCAL ORGANIZING COMMITTEE: Nélida Abarca, Regine Jahn, Wolf-Henning Kusber, Demetrio Mora, Jonas Zimmermann YOUNG DIATOMISTS: Xavier Benito Granell, USA; Andrea Burfeid, Spain; Demetrio Mora, Germany; Hannah Vossel, Germany SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE: Leanne Armand, Australia; Eileen Cox, UK; Sarah Davies, UK; Mark Edlund, USA; Paul Hamilton, Canada; Richard Jordan, Japan; Keely Mills, UK; Reinhard Pienitz, Canada; Marina Potapova, USA; Oscar Romero, Germany; Sarah Spaulding, USA; Ines Sunesen, Argentina; Rosa Trobajo, Spain © 2018 The Authors. The abstracts published in this volume are distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0 – http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). ISBN 978-3-946292-27-2 doi: https://doi.org/10.3372/ids2018 Published online on 25 June 2018 by the Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin – www.bgbm.org CITATION: Kusber W.-H., Abarca N., Van A. L. & Jahn R. (ed.) 2018: Abstracts of the 25th International Diatom Symposium, Berlin 25–30 June 2018. – Berlin: Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin. doi: https://doi.org/10.3372/ids2018 ADDRESS OF THE EDITORS: Wolf-Henning Kusber, Nélida Abarca, Anh Lina Van, Regine Jahn Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin Königin-Luise-Str. -

Faunistisches Fachgutachten (Vögel Und Fledermäuse) Windpark Saxtorf

Faunistisches Fachgutachten (Vögel und Fledermäuse) Windpark Saxtorf (B-Plan Nr.17), Gemeinde Rieseby, Kreis Rendsburg-Eckernförde ! Erstellt im Auftrag der Gemeinde Rieseby Auftragnehmerin: Dipl.Biol. NATASCHA GAEDECKE, Westensee Brennhorsten 13, 24259 Westensee Tel: 0178-1831807, 04305-9913404 Dezember 2020 Faunistisches Fachgutachten Windpark Saxtorf Seite !2 Inhalt 1.1 Einleitung und Veranlassung 4 1.2 Beschreibung des Vorhabengebiets und der Umgebung 4 2 Rechtliche Grundlagen 4 3 Material und Methoden 5 3.1 Untersuchungskonzept 5 3.2 Erfassungsmethodik 5 3.2.1 Erfassung der Brutstandorte von Groß- und Greifvögeln 5 3.2.2 Raumnutzungsanalyse Greif- und Großvögel 6 3.2.3 Rastvogelerfassungen 7 3.2.4 Fledermauserfassungen 8 3.3 Bewertung der ornithologischen Beobachtungen 9 3.4 Bewertung der artspezifischen Empfindlichkeiten (Vögel) 10 3.5 Bewertung der Fledermausaktivität 11 3.6 Bewertung der artspezifischen Empfindlichkeiten (Fledermäuse) 11 4 Bestandsbeschreibung und Bewertung 12 4.1 Greif- und Großvögel 12 4.1.1 Brutplätze der Greif- und Großvögel 12 4.1.2 Potenzielle Beeinträchtigungsbereiche der Brutplätze 15 4.1.3 Raumnutzungsanalyse / Flugaktivität der Greif- und Großvögel 15 4.1.3.1 Seeadler (Haliaeetus albicilla) 16 4.1.3.2 Rotmilan (Milvus milvus) 19 4.1.3.3 Rohrweihe (Circus aeruginosus) 22 4.1.3.4 Baumfalke (Falco subbuteo) 24 4.1.3.5 Wespenbussard (Pernis apivorus) 26 4.1.3.6 Mäusebussard (Buteo buteo) 27 4.1.3.7 Kranich (Grus grus) 27 4.1.3.8 Uhu (Bubo bubo) 29 4.2 Rastvögel 30 4.3 Auswirkungsprognose Groß- und Greifvögel -

Appendix 1 : Marine Habitat Types Definitions. Update Of

Appendix 1 Marine Habitat types definitions. Update of “Interpretation Manual of European Union Habitats” COASTAL AND HALOPHYTIC HABITATS Open sea and tidal areas 1110 Sandbanks which are slightly covered by sea water all the time PAL.CLASS.: 11.125, 11.22, 11.31 1. Definition: Sandbanks are elevated, elongated, rounded or irregular topographic features, permanently submerged and predominantly surrounded by deeper water. They consist mainly of sandy sediments, but larger grain sizes, including boulders and cobbles, or smaller grain sizes including mud may also be present on a sandbank. Banks where sandy sediments occur in a layer over hard substrata are classed as sandbanks if the associated biota are dependent on the sand rather than on the underlying hard substrata. “Slightly covered by sea water all the time” means that above a sandbank the water depth is seldom more than 20 m below chart datum. Sandbanks can, however, extend beneath 20 m below chart datum. It can, therefore, be appropriate to include in designations such areas where they are part of the feature and host its biological assemblages. 2. Characteristic animal and plant species 2.1. Vegetation: North Atlantic including North Sea: Zostera sp., free living species of the Corallinaceae family. On many sandbanks macrophytes do not occur. Central Atlantic Islands (Macaronesian Islands): Cymodocea nodosa and Zostera noltii. On many sandbanks free living species of Corallinaceae are conspicuous elements of biotic assemblages, with relevant role as feeding and nursery grounds for invertebrates and fish. On many sandbanks macrophytes do not occur. Baltic Sea: Zostera sp., Potamogeton spp., Ruppia spp., Tolypella nidifica, Zannichellia spp., carophytes. -

Steckbriefe Und Kartierhinweise Für FFH-Lebensraumtypen

Steckbriefe und Kartierhinweise für FFH-Lebensraumtypen 1. Fassung, Mai 2007 Landesamt für Natur und Umwelt des Landes Schleswig-Holstein LANU Schleswig-Holstein Steckbriefe und Kartierhinweise für FFH-Lebensraumtypen 1. Fassung Mai 2007 EU-Code 1140 Kurzbezeichnung Watten FFH-Richtlinie 1997 Vegetationsfreies Schlick-, Sand- und Mischwatt BFN 1998 Vegetationsfreies Schlick-, Sand- und Mischwatt Interpretation Manual Mudflats and sandflats not covered by seawater at low tide Sands and muds of the coasts of the oceans, their connected seas and as- sociated lagoons, not covered by sea water at low tide, devoid of vascular plants, usually coated by blue algae and diatoms. They are of particular importance as feeding grounds for wildfowl and waders. The diverse inter- tidal communities of invertebrates and algae that occupy them can be used to define subdivisions of 11.27, eelgrass communities that may be exposed for a few hours in the course of every tide have been listed under 11.3, brackish water vegetation of permanent pools by use of those of 11.4. Note: Eelgrass communities (11.3) are included in this habitat type. Beschreibung Sand- und Schlickflächen, die im Küsten- und Brackwasserbereich von Nord- und Ostsee und in angrenzenden Meeresarmen, Strandseen und Salzwiesen bei LAT / lowest astronomical tide (Tidewatten der Nord- see) oder mittlerem Witterungsverlauf (Windwatten der Ostsee) regel- mäßig trocken fallen. Typische Arten Höhere Pflanzen : Eleocharis parvula (Schlei), Oenanthe conioides (Elbe), Ruppia cirrhosa, Ruppia maritima, Zostera marina, Zostera noltii Algen : div. Blau- und Kieselalgen Außerdem Windwatten z. T. mit Armleuchteralgen (Characeae), anderen Makroalgen Typische Vegetation > Zosteretum noltii HARMSEN 1936 > Zosteretum marinae B ORGESEN ex VAN GOOR 1921 > Ruppion maritimae B R.-B L. -

1/98 Germany (Country Code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The

Germany (country code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA), the Federal Network Agency for Electricity, Gas, Telecommunications, Post and Railway, Mainz, announces the National Numbering Plan for Germany: Presentation of E.164 National Numbering Plan for country code +49 (Germany): a) General Survey: Minimum number length (excluding country code): 3 digits Maximum number length (excluding country code): 13 digits (Exceptions: IVPN (NDC 181): 14 digits Paging Services (NDC 168, 169): 14 digits) b) Detailed National Numbering Plan: (1) (2) (3) (4) NDC – National N(S)N Number Length Destination Code or leading digits of Maximum Minimum Usage of E.164 number Additional Information N(S)N – National Length Length Significant Number 115 3 3 Public Service Number for German administration 1160 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 1161 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 137 10 10 Mass-traffic services 15020 11 11 Mobile services (M2M only) Interactive digital media GmbH 15050 11 11 Mobile services NAKA AG 15080 11 11 Mobile services Easy World Call GmbH 1511 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1512 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1514 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1515 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1516 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1517 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1520 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH 1521 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH / MVNO Lycamobile Germany 1522 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone