The Malthusian League (1877–1927) [1]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annie Besant

(III connectTOn with MUDIE'S), SO^QHURCH ROAD, *^ WEST BRIGHTON. V r -> > -- k "J ". ^ • UCSR liBRARY -^jbn. 6vA i-^^*<»^»-^ THE080PHICAL SOCIETY, CRYSTAL PALACE LODGE. Digitized by tlie Internet Arcliive in 2007 witli funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.arcliive.org/details/anniebesantautobOObesaiala ANNIE BESANT Fii tti a l-hi tograf-)i by II. S. Mcmichsi^liii, 27, Cathcai t K^'iul, Sc^!i//i Ki'iisia^/on. Loulou. -OJME BESANT. 188; ANNIE BESANT AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY Illustrated LONDON T. FISHER UNWIN SECOND EDITIGN PREFACE. IT is a difficult thing to tell the story of a life, and yet more difficult when that life is one's own. At the best, the telling has a savour of vanity, and the only excuse for the proceeding is that the life, being an average one, reflects many others, and in troublous times like ours may give the experience of many rather than of one. And so the autobiographer does his work because he thinks that, at the cost of some unpleasantness to himself, he may throw light on some of the typical problems that are vexing the souls of his contemporaries, and perchance may stretch out a helping hand to some brother who is struggling in the darkness, and so bring him cheer when despair has him in its grip. Since all of us, men and women of this restless and eager generation—surrounded by forces we dimly see but cannot as yet understand, discontented with old ideas and half afraid of new, greedy for the material results of the knowledge brought us by Science but looking askance at her agnosticism as regards the soul, fearful of superstition but still more fearful of atheism, turning from the husks of out- grown creeds but filled with desperate hunger foi 6 PREFACE. -

Schwartz, Infidel Feminism (2013)

6 Freethought and Free Love? Marriage, birth control and sexual morality uestions of sex were central to Secularism. Even those Freethinkers who desperately sought respectability for the movement found Q it impossible to avoid the subject, for irreligion was irrevocably linked in the public mind with sexual license. Moreover, the Freethought movement had, since the beginning of the nineteenth century, been home to some of the leading advocates of sexual liberty, birth control and marriage reform. A complex relationship existed between these strands of sexual dissidence – sometimes conficting, at other times coming together to form a radical, feminist vision of sexual freedom. If a ‘Freethinking’ vision of sexual freedom existed, it certainly did not go uncontested by others in the movement. Nevertheless, the intellectual and political location of organised Freethought made it fertile ground for a radical re-imagining of sexualCIRCULATION norms and conduct. Te Freethought renunciation of Christianity necessarily entailed a rejection of the moral authority of the Church, particularly its role in legitimising sexual relations. Secularists were therefore required to fnd a new basis for morality, and questions of sex were at the centre of this project to establish new ethical criteria. In some cases Secularists’ rejec- tion of Christian asceticism and their emphasis on the material world could alsoFOR lead to a positive attitude to physical passions in both men and women. Te central Freethinking principle of free enquiry necessi- tated a commitment to open discussion of sexual matters, and while this ofen generated a great deal of anxiety, the majority of the movement’s leadership supported the need for free discussion. -

Religious Skepticism, Atheism, Humanism, Naturalism, Secularism, Rationalism, Irreligion, Agnosticism, and Related Perspectives)

Unbelief (Religious Skepticism, Atheism, Humanism, Naturalism, Secularism, Rationalism, Irreligion, Agnosticism, and Related Perspectives) A Historical Bibliography Compiled by J. Gordon Melton ~ San Diego ~ San Diego State University ~ 2011 This bibliography presents primary and secondary sources in the history of unbelief in Western Europe and the United States, from the Enlightenment to the present. It is a living document which will grow and develop as more sources are located. If you see errors, or notice that important items are missing, please notify the author, Dr. J. Gordon Melton at [email protected]. Please credit San Diego State University, Department of Religious Studies in publications. Copyright San Diego State University. ****************************************************************************** Table of Contents Introduction General Sources European Beginnings A. The Sixteenth-Century Challenges to Trinitarianism a. Michael Servetus b. Socinianism and the Polish Brethren B. The Unitarian Tradition a. Ferenc (Francis) David C. The Enlightenment and Rise of Deism in Modern Europe France A. French Enlightenment a. Pierre Bayle (1647-1706) b. Jean Meslier (1664-1729) c. Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach (1723-1789) d. Voltaire (Francois-Marie d'Arouet) (1694-1778) e. Jacques-André Naigeon (1738-1810) f. Denis Diderot (1713-1784) g. Marquis de Montesquieu (1689-1755) h. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) B. France and Unbelief in the Nineteenth Century a. August Comte (1798-1857) and the Religion of Positivism C. France and Unbelief in the Twentieth Century a. French Existentialism b. Albert Camus (1913 -1960) c. Franz Kafka (1883-1924) United Kingdom A. Deist Beginnings, Flowering, and Beyond a. Edward Herbert, Baron of Cherbury (1583-1648) b. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Recall to Life: Imperial Britain, Foreign Refugees and the Development of Modern Refuge, 1789-1905 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8219g6tg Author Shaw, Caroline Emily Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Recall to Life: Imperial Britain, Foreign Refugees and the Development of Modern Refuge, 1789-1905 By Caroline Emily Shaw A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Thomas W. Laqueur, Chair Professor James Vernon Professor Catherine Gallagher Professor David Lieberman Spring 2010 Recall to Life: Imperial Britain, Foreign Refugees and the Development of Modern Refuge, 1789-1905 © 2010 By Caroline Emily Shaw ABSTRACT Recall to Life: Imperial Britain, Foreign Refugees and the Development of Modern Refuge, 1789-1905 by Caroline Emily Shaw Doctor of Philosophy in History The University of California, Berkeley Professor Thomas W. Laqueur, Chair The dissertation that follows offers the first historical examination of the nineteenth-century origins of the “refugee” as a modern humanitarian and legal category. To date, scholars have tended to focus on a single refugee group or have overlooked this period entirely, acknowledging the linguistic origins of the term “refugee” with the seventeenth-century French Huguenots before skipping directly to the post-WWI period. I find that it is only through the imperial and global history of British refuge in the nineteenth century that we can understand the sources of our contemporary moral commitment to refugees. -

Autobiographical Sketches by Annie Besant

1 AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES BY ANNIE BESANT I am so often asked for references to some pamphlet or journal in which may be found some outline of my life, and the enquiries are so often couched in terms of such real kindness, that I have resolved to pen a few brief autobiographical sketches, which may avail to satisfy friendly questioners, and to serve, in some measure, as defence against unfair attack. I. On October 1st, 1847, I made my appearance in this "vale of tears", "little Pheasantina", as I was irreverently called by a giddy aunt, a pet sister of my mother's. Just at that time my father and mother were staying within the boundaries of the City of London, so that I was born well "within the sound of Bow bells". Though born in London, however, full three quarters of my blood are Irish. My dear mother was a Morris—the spelling of the name having been changed from Maurice some five generations back—and I have often heard her tell a quaint story, illustrative of that family pride which is so common a feature of a decayed Irish family. She was one of a large family, and her father and mother, gay, handsome, and extravagant, had wasted merrily what remained to them of patrimony. I can remember her father well, for I was fourteen years of age when he died. A bent old man, with hair like driven snow, splendidly handsome in his old age, hot-tempered to passion at the lightest provocation, loving and wrath in quick succession. -

"Dirty Filthy" Books on Birth Control

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 10 (2003-2004) Issue 3 William & Mary Journal of Women and Article 4 the Law April 2004 Law, Literature, and Libel: Victorian Censorship of "Dirty Filthy" Books on Birth Control Kristin Brandser Kalsem Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the First Amendment Commons Repository Citation Kristin Brandser Kalsem, Law, Literature, and Libel: Victorian Censorship of "Dirty Filthy" Books on Birth Control, 10 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 533 (2004), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmjowl/vol10/iss3/4 Copyright c 2004 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl LAW, LITERATURE, AND LIBEL: VICTORIAN CENSORSHIP OF "DIRTY FILTHY" BOOKS ON BIRTH CONTROL KRISTIN BRANDSER KALSEM* I. INTRODUCTION Feminist jurisprudence is about breaking silences. It is about identifying topics that are "unspeakable" in law and culture and raising questions about why that is. It is about exposing ways in which silencing works to regulate.' This Article presents a case study of the feminist jurisprudence of three early birth control advocates: Annie Besant, Jane Hume Clapperton, and Marie Stopes. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the subject of birth control was so taboo that serious efforts were made to keep John Stuart Mill from being buried in Westminster Abbey because of his sympathies with the idea of limiting family size.2 Despite this cultural climate, Annie Besant published a tract on birth control and defended herself in court against charges of obscene libel for doing so,' Jane Hume Clapperton advocated the use of birth control in a novel,4 and Marie Stopes wrote two runaway bestsellers on the topic and opened the first birth control clinic in England.' While the actual practice of birth control was not illegal in England, as this case study will show, it was highly dangerous to * Assistant Professor of Law, University of Cincinnati College of Law. -

7. Bradlaugh, Besant & “Fruits of Philosophy” (Origins of Secularism & the National Secular Society)

7. Bradlaugh, Besant & “Fruits of Philosophy” (Origins of secularism & the National Secular Society) Video available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RTIZotRBmEQ would only resolve matters through 0:00:16.060,0:00:20.980 hunger, pestilence, starvation and general Hi, Bob Forder here. misery. 0:00:21.000,0:00:31.220 0:01:41.920,0:01:49.740 Charles Bradlaugh, Annie Besant and He did argue that it could possibly be staved Charles Knowlton’s “Fruits of Philosophy” off by late marriage, but explicitly ruled out 0:00:31.260,0:00:40.620 When outlining Charles Bradlaugh's early 0:01:49.800,0:01:59.480 career, I made the point that to Bradlaugh the adoption of contraceptive techniques, or checks, which he regarded as immoral. 0:00:40.620,0:00:47.290 and many free-thinking NSS members 0:01:59.560,0:02:08.860 what we would call birth control Freethinkers, like Bradlaugh and Besant, were convinced by Malthus's analysis, 0:00:47.290,0:00:56.909 or family planning, and they would call 0:02:08.860,0:02:12.660 Malthusianism or Neo -Malthusianism, but not by his suggested cure, 0:00:56.909,0:01:07.280 0:02:12.660,0:02:21.980 were core seminal issues. hence their adoption of the term, The term Malthusianism derived from the in some cases, of Neo -Malthusianism. 0:01:07.280,0:01:19.020 0:02:21.980,0:02:31.120 work of the Rev, Thomas Malthus, who in In 1832, Charles Knowlton, an American 1798 had doctor, published his “Essay on the Principle of published a small pamphlet under the less Population”. -

Women's Medicine

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF MEDICINE SOCIAL HISTORIES OF MEDICINE Women’s medicine Women’s Women’s medicine highlights British female doctors’ key contribution to the production and circulation of scientific knowledge around contraception, family planning and sexual disorders between 1920 and 1970. It argues that women doctors were pivotal in developing a holistic approach to family planning and transmitting this knowledge across borders, playing a more prominent role in shaping scientific and medical knowledge than previously acknowledged. The book locates women doctors’ involvement within the changing landscape of national and international reproductive politics. Illuminating women doctors’ agency in the male-dominated field of medicine, this book reveals their practical engagement with birth control and later family planning clinics in Britain, their participation in the development of the international movement of birth control and family planning and their influence on French doctors. Drawing on a wide range of archived and published medical materials, Rusterholz sheds light on the strategies British female doctors used and the alliances they made to put forward their medical agenda and position themselves as experts and leaders in birth control and family planning research and practice. Caroline Rusterholz is a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow in the Faculty of History at the University of Cambridge Caroline Rusterholz Caroline Caroline Rusterholz Cover image: Set of 12 rubber diaphragms (Science Museum/Science & Society ISBN 978-1-5261-4912-1 Picture Library) Women’s medicine Cover design: riverdesignbooks.com Sex, family planning and British female doctors in transnational perspective, 9 781526 149121 1920–70 www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Women’s medicine SOCIAL HISTORIES OF MEDICINE Series editors: David Cantor, Elaine Leong and Keir Waddington Social Histories of Medicine is concerned with all aspects of health, illness and medicine, from prehistory to the present, in every part of the world. -

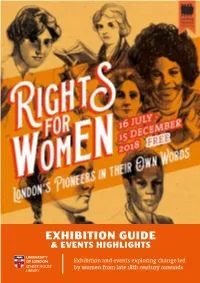

Exhibition Guide & Events Highlights

EXHIBITION GUIDE & EVENTS HIGHLIGHTS Exhibition and events exploring change led by women from late 18th century onwards Rights for Women: London’s Pioneers in their Own Words A warm welcome to Senate House Library and to Rights for Women: London’s Pioneers in their Own Words, an exhibition exploring the lives and work of over 50 of London’s female pioneers who broke barriers to drive change and establish rights for women. The exhibition of over 80 items from our collection is on display in the Convocation Hall of the iconic Senate House Library. The library houses and cares for more than two million books, 50 named special collections and over 1,800 archival collections. It’s one of the UK’s largest academic libraries focused on the arts, humanities, and social sciences and holds a wealth of primary source material from the medieval period to the modern age. I hope that you are inspired by the exhibition and accompanying events, as we give these female pioneers a platform for their words and hard-won victories. By enshrining their place in history we will ensure they continue to influence and change today’s world for the better. Dr Nick Barratt Director, Senate House Library 2 Introduction The debate around women’s rights and civil liberties gained prominence in the late eighteenth century as a consequence of social and political changes across Europe. London emerged around this time as one of the main international stages for shaping and disseminating progressive ideas on liberty and justice. This free exhibition and events season explores some of the famous and lesser known stories of over 50 women pioneers, from the late eighteenth century to present time, that used London as their platform to make their voices heard and establish equal rights for women. -

Grassroots Feminism: a Study of the Campaign of the Society for the Provision of Birth Control Clinics, 1924-1938

Grassroots feminism: a study of the campaign of the Society for the Provision of Birth Control Clinics, 1924-1938. A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities. Year of submission 2010 Clare Debenham School of Social Sciences, Faculty of Humanities List of Contents List of Contents ................................................................................................................. 2 Declaration ........................................................................................................................ 6 Copyright statement .......................................................................................................... 6 List of Abbreviations......................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... 8 Preface...............................................................................................................................9 Chapter One ...................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 10 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Reassessment of the significance of the -

A Usable Collection

A Usable Established in 1935, the International Institute of Social History is one of the world's leading research institutes on social history, holding one of the richest collections in the field. These collections and archives contain evidence of a social and economic world that affected the life and happiness of millions of people. Including material from every continent from the French Revolution to the Chinese student revolt of 1989 and the new social and protest movements of the early 2000s, the IISH collection is intensively used by researchers from all over the world. In his long and singular career, former director Jaap Collection Kloosterman has been central to the development of the IISH into a world leader in researching and collecting social and labour history. The 35 essays brought together in this volume in honour of him, A Usable give a rare insight into the history of this unique institute and the development of its collections. The contributors also offer answers to the question what it takes to devote a lifetime to collecting social Collection history, and to make these collections available for research. The essays offer a unique and multifaceted Essays in Honour of Jaap Kloosterman view on the development of social history and collecting its sources on a global scale. on Collecting Social History Edited by Aad Blok, Jan Lucassen and Huub Sanders ISBN 978 90 8964 688 0 AUP.nl A Usable Collection A Usable Collection Essays in Honour of Jaap Kloosterman on Collecting Social History Edited by Aad Blok, Jan Lucassen and -

FORGING BONDS ACROSS BORDERS Transatlantic Collaborations for Women’S Rights and Social Justice in the Long Nineteenth Century

Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Supplement 13 (2017) FORGING BONDS ACROSS BORDERS Transatlantic Collaborations for Women’s Rights and Social Justice in the Long Nineteenth Century Edited by Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson and Anja Schüler Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Washington DC Editor: Richard F. Wetzell Supplement 13 Supplement Editor: Patricia C. Sutcliffe The Bulletin appears twice and the Supplement once a year; all are available free of charge. Current and back issues are available online at: www.ghi-dc.org/bulletin To sign up for a subscription or to report an address change, please contact Ms. Susanne Fabricius at [email protected]. For editorial comments or inquiries, please contact the editor at [email protected] or at the address below. For further information about the GHI, please visit our website www.ghi-dc.org. For general inquiries, please send an e-mail to [email protected]. German Historical Institute 1607 New Hampshire Ave NW Washington DC 20009-2562 Phone: (202) 387-3355 Fax: (202) 483-3430 © German Historical Institute 2017 All rights reserved ISSN 1048-9134 Cover: Offi cial board of the International Council of Women, 1899-1904; posed behind table at the Beethoven Saal, Berlin, June 8, 1904: Helene Lange, treasurer, Camille Vidart, recording secretary, Teresa Wilson, corresponding secretary, Lady Aberdeen, vice president, May Sewall, president, & Susan B. Anthony. Library of Congress P&P, LC-USZ62-44929. Photo by August Scherl. Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Supplement 13 | 2017 Forging Bonds Across Borders: Transatlantic Collaborations for Women’s Rights and Social Justice in the Long Nineteenth Century 5 INTRODUCTION Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson and Anja Schüler NEW WOMEN’S BIOGRAPHY 17 Transatlantic Freethinker, Feminist, and Pacifi st: Ernestine Rose in the 1870s Bonnie S.