The Interaction Between Semantic Representation and Episodic Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semantic Memory - Psychology - Oxford Bibliographies

1/16/2019 Semantic Memory - Psychology - Oxford Bibliographies Semantic Memory Michael N. Jones, Johnathan Avery LAST MODIFIED: 15 JANUARY 2019 DOI: 10.1093/OBO/97801998283400231 Introduction Semantic memory refers to our general world knowledge that encompasses memory for concepts, facts, and the meanings of words and other symbolic units that constitute formal communication systems such as language or math. In the classic hierarchical view of memory, declarative memory was subdivided into two independent modules: episodic memory, which is our autobiographical store of individual events, and semantic memory, which is our general store of abstracted knowledge. However, more recent theoretical accounts have greatly reduced the independence of these two memory systems, and episodic memory is typically viewed as a gateway to semantic memory accessed through the process of abstraction. Modern accounts view semantic memory as deeply rooted in sensorimotor experience, abstracted across many episodic memories to highlight the stable characteristics and mute the idiosyncratic ones. A great deal of research in neuroscience has focused on both how the brain creates semantic memories and what brain regions share the responsibility for storage and retrieval of semantic knowledge. These include many classic experiments that studied the behavior of individuals with brain damage and various types of semantic disorders but also more modern studies that employ neuroimaging techniques to study how the brain creates and stores semantic memories. Classically, semantic memory had been treated as a miscellaneous area of study for anything in declarative memory that was not clearly within the realm of episodic memory, and formal models of meaning in memory did not advance at the pace of models of episodic memory. -

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory Richard Topolski ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Sarah R. Daniel ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Introduction methodology for measuring EM largely independent of semantic memory. Episodic memory (EM) is composed of personally experienced events in which ‘the what, where, and when’ Method are essential components while semantic memory is simply composed of accumulated facts about the world (Tulving, Happy, neutral, or sad mood states were induced in 88 2002). A wide variety of tasks have been used to tap students via a 20 minute long viewing of either a stand-up episodic memory including: recalling words from an early comedy routine, a documentary, or holocaust footage. learned list; yes-no recognition of previously presented Immediately following the mood induction, participants common objects or pictures; and free recall of past personal engaged in eight interactive tasks which involved both experiences. These tasks are used to evaluate episodic familiar objects (pennies and paperclips) and novel memory because in order to know which words, pictures, or geometric forms created by bending paper clips with blue experiences to retrieve, some contextual (episodic) beads into unique shapes, (Rock, Schreilber, and Ro, 1994). information must first be accessed (Mayes & Roberts, A four-item force-choice recognition test for the novel 2001). While all of these measures seem to share this geometric forms was employed, with the task name serving contextual component, none adequately examines the as the retrieval cue. -

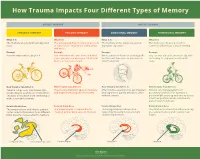

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Episodic Memory-From Brain to Mind

HIPPOCAMPUS 16:691–703 (2006) Episodic Memory—From Brain to Mind Janina Ferbinteanu,* Pamela J. Kennedy, and Matthew L. Shapiro ABSTRACT: Neuronal mechanisms of episodic memory, the conscious by the rapid formation of relational representations of recollection of autobiographical events, are largely unknown because highly processed sensory information that are used electrophysiological studies in humans are conducted only in excep- tional circumstances. Unit recording studies in animals are thus crucial flexibly and are not necessarily expressed through overt for understanding the neurophysiological substrate that enables people motor behavior. Episodic memory is also sensitive to to remember their individual past. Two features of episodic memory— lesions of the prefrontal cortex (Wheeler et al., 1995; autonoetic consciousness, the self-aware ability to \travel through Nyberg et al., 2000; Burgess et al., 2002; Wheeler time", and one-trial learning, the acquisition of information in one and Stuss, 2003), develops later in an individual’s life, occurrence of the event—raise important questions about the validity of animal models and the ability of unit recording studies to capture essen- encodes events within a personal framework, and pos- tial aspects of memory for episodes. We argue that autonoetic experi- sesses a temporal dimension because it is oriented ence is a feature of human consciousness rather than an obligatory as- towards the past and the future (Tulving, 1972, 2001, pect of memory for episodes, and that episodic memory is reconstruc- 2002; Tulving and Markowitsch, 1998). Autobio- tive and thus its key features can be modeled in animal behavioral tasks graphic information contains memories about what that do not involve either autonoetic consciousness or one-trial learning. -

PSYC20006 Notes

PSYC20006 BIOLOGICAL PSYCHOLOGY PSYC20006 1 COGNITIVE THEORIES OF MEMORY Procedural Memory: The storage of skills & procedures, key in motor performance. It involves memory systems that are independent of the hippocampal formation, in particular, the cerebellum, basal ganglia, cortical motor sites. Doesn't involve mesial-temporal function, basal forebrain or diencephalon. Declarative memory: Accumulation of facts/data from learning experiences. • Associated with encoding & maintaining information, which comes from higher systems in the brain that have processed the information • Information is then passed to hippocampal formation, which does the encoding for elaboration & retention. Hippocampus is in charge of structuring our memories in a relational way so everything relating to the same topic is organized within the same network. This is also how memories are retrieved. Activation of 1 piece of information will link up the whole network of related pieces of information. Memories are placed into an already exiting framework, and so memory activation can be independent of the environment. MODELS OF MEMORY Serial models of Memory include the Atkinson-Shiffrin Model, Levels of Processing Model & Tulving’s Model — all suggest that memory is processed in a sequential way. A parallel model of memory, the Parallel Distributed Processing Model, is one which suggests types of memories are processed independently. Atkinson-Shiffrin Model First starts as Sensory Memory (visual / auditory). If nothing is done with it, fades very quickly but if you pay attention to it, it will move into working memory. Working Memory contains both new information & from long-term memory. If it goes through an encoding process, it will be in long-term memory. -

Semantic Priming in Schizophrenia: a Review and Synthesis

Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (2002), 8, 699–720. Copyright © 2002 INS. Published by Cambridge University Press. Printed in the USA. DOI: 10.1017.S1355617702801357 CRITICAL REVIEW Semantic priming in schizophrenia: A review and synthesis MICHAEL J. MINZENBERG,1 BETH A. OBER,2 and SOPHIA VINOGRADOV1 1Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco and Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco, California 2Department of Human and Community Development, University of California, Davis and Department of Veterans Affairs Northern California Health Care System, Martinez, California (Received October 9, 2000; Revised June 4, 2001; Accepted June 5, 2001) Abstract In this paper, we present a review of semantic priming experiments in schizophrenia. Semantic priming paradigms show utility in assessing the role of deficits in semantic memory network access in the pathology of schizophrenia. The studies are placed in the context of current models of information processing. In this review we include all English-language reports (from peer-reviewed journals) of single-word semantic priming studies involving participants with schizophrenia. The studies to date show schizophrenic patients to exhibit variable semantic priming effects under automatic processing conditions, and consistent impairments under controlled0attentional conditions. We also describe associations with other neurocognitive dysfunction, neurochemical and electrophysiological disturbances, and clinical manifestations (such as thought disorder). (JINS, 2002, 8, 699–720.) Keywords: Semantic priming, Schizophrenia, Semantic memory, Language, Information processing INTRODUCTION Semantic Memory and Spreading Schizophrenia is primarily a disorder of thinking and lan- Activation Network Models guage. Indeed, investigators have suggested that a defect in All information processing models posit the existence of a language information processing may be pathognomonic of long-term memory system. -

Memory & Cognition

/ Memory & Cognition Volume 47 · Number 4 · May 2019 Special Issue: Recognizing Five Decades of Cumulative The role of control processes in temporal Progress in Understanding Human Memory and semantic contiguity and its Control Processes Inspired by Atkinson M.K. Healey · M.G. Uitvlugt 719 and Shiffrin (1968) Auditory distraction does more than disrupt rehearsal Guest Editors: Kenneth J. Malmberg· processes in children's serial recall Jeroen G. W. Raaijmakers ·Richard M. Shiffrin A.M. AuBuchon · C.l. McGill · E.M. Elliott 738 50 years of research sparked by Atkinson The effect of working memory maintenance and Shiffrin (1968) on long-term memory K.J. Malmberg · J.G.W. Raaijmakers · R.M. Shiffrin 561 J.K. Hartshorne· T. Makovski 749 · From ·short-term store to multicomponent working List-strength effects in older adults in recognition memory: The role of the modal model and free recall A.D. Baddeley · G.J. Hitch · R.J. Allen 575 L. Sahakyan 764 Central tendency representation and exemplar Verbal and spatial acquisition as a function of distributed matching in visual short-term memory practice and code-specific interference C. Dube 589 A.P. Young· A.F. Healy· M. Jones· L.E. Bourne Jr. 779 Item repetition and retrieval processes in cued recall: Dissociating visuo-spatial and verbal working memory: Analysis of recall-latency distributions It's all in the features Y. Jang · H. Lee 792 ~1 . Poirier· J.M. Yearsley · J. Saint-Aubin· C. Fortin· G. Gallant · D. Guitard 603 Testing the primary and convergent retrieval model of recall: Recall practice produces faster recall Interpolated retrieval effects on list isolation: success but also faster recall failure IndiYiduaLdifferences in working memory capacity W.J. -

Models of Memory

To be published in H. Pashler & D. Medin (Eds.), Stevens’ Handbook of Experimental Psychology, Third Edition, Volume 2: Memory and Cognitive Processes. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. MODELS OF MEMORY Jeroen G.W. Raaijmakers Richard M. Shiffrin University of Amsterdam Indiana University Introduction Sciences tend to evolve in a direction that introduces greater emphasis on formal theorizing. Psychology generally, and the study of memory in particular, have followed this prescription: The memory field has seen a continuing introduction of mathematical and formal computer simulation models, today reaching the point where modeling is an integral part of the field rather than an esoteric newcomer. Thus anything resembling a comprehensive treatment of memory models would in effect turn into a review of the field of memory research, and considerably exceed the scope of this chapter. We shall deal with this problem by covering selected approaches that introduce some of the main themes that have characterized model development. This selective coverage will emphasize our own work perhaps somewhat more than would have been the case for other authors, but we are far more familiar with our models than some of the alternatives, and we believe they provide good examples of the themes that we wish to highlight. The earliest attempts to apply mathematical modeling to memory probably date back to the late 19th century when pioneers such as Ebbinghaus and Thorndike started to collect empirical data on learning and memory. Given the obvious regularities of learning and forgetting curves, it is not surprising that the question was asked whether these regularities could be captured by mathematical functions. -

Okami Study Guide: Chapter 8 1

Okami Study Guide: Chapter 8 1 Chapter in Review 1. Memory may be defined as a group of mechanisms and systems that encode, store, and retrieve information. The modal model of memory describes three stages and stores in the memory process: sensory memory, short-term memory (STM), and long- term memory (LTM). 2. Sensory memory very briefly stores fleeing sensory impressions for further processing in STM and LTM. Sensory memory is divided into two categories: iconic store, which stores fleeting visual impressions; and echoic store, which stores fleeting auditory impressions. In addition to storing sensory impressions for further processing, sensory memory allows us to perceive the world as a continuous stream of events instead of a series of “snapshots.” 3. When you consciously or unconsciously decide to pay attention to specific pieces of information in sensory memory, the information is transferred into short-term memory. The duration and capacity of STM are limited. In general, information can remain in STM for no longer than 20 seconds unless maintenance rehearsal takes place, and no more than 4 single items or chunks of information can be held in STM at any one time. A chunk is any grouping of items that are strongly associated with one another. 4. Long-term memory (LTM) is theoretically limitless and relatively permanent. Information moves from STM to LTM when it is encoded in one of three ways: through sound (acoustic encoding), imagery (visual encoding), or meaning (semantic encoding). Encoding in STM tends to be primarily acoustic, secondarily visual, and much less often semantic. However, encoding in LTM is most effective if it is semantic. -

Episodic Memory, Semantic Memory and the Epistemic Asymmetry

1 Remembering past experiences: episodic memory, semantic memory and the epistemic asymmetry Christoph Hoerl forthcoming in K. Michaelian, D. Debus & D. Perrin (eds.): New Directions in the Philosophy of Memory. Routledge. There seems to be a distinctive way in which we can remember events we have experienced ourselves, which differs from the capacity to retain information about events that we can also have when we have not experienced those events ourselves but just learned about them in some other way. Psychologists and increasingly also philosophers have tried to capture this difference in terms of the idea of two different types of memory: episodic memory and semantic memory. Yet, the demarcation between episodic memory and semantic memory remains a contested topic in both disciplines, to the point of there being researchers in each of them who question the usefulness of the distinction between the two concepts.1 In this paper, I outline a new characterization of the difference between episodic memory and semantic memory, which connects that difference to what is sometimes called the ‘epistemic asymmetry’ between the past and the future, or the ‘epistemic arrow’ of time. My proposal will be that episodic memory and semantic memory exemplify the epistemic asymmetry in two different ways, and for somewhat different reasons, and that the way in which 1 The episodic/semantic distinction originates with Tulving (1972), and has been refined by Tulving in a number of other works (Tulving, 1985, 2002; Wheeler, Stuss, & Tulving, 1997). Rival ways of carving up the domain of memories are suggested, for instance, in Bernecker (2010) and Rubin and Umanath (2015). -

Long Term Memory & Amnesia

Previous theories of Amnesia: encoding faliure (consolidation) rapid forgetting and Amnesic Patients typically retain old procedural retrieval failure (retroactive/proactive information and are reasonably good at learning interference, Underwood; McGeoch) new procedural skills (H.M and mirror writing) Important Current Theory: Contextual Amnesia & the Brain Linked to Conditioning: eyeblink with puf of air leads to Memory Theory (Ryan et al. 2000) medial temporal lobe and diencephalic conditioned response. Patients with amnesia impairment in integrating of binding region, including mamillary bodies and typically acquire this. contextual/relational features of memory. thalamus. Priming: Improvement or bias in performance The medial temporal lobe and hippocampus resulting from prior, supraliminal presentation of Procedural Memory are proposed to bind events to the contexts stimuli. Tulving et al. (1982) primed participants Often relatively automatic processes in which they occur. This bypasses the with a list of words and then showed them letters (requiring little attention) allowing for declarative vs procedural distinction. And (cued-recall). Recall was better for words behavioural responses to there is reasonable support for this theory presented earlier. Amnesic patients are relatively environmental cues. (Channon, Shanks et al 2006.) normal on these tasks. Long-Term Memory & Amnesia Temporary storage of information with rapid Short-Term Memory decay and sensitivity to interference. Supported by studies of recency efect (Murdock, Postman), which is taken as evidence of short Long-Term Memory Mediates declarative Double Dissociation?! but not non-declarative (procedural) memory. term memory store. Also by studies supporting subvocal speech (Baddeley, 1966) However, studies have provided evidence of Declarative Memory This is knowledge STM link with LTM retrieved by explicit, deliberate recollection. -

Encoding and Retrieval from Long-Term Memory

SMITMC05_0131825089.QXD 3/29/06 12:49 AM Page 192 REVISED PAGES CHAPTER 5 Encoding and Retrieval from Long-Term Memory Learning Objectives 1. The Nature of Long-Term Memory 3.3. Cues for Retrieval 1.1. The Forms of Long-Term Memory 3.4. The Second Time Around: Recognizing 1.2. The Power of Memory: The Story of H.M. Stimuli by Recollection and Familiarity 1.3. Multiple Systems for Long-Term DEBATE: “Remembering,” “Knowing,” and Learning and Remembering the Medial Temporal Lobes 2. Encoding: How Episodic Memories are 3.5. Misremembering the Past Formed 3.5.1. Bias 2.1. The Importance of Attention 3.5.2. Misattribution A CLOSER LOOK: Transfer Appropriate 3.5.3. Suggestion Processing 4. The Encoding Was Successful, But I Still 2.2. Levels of Processing and Elaborative Can’t Remember Encoding 4.1. Ebbinghaus’s Forgetting Function 2.2.1. Levels-of-Processing Theory: 4.2. Forgetting and Competition Argument and Limitations 4.2.1. Retroactive and Proactive 2.2.2. The Brain, Semantic Elabora- Interference tion, and Episodic Encoding 4.2.2. Blocking and Suppression 2.3. Enhancers of Encoding: Generation and 5. Nondeclarative Memory Systems Spacing 5.1. Priming 2.3.1. The Generation Effect 5.1.1. Perceptual Priming 2.3.2. The Spacing Effect 5.1.2. Conceptual Priming 2.4. Episodic Encoding, Binding, and the 5.2. Beyond Priming: Other Forms of Non- Medial Temporal Lobe declarative Memory 2.5. Consolidation: The Fixing of Memory 5.2.1. Skill Learning 3. Retrieval: How We Recall the Past from 5.2.2.