Niger 2009 Profile Irrigated Zo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Increase Clean Faces! Decrease Flies!

SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS THIRD ANNUAL PROGRAM REVIEW OF CARTER CENTER-ASSISTED TRACHOMA CONTROL PROGRAMS Increase Clean Faces! Decrease Flies! The Carter Center March 11-12, 2002 Funded by: Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Lions Clubs International Foundation ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Carter Center’s Trachoma Control Program is funded through generous grants from the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, the Lions Clubs International Foundation (LCIF), as well as through the generous in-kind donation of Zithromax for some of the countries by Pfizer Inc, through the International Trachoma Initiative. The third annual Program Review for Carter Center-assisted trachoma control programs was made possible through the generosity of the Hilton Foundation, LCIF and Novartis Ophthalmics, North America. The individuals below assisted with the preparation of these proceedings. Their contribution and support are gratefully acknowledged. Ms. Misrak Makonnen The Carter Center Ms. Jennifer Moore The Carter Center Ms. Robin Poovey The Carter Center Note: Inclusion of information in the Trachoma Program Review Proceedings does not constitute “publication” of that information. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The third annual Program Review for Carter Center-assisted trachoma control programs was held on 11-12 March 2002 at The Carter Center’s headquarters in Atlanta. The theme of the meeting was: Increase Clean Faces, Decrease Flies! As in previous years, the objectives of the Program Review were to assess the status of each national trachoma control program, identify challenges encountered in creating national trachoma control programs, assess impediments and problems in program implementation and discuss solutions, as well as to promote sharing and standardization of information. In this, our third year together, special attention was given to improving environmental hygiene, particularly through fly control. -

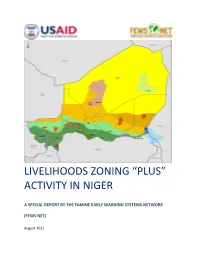

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Profil Des Moyens D'existence Région De Zinder

Profil des moyens d’existence région de Zinder Magaria et Dungass – Zone agricole centrale de culture de céréales et des légumineuses Niger1 1 Ce profil a été réalisé en Mars 2016 dans la zone agricole des départements de Magaria et Dungass–région de Zinder. L’étude a touché particulièrement la zone centrale de culture de mil, sorgho, niébé, arachide et sésame. Les informations présentées font référence à l’année de consommation Octobre 2014– Septembre 2015. À l'exception de changements significatifs de moyens d’existence de la zone, ces informations auront une validité d’environ cinq à dix ans. Profil de Moyens d’Existence – Magaria agricole centrale – département de Magaria - Dungass, région de Zinder—Niger I. Contexte 1.1. Description de la zone Mars 2016 Le département de Magaria est situé au sud du Niger dans la région de Zinder. Il couvre une superficie de 8 434 km² et son chef-lieu est Magaria. Suite à la réforme administrative au Niger de 2011, le département de Magaria a été divisé en deux départements notamment le département de Magaria et Dungass. Le département de Magaria couvre dorénavant les communes rurales de Bandé, Dantchiao, Kwaya, Sassoumbroum, Wacha, Yékoua et a une population d’environ 718 440 habitants en 2016. Le nouveau département de Dungass couvre les communes rurales de Gouchi, Mallawa, Dungass et Dogo Dogo et une population estimée en 2016 à 440 044 habitants ce qui donne une densité d’environ 83 habitants par kilomètre carré. Les deux départements sont limités au nord par les départements de Matamèye et Mirriah, à l'Est par le département de Gouré, au Sud par le Nigéria et à l’Ouest par le département de Tessaoua. -

Niger – Food Insecurity

FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2011 SEPTEMBER 30, 2011 NIGER – FOOD INSECURITY KEY DEVELOPMENTS Following Niger’s food insecurity and acute malnutrition crisis of 2009/2010, food security in Niger generally improved in FY 2011 due to favorable rainfall and harvest patterns and increased grain price stabilization. The 2010 harvest produced an estimated 5.5 million metric tons (MT) of grain, approximately 40 percent above the five-year average. An evaluation of food security conditions conducted by Niger’s national early warning system in May and June 2011 found that approximately 2.3 million people in Niger were food-insecure, a 63 percent decrease from the same period in 2010. In addition, the quantity of food consumed in Niger remains at normal levels, despite an increase in demand due to the return of migrants from Libya, as a result of targeted food distributions to vulnerable households, according to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Despite improved food security conditions in many areas, extreme weather events, including drought and floods, continue to negatively impact agricultural activities in many parts of Niger, as the majority of the predominantly agro- pastoral population relies on a single rainy season for crop cultivation and pasture renewal. Flooding in mid-August, for instance, affected nearly 14,000 people in Tillabéri and Maradi regions, destroying more than 100,000 hectares of crops and 1,000 houses, according to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Due to improved food security and ongoing acute malnutrition relief interventions, the national prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) among children under five years of age decreased to 12.3 percent as of July 2011, a decline from the prevalence of 16.7 percent in November 2010. -

Nutrition Causal Analysis in Niger

Nutrition Causal Analysis in Niger Report of Key Findings March 2017 This publication was prepared by Christine McDonald under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. FEWS NET NCA Research in Niger March 2017 Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………………… 2 Acronyms……...……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 3 1. Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………………………………………. 4 2. Background……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 3. Rationale for NCA Research.…………………………………………………….……………………………………………………………………….. 7 4. Scope and objectives of the NCA study in Maradi and Zinder.……………………..……………………………………………………. 8 5. Local collaboration……………..……………………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………… 8 6. Study setting.……………………..……………………………………………………….………………………………………………………………….… 9 7. Methodology………………………………………………………..……………………………………………………….……………………………….… 12 7.1 Study design and sample size calculations………………………………………..……………………………….…….………… 12 7.2 Sampling strategy………………………………………..………………………………………………………………………..………….. 12 7.3 Survey procedures………………………………………..……………………………………………………………………….………….. 13 7.4 Data entry and analysis………………………………………..………………………………………………………………….………… 14 -

Annual Report

Resilience and Economic Growth in the Sahel - Enhanced Resilience REPUBLICS OF NIGER and BURKINA FASO REGIS-ER Annual Report OCTOBER 1, 2017 TO SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 Revised, December 2018 Cooperative Agreement No. 625-A-14-00001 Blvd. Mali Béro, Rue IB-73 B.P. 12 909, NIAMEY Tel.: (227) 20.35.16.48 Table of Contents I. Executive summary.………………………………………………………………… 3 II. Programs………………………..………………………………………………….... 7 Program 5 – Governance Sub-Section A: Promotion of Local Institutions ................................... 7 Program 1 – Habbanayé plus Animal Health and Feed ................................................................ 9 Program 2 - Horticulture ............................................................................................................... 12 Program 3 – Access to Financial Services ..................................................................................... 15 Program 4 - Resilient Production Systems .................................................................................... 17 Program 5 – Governance Sub-Section B: Natural Resource Management, Disaster Risk Management, Conflict Management and Land Tenure Security ................................................. 19 Program 6 – Water Services ........................................................................................................... 21 Program 7 – Hygiene and Sanitation ........................................................................................... 24 Program 8 – Community-based Health and Nutrition ............................................................... -

Different Conceptions of Food Insecurity and Vulnerability

Report No. 44072-NE Report No. 44072-NE Niger Food Security and Safety Nets Public Disclosure Authorized February 18, 2009 Human Development, AFTH2 Country Department AFCF2 Africa Region Niger Food Security and Safety Nets Food Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized QUIBB Questionnaire sur les Indicateurs de Base et de Bien-&tre UEMOA Union Economique et Mone'taire Ouest Africaine UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund UNDP United Nations Development Program USAID United States Agency for International Development FEWS NET USAID- Famine Early Warning System Network WAEMU West African Economic and Monetary Union WFD World Food Program WHO World Health Organization Vice President: Obiageli Katryn Ezekwesili Country Director Madani M. Tall Sector Director Yaw Ansu Sector Manager Eva Jarawan Task Team Leader Setareh Razmard Carlo Del Ninno ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by a team consisting of Jenny C. Aker (Consultant), Paul Dorosh (FEU), Menno Mulder-Sibanda (AFTH2), Carlo Del Ninno (HDNSP, co-task team leader), and Setareh Razmara (AFTH2, co-task team leader). Valuable inputs were provided by Phillippe George Leite (HDNSP), Koffi Akakpo (VAM Officer WFP - Niger), and Khamada Baye (Local Consultant). The report draws from two background papers that provided substantial inputs: (i)Food Security, Social Safety Nets and Food Crises: Country Experience from Niger (Jenny C. Aker, Consultant); and (ii)Production Shocks, Regional Trade and Cereal Prices in Niger: A (Multi-Market) Simulation Analysis (Paul Dorosh). Valuable guidance and suggestions were provided by Ousman Diagana (Country Manager for Niger); Patrick Verissimo, El Hadj Adama Toure, and Amadou Alassane (AFTAR); Xiao Ye (AFRCE); Richard Seifman and Leandre Bassole (AFTHV); and Amadou Ibrahim (AFTP4). -

C:\Mes Documents\Annuaires\Annu

ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE DU NIGER 2013 - 2017 REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER MINISTERE DU PLAN -©©©- INSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA STATISTIQUE Etablissement Public à Caractère Administratif ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE 2013-2017 Edition 2018 Novembre 2018 1 Institut National de la Statistique ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE DU NIGER 2013 - 2017 2 Institut National de la Statistique ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE DU NIGER 2013 - 2017 ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE 2013 - 2017 EDITION 2018 Novembre 2018 3 Institut National de la Statistique ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE DU NIGER 2013 - 2017 4 Institut National de la Statistique ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE DU NIGER 2013 - 2017 Ce document a été élaboré par : - Sani ALI, Chef de Division de la Coordination Statistique et de la Coopération Ont également participé à l’élaboration de cette publication, les structures et personnes suivantes de l’Institut National de la Statistique (INS) : Les structures : - Direction de la Comptabilité Nationale, de la Conjoncture et des Etudes Economiques (DCNCEE) ; - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Démographiques et Sociales (DSEDS). Les personnes : - Idrissa ALICHINA KOURGUENI, Directeur Général de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Issoufou SAIDOU, Directeur de la Coordination et du Management de l’Information Statistique. Ce document a été examiné et validé par les personnes ci-après : - Maman Laouali ADO, Conseiller du DG/INS ; - Djibo SAIDOU, Inspecteur des Services Statistiques (ISS) ; - Ghalio EKADE, Inspecteur de Services Statistiques (ISS) ; - Sani ALI, Chef de Division de la Coordination Statistique et de -

Pdf | 270.45 Kb

NIGER Monthly Food Security Update March 2006 Alert Level: No alert Watch Warning Emergency SUMMARY Summary of the food and nutrition situation Summary & timeline.................1 The food security situation in Niger as of the month of March was marked by pockets of Current hazard summary .........1 food insecurity in agropastoral and pastoral areas of the country, in the wake of the Food security, health and nutrition depletion of grain reserves, the repayment of debts incurred during last year’s crisis, .................................................2 localized grain and forage deficits and relatively high price levels compared with the five- Stream flow conditions.............4 year average. There has been very little movement in prices for major grain crops since Market situation .......................4 February, but price levels are still relatively high compared with the average, despite a Relief efforts.............................5 good harvest this past growing season. Most likely, this price stability is connected with the improvement in grain availability derived from commercial imports from neighboring countries such as Mali and Nigeria. According to nutrition stakeholders, admissions rates for therapeutic feeding centers in the Maradi and Zinder regions are starting to inch upwards and are expected to pick up even further during the upcoming lean period. As far as health conditions are concerned, according to the National Health Information System (SNIS), 984 cases of meningitis were reported over the period between January 1 and March 21, with 64 fatalities. These localized signs of a deterioration of food security and nutrition warrant the implementation of special programs designed to quickly ease adverse conditions in highly food-insecure areas by strengthening the capacity of local households to deal with a possible serious erosion of their sources of food and income. -

![[Striga Gesnerioides (Wild.) Vatke] RESISTANCE USING MARKER ASSISTED SELECTION in NIGER By](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5643/striga-gesnerioides-wild-vatke-resistance-using-marker-assisted-selection-in-niger-by-6115643.webp)

[Striga Gesnerioides (Wild.) Vatke] RESISTANCE USING MARKER ASSISTED SELECTION in NIGER By

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh BREEDING COWPEA [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.] FOR STRIGA [Striga gesnerioides (Wild.) Vatke] RESISTANCE USING MARKER ASSISTED SELECTION IN NIGER By SALIFOU MAHAMADOU (10359704) THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE IN PLANT BREEDING WEST AFRICA CENTRE FOR CROP IMPROVEMENT COLLEGE OF BASIC AND APPLIED SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF GHANA LEGON DECEMBER, 2015 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ABSTRACT Striga gesnerioides (Wild.)Vatke is one of the main biotic constraints restricting yield of cowpea in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) in general and particularly in Niger. The available resistant varieties developed so far often lack farmers‟ and end-users‟ desired traits and they also show levels of breakdown in resistance. Understanding farmers‟ knowledge regarding production constraints and varietal preferences is invaluable in breeding for cowpea improvement. The development of cowpea varieties by introgressing multiple Striga resistance into adapted genotypes will facilitate the achievement of food security in the country. This study aims to (i) assess farmers‟ preferred traits and perceptions of Striga on cowpea production (ii) identify new sources of Striga resistance in national and other available germplasm (iii) determine the presence of other Striga races besides SG3 in Niger (iv) introgress the resistance gene „Rsg1’ into farmers‟ preferred varieties using marker assisted selection (MAS) (v) assess MAS for selection of Striga resistant genotypes. A participatory rural appraisal technique was used to identify the importance of cowpea in the farming system and its production constraints as well as farmers‟ knowledge on Striga and their cowpea preferred traits. -

Tree Cover Mapping Tool—Documentation and User Manual

Tree Cover Mapping Tool—Documentation and User Manual Open-File Report 2016–1067 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Agroforestry parkland in central Burkina Faso. Tree Cover Mapping Tool—Documentation and User Manual By Suzanne Cotillon and Melissa Mathis Open-File Report 2016–1067 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Cotillon, Suzanne, and Mathis, Melissa, 2016, Tree cover mapping tool—documentation and user manual (ver. 1.0, March 2016): U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2016–1067, 11 p., http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/ofr20161067. ISSN 2331-1258 (online) iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 -

Niger Food Insecurity Fact Sheet #1

FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2011 SEPTEMBER 30, 2011 NIGER – FOOD INSECURITY KEY DEVELOPMENTS Following Niger’s food insecurity and acute malnutrition crisis of 2009/2010, food security in Niger generally improved in FY 2011 due to favorable rainfall and harvest patterns and increased grain price stabilization. The 2010 harvest produced an estimated 5.5 million metric tons (MT) of grain, approximately 40 percent above the five-year average. An evaluation of food security conditions conducted by Niger’s national early warning system in May and June 2011 found that approximately 2.3 million people in Niger were food-insecure, a 63 percent decrease from the same period in 2010. In addition, the quantity of food consumed in Niger remains at normal levels, despite an increase in demand due to the return of migrants from Libya, as a result of targeted food distributions to vulnerable households, according to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Despite improved food security conditions in many areas, extreme weather events, including drought and floods, continue to negatively impact agricultural activities in many parts of Niger, as the majority of the predominantly agro- pastoral population relies on a single rainy season for crop cultivation and pasture renewal. Flooding in mid-August, for instance, affected nearly 14,000 people in Tillabéri and Maradi regions, destroying more than 100,000 hectares of crops and 1,000 houses, according to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Due to improved food security and ongoing acute malnutrition relief interventions, the national prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) among children under five years of age decreased to 12.3 percent as of July 2011, a decline from the prevalence of 16.7 percent in November 2010.