(HSAM): Memory Distortion Paradigms and Individual Differences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

Psychogenic and Organic Amnesia. a Multidimensional Assessment of Clinical, Neuroradiological, Neuropsychological and Psychopathological Features

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 53–64 53 IOS Press Psychogenic and organic amnesia. A multidimensional assessment of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological features Laura Serraa,∗, Lucia Faddaa,b, Ivana Buccionea, Carlo Caltagironea,b and Giovanni A. Carlesimoa,b aFondazione IRCCS Santa Lucia, Roma, Italy bClinica Neurologica, Universita` Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy Abstract. Psychogenic amnesia is a complex disorder characterised by a wide variety of symptoms. Consequently, in a number of cases it is difficult distinguish it from organic memory impairment. The present study reports a new case of global psychogenic amnesia compared with two patients with amnesia underlain by organic brain damage. Our aim was to identify features useful for distinguishing between psychogenic and organic forms of memory impairment. The findings show the usefulness of a multidimensional evaluation of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological aspects, to provide convergent findings useful for differentiating the two forms of memory disorder. Keywords: Amnesia, psychogenic origin, organic origin 1. Introduction ness of the self – and a period of wandering. According to Kopelman [33], there are three main predisposing Psychogenic or dissociative amnesia (DSM-IV- factors for global psychogenic amnesia: i) a history of TR) [1] is a clinical syndrome characterised by a mem- transient, organic amnesia due to epilepsy [52], head ory disorder of nonorganic origin. Following Kopel- injury [4] or alcoholic blackouts [20]; ii) a history of man [31,33], psychogenic amnesia can either be sit- psychiatric disorders such as depressed mood, and iii) uation specific or global. Situation specific amnesia a severe precipitating stress, such as marital or emo- refers to memory loss for a particular incident or part tional discord [23], bereavement [49], financial prob- of an incident and can arise in a variety of circum- lems [23] or war [21,48]. -

Mnemonics in a Mnutshell: 32 Aids to Psychiatric Diagnosis

Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis Clever, irreverent, or amusing, a mnemonic you remember is a lifelong learning tool ® Dowden Health Media rom SIG: E CAPS to CAGE and WWHHHHIMPS, mnemonics help practitioners and trainees recall Fimportant lists (suchCopyright as criteriaFor for depression,personal use only screening questions for alcoholism, or life-threatening causes of delirium, respectively). Mnemonics’ effi cacy rests on the principle that grouped information is easi- er to remember than individual points of data. Not everyone loves mnemonics, but recollecting diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice and research, on board examinations, and for insurance reimbursement. Thus, tools that assist in recalling di- agnostic criteria have a role in psychiatric practice and IMAGES teaching. JUPITER In this article, we present 32 mnemonics to help cli- © nicians diagnose: • affective disorders (Box 1, page 28)1,2 Jason P. Caplan, MD Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry • anxiety disorders (Box 2, page 29)3-6 Creighton University School of Medicine 7,8 • medication adverse effects (Box 3, page 29) Omaha, NE • personality disorders (Box 4, page 30)9-11 Chief of psychiatry • addiction disorders (Box 5, page 32)12,13 St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center Phoenix, AZ • causes of delirium (Box 6, page 32).14 We also discuss how mnemonics improve one’s Theodore A. Stern, MD Professor of psychiatry memory, based on the principles of learning theory. Harvard Medical School Chief, psychiatric consultation service Massachusetts General Hospital How mnemonics work Boston, MA A mnemonic—from the Greek word “mnemonikos” (“of memory”)—links new data with previously learned information. -

Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: the Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity

brain sciences Article Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: The Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity Vanesa Hidalgo 1,* , Carolina Villada 2 and Alicia Salvador 3 1 Department of Psychology and Sociology, Area of Psychobiology, University of Zaragoza, 44003 Teruel, Spain 2 Department of Psychology, Division of Health Sciences, University of Guanajuato, Leon 37670, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychobiology and IDOCAL, University of Valencia, 46010 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-978-645-346 Received: 11 October 2020; Accepted: 15 December 2020; Published: 16 December 2020 Abstract: In contrast to the large body of research on the effects of stress-induced cortisol on memory consolidation in young people, far less attention has been devoted to understanding the effects of stress-induced testosterone on this memory phase. This study examined the psychobiological (i.e., anxiety, cortisol, and testosterone) response to the Maastricht Acute Stress Test and its impact on free recall and recognition for emotional and neutral material. Thirty-seven healthy young men and women were exposed to a stress (MAST) or control task post-encoding, and 24 h later, they had to recall the material previously learned. Results indicated that the MAST increased anxiety and cortisol levels, but it did not significantly change the testosterone levels. Post-encoding MAST did not affect memory consolidation for emotional and neutral pictures. Interestingly, however, cortisol reactivity was negatively related to free recall for negative low-arousal pictures, whereas testosterone reactivity was positively related to free recall for negative-high arousal and total pictures. -

Reducing False Memories Chad S

MacLeod and MacDonald – The Stroop effect and attention Review 17 Dunbar, K.N. and MacLeod, C.M. (1984) A horse race of a different 28 Carter, C.S. et al. (2000) Parsing executive processes: strategic versus color: Stroop interference patterns with transformed words. J. Exp. evaluative functions of the anterior cingulate cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 10, 622–639 Sci. U. S. A. 97, 1944–1948 18 Fraisse, P. (1969) Why is naming longer than reading? Acta Psychol. 29 Derbyshire, S.W.G. et al. (1998) Pain and Stroop interference activate 30, 96–103 separate processing modules in anterior cingulate. Exp. Brain Res. 19 Kolers, P.A. (1975) Memorial consequences of automatized encoding. 118, 52–60 J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Learn. Mem. 1, 689–701 30 Bush, G. et al. (2000) Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior 20 Tzelgov, J. et al. (1992) Controlling Stroop effects by manipulating cingulate cortex. Trends Cognit. Sci. 4, 215–222 expectations for color words. Mem. Cognit. 20, 727–735 31 Corbetta, M. et al. (1991) Selective and divided attention during visual 21 Duncan-Johnson, C.C. (1981) P300 latency: a new metric of discriminations of shape, color, and speed: functional anatomy by information processing. Psychophysiology 18, 207–215 positron emission tomography. J. Neurosci. 11, 2383–2402 22 Duncan-Johnson, C.C. and Kopell, B.S. (1981) The Stroop effect: brain 32 Petersen, S.E. et al. (1988) Positron emission tomographic studies potentials localize the source of interference. Science 214, 938–940 of the cortical anatomy of single-word processing. Nature 23 Bench, C.J. -

Pleasantness Bias in Flashbulb Memories: Positive and Negative Flashbulb Memories of the Fall of the Berlin Wall Among East and West Germans

Memory & Cognition 2007, 35 (3), 565-577 Pleasantness bias in flashbulb memories: Positive and negative flashbulb memories of the fall of the Berlin Wall among East and West Germans ANNETTE BOHN AND DORTHE BERNTSEN Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark Flashbulb memories for the fall of the Berlin Wall were examined among 103 East and West Germans who considered the event as either highly positive or highly negative. The participants in the positive group rated their memories higher on measures of reliving and sensory imagery, whereas their memory for facts was less accurate than that of the participants in the negative group. The participants in the negative group had higher ratings on amount of consequences but had talked less about the event and considered it less central to their personal and national identity than did the participants in the positive group. In both groups, rehearsal and the centrality of the memory to the person’s identity and life story correlated positively with memory qualities. The results suggest that positive and negative emotions have different effects on the processing and long-term reten- tion of flashbulb memories. On Thursday, November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell Wall, and how well do they remember factual details in re- after having divided East and West Germany for 28 years. lation to the event? These are the chief questions raised in On that day at 6:57 p.m., Günther Schabowski, a leading the present article. By addressing these questions, we wish member of the ruling communist party in East Germany, to investigate whether positive versus negative affect is as- had casually announced to a stunned audience during a sociated with different qualities of flashbulb memories. -

What Is It Like to Be Confabulating?

What is it like to be Confabulating? Sahba Besharati, Aikaterini Fotopoulou and Michael D. Kopelman Kings College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London UK Different kinds of confabulations may arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. This chapter first offers conceptual distinctions between spontaneous and momentary (“provoked”) confabulations, as well as between these types of confabulation and other kinds of false memories. The chapter then reviews current explanatory theories, emphasizing that both neurocognitive and motivational factors account for the content of confabulations. We place particular emphasis on a general model of confabulation that considers cognitive dysfunctions in memory and executive functioning in parallel with social and emotional factors. It is argued that all these dimensions need to be taken into account for a phenomenologically rich description of confabulation. The role of the motivated content of confabulation and the subjective experience of the patient are particularly relevant in effective management and rehabilitation strategies. Finally, we discuss a case example in order to illustrate how seemingly meaningless false memories are actually meaningful if placed in the context of the patient’s own perspective and autobiographical memory. Key words: Confabulation; False memory; Motivation; Self; Rehabilitation. 1 Memory is often subject to errors of omission and commission such that recollection includes instances of forgetting, or distorting past experience. The study of pathological forms of exaggerated memory distortion has provided useful insights into the mechanisms of normal reconstructive remembering (Johnson, 1991; Kopelman, 1999; Schacter, Norman & Kotstall, 1998). An extreme form of pathological memory distortion is confabulation. Different variants of confabulation are found to arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. -

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory Richard Topolski ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Sarah R. Daniel ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Introduction methodology for measuring EM largely independent of semantic memory. Episodic memory (EM) is composed of personally experienced events in which ‘the what, where, and when’ Method are essential components while semantic memory is simply composed of accumulated facts about the world (Tulving, Happy, neutral, or sad mood states were induced in 88 2002). A wide variety of tasks have been used to tap students via a 20 minute long viewing of either a stand-up episodic memory including: recalling words from an early comedy routine, a documentary, or holocaust footage. learned list; yes-no recognition of previously presented Immediately following the mood induction, participants common objects or pictures; and free recall of past personal engaged in eight interactive tasks which involved both experiences. These tasks are used to evaluate episodic familiar objects (pennies and paperclips) and novel memory because in order to know which words, pictures, or geometric forms created by bending paper clips with blue experiences to retrieve, some contextual (episodic) beads into unique shapes, (Rock, Schreilber, and Ro, 1994). information must first be accessed (Mayes & Roberts, A four-item force-choice recognition test for the novel 2001). While all of these measures seem to share this geometric forms was employed, with the task name serving contextual component, none adequately examines the as the retrieval cue. -

Examining the Effect of Interference on Short-Term Memory Recall of Arabic Abstract and Concrete Words Using Free, Cued, and Serial Recall Paradigms

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 6 No. 6; December 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Examining the Effect of Interference on Short-term Memory Recall of Arabic Abstract and Concrete Words Using Free, Cued, and Serial Recall Paradigms Ahmed Mohammed Saleh Alduais (Corresponding author) Department of Linguistics, Social Sciences Institute Ankara University, 06100 Sıhhiye, Ankara, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] Yasir Saad Almukhaizeem Department of Linguistics and Translation, College of Languages and Translation King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.7 Received: 29/05/2015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.7 Accepted: 18/08/2015 The research is financed by Research Centre in the College of Languages and Translation Studies and the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Abstract Purpose: To see if there is a correlation between interference and short-term memory recall and to examine interference as a factor affecting memory recalling of Arabic and abstract words through free, cued, and serial recall tasks. Method: Four groups of undergraduates in King Saud University, Saudi Arabia participated in this study. The first group consisted of 9 undergraduates who were trained to perform three types of recall for 20 Arabic abstract and concrete words. The second, third and fourth groups consisted of 27 undergraduates where each group was trained only to perform one recall type: free recall, cued recall and serial recall respectively. -

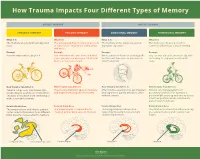

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Emotionally Charged Autobiographical Memories Across the Life Span: the Recall of Happy, Sad, Traumatic, and Involuntary Memories

Psychology and Aging Copyright 2002 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2002, Vol. 17, No. 4, 636–652 0882-7974/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.636 Emotionally Charged Autobiographical Memories Across the Life Span: The Recall of Happy, Sad, Traumatic, and Involuntary Memories Dorthe Berntsen David C. Rubin University of Aarhus Duke University A sample of 1,241 respondents between 20 and 93 years old were asked their age in their happiest, saddest, most traumatic, most important memory, and most recent involuntary memory. For older respondents, there was a clear bump in the 20s for the most important and happiest memories. In contrast, saddest and most traumatic memories showed a monotonically decreasing retention function. Happy involuntary memories were over twice as common as unhappy ones, and only happy involuntary memories showed a bump in the 20s. Life scripts favoring positive events in young adulthood can account for the findings. Standard accounts of the bump need to be modified, for example, by repression or reduced rehearsal of negative events due to life change or social censure. Many studies have examined the distribution of autobiographi- (1885/1964) drew attention to conscious memories that arise un- cal memories across the life span. No studies have examined intendedly and treated them as one of three distinct classes of whether this distribution is different for different classes of emo- memory, but did not study them himself. In his well-known tional memories. Here, we compare the event ages of people’s textbook, Miller (1962/1974) opened his chapter on memory by most important, happiest, saddest, and most traumatic memories quoting Marcel Proust’s description of how the taste of a Made- and most recent involuntary memory to explore whether different leine cookie unintendedly brought to his mind a long-forgotten kinds of emotional memories follow similar patterns of retention. -

Cognitive Psychology

COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PSYCH 126 Acknowledgements College of the Canyons would like to extend appreciation to the following people and organizations for allowing this textbook to be created: California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office Chancellor Diane Van Hook Santa Clarita Community College District College of the Canyons Distance Learning Office In providing content for this textbook, the following professionals were invaluable: Mehgan Andrade, who was the major contributor and compiler of this work and Neil Walker, without whose help the book could not have been completed. Special Thank You to Trudi Radtke for editing, formatting, readability, and aesthetics. The contents of this textbook were developed under the Title V grant from the Department of Education (Award #P031S140092). However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Unless otherwise noted, the content in this textbook is licensed under CC BY 4.0 Table of Contents Psychology .................................................................................................................................................... 1 126 ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1 - History of Cognitive Psychology ............................................................................................. 7 Definition of Cognitive Psychology