Memory and Metamemory: a Study of the Feeling-Of-Knowing Phenomenon in Amnesic Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of Emotional Arousal 1 Running Head

Effect of Emotional Arousal 1 Running Head: THE EFFECT OF EMOTIONAL AROUSAL ON RECALL The Effect of Emotional Arousal and Valence on Memory Recall 500181765 Bangor University Group 14, Thursday Afternoon Effect of Emotional Arousal 2 Abstract This study examined the effect of emotion on memory when recalling positive, negative and neutral events. Four hundred and fourteen participants aged over 18 years were asked to read stories that differed in emotional arousal and valence, and then performed a spatial distraction task before they were asked to recall the details of the stories. Afterwards, participants rated the stories on how emotional they found them, from ‘Very Negative’ to ‘Very Positive’. It was found that the emotional stories were remembered significantly better than the neutral story; however there was no significant difference in recall when a negative mood was induced versus a positive mood. Therefore this research suggests that emotional valence does not affect recall but emotional arousal affects recall to a large extent. Effect of Emotional Arousal 3 Emotional arousal has often been found to influence an individual’s recall of past events. It has been documented that highly emotional autobiographical memories tend to be remembered in better detail than neutral events in a person’s life. Structures involved in memory and emotions, the hippocampus and amygdala respectively, are joined in the limbic system within the brain. Therefore, it would seem true that emotions and memory are linked. Many studies have investigated this topic, finding that emotional arousal increases recall. For instance, Kensinger and Corkin (2003) found that individuals remember emotionally arousing words (such as swear words) more than they remember neutral words. -

Implicit Memory in Amnesic Patients: When Is Auditory Priming Spared?

Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (1995), 1, 434-442. Copyright © 1995 INS. Published by Cambridge University Press. Printed in the USA. Implicit memory in amnesic patients: When is auditory priming spared? DANIEL L. SCHACTER1 AND BARBARA CHURCH2 1 Harvard University and Memory Disorders Research Center, Veterans Administration Medical Center, Cambridge, MA 02138 2 University of Illinois, Champaign, IL 61820 (RECEIVED February 16, 1995; ACCEPTED March 2, 1995) Abstract Amnesic patients often exhibit spared priming effects on implicit memory tests despite poor explicit memory. In previous research, we found normal auditory priming in amnesic patients on a task in which the magnitude of priming in control subjects was independent of whether speaker's voice was same or different at study and test, and found impaired voice-specific priming on a task in which priming in control subjects is higher when speaker's voice is the same at study and test than when it is different. The present experiments provide further evidence of spared auditory priming in amnesia, demonstrate that normal priming effects are not an artifact of low levels of baseline performance, and provide suggestive evidence that amnesic patients can exhibit voice-specific priming when experimental conditions do not require them to interactively bind together word and voice information. (JINS, 1995, 7, 434-442.) Keywords: Amnesia, Priming, Implicit memory Introduction jects heard a list of spoken words and judged either the category to which each word belongs (semantic encoding It is well known that amnesic patients can exhibit robust task) or the pitch of the speaker's voice (nonsemantic en- implicit memory despite impaired explicit memory. -

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky and Robert A. Bjork Introduction Memory has been of interest to scholars and laypeople alike for over 2,000 years. In a rather gruesome example from antiquity, Cicero tells the story of Simonides (557– 468 BC), who discovered the method of loci, which is a powerful mental mnemonic for enhancing one’s memory. Simonides was at a banquet of a nobleman, Scopas. To honor him, Simonides sang a poem, but to Scopas’s chagrin, the poem also honored two young men, Castor and Pollux. Being upset, Scopas told Simonides that he was to receive only half his wage. Simonides was later called from the banquet, and legend has it that the banquet room collapsed, and all those inside were crushed. To help bereaved families identify the victims, Simonides reportedly was able to name every- one according to the place where they sat at the table, which gave him the idea that order brings strength to our memories and that to employ this ability people “should choose localities, then form mental images of things they wanted to store in their memory, and place these in the localities” (Cicero, 2001). Tis example highlights an early discovery that has had important applied impli- cations for improving the functioning of memory (see, e.g., Yates, 1997). Memory theory was soon to follow. Aristotle (385–322 BC) claimed that memory arises from three processes: Events are associated (1) through their relative similarity or (2) rela- tive dissimilarity and (3) when they co-occur together in space and time. -

Mnemonics in a Mnutshell: 32 Aids to Psychiatric Diagnosis

Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis Clever, irreverent, or amusing, a mnemonic you remember is a lifelong learning tool ® Dowden Health Media rom SIG: E CAPS to CAGE and WWHHHHIMPS, mnemonics help practitioners and trainees recall Fimportant lists (suchCopyright as criteriaFor for depression,personal use only screening questions for alcoholism, or life-threatening causes of delirium, respectively). Mnemonics’ effi cacy rests on the principle that grouped information is easi- er to remember than individual points of data. Not everyone loves mnemonics, but recollecting diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice and research, on board examinations, and for insurance reimbursement. Thus, tools that assist in recalling di- agnostic criteria have a role in psychiatric practice and IMAGES teaching. JUPITER In this article, we present 32 mnemonics to help cli- © nicians diagnose: • affective disorders (Box 1, page 28)1,2 Jason P. Caplan, MD Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry • anxiety disorders (Box 2, page 29)3-6 Creighton University School of Medicine 7,8 • medication adverse effects (Box 3, page 29) Omaha, NE • personality disorders (Box 4, page 30)9-11 Chief of psychiatry • addiction disorders (Box 5, page 32)12,13 St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center Phoenix, AZ • causes of delirium (Box 6, page 32).14 We also discuss how mnemonics improve one’s Theodore A. Stern, MD Professor of psychiatry memory, based on the principles of learning theory. Harvard Medical School Chief, psychiatric consultation service Massachusetts General Hospital How mnemonics work Boston, MA A mnemonic—from the Greek word “mnemonikos” (“of memory”)—links new data with previously learned information. -

Working Memory and Cued Recall Max V

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2016 Working memory and cued recall Max V. Fey 8602950 Karen Naufel Georgia Southern University Lawrence Locker Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Fey, Max V. 8602950; Naufel, Karen; and Locker, Lawrence, "Working memory and cued recall" (2016). University Honors Program Theses. 220. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/220 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Working Memory and Cued Recall Working Memory and Cued Recall An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Psychology. By Maximilian Fey Under the mentorship of Dr. Karen Naufel ABSTRACT Previous research has found that individuals with high working memory have greater recall capabilities than those with low working memory (Unsworth, Spiller, & Brewers, 2012). Research did not test the extent to which cues affect one’s recall ability in relation to working memory. The present study will examine this issue. Participants completed a working memory measure. Then, they were provided with cued recall tasks whereby they recalled Facebook friends. The cues varied to be no cues, ambiguous cues high in imageability, and cues directly related to Facebook. The results showed that there was no difference between individual’s ability to recall their Facebook friends and their working memory scores. -

Types of Memory and Models of Memory

Inf1: Intro to Cognive Science Types of memory and models of memory Alyssa Alcorn, Helen Pain and Henry Thompson March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 1 1. In the lecture today A review of short-term memory, and how much stuff fits in there anyway 1. Whether or not the number 7 is magic 2. Working memory 3. The Baddeley-Hitch model of memory hEp://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/s/ short_term_memory.asp March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 2 2. Review of Short-Term Memory (STM) Short-term memory (STM) is responsible for storing small amounts of material over short periods of Nme A short Nme really means a SHORT Nme-- up to several seconds. Anything remembered for longer than this Nme is classified as long-term memory and involves different systems and processes. !!! Note that this is different that what we mean mean by short- term memory in everyday speech. If someone cannot remember what you told them five minutes ago, this is actually a problem with long-term memory. While much STM research discusses verbal or visuo-spaal informaon, the disNncNon of short vs. long-term applies to other types of sNmuli as well. 3/21/12 Intro to Cognitive Science 3 3. Memory span and magic numbers Amount of informaon varies with individual’s memory span = longest number of items (e.g. digits) that can be immediately repeated back in correct order. Classic research by George Miller (1956) described the apparent limits of short-term memory span in one of the most-cited papers in all of psychology. -

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory Richard Topolski ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Sarah R. Daniel ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Introduction methodology for measuring EM largely independent of semantic memory. Episodic memory (EM) is composed of personally experienced events in which ‘the what, where, and when’ Method are essential components while semantic memory is simply composed of accumulated facts about the world (Tulving, Happy, neutral, or sad mood states were induced in 88 2002). A wide variety of tasks have been used to tap students via a 20 minute long viewing of either a stand-up episodic memory including: recalling words from an early comedy routine, a documentary, or holocaust footage. learned list; yes-no recognition of previously presented Immediately following the mood induction, participants common objects or pictures; and free recall of past personal engaged in eight interactive tasks which involved both experiences. These tasks are used to evaluate episodic familiar objects (pennies and paperclips) and novel memory because in order to know which words, pictures, or geometric forms created by bending paper clips with blue experiences to retrieve, some contextual (episodic) beads into unique shapes, (Rock, Schreilber, and Ro, 1994). information must first be accessed (Mayes & Roberts, A four-item force-choice recognition test for the novel 2001). While all of these measures seem to share this geometric forms was employed, with the task name serving contextual component, none adequately examines the as the retrieval cue. -

Examining the Effect of Interference on Short-Term Memory Recall of Arabic Abstract and Concrete Words Using Free, Cued, and Serial Recall Paradigms

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 6 No. 6; December 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Examining the Effect of Interference on Short-term Memory Recall of Arabic Abstract and Concrete Words Using Free, Cued, and Serial Recall Paradigms Ahmed Mohammed Saleh Alduais (Corresponding author) Department of Linguistics, Social Sciences Institute Ankara University, 06100 Sıhhiye, Ankara, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] Yasir Saad Almukhaizeem Department of Linguistics and Translation, College of Languages and Translation King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.7 Received: 29/05/2015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.7 Accepted: 18/08/2015 The research is financed by Research Centre in the College of Languages and Translation Studies and the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Abstract Purpose: To see if there is a correlation between interference and short-term memory recall and to examine interference as a factor affecting memory recalling of Arabic and abstract words through free, cued, and serial recall tasks. Method: Four groups of undergraduates in King Saud University, Saudi Arabia participated in this study. The first group consisted of 9 undergraduates who were trained to perform three types of recall for 20 Arabic abstract and concrete words. The second, third and fourth groups consisted of 27 undergraduates where each group was trained only to perform one recall type: free recall, cued recall and serial recall respectively. -

Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Evolution of Metacognition

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 29 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Handbook of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky, Robert A. Bjork Evolution of Metacognition Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 Janet Metcalfe Published online on: 28 May 2008 How to cite :- Janet Metcalfe. 28 May 2008, Evolution of Metacognition from: Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Routledge Accessed on: 29 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Evolution of Metacognition Janet Metcalfe Introduction The importance of metacognition, in the evolution of human consciousness, has been emphasized by thinkers going back hundreds of years. While it is clear that people have metacognition, even when it is strictly defined as it is here, whether any other animals share this capability is the topic of this chapter. -

Discovery Misattribution: When Solving Is Confused with Remembering

Journal of Experimental Psychology: General Copyright 2007 by the American Psychological Association 2007, Vol. 136, No. 4, 577–592 0096-3445/07/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.4.577 Discovery Misattribution: When Solving Is Confused With Remembering Sonya Dougal Jonathan W. Schooler New York University University of British Columbia This study explored the discovery misattribution hypothesis, which posits that the experience of solving an insight problem can be confused with recognition. In Experiment 1, solutions to successfully solved anagrams were more likely to be judged as old on a recognition test than were solutions to unsolved anagrams regardless of whether they had been studied. Experiment 2 demonstrated that anagram solving can increase the proportion of “old” judgments relative to words presented outright. Experiment 3 revealed that under certain conditions, solving anagrams influences the proportion of “old” judgments to unrelated items immediately following the solved item. In Experiment 4, the effect of solving was reduced by the introduction of a delay between solving the anagrams and the recognition judgments. Finally, Experiments 5 and 6 demonstrated that anagram solving leads to an illusion of recollection. Keywords: recognition, memory misattribution, recollection, insight problem There is something very similar about the experience of recol- found that increasing the perceptual fluency of items on a recog- lection and that of discovery. In both cases, a thought comes to nition test by preceding them with subliminally -

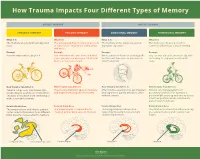

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory.