Yugoslav Foreign Policy International Balancing on a High Wire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Ho Chi Minh's Thought on Preventing War, Settling Disputes

The Journal of Middle East and North Africa Sciences 2021; 7(06) http://www.jomenas.org Ho Chi Minh's Thought on Preventing War, Settling Disputes, Contradictions BY Peaceful Measures Ph.D. Le Nhi Hoa Regional Academy of Politics III, 232 Nguyen Cong Tru, Son Tra District, Da Nang city, Việt Nam [email protected] Abstract. Respect for independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity; not to use force or threaten to use force in international relations; equal and mutually beneficial cooperation; the peaceful settlement of disputes and disputes are core principles and values of international law, the Charter of the United Nations; achievements and efforts of all nations in the world, including Vietnam. With the historical approach, the article in-depth clarifies a number of prominent points in Ho Chi Minh's thought about war prevention, settlement of disputes, disputes by peaceful means and their application in fight to protect the sovereignty and legitimate interests of Vietnam in the East Sea. To cite this article [Hoa, L. N. (2021). Ho Chi Minh's Thought on Preventing War, Settling Disputes, Contradictions BY Peaceful Measures. The Journal of Middle East and North Africa Sciences, 7(06), 20-25]. (P-ISSN 2412- 9763) - (e-ISSN 2412-8937). www.jomenas.org. 4 Keywords: Prevent War; Peaceful Measure; Ho Chi Minh.. 1. An assessment of Ho Chi Minh's outstanding countries and the determination of the Vietnamese people contributions: in protecting the national sovereignty and territorial An assessment of Ho Chi Minh's outstanding integrity of the country. “Vietnam has the right to enjoy contributions, the United Nations Educational, Scientific freedom and independence, and in fact has become a free and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) issued Resolution and independent country. -

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy Sophie Diamant Richardson Old Chatham, New York Bachelor of Arts, Oberlin College, 1992 Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics University of Virginia May, 2005 !, 11 !K::;=::: .' P I / j ;/"'" G 2 © Copyright by Sophie Diamant Richardson All Rights Reserved May 2005 3 ABSTRACT Most international relations scholarship concentrates exclusively on cooperation or aggression and dismisses non-conforming behavior as anomalous. Consequently, Chinese foreign policy towards small states is deemed either irrelevant or deviant. Yet an inquiry into the full range of choices available to policymakers shows that a particular set of beliefs – the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence – determined options, thus demonstrating the validity of an alternative rationality that standard approaches cannot apprehend. In theoretical terms, a belief-based explanation suggests that international relations and individual states’ foreign policies are not necessarily determined by a uniformly offensive or defensive posture, and that states can pursue more peaceful security strategies than an “anarchic” system has previously allowed. “Security” is not the one-dimensional, militarized state of being most international relations theory implies. Rather, it is a highly subjective, experience-based construct, such that those with different experiences will pursue different means of trying to create their own security. By examining one detailed longitudinal case, which draws on extensive archival research in China, and three shorter cases, it is shown that Chinese foreign policy makers rarely pursued options outside the Five Principles. -

Afghanistan and the Peace Through Development Paradigm: a Critical Assessment

E-journal promoted by the Campus for Peace, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya http://journal-of-conflictology.uoc.edu CONFLICTOLOGY IN PRACTICE Afghanistan and the Peace Through Development Paradigm: A Critical Assessment Katharina Merkel Submitted: December 2010 Accepted: March 2011 Published: May 2011 Abstract A plethora of academic literature indicates that, in the post Cold War political landscape, poverty and development deficits are key in sparking civil conflict. Out of this recognition a new paradigm has emerged which underpins the idea that, by working to overcome these deficits, the risk of conflict can be essentially reduced and/or mitigated. The ‘peace through development’ paradigm supports the assumptio n that development and security are essentially intertwined. In this paper I discuss the challenges and opportunities associated with the paradigm within the Afghan context, addressing the two core questions: (1) how are poverty and development deficits connected to violence and conflict? and (2) what are the prerequisites for development to play a conducive role in the peacebuilding alchemy? This paper argues that at large, sustainable peace in Afghanistan can only be achieved through sustainable development. However, it also recognises the tremendous challenges faced to fully capitalise on the peace dividend that development might be able to provide, and at the same time develops a roadmap for more conflict-sensitive development programming. Keywords peacebuilding, development, conflict resolution, poverty, Afghanistan, horizontal -

Yugoslav Ideology and Its Importance to the Soviet Bloc: an Analysis

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-1967 Yugoslav Ideology and Its Importance to the Soviet Bloc: An Analysis Christine Deichsel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Deichsel, Christine, "Yugoslav Ideology and Its Importance to the Soviet Bloc: An Analysis" (1967). Master's Theses. 3240. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3240 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YUGOSLAV IDEOLOGY AND ITS IMPORTANCE TO THE SOVIET BLOC: AN ANALYSIS by Christine Deichsel A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo., Michigan April 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In writing this thesis I have benefited from the advice and encouragement of Professors George Klein and William A. Ritchie. My thanks go to them and the other members of my Committee, namely Professors Richard J. Richardson and Alan Isaak. Furthermore, I wish to ex press my appreciation to all the others at Western Michi gan University who have given me much needed help and encouragement. The award of an assistantship and the intellectual guidance and stimulation from the faculty of the Department of Political Science have made my graduate work both a valuable experience and a pleasure. -

Tito's Yugoslavia

The Search for a Communist Legitimacy: Tito's Yugoslavia Author: Robert Edward Niebuhr Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1953 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History THE SEARCH FOR A COMMUNIST LEGITIMACY: TITO’S YUGOSLAVIA a dissertation by ROBERT EDWARD NIEBUHR submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE ABSTRACT . iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . iv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS . v NOTE ON TRANSLATIONS AND TERMS . vi INTRODUCTION . 1 1 A STRUGGLE FOR THE HEARTS AND MINDS: IDEOLOGY AND YUGOSLAVIA’S THIRD WAY TO PARADISE . 26 2 NONALIGNMENT: YUGOSLAVIA’S ANSWER TO BLOC POLITICS . 74 3 POLITICS OF FEAR AND TOTAL NATIONAL DEFENSE . 133 4 TITO’S TWILIGHT AND THE FEAR OF UNRAVELING . 180 5 CONCLUSION: YUGOSLAVIA AND THE LEGACY OF THE COLD WAR . 245 EPILOGUE: THE TRIUMPH OF FEAR. 254 APPENDIX A: LIST OF KEY LCY OFFICIALS, 1958 . 272 APPENDIX B: ETHNIC COMPOSITION OF JNA, 1963 . 274 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 275 INDEX . 289 © copyright by ROBERT EDWARD NIEBUHR 2008 iii ABSTRACT THE SEARCH FOR A COMMUNIST LEGITIMACY: TITO’S YUGOSLAVIA ROBERT EDWARD NIEBUHR Supervised by Larry Wolff Titoist Yugoslavia—the multiethnic state rising out of the chaos of World War II—is a particularly interesting setting to examine the integrity of the modern nation-state and, more specifically, the viability of a distinctly multi-ethnic nation-building project. -

The Cuban Missile Crisis and Its Effect on the Course of Détente

1 THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS AND ITS EFFECT ON THE COURSE OF DÉTENTE 2 Abstract The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union began in 1945 with the end of World War II and the start of an international posturing for control of a war-torn Europe. However, the Cold War reached its peak during the events of the Cuban Missile Crisis, occurring on October 15-28, 1962, with the United States and the Soviet Union taking sides against each other in the interest of promoting their own national security. During this period, the Soviet Union attempted to address the issue of its own deficit of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles compared to the United States by placing shorter-range nuclear missiles within Cuba, an allied Communist nation directly off the shores of the United States. This move allowed the Soviet Union to reach many of the United States’ largest population centers with nuclear weapons, placing both nations on a more equal footing in terms of security and status. The crisis was resolved through the imposition of a blockade by the United States, but the lasting threat of nuclear destruction remained. The daunting nature of this Crisis led to a period known as détente, which is a period of peace and increased negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union in order to avoid future confrontations. Both nations prospered due to the increased cooperation that came about during this détente, though the United States’ and the Soviet Union’s rapidly changing leadership styles and the diverse personalities of both countries’ individual leaders led to fluctuations in the efficiency and extent of the adoption of détente. -

Peaceful Coexistence and Contemporary International Law

PEACEFUL COEXISTENCE AND CONTEMPORARY INTERNATIONAL LAW Peaceful Coexistence entered the International Law lexicon with the Sino-Indian Pancha Shila Agreement of 1954, negotiated between Chou En Lai and Jawaharlal Nehru and directed immediately to an historically long-festering territorial frontier dispute between the two neighbours in the Himalayan region. The Agreement included some postulated high-level general principles of "good neighbourliness" between the two parties which would become known as the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence and be invoked historically for their own purposes by other states unconnected to the Agreement or its original purpose: mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty; non-aggression; non-interference in internal affairs; equality and mutual advantage; and peaceful coexistence itself. These principles, arguably, were already part of the United Nations Charter, either in terms or else implicit in the Charter's Chapters VI and VII on peaceful settlement. But Chou En Lai's government was not, in 1954, seated in the United Nations and would not be until 1971, and equally arguably was therefore not legally bound by the Charter provisions. An additional attractiveness in the Pancha Shila's Five Principles was to be found in their clarity and succinctness of formulation in comparison to the Charter, and in the unequivocal character of their rejection of the use of force and their embracement of peaceful settlement. This perhaps helps explain the widespread popularity of the Five Principles and their invocation in later years in very many general International Law acts. In the wake of the de-Stalinisation campaign in the Soviet Union, new Soviet leader N.S. -

Teacher's Guide Produced and Distributed By

Cold War Teacher’s Guide Produced and Distributed by: www.MediaRichLearning.com AMERICA IN THE 20TH CENTURY: THE COLD WAR TEACHER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Materials in Unit .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Series .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Program .................................................... 3 Standards .................................................... 6 Instructional Notes .................................................... 7 Suggested Instructional Procedures .................................................... 7 Student Objectives .................................................... 7 Follow-Up Activities .................................................... 8 Answer Key .................................................... 10 Script of Video Narration .................................................... 17 Blackline Masters .................................................... 45 Media Rich Learning .................................................... 72 PAGE 2 OF 105 MEDIA RICH LEARNING AMERICA IN THE 20TH CENTURY: THE COLD WAR Materials in the Unit • The video program The Cold War • Teachers Guide This teacher's guide has been prepared to aid the teacher in utilizing materials contained within this program. In addition to this introductory material, the guide contains suggested instructional procedures for the lesson, answer keys for the activity sheets, and follow-up activities and projects for the lesson. • Blackline Masters Included -

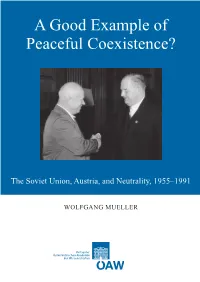

A Good Example of Peaceful Coexistence?

A Good Example of Peaceful Coexistence? The Soviet Union, Austria, and Neutrality, 1955–1991 WOLFGANG MUELLER WOLFGANG MUELLER A GOOD EXAMPLE OF PEACEFUL COEXISTENCE? THE SOVIET UNION, AUSTRIA, AND NEUTRALITY, 1955‒1991 ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE HISTORISCHE KOMMISSION ZENTRALEUROPA-STUDIEN HERAUSGEGEBEN VON ARNOLD SUPPAN UND GRETE KLINGENSTEIN BAND 15 WOLFGANG MUELLER A Good Example of Peaceful Coexistence? The Soviet Union, Austria, and Neutrality 1955‒1991 Vorgelegt von w. M. Arnold Suppan in der Sitzung am 18. Juni 2010 Cover: The Austrian chancellor, Julius Raab (r.), welcomes Nikita Khrushchev in his office, 30 June 1960, photograph by Fritz Kern, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek – Bildarchiv, FO504632_4_48. Cover design: Oliver Hunger British Library Cataloguing in Publication data. A Catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library. Die verwendete Papiersorte ist aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff hergestellt, frei von säurebildenden Bestandteilen und alterungsbeständig. Alle Rechte vorbehalten ISBN 978-3-7001-6898-0 Copyright © 2011 by Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften Druck und Bindung: Prime Rate kft., Budapest http://hw.oeaw.ac.at/6898-0 http://verlag.oeaw.ac.at Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................... 9 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 13 Soviet-Austrian relations, 1945–1955 ........................................................ -

Situation of the Soviet Revisionists’ False Support for and Betrayal on the Vietnam Issue'

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified May 21, 1965 Report from the Department of Soviet and Eastern European Affairs, 'Situation of the Soviet Revisionists’ False Support for and Betrayal on the Vietnam Issue' Citation: “Report from the Department of Soviet and Eastern European Affairs, 'Situation of the Soviet Revisionists’ False Support for and Betrayal on the Vietnam Issue',” May 21, 1965, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, PRC FMA 109-03654-02, 13-19. Translated by David Cowhig. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/118726 Summary: An article in 'Foreign Affairs Survey and Research,' a periodical produced by the Chinese Foreign Ministry, offers an in-depth critique of Soviet policy and assistance toward North Vietnam. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Henry Luce Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation May 22, 1965 Secret [handwritten: Soviet European Department] Destroy After Reading No. 139 Foreign Affairs Survey and Research May 21, 1965 Situation of the Soviet Revisionists’ False Support for and Betrayal on the Vietnam Issue 1. Political support for Vietnam is weak (1) Important documents on Vietnam are not reported, or are reported in digest, censored or piecemeal fashion. Out of the eleven important documents issued from the Vietnamese side between March 3 and April 21 (including documents of the Third Congress, Chairman Ho Chi Minh's press conference and the southern Vietnam statement), five were not mentioned at all and four were reported in digest format. Only two documents were carried in full text. Even those reports that were carried, were delayed as much as possible (generally appearing a week or so later), or in censored reports (the censored parts was the part that denounced U.S. -

Afghan-Pak Joint Peace Jirga: Possibilities and Improbabilities

IPCS No. 51, March 2008 SPECIAL REPORT Afghan-Pak Joint Peace Jirga Possibilities and Improbabilities Mariam Safi INSTITUTE OF PEACE AND CONFLICT STUDIES B 7/3 Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi110029, INDIA Tel: 91-1141652556-9; Fax: 91-11-41652560 Email: [email protected]; Web: www.ipcs.org IPCS Special Reports aim to flag issues of regional and global concern from a South Asian perspective. All IPCS Reports are peer reviewed. IPCS SPECIAL REPORT No 51, March 2008 THE AFGHAN-PAK JOINT PEACE JIRGA POSSIBILITIES AND IMPROBABILITIES MMMAAARRRIIIAAAMMM SSSAAAFFFIII Research Intern, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies An Overview In a significant move towards the The four-day peace talks, the result of an beginning of a peace process between initiative by President Hamid Karzai and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and his Pakistani counterpart, Pervez the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, leaders Musharraf on 27 September, 2006, of the two countries met in Kabul, primarily focused on threats posed by Afghanistan, from 9-12 August 2007, to Taliban, terrorism, and the narcotics discuss the declining security climate in trade in the region. both states. The resulting joint peace jirga, reflects the desire on both sides to The recommendations drawn up by the build a holistic and transparent approach delegates at the conclusion of the talks to political dialogue and cooperation. are to be followed through during the second round of peace talks expected to The Afghan-Pak Peace Jirga is based on be held in Pakistan after the January the tribal code of Pashtunwali, which is 2008 elections. not only a legal system of settling disputes, but also a code of behavior The recommendations included among and form of government, autonomous of others, making counter-terrorism the state. -

December 16, 1968 KGB Report to Central Committee on Radio Liberty Policy Guidelines

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified December 16, 1968 KGB report to Central Committee on Radio Liberty Policy guidelines Citation: “KGB report to Central Committee on Radio Liberty Policy guidelines,” December 16, 1968, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Archives of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Obtained by Michael Nelson. Translated by Volodymyr Valkov. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/121517 Summary: The KGB informs the Central Committee of RL policy guidelines concerning programs dealing with the USSR. While the first paragraph indicates “Free Europe,” the content of the note makes clear that Radio Liberty is meant. The original memorandum on which the note was based [a copy could not be located in the RFE/RL archives for comparison] was probably taken from Radio Liberty headquarters in Munich. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation Top Secret 3595[8] USSR Committee for State Security Council of Ministers 16 December 1968 No. 2789z Moscow CPSU CC Recommendations prepared by the US special services for the radio station Free Europe [sic] in December 1968 provide the following guidance regarding programs focusing on foreign and domestic policies of the USSR. Programs that deal with foreign policy should consistently underline that the development of the modern international situation was profoundly influenced by the entry of troops from the five Warsaw Pact countries into Czechoslovakia, bringing to naught the softening in relations between the East and the West that has been achieved with great difficulty in the last few years, and threatening the future of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.