Europe As a Symbolic Resource Working Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej

CENTRUM BADANIA OPINII SPOŁECZNEJ SEKRETARIAT 629 - 35 - 69, 628 - 37 - 04 UL. ŻURAWIA 4A, SKR. PT.24 OŚRODEK INFORMACJI 693 - 46 - 92, 625 - 76 - 23 00 - 503 W A R S Z A W A TELEFAX 629 - 40 - 89 INTERNET http://www.cbos.pl E-mail: [email protected] BS/158/2005 WYBORY PREZYDENCKIE: PEWNOŚĆ GŁOSOWANIA, PREFERENCJE NIEZDECYDOWANYCH I PRZEWIDYWANIA CO DO WYNIKU WYBORÓW KOMUNIKAT Z BADAŃ WARSZAWA, WRZESIEŃ 2005 PRZEDRUK MATERIAŁÓW CBOS W CAŁOŚCI LUB W CZĘŚCI ORAZ WYKORZYSTANIE DANYCH EMPIRYCZNYCH JEST DOZWOLONE WYŁĄCZNIE Z PODANIEM ŹRÓDŁA Prezentowane wyniki pochodzą z wrześniowego sondażu1 przeprowadzonego przed wyborami parlamentarnymi. Podstawowe informacje dotyczące przewidywanego udziału w wyborach prezydenckich i preferencji wyborczych były już publikowane2. Obecnie powracamy do tych danych proponując szersze ujęcie tematu. PEWNOŚĆ DECYZJI WYBORCZYCH W tym roku Polacy nie mają łatwego zadania, jeśli chodzi o podejmowanie decyzji w wyborach prezydenckich. Lista ewentualnych pretendentów do prezydentury bardzo długo pozostawała niekompletna, później ze startu w wyborach zrezygnował tracący poparcie Zbigniew Religa. Przed koniecznością zmiany decyzji wyborczej postawieni zostali zwolennicy jednego z najbardziej liczących się kandydatów - Włodzimierza Cimoszewicza, który zrezygnował z ubiegania się o najwyższy urząd w państwie. Ostatnio mówi się też, że nad wycofaniem swojej kandydatury zastanawia się Maciej Giertych, choć oficjalnie wiadomość ta nie została jeszcze potwierdzona. Zmiany w ofercie wyborczej nie sprzyjają krystalizacji i stabilności preferencji wyborczych. Trudno też oprzeć się wrażeniu, że początkowo Polacy z dużą rezerwą podchodzili do oferty wyborczej, bazującej głównie na dość często kontrowersyjnych liderach partyjnych. Przez długi czas wyborcy nie traktowali swych wyborów politycznych jako ostatecznych i niezmiennych. Stabilizacji elektoratów zapewne nie sprzyjały także zmiany w sondażowych rankingach poparcia dla kandydatów. -

Być Premierem

Być premierem Materiał składa się z sekcji: "Premierzy III RP", "Tadeusz Mazowiecki", "Premierzy II Rzeczpospolitej". Materiał zawiera: - 19 ilustracji (fotografii, obrazów, rysunków), 3 ćwiczenia; - wirtualny spacer po kancelarii Prezesa Rady Ministrów wraz z opisem jej historii; - opis informacji i opinii o Tadeuszu Mazowieckim wraz ćwiczeniem do wykonania na ich podstawie; - zdjęcie, na którym przedstawiono premiera Tadeusza Mazowieckiego w 1989 r.; - galerię zdjęć premierów III RP (Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Jan Krzysztof Bielecki, Jan Olszewski, Waldemar Pawlak, Hanna Suchocka, Józef Oleksy, Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz, Jerzy Buzek, Leszek Miller, Marek Belka, Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz, Jarosław Kaczyński, Donald Tusk, Ewa Kopacz, Beata Szydło); - opis działalności politycznej premierów II RP (Wincenty Witos, Walery Sławek, Felicjan Sławoj Składkowski); - zdjęcie, na którym przedstawiono Wincentego Witosa przemawiającego do tłumu; - zdjęcie, na którym przedstawiono Walerego Sławka; - zdjęcie, na którym przedstawiono Felicjana Sławoj Składkowskiego przemawiającego do urzędników Prezydium Rady Ministrów; - ćwiczenie, które polega na poszukaniu i przedstawieniu różnych ciekawostek o życiu znanych polityków z okresu II i III Rzeczypospolitej; - propozycje pytań do dyskusji na tematy polityczne; - ćwiczenie, które polega na opracowaniu galerii premierów II RP. Być premierem Kancelaria Prezesa Rady Ministrów Laleczki, licencja: CC BY-SA 4.0 Zobacz, jak wygląda kancelaria Prezesa Rady Ministrów, miejsce pracy premiera. Źródło: PANORAMIX, licencja: CC BY 3.0. Premierzy III RP Sprawowanie urzędu premiera to wielki zaszczyt, ale i ogromna odpowiedzialność. Prezes Rady Ministrów jest zgodnie z Konstytucją RP dopiero czwartą osobą w państwie (po prezydencie, marszałakch Sejmu i Senatu), ale w praktyce skupia w swoich rękach niemal całą władzę wykonawczą. Od decyzji, które podejmuje szef rządu, zależy jakość życia wielu milionów ludzi. Znane są dzieje narodów, które pod mądrym przewodnictwem rozkwitały, a pod złym popadały w biedę i chaos. -

Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej

CENTRUM BADANIA OPINII SPOŁECZNEJ SEKRETARIAT 629 - 35 - 69, 628 - 37 - 04 UL. ŻURAWIA 4A, SKR. PT.24 OŚRODEK INFORMACJI 693 - 46 - 92, 625 - 76 - 23 00 - 503 W A R S Z A W A TELEFAX 629 - 40 - 89 INTERNET http://www.cbos.pl E-mail: [email protected] BS/48/2009 ZAUFANIE DO POLITYKÓW W MARCU KOMUNIKAT Z BADAŃ WARSZAWA, MARZEC 2009 PRZEDRUK I ROZPOWSZECHNIANIE MATERIAŁÓW CBOS W CAŁOŚCI LUB W CZĘŚCI ORAZ WYKORZYSTANIE DANYCH EMPIRYCZNYCH JEST DOZWOLONE WYŁĄCZNIE Z PODANIEM ŹRÓDŁA W marcu1 politykiem cieszącym się wśród Polaków największym zaufaniem jest minister spraw zagranicznych Radosław Sikorski (61%), który minimalnie wyprzedza w tym rankingu premiera Donalda Tuska (59%) oraz Lecha Wałęsę (58%). Zaufaniem nieco ponad połowy Polaków cieszy się marszałek Sejmu Bronisław Komorowski (52%), niewiele mniej osób ufa wicepremierowi i ministrowi gospodarki Waldemarowi Pawlakowi (50%). Na zbliżonym poziomie kształtuje się też zaufanie do Włodzimierza Cimoszewicza (48%), którego nazwisko ponownie umieściliśmy na naszej liście w związku ze zgłoszeniem jego kandydatury na stanowisko sekretarza generalnego Rady Europy. Kolejne miejsca w rankingu zaufania do polityków, jednak już z wyraźnie słabszym wynikiem, zajmują liderzy ugrupowań lewicowych Marek Borowski (40%) oraz Wojciech Olejniczak (37%). Poza czołówką najpopularniejszych polityków znalazł się w tym miesiącu Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz, do którego zaufanie deklaruje obecnie co trzeci ankietowany (33%). Niemal tyle samo sympatyków mają prezydent Lech Kaczyński (32% deklaracji zaufania), minister zdrowia Ewa Kopacz (32%) oraz szef MON Bogdan Klich (31%). Zaufaniem niespełna jednej trzeciej badanych cieszą się: przewodniczący klubu parlamentarnego PO Zbigniew Chlebowski (29%), Janusz Palikot (29%), a także wicepremier i szef MSWiA Grzegorz Schetyna (28%). Co czwarty respondent deklaruje zaufanie do marszałka Senatu Bogdana Borusewicza (26%) oraz do lidera głównej partii opozycyjnej Jarosława Kaczyńskiego (25%). -

Konrad Raczkowski Public Management Theory and Practice 4

Konrad Raczkowski Public Management Theory and Practice 4^1 Springer O.ST f" 'S 1 State as a Special Organisation of Society 1 1.1 Notion and Origins of the State 1 1.2 State According to Social Teachings of the Church 4 1.3 Tasks for State as the System of Institutions 6 1.4 Governance Versus Public Management 9 References 16 2 Flanning and Decision Making in Public Management 21 2.1 The Essence of Flanning 21 2.2 Decisions and Their Classification 27 2.3 Decision Making in Conditions of Certainty, Risk and Uncertainty 33 2.4 Heterogeneous Knowledge in Strategie Flanning and Decision Making 36 2.5 Flanning and Decision Making in Political Transformation 38 2.6 Institutional Development Flanning on Local Government Level (IDF Method) 45 References 49 3 State Organisation for Institutional and Systemic Perspective 55 3.1 Dynamic Equilibrium of Organised Things 55 3.2 New Institutional Economy and State Organisation 58 3.3 Virtual Social Structure in Actual State Organisation 62 3.4 Organisational Social System of the State 64 3.5 Role of Non-governmental Organisations in the State 68 3.6 Main Models of State Organisation 73 3.7 Models of Organisation of Unitary States 80 3.8 Organisation of Multilevel Management in European Union 87 References 93 4 Managing and Leading in Public Organisations 99 4.1 Managing the Intellectual Capital in Public Organisation 99 4.2 Leadership in Network-Dominated Public Sphere 104 xiii xiv Contents 4.3 Global Crisis of Public Leadership 111 4.4 Information and Disinformation: Key Tools of State Management -

Republic of Poland

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights REPUBLIC OF POLAND PRE-TERM PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 21 October 2007 OSCE/ODIHR Election Assessment Mission Final Report Warsaw 20 March 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................................... 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.............................................................. 2 III. BACKGROUND.......................................................................................................................... 2 IV. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................................ 3 A. OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................3 B. ELECTORAL SYSTEM ................................................................................................................4 C. SUFFRAGE AND CANDIDACY ELIGIBILITY ...............................................................................5 D. COMPLAINTS AND APPEALS......................................................................................................6 E. OBSERVERS ...............................................................................................................................7 V. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION............................................................................................. 7 A. OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................7 -

Chairperson's Statement United Nations Conference on Anti-Corruption Measures, Good Governance & Human Rights

Chairperson’s Statement United Nations Conference on Anti-Corruption Measures, Good Governance & Human Rights Warsaw, Republic of Poland, 8-9 November 2006 Introduction The United Nations Conference on Anti-Corruption Measures, Good Governance and Human Rights was convened in Warsaw, Republic of Poland, from 8-9 November 2006. It was organized by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in cooperation with the Government of the Republic of Poland. The Conference had a practical orientation and was structured in a manner that could lead to the discussion of practical and concrete recommendations. There were more than 240 participants from more than 100 countries, including anti-corruption and human rights experts, governments’ representatives, public officials, civil society and private sector actors involved in leading national anti- corruption efforts. The Chairman of the Conference was H.E. Anna Fotyga, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland. The Conference was organized in response to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights Resolution 2005/68, which requested the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights “[...] to convene a seminar in 2006 [...] on the role of anti- corruption measures at the national and international levels in good governance practices for the promotion and protection of human rights.” The Conference was a follow-up to the joint OHCHR-UNDP Seminar on good governance practices for the promotion and protection of human rights, which took place in Seoul in September 2004. The conclusions of that Seminar emphasized the mutually reinforcing, and sometimes overlapping, relationship between good governance and human rights. -

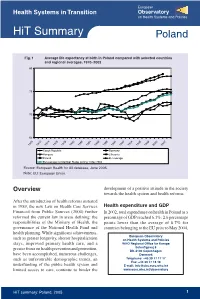

Poland 2005 Hit Summary

European Health Systems in Transition Observatory on Health Systems and Policies HiT Summary Poland Fig. Average life expectancy at birth in Poland compared with selected countries and regional averages, 970–2003 80 75 70 65 1970 1972 1974 1976 1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 Czech Republic Germany Hungary Lithuania Poland EU average EU average for Member States joining 1 May 2004 Source: European Health for All database, June 2005. Note: EU: European Union. Overview development of a positive attitude in the society towards the health system and health reforms. After the introduction of health reforms initiated in 1989, the new Law on Health Care Services Health expenditure and GDP Financed from Public Sources (2004) further In 2002, total expenditure on health in Poland as a reformed the current law in areas defining: the percentage of GDP reached 6.1%: 2.6 percentage responsibilities of the Ministry of Health, the points lower than the average of 8.7% for governance of the National Health Fund and countries belonging to the EU prior to May 2004, health planning. While significant achievements, European Observatory such as greater longevity, shorter hospitalization on Health Systems and Policies stays, improved primary health care, and a WHO Regional Office for Europe greater focus on health prevention and promotion, Scherfigsvej 8 DK-200 Copenhagen have been accomplished, numerous challenges, Denmark such as unfavourable demographic trends, an Telephone: +45 39 7 7 7 Fax: +45 39 7 8 8 underfunding of the public health system and E-mail: [email protected] limited access to care, continue to hinder the www.euro.who.int/observatory HiT summary: Poland, 2005 and 0.5 percentage points below the average of in negative natural population growth as in new EU Member States. -

15 Czerwca 2007 R.) Str

str. str. TREŚĆ 43. posiedzenia Sejmu (Obrady w dniu 15 czerwca 2007 r.) str. str. Wznowienie posiedzenia Poseł Izabela Kloc . 375 Zmiana porządku dziennego Poseł Joanna Fabisiak . 375 Marszałek. 349 Poseł Grażyna Jolanta Ciemniak . 375 Punkt 40. porządku dziennego: Infor- Poseł Krzysztof Michałkiewicz . 376 macja Rządu na temat stanowiska Poseł Stanisław Pięta . 376 negocjacyjnego Polski w związku ze Poseł Mirosław Orzechowski . 376 szczytem Unii Europejskiej w dniach Poseł Stanisław Kalemba . 377 21–22 czerwca 2007 r. Poseł Jarosław Kalinowski . 377 Punkt 41. porządku dziennego: Sprawoz- Poseł Krzysztof Lipiec . 378 danie Komisji Spraw Zagranicznych Poseł Jarosław Kalinowski . 378 o poselskich projektach uchwał: Poseł Stanisław Papież . 378 1) w sprawie udzielenia poparcia dla sta- Poseł Lech Kuropatwiński . 379 nowiska Rządu Polskiego dotyczącego Poseł Jarosław Kalinowski . 379 Traktatu ustanawiającego Konstytucję Poseł Tadeusz Iwiński . 379 dla Europy, Poseł Tomasz Latos . 380 2) w sprawie negocjacji nowego trakta- (Przerwa w posiedzeniu) tu UE Minister Spraw Zagranicznych Anna Fotyga . 350 Wznowienie posiedzenia Poseł Krzysztof Lisek . 353 Punkty 40. i 41. porządku dziennego (cd.) Poseł Paweł Zalewski. 354 Podsekretarz Stanu w Ministerstwie Spraw Poseł Bronisław Komorowski . 355 Zagranicznych Krzysztof Szczerski . 380 Poseł Wojciech Olejniczak . 357 Poseł Tadeusz Iwiński . 382 Minister Spraw Zagranicznych Anna Fotyga . 359 Podsekretarz Stanu w Ministerstwie Spraw Poseł Andrzej Lepper. 359 ZagranicznychKrzysztof Szczerski . 383 Poseł Roman Giertych. 361 Poseł Krzysztof Lisek . 383 Poseł Bronisław Komorowski . 363 (Przerwa w posiedzeniu) Poseł Roman Giertych . 363 Poseł Waldemar Pawlak . 364 Wznowienie posiedzenia Wiceprezes Rady Ministrów Zmiana porządku dziennego Minister Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi Marszałek. 384 Andrzej Lepper . 366 Punkt 34. porządku dziennego: Sprawoz- Poseł Waldemar Pawlak . 366 danie Komisji Infrastruktury Poseł Marek Jurek. -

LPR Government Coalition, May 2006, and the Expectations from the Pis - Self-Defence - LPR Coalition, June 2006

CBOS MAY 2006 ISSN 1233 - 7250 THE POLES ABOUT THE PIS - SELF-DEFENCE - LPR IN THIS ISSUE: GOVERNMENT COALITION R THE POLES ABOUT After six months of a minority THE PIS - SELF-DEFENCE cabinet formed by the Law and Justice WHAT IS YOUR OPINION ABOUT THE PIS - SELF- DEFENCE - LPR COALITION? - LPR GOVERNMENT (PiS), a majority coalition with the Self- COALITION It is too early to evaluate this Defence and the League of Polish Families coalition, let us wait for the (LPR) was formed. The Self-Defence and effects of its work the LPR are often seen as populist and R THE ATTITUDE nationalist parties. The reactions of the TO THE GOVERNMENT 47% public opinion, although less extreme than This coalition can do AFTER ITS 6% a lot of good RECONSTRUCTION those prevailing in Polish and foreign media, are not favourable. The new 13% coalition has been received by the Poles 34% Difficult to say R THE IMPORTANCE without much hope. Only 12% of the OF RELIGION respondents were glad that it was formed, One cannot expect anything good from whereas more than three times as many the PiS - Self-Defence -LPR coalition (36%) were worried. However, the most R PSYCHOLOGICAL common reaction to forming the new STRESS IN GEORGIA, The PiS - Self-Defence - LPR coalition government coalition was indifference (43%). THE UKRAINE, government will manage to carry out reforms HUNGARY AND POLAND and speed up the country's development The prevailing opinion is that people should wait with the evaluation of the new coalition 21% until they see some effects of its work. -

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3

COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES Original CSES file name: cses2_codebook_part3_appendices.txt (Version: Full Release - December 15, 2015) GESIS Data Archive for the Social Sciences Publication (pdf-version, December 2015) ============================================================================================= COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS (CSES) - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS APPENDIX II: PRIMARY ELECTORAL DISTRICTS FULL RELEASE - DECEMBER 15, 2015 VERSION CSES Secretariat www.cses.org =========================================================================== HOW TO CITE THE STUDY: The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 3 FULL RELEASE [dataset]. December 15, 2015 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module3.2015-12-15 These materials are based on work supported by the American National Science Foundation (www.nsf.gov) under grant numbers SES-0451598 , SES-0817701, and SES-1154687, the GESIS - Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, the University of Michigan, in-kind support of participating election studies, the many organizations that sponsor planning meetings and conferences, and the many organizations that fund election studies by CSES collaborators. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding organizations. =========================================================================== IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING FULL RELEASES: This dataset and all accompanying documentation is the "Full Release" of CSES Module 3 (2006-2011). Users of the Final Release may wish to monitor the errata for CSES Module 3 on the CSES website, to check for known errors which may impact their analyses. To view errata for CSES Module 3, go to the Data Center on the CSES website, navigate to the CSES Module 3 download page, and click on the Errata link in the gray box to the right of the page. -

Populism in Poland

PopulismPopulism inin PolandPoland byby OlgaOlga WysockaWysocka Politische Kommunikation in der globalisierten Welt: Aufmerksamkeit für politische Konzepte, Personen und Staaten 5/6 October 2006, Mainz PopulismPopulism „An ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, „the pure people“ versus „the corrupt elite“, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the generall will of the people“ Cas Mudde 2004 Charismatic leadership Direct communication PopulismPopulism inin PolandPoland BeforeBefore 20012001 Solidarność (Movement) Lech Wałęsa, Stan Tymiński (Populist leaders) Self-Defence, Alternative (From movement to party) AfterAfter 20012001 Self-Defence (Sociopopulism) League of Polish Families (Populist radical right-wing) 20052005 andand laterlater Law and Justice Self-Defence League of Polish Families „The most profitable areas of Polish economy are dominated by a "network", a network connected with the people from the former and current secret service. This is specific feature of the Polish reality in the last 17 years (...) All governments of III RP, except from the cabinet of Jan Olszewski, were connected in some ways with that network, (…). Today, it is not so easy to lie. We need to look for other methods. Thus, we want to break this “curtain” off. And this does not only mean discrediting the network and its defenders, it also means transforming Poland into the country of Polish citizens. (…) We will not allow defenders of criminals to succeed. There will be no dictatorship in Poland, there will be not authoritarian governments, only stupid people can believe otherwise. There will be law and order. There will be law and order in Poland because this is in the interest of ordinary Polish citizens. -

POLISH INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING, 1976-1989 a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Scho

MIGHTIER THAN THE SWORD: POLISH INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING, 1976-1989 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. By Siobhan K. Doucette, M.A. Washington, DC April 11, 2013 Copyright 2013 by Siobhan K. Doucette All Rights Reserved ii MIGHTIER THAN THE SWORD: POLISH INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING, 1976-1989 Siobhan K. Doucette, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Andrzej S. Kamiński, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes the rapid growth of Polish independent publishing between 1976 and 1989, examining the ways in which publications were produced as well as their content. Widespread, long-lasting independent publishing efforts were first produced by individuals connected to the democratic opposition; particularly those associated with KOR and ROPCiO. Independent publishing expanded dramatically during the Solidarity-era when most publications were linked to Solidarity, Rural Solidarity or NZS. By the mid-1980s, independent publishing obtained new levels of pluralism and diversity as publications were produced through a bevy of independent social milieus across every segment of society. Between 1976 and 1989, thousands of independent titles were produced in Poland. Rather than employing samizdat printing techniques, independent publishers relied on printing machines which allowed for independent publication print-runs in the thousands and even tens of thousands, placing Polish independent publishing on an incomparably greater scale than in any other country in the Communist bloc. By breaking through social atomization and linking up individuals and milieus across class, geographic and political divides, independent publications became the backbone of the opposition; distribution networks provided the organizational structure for the Polish underground.