Contemporary Poetry in Scots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Borderlines: Contemporary Scottish Gothic

Notes Introduction: Borderlines: Contemporary Scottish Gothic 1. Caroline McCracken-Flesher, writing shortly before the latter film’s release, argues that it is, like the former, ‘still an outsider tale’; despite the emphasis on ‘Scottishness’ within these films, they could only emerge from outside Scotland. Caroline McCracken-Flesher (2012) The Doctor Dissected: A Cultural Autopsy of the Burke and Hare Murders (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 20. 2. Kirsty A. MacDonald (2009) ‘Scottish Gothic: Towards a Definition’, The Bottle Imp, 6, 1–2, p. 1. 3. Andrew Payne and Mark Lewis (1989) ‘The Ghost Dance: An Interview with Jacques Derrida’, Public, 2, 60–73, p. 61. 4. Nicholas Royle (2003) The Uncanny (Manchester: Manchester University Press), p. 12. 5. Allan Massie (1992) The Hanging Tree (London: Mandarin), p. 61. 6. See Luke Gibbons (2004) Gaelic Gothic: Race, Colonization, and Irish Culture (Galway: Arlen House), p. 20. As Coral Ann Howells argues in a discussion of Radcliffe, Mrs Kelly, Horsley-Curteis, Francis Lathom, and Jane Porter, Scott’s novels ‘were enthusiastically received by a reading public who had become accustomed by a long literary tradition to associate Scotland with mystery and adventure’. Coral Ann Howells (1978) Love, Mystery, and Misery: Feeling in Gothic Fiction (London: Athlone Press), p. 19. 7. Ann Radcliffe (1995) The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne, ed. Alison Milbank (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 3. 8. As James Watt notes, however, Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne remains a ‘derivative and virtually unnoticed experiment’, heavily indebted to Clara Reeves’s The Old English Baron. James Watt (1999) Contesting the Gothic: Fiction, Genre and Cultural Conflict, 1764–1832 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. -

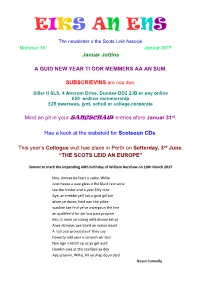

EIKS an ENS Nummer 10

EIKS AN ENS The newsletter o the Scots Leid Associe Nummer 10 Januar 2017 Januar Jottins A GUID NEW YEAR TI OOR MEMMERS AA AN SUM. SUBSCRIEVINS are nou due. Siller ti SLS, 4 Ancrum Drive, Dundee DD2 2JB or pey online £20 ordinar memmership £25 owerseas, jynt, schuil or college,corporate Mind an pit in your entries afore Januar 31st. Hae a keek at the wabsteid for Scotsoun CDs. This year’s Collogue wull hae place in Perth on Setterday, 3rd June. “THE SCOTS LEID AN EUROPE” Sonnet to mark the impending 60th birthday of William Hershaw on 19th March 2017 Nou, dinnae be feart o saxty, Willie Juist heeze a wee gless o the bluid reid wine tae the hinder end o year fifty nine Aye, an mebbe ye'll tak a guid gill tae afore ye dover, heid oan the pillae wauken tae find ye’ve owergaun the line an qualifee’d for yer bus pass propine Ken, it maks ye strang whit disnae kill ye Ance domine, aye baird an makar bauld A ‘cultural provocateur’ they say Fowerty odd year o scrievin wir leid Nae sign o lettin up as ye get auld Howkin awa at the coalface aa dey Aye screivin, Willie, till ye drap doun deid Kevin Connelly Burns’ Hamecomin When taverns stert tae stowe wi folk, Bit tae oor tale. Rab’s here as guest, An warkers thraw aff labour’s yoke, Tae handsel this by-ornar fest – As simmer days are waxin lang, Twa hunnert years an fifty’s passed An couthie chiels brak intae sang; Syne he blew in on Janwar’s blast. -

Tom Leonard (1944 -2018) — 'Notes Personal' in Response to His Life

Tom Leonard (1944 -2018) — ‘Notes Personal’ in Response to his Life and Work an essay by Jim Ferguson 1. How I met the human being named ‘Tom Leonard’ I was ill with epilepsy and post-traumatic stress disorder. It was early in 1986. I was living in a flat on Causeyside Street, Paisley, with my then partner. We were both in our mid-twenties and our relationship was happy and loving. We were rather bookish with quite a strong sense of Scottish and Irish working class identity and an interest in socialism, social justice. I think we both held the certainty that the world could be changed for the better in myriad ways, I know I did and I think my partner did too. You feel as if you share these basic things, a similar basic outlook, and this is probably why you want to live in a little tenement flat with one human being rather than any other. We were not career minded and our interest in money only stretched so far as having enough to live on and make ends meet. Due to my ill health I wasn’t getting out much and rarely ventured far from the flat, though I was working on ‘getting better’. In these circumstances I found myself filling my afternoons writing stories and poems. I had a little manual portable typewriter and would sit at a table and type away. I was a very poor typist which made poetry much more appealing and enjoyable because it could be done in fewer words with a lot less tipp-ex. -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

Phd Commentary

Barron, Richard (2021) From text to music: a Scots portfolio. PhD thesis. (commentary) http://theses.gla.ac.uk/82393/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Commentary on PhD Composition Portfolio From text to music: a Scots portfolio Richard Barron School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow Revised June 2021 1 Abstract This portfolio presents seven pieces or sequences of music setting or drawn from texts in Scots; in three of them, parts of the text also use other languages. The pieces are of varying scale, forces and forms. The commentary outlines the range and nature of the texts used and the compositional approaches taken to their use. The musical idioms of the pieces are discussed, as well as their forms and the forces used. The pieces are largely post-tonal and several are influenced by the serialist tradition. The commentary considers the portfolio in the broad context of Scots literature and culture, and notes the international context of three of the pieces. -

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175Th Anniversary Honorees the Makar’S Medal

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175th Anniversary Honorees The Makar’s Medal The Chicago Scots have created a new award, the Makar’s Medal, to commemorate their 175th anniversary as the oldest nonprofit in Illinois. The Makar’s Medal will be awarded every five years to the seated Scots Makar – the poet laureate of Scotland. The inaugural recipient of the Makar’s Medal is Jackie Kay, a critically acclaimed poet, playwright and novelist. Jackie was appointed the third Scots Makar in March 2016. She is considered a poet of the people and the literary figure reframing Scottishness today. Photo by Mary McCartney Jackie was born in Edinburgh in 1961 to a Scottish mother and Nigerian father. She was adopted as a baby by a white Scottish couple, Helen and John Kay who also adopted her brother two years earlier and grew up in a suburb of Glasgow. Her memoir, Red Dust Road published in 2010 was awarded the prestigious Scottish Book of the Year, the London Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Jr. Ackerley prize. It was also one of 20 books to be selected for World Book Night in 2013. Her first collection of poetry The Adoption Papers won the Forward prize, a Saltire prize and a Scottish Arts Council prize. Another early poetry collection Fiere was shortlisted for the Costa award and her novel Trumpet won the Guardian Fiction Award and was shortlisted for the Impac award. Jackie was awarded a CBE in 2019, and made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2002. -

Contemporary Gaelic Language and Culture: an Introduction (SCQF Level 5)

National Unit specification: general information Unit title: Contemporary Gaelic Language and Culture: An Introduction (SCQF level 5) Unit code: FN44 11 Superclass: FK Publication date: July 2011 Source: Scottish Qualifications Authority Version: 01 Summary The purpose of this Unit is to provide candidates with the knowledge and skills to enable them to understand development issues relating to the Gaelic language; understand contemporary Gaelic media, performing arts and literature; and provide the opportunity to enhance the four language skills of speaking, listening, reading and writing. This is a mandatory Unit within the National Progression Award in Contemporary Gaelic Songwriting and Production but can also be taken as a free-standing Unit. This Unit is suitable both for candidates who are fluent Gaelic speakers or Gaelic learners who have beginner level skills in written and spoken Gaelic. It can be delivered to a wide range of learners who have an academic, vocational or personal interest in the application of Gaelic in the arts and media. It is envisaged that candidates successfully completing this Unit will be able to progress to further study in Gaelic arts. Outcomes 1 Describe key factors contributing to Gaelic language and cultural development. 2 Describe key elements of the contemporary Gaelic arts and media world. 3 Apply Gaelic language skills in a range of contemporary arts and media contexts. Recommended entry While entry is at the discretion of the centre, candidates are expected to have, as a minimum, basic language skills in Gaelic. This may be evidenced by the attainment of Intermediate 1 Gaelic (Learners) or equivalent ability in the four skills of listening, speaking, reading and writing. -

ROBERT BURNS and FRIENDS Essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows Presented to G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Robert Burns and Friends Robert Burns Collections 1-1-2012 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Kenneth Simpson See next page for additional authors Publication Info 2012, pages 1-192. © The onC tributors, 2012 All rights reserved Printed and distributed by CreateSpace https://www.createspace.com/900002089 Editorial contact address: Patrick Scott, c/o Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries, 1322 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4392-7097-4 Scott, P., Simpson, K., eds. (2012). Robert Burns & Friends essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy. P. Scott & K. Simpson (Eds.). Columbia, SC: Scottish Literature Series, 2012. This Book - Full Text is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Burns and Friends by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author(s) Patrick G. Scott, Kenneth Simpson, Carol Mcguirk, Corey E. Andrews, R. D. S. Jack, Gerard Carruthers, Kirsteen McCue, Fred Freeman, Valentina Bold, David Robb, Douglas S. Mack, Edward J. Cowan, Marco Fazzini, Thomas Keith, and Justin Mellette This book - full text is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/burns_friends/1 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy G. Ross Roy as Doctor of Letters, honoris causa June 17, 2009 “The rank is but the guinea’s stamp, The Man’s the gowd for a’ that._” ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. -

"Dae Scotsmen Dream O 'Lectric Leids?" Robert Crawford's Cyborg Scotland

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 "Dae Scotsmen Dream o 'lectric Leids?" Robert Crawford's Cyborg Scotland Alexander Burke Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3272 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i © Alexander P. Burke 2013 All Rights Reserved i “Dae Scotsmen Dream o ‘lectric Leids?” Robert Crawford’s Cyborg Scotland A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English at Virginia Commonwealth University By Alexander Powell Burke Bachelor of Arts in English, Virginia Commonwealth University May 2011 Director: Dr. David Latané Associate Chair, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December, 2013 ii Acknowledgment I am forever indebted to the VCU English Department for providing me with a challenging and engaging education, and its faculty for making that experience enjoyable. It is difficult to single out only several among my professors, but I would like to acknowledge David Wojahn and Dr. Marcel Cornis-Pope for not only sitting on my thesis committee and giving me wonderful advice that I probably could have followed more closely, but for their role years prior of inspiring me to further pursue poetry and theory, respectively. -

Hugh Macdiarmid and Sorley Maclean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters

Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters by Susan Ruth Wilson B.A., University of Toronto, 1986 M.A., University of Victoria, 1994 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Susan Ruth Wilson, 2007 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Dr. Iain Higgins_(English)__________________________________________ _ Supervisor Dr. Tom Cleary_(English)____________________________________________ Departmental Member Dr. Eric Miller__(English)__________________________________________ __ Departmental Member Dr. Paul Wood_ (History)________________________________________ ____ Outside Member Dr. Ann Dooley_ (Celtic Studies) __________________________________ External Examiner ABSTRACT This dissertation, Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters, transcribes and annotates 76 letters (65 hitherto unpublished), between MacDiarmid and MacLean. Four additional letters written by MacDiarmid’s second wife, Valda Grieve, to Sorley MacLean have also been included as they shed further light on the relationship which evolved between the two poets over the course of almost fifty years of friendship. These letters from Valda were archived with the unpublished correspondence from MacDiarmid which the Gaelic poet preserved. The critical introduction to the letters examines the significance of these poets’ literary collaboration in relation to the Scottish Renaissance and the Gaelic Literary Revival in Scotland, both movements following Ezra Pound’s Modernist maxim, “Make it new.” The first chapter, “Forging a Friendship”, situates the development of the men’s relationship in iii terms of each writer’s literary career, MacDiarmid already having achieved fame through his early lyrics and with the 1926 publication of A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle when they first met. -

Location and Destination in Alasdair Mac Mhaigshstir Alasdair's 'The

Riach, A. (2019) Location and destination in Alasdair mac Mhaigshstir Alasdair’s ‘The Birlinn of Clanranald’. In: Szuba, M. and Wolfreys, J. (eds.) The Poetics of Space and Place in Scottish Literature. Series: Geocriticism and spatial literary studies. Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, pp. 17-30. ISBN 9783030126445. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/188312/ Deposited on: 13 June 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Location and Destination in Alasdair mac Mhaigshstir Alasdair’s ‘The Birlinn of Clanranald’ Alan Riach FROM THE POETICS OF SPACE AND PLACE IN SCOTTISH LITERATURE, MONIKA SZUBA AND JULIEN WOLFREYS, EDS., (CHAM, SWITZERLAND: PALGRAVE MACMILLAN, 2019), PP.17-30 ‘THE BIRLINN OF CLANRANALD’ is a poem which describes a working ship, a birlinn or galley, its component parts, mast, sail, tiller, rudder, oars and the cabes (or oar-clasps, wooden pommels secured to the gunwale) they rest in, the ropes that connect sail to cleats or belaying pins, and so on, and the sixteen crewmen, each with their appointed role and place; and it describes their mutual working together, rowing, and then sailing out to sea, from the Hebrides in the west of Scotland, from South Uist to the Sound of Islay, then over to Carrickfergus in Ireland. The last third of the poem is an astonishing, terrifying, exhilarating description of the men and the ship in a terrible storm that blows up, threatening to destroy them, and which they pass through, only just making it to safe harbour, mooring and shelter.