Episodic Memory, Concentrated Attention and Processing Speed in Aging a Comparative Study of Brazilian Age Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory Richard Topolski ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Sarah R. Daniel ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Introduction methodology for measuring EM largely independent of semantic memory. Episodic memory (EM) is composed of personally experienced events in which ‘the what, where, and when’ Method are essential components while semantic memory is simply composed of accumulated facts about the world (Tulving, Happy, neutral, or sad mood states were induced in 88 2002). A wide variety of tasks have been used to tap students via a 20 minute long viewing of either a stand-up episodic memory including: recalling words from an early comedy routine, a documentary, or holocaust footage. learned list; yes-no recognition of previously presented Immediately following the mood induction, participants common objects or pictures; and free recall of past personal engaged in eight interactive tasks which involved both experiences. These tasks are used to evaluate episodic familiar objects (pennies and paperclips) and novel memory because in order to know which words, pictures, or geometric forms created by bending paper clips with blue experiences to retrieve, some contextual (episodic) beads into unique shapes, (Rock, Schreilber, and Ro, 1994). information must first be accessed (Mayes & Roberts, A four-item force-choice recognition test for the novel 2001). While all of these measures seem to share this geometric forms was employed, with the task name serving contextual component, none adequately examines the as the retrieval cue. -

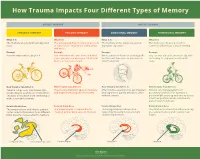

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Episodic Memory-From Brain to Mind

HIPPOCAMPUS 16:691–703 (2006) Episodic Memory—From Brain to Mind Janina Ferbinteanu,* Pamela J. Kennedy, and Matthew L. Shapiro ABSTRACT: Neuronal mechanisms of episodic memory, the conscious by the rapid formation of relational representations of recollection of autobiographical events, are largely unknown because highly processed sensory information that are used electrophysiological studies in humans are conducted only in excep- tional circumstances. Unit recording studies in animals are thus crucial flexibly and are not necessarily expressed through overt for understanding the neurophysiological substrate that enables people motor behavior. Episodic memory is also sensitive to to remember their individual past. Two features of episodic memory— lesions of the prefrontal cortex (Wheeler et al., 1995; autonoetic consciousness, the self-aware ability to \travel through Nyberg et al., 2000; Burgess et al., 2002; Wheeler time", and one-trial learning, the acquisition of information in one and Stuss, 2003), develops later in an individual’s life, occurrence of the event—raise important questions about the validity of animal models and the ability of unit recording studies to capture essen- encodes events within a personal framework, and pos- tial aspects of memory for episodes. We argue that autonoetic experi- sesses a temporal dimension because it is oriented ence is a feature of human consciousness rather than an obligatory as- towards the past and the future (Tulving, 1972, 2001, pect of memory for episodes, and that episodic memory is reconstruc- 2002; Tulving and Markowitsch, 1998). Autobio- tive and thus its key features can be modeled in animal behavioral tasks graphic information contains memories about what that do not involve either autonoetic consciousness or one-trial learning. -

Episodic Memory, Semantic Memory and the Epistemic Asymmetry

1 Remembering past experiences: episodic memory, semantic memory and the epistemic asymmetry Christoph Hoerl forthcoming in K. Michaelian, D. Debus & D. Perrin (eds.): New Directions in the Philosophy of Memory. Routledge. There seems to be a distinctive way in which we can remember events we have experienced ourselves, which differs from the capacity to retain information about events that we can also have when we have not experienced those events ourselves but just learned about them in some other way. Psychologists and increasingly also philosophers have tried to capture this difference in terms of the idea of two different types of memory: episodic memory and semantic memory. Yet, the demarcation between episodic memory and semantic memory remains a contested topic in both disciplines, to the point of there being researchers in each of them who question the usefulness of the distinction between the two concepts.1 In this paper, I outline a new characterization of the difference between episodic memory and semantic memory, which connects that difference to what is sometimes called the ‘epistemic asymmetry’ between the past and the future, or the ‘epistemic arrow’ of time. My proposal will be that episodic memory and semantic memory exemplify the epistemic asymmetry in two different ways, and for somewhat different reasons, and that the way in which 1 The episodic/semantic distinction originates with Tulving (1972), and has been refined by Tulving in a number of other works (Tulving, 1985, 2002; Wheeler, Stuss, & Tulving, 1997). Rival ways of carving up the domain of memories are suggested, for instance, in Bernecker (2010) and Rubin and Umanath (2015). -

Interactions Between Attention and Memory Marvin M Chun and Nicholas B Turk-Browne

Interactions between attention and memory Marvin M Chun and Nicholas B Turk-Browne Attention and memory cannot operate without each other. In form of selective attention to internal representations this review, we discuss two lines of recent evidence that [1,2]. support this interdependence. First, memory has a limited capacity, and thus attention determines what will be Classic psychologists such as William James stated long encoded. Division of attention during encoding prevents the ago that ‘we cannot deny that an object once attended to formation of conscious memories, although the role of attention will remain in the memory, while one inattentively in formation of unconscious memories is more complex. Such allowed to pass will leave no traces behind’ [3]. More memories can be encoded even when there is another recently, leading neuroscientists such as Eric Kandel have concurrent task, but the stimuli that are to be encoded must be stated that one of the most important problems for 21st selected from among other competing stimuli. Second, century neuroscience is to understand how attention memory from past experience guides what should be attended. regulates the processes that stabilize experiential mem- Brain areas that are important for memory, such as the ories [4]. Here, we review studies from the past two years hippocampus and medial temporal lobe structures, are that reveal progress towards understanding the inter- recruited in attention tasks, and memory directly affects frontal- actions between attention and memory in neural systems. parietal networks involved in spatial orienting. Thus, exploring the interactions between attention and memory can provide Attention at encoding new insights into these fundamental topics of cognitive A major question in many people’s minds is how to neuroscience. -

Korsakoff's Syndrome

NEUROPSYCHOLOGY AND NEUROIMAGING OF ALCOHOL USE DISORDER WITH AND WITHOUT KORSAKOFF’S SYNDROME: A BETTER UNDERSTANDING FOR A BETTER TREATMENT Anne Lise PITEL CONFLICT OF INTEREST No conflict of interest to declare. ALCOHOL USE DISORDER (AUD): EPIDEMIOLOGY 10% of French population with disastrous health, psychological, social and professional consequences (Rehm et al. 2011). Alcohol is the cause of 49 000 deaths per year and 18% of the premature deaths in the 35-64 year-old people in France (Guerin et al. 2013). 17% of the admissions in the emergency department in France. Worldwide, alcohol is the third risk factor for morbidity after high blood pressure and tobacco (Moller 2013). Alcohol is the cause of more than 60 diseases (dependence, cirrhosis, psychosis, fetal alcohol syndrome, …) (World Health Organization 2014). Alcohol contributes to the development of more than 200 diseases (cancer, heart disease, pancreatitis, liver disease, …) (Moller 2013). The life expectancy is reduced of 20 years in a man with alcohol dependence (John et al. 2013). The cost related to alcohol or tobacco use disorders is 349 billion euros for Europe, knowing that it is 105 for dementia and 64 for strokes (Effertz et Mann 2013). Tremendous social cost: first cause of hospital admission, sick leave and premature death. ALCOHOL USE DISORDER (AUD): DSM-5 CRITERIA Changes in the concepts: Alcoholism Alcohol dependence (DSM IV) Alcohol Use Disorder (DSM V) A problem pattern of alcohol use, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, manifested by 2 or more of the following in a 12-month period: . Alcohol drunk in larger amounts or for longer time . -

IN PRESS at TRENDS in COGNITIVE SCIENCES Individual

Running Head: INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES AND AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL MEMORY IN PRESS AT TRENDS IN COGNITIVE SCIENCES Individual differences in autobiographical memory Daniela J. Palombo1,2, Signy Sheldon3, & Brian Levine*4,5 1Memory Disorders Research Center & Neuroimaging Research for Veterans Center (NeRVe), VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, USA 2Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, USA 3Department of Psychology, McGill University, Montréal, Canada 4Baycrest Health Sciences, Rotman Research Institute, Toronto, Canada 5Department of Psychology and Medicine (Neurology), University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada *Correspondence: [email protected] (B. Levine). Running Head: INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES AND AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL MEMORY 2 Abstract Although humans have a remarkable capacity to recall a wealth of detail from the past, there are marked inter-individual differences in the quantity and quality of our mnemonic experiences. Such differences in autobiographical memory may appear self-evident, yet there has been little research on this topic. In this review, we synthesize an emerging body of research regarding individual differences in autobiographical memory. We focus on two syndromes that fall at the extreme of the ‘remembering’ dimension, Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM) and Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory (SDAM). We also discuss findings from research on less extreme individual differences in autobiographical memory. This avenue of research is pivotal for a full description of the behavioral and neural substrates of autobiographical memory. Keywords: episodic memory, Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory, Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory Running Head: INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES AND AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL MEMORY 3 Individual Differences in Remembering Humans are capable of retaining a wealth of detail from personal (autobiographical) memories. Yet, the quantity and quality of mnemonic experience differs substantially across individuals. -

The Cognitive Impairment Study (CARES) Trial 1

Journal of Personalized Medicine Article Targeted Nutritional Intervention for Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment: The Cognitive impAiRmEnt Study (CARES) Trial 1 Rebecca Power 1,* , John M. Nolan 1, Alfonso Prado-Cabrero 1 , Robert Coen 2, Warren Roche 1, Tommy Power 1, Alan N. Howard 3 and Ríona Mulcahy 4,5,* 1 Nutrition Research Centre Ireland, School of Health Sciences, Carriganore House, Waterford Institute of Technology West Campus, X91 K0EK Waterford, Ireland; [email protected] (J.M.N.); [email protected] (A.P.-C.); [email protected] (W.R.); [email protected] (T.P.) 2 Mercer’s Institute for Research on Ageing, St. James’s Hospital, D08 NHY1 Dublin, Ireland; [email protected] 3 Howard Foundation, 7 Marfleet Close, Great Shelford, Cambridge CB22 5LA, UK; [email protected] 4 Age-Related Care Unit, Health Service Executive, University Hospital Waterford, Dunmore Road, X91 ER8E Waterford, Ireland 5 Royal College of Surgeons Ireland, 123 Stephen’s Green, Saint Peter’s, D02 YN77 Dublin, Ireland * Correspondence: [email protected] (R.P.); [email protected] (R.M.); Tel.: +353-01-845-505 (R.P.); +353-51-842-509 (R.M.) Received: 31 March 2020; Accepted: 18 May 2020; Published: 25 May 2020 Abstract: Omega-3 fatty acids (!-3FAs), carotenoids, and vitamin E are important constituents of a healthy diet. While they are present in brain tissue, studies have shown that these key nutrients are depleted in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in comparison to cognitively healthy individuals. Therefore, it is likely that these individuals will benefit from targeted nutritional intervention, given that poor nutrition is one of the many modifiable risk factors for MCI. -

Memory Reactivation and Consolidation During Sleep Ken A

Sleep & Memory/Review Memory reactivation and consolidation during sleep Ken A. Paller1 and Joel L. Voss Institute for Neuroscience and Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208-2710, USA Do our memories remain static during sleep, or do they change? We argue here that memory change is not only a natural result of sleep cognition, but further, that such change constitutes a fundamental characteristic of declarative memories. In general, declarative memories change due to retrieval events at various times after initial learning and due to the formation and elaboration of associations with other memories, including memories formed after the initial learning episode. We propose that declarative memories change both during waking and during sleep, and that such change contributes to enhancing binding of the distinct representational components of some memories, and thus to a gradual process of cross-cortical consolidation. As a result of this special form of consolidation, declarative memories can become more cohesive and also more thoroughly integrated with other stored information. Further benefits of this memory reprocessing can include developing complex networks of interrelated memories, aligning memories with long-term strategies and goals, and generating insights based on novel combinations of memory fragments. A variety of research findings are consistent with the hypothesis that cross-cortical consolidation can progress during sleep, although further support is needed, and we suggest some potentially fruitful research directions. Determining how processing during sleep can facilitate memory storage will be an exciting focus of research in the coming years. The idea that memory storage is supported by events that take otherwise intellectually intact. -

Term Episodic Memory in Children with Attention -Deficit /Hyperactivity Disorder

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2005 Long -term episodic memory in children with Attention -Deficit /Hyperactivity Disorder Jeffrey S. Skowronek University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Skowronek, Jeffrey S., "Long -term episodic memory in children with Attention -Deficit /Hyperactivity Disorder" (2005). Doctoral Dissertations. 273. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/273 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LONG-TERM EPISODIC MEMORY IN CHILDREN WITH ATTENTION-DEFICIT/ HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER BY JEFFREY S. SKOWRONEK BA- University of Massachusetts-Lowell, 2000 MA- University of New Hampshire, 2002 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Psychology May, 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3169090 Copyright 2005 by Skowronek, Jeffrey S. All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Sleep's Role in the Consolidation of Emotional Episodic Memories

Current Directions in Psychological Science Sleep’s Role in the Consolidation of 19(5) 290-295 ª The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: Emotional Episodic Memories sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0963721410383978 http://cdps.sagepub.com Jessica D. Payne1 and Elizabeth A. Kensinger2 1 University of Notre Dame and and 2 Boston College Abstract Emotion has a lasting effect on memory, encouraging certain aspects of our experiences to become durable parts of our memory stores. Although emotion exerts its influence at every phase of memory, this review focuses on emotion’s role in the consolidation and transformation of memories over time. Sleep provides ideal conditions for memory consolidation, and recent research demonstrates that manipulating sleep can shed light on the storage and evolution of emotional memories. We provide evidence that sleep enhances the likelihood that select pieces of an experience are stabilized in memory, leading memory for emotional experiences to home in on the aspects of the experience that are most closely tied to the affective response. Keywords affect, amygdala, consolidation, emotion, memory, fMRI, hippocampus, sleep, stabilization, trade-off Episodic memory refers to the long-term retention of contex- consolidated, and affect how events are re-experienced at tually rich representations of past experiences. When we retrieval (see Kensinger, 2009 and McGaugh, 2004 for remember specific events from our past, recalling their spatial reviews). Although emotion’s influence during each of these and temporal context or recollecting perceptual or conceptual phases is critically important, this review focuses on emotion’s details of those events, our memory is considered to be episodic effect on memory consolidation. -

Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory (SDAM)

Neuropsychologia 72 (2015) 105–118 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neuropsychologia journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/neuropsychologia Severely deficient autobiographical memory (SDAM) in healthy adults: A new mnemonic syndrome Daniela J. Palombo a,b,1, Claude Alain a,b, Hedvig Söderlund c, Wayne Khuu a,b, Brian Levine a,b,d,n a Rotman Research Institute, Baycrest Health Sciences, Toronto, ON, Canada M6A 2E1 b Department of Psychology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada M5S 1A1 c Department of Psychology, Uppsala University, Uppsala 751 42, Sweden d Department of Medicine (Neurology), University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada M5S 1A1 article info abstract Article history: Recollection of previously experienced events is a key element of human memory that entails recovery Received 13 January 2015 of spatial, perceptual, and mental state details. While deficits in this capacity in association with brain Received in revised form disease have serious functional consequences, little is known about individual differences in autobio- 7 April 2015 graphical memory (AM) in healthy individuals. Recently, healthy adults with highly superior autobio- Accepted 12 April 2015 graphical capacities have been identified (e.g., LePort, A.K., Mattfeld, A.T., Dickinson-Anson, H., Fallon, J. Available online 17 April 2015 H., Stark, C.E., Kruggel, F., McGaugh, J.L., 2012. Behavioral and neuroanatomical investigation of Highly Keywords: Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM). Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 98(1), 78–92. doi: 10.1016/j. Episodic memory nlm.2012.05.002). Here we report data from three healthy, high functioning adults with the reverse Autobiographical memory pattern: lifelong severely deficient autobiographical memory (SDAM) with otherwise preserved Hippocampus cognitive function.