A Usable Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KRON-2010-03.Pdf

TIJDSCHRIFT HISTORISCH AMERSFOORT • JRG 12 • NR 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 K R O N I E K De smaak van de negentiende eeuw + Fons de Backer + Architect Wouter Salomons + Canon Eemland + Benjamin Cohen + Map Heijenga + Feministische bibliotheek 11 EN 12 SEPTEMBER 2010 Open Monumentendag De 24ste editie van de Open Monumentendag staat in het teken van De smaak van de 19de eeuw . Voor Amersfoort is dit een uitdagend thema, omdat de groei van onze stad pas in het laatste kwart van die eeuw goed op gang is gekomen. Toch is de architectuurgeschiedenis ook met Amersfoortse voorbeelden goed te illustreren. door MIRJAM BARENDREGT Tuinen te Amsterdam is gevraagd de ontstaansgeschie - denis van Park Randenbroek te onderzoeken. Het bureau Amersfoort heeft in de 19de eeuw vooral de aandacht doet dit aan de hand van historische tekeningen en do- getrokken met de transformatie van een aantal parken cumenten, waarop ook de aanbevelingen voor restaura - en landgoederen. Eigenaren waren uitgekeken op de geo- tie en beheer zijn gebaseerd. Mede dankzij een financië - metrische 16de- en 17de-eeuwse tuinaanleg. Zij zochten le bijdrage van de provincie Utrecht kon het verrassende naar mogelijkheden om hun bezit een meer eigentijds, dat resultaat van het onderzoek in Amersfoort Magazine wor- wil zeggen landschappelijk, aanzien te geven. Dit gold den opgenomen. In deze pocket ‘Amersfoortse parken en de smaak van de 19de eeuw’ leest u een artikel over het panorama van Amersfoort, omdat de belangstelling voor vergezichten ook in de 19de eeuw is ontstaan. Wie weet over welk vergezicht in 2110 wordt gesproken: een groen stadspark van Randenbroek tot Heiligenberg? De geschie- denis en monumenten tonen ons dat je alleen een rijk verleden kunt krijgen door een visie op de toekomst! Foto links: ingang park Randenbroek aan de Heiligenbergerweg. -

Henriette Roland Horst, Jacques Engels and the Influence of Class

‘More freedom’ or ‘more harmony’? Henriette Roland Holst, Jacques Engels and the influence of class and gender on socialists’ sexual attitudes Paper submitted to the seminar on “Labour organizations and sexuality”, Université de Bourgogne, Dijon 5 October 2001 Peter Drucker1 Sheila Rowbotham once wrote, ‘A radical critical history ... requires a continuing movement between conscious criticism and evidence, a living relationship between questions coming from a radical political movement and the discovery of aspects of the past which would have been ignored within the dominant framework.’2 Her words may apply with particular force to the history of labour organizations and sexuality. Historians can find it easier to find criticisms and questions to raise about the past than to sustain the ‘continuing movement’ required to understand the past in its own terms. The temptation is great to compare positions on sexuality taken in labour organizations in the past with positions held by historians in the present. The result can be either an idealization of sex-radical forbears or a condemnation of those whose ideas fell short of twenty-first-century enlightenment — in either case a curiously old-fashioned sort of history, which benefits little from the advances made by social historians outside ‘the dominant framework’, particularly social historians of sexuality, since the 1970s. Analyzing positions on sexuality taken in labour organizations in the past in the light of knowledge that has been accumulating about social and sexual patterns of their specific periods seems likely to be a more fruitful approach. Four different angles of attack seem particularly likely to be useful. -

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

Brochure Brill in 2015 Is Based on the Annual Report 2015

BRILL IN 2015 IN BRILL BRILL IN 2015 BRILL IN 2015 Supervisory Board Members André R. baron van Heemstra Catherine Lucet Robin Hoytema van Konijnenburg Roelf E. Rogaar (until 13 May 2015) Managing Director Herman A. Pabbruwe koninklijke brill nv Plantijnstraat 2 This brochure contains a summary po box 9000 of the consolidated financial statements 2015. 2300 pa Leiden The complete annual report 2015, including the auditor’s report, t +31 71 53 53 500 is available on www.brill.com under www.brill.com Resources/Corporate/Investor-Relations 2 BRILL IN 2015 CONTENTS Brill in 2015 2 2015 in a nutshell 6 Key Figures 7 Data per Share 8 Supervisory Board's Report 11 Supervisory Board 12 Corporate Governance 14 Remuneration Policy 15 Risk Management 21 Management Report 21 1. General Report 2015 26 2. Financial Report 2015 30 3. Personnel and Organization 33 4. 2017-2019 Strategy 34 5. Corporate Sustainability 37 Report of Stichting Administratiekantoor Koninklijke Brill 39 Report of Stichting Luchtmans 41 Summary of the Consolidated Financial Statements 2015 Other Information 46 Remuneration of Key executives 48 Profit Appropriation 49 Information for Shareholders 50 Financial Agenda 2016 51 Article Treasures of Holland, Pyotr Semenov and his Collection of Dutch Paintings By Irina Sokolova 65 Brill’s program in Art History 66 Explanation of Cover Illustration 66 Colophon 1 BRILL IN 2015 2015 IN A NUTSHELL 2015 was a challenging year due to downward trends were taken. Our Asian development plan has been that had started to develop over the last few years. stepped up, with investments made in our Singapore It was also a turning point and a year in which we office and increased sales staff for China. -

Jiddistik Heute

לקט ייִ דישע שטודיעס הנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today לקט Der vorliegende Sammelband eröffnet eine neue Reihe wissenschaftli- cher Studien zur Jiddistik sowie philolo- gischer Editionen und Studienausgaben jiddischer Literatur. Jiddisch, Englisch und Deutsch stehen als Publikationsspra- chen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Leket erscheint anlässlich des xv. Sym posiums für Jiddische Studien in Deutschland, ein im Jahre 1998 von Erika Timm und Marion Aptroot als für das in Deutschland noch junge Fach Jiddistik und dessen interdisziplinären אָ רשונג אויסגאַבעס און ייִדיש אויסגאַבעס און אָ רשונג Umfeld ins Leben gerufenes Forum. Die im Band versammelten 32 Essays zur jiddischen Literatur-, Sprach- und Kul- turwissenschaft von Autoren aus Europa, den usa, Kanada und Israel vermitteln ein Bild von der Lebendigkeit und Viel- falt jiddistischer Forschung heute. Yiddish & Research Editions ISBN 978-3-943460-09-4 Jiddistik Jiddistik & Forschung Edition 9 783943 460094 ִיידיש ַאויסגאבעס און ָ ארשונג Jiddistik Edition & Forschung Yiddish Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 לקט ִיידישע שטודיעס ַהנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Yidish : oysgabes un forshung Jiddistik : Edition & Forschung Yiddish : Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 Leket : yidishe shtudyes haynt Leket : Jiddistik heute Leket : Yiddish Studies Today Bibliografijische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografijie ; detaillierte bibliografijische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urhe- berrechtlich geschützt. -

Annual Report 2019 Koninklijke Brill Nv

1 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 KONINKLIJKE BRILL NV BRILL ANNUAL REPORT 2019 2 Supervisory Board Members Steven Perrick Catherine Lucet Robin Hoytema van Konijnenburg Theo van der Raadt Management Board Members Peter Coebergh Jasmin Lange Olivier de Vlam KONINKLIJKE BRILL NV Plantijnstraat 2 PO BOX 9000 2300 PA Leiden T +31 71 53 53 500 This annual report is available as PDF: https://brill.com/page/InvestorRelations/investor-relations BRILL ANNUAL REPORT 2019 3 CONTENTS MANAGEMENT BOARDS’ REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019 4 Introduction by the CEO 6 Company Profile 7 Key Figures 8 Data per Share 9 Shareholder Information 11 Mission, Core Values, and Corporate Strategy 13 Value Creation Process at Brill 14 Publishing Program 16 Financial Report 20 Human Resources 22 Risk Management 28 Corporate Sustainability 31 Responsibility Statement 32 Corporate Governance 35 Supervisory Board’s Report regarding the year 2019 39 Remuneration Policy and Report 44 Financial Statements for the year 2019 45 Consolidated Financial Statements 85 Company Financial Statements 97 Other Information 98 Independent Auditor’s Report 111 Supplemental Information 112 Report of Stichting Administratiekantoor Koninklijke Brill 114 Report of Stichting Luchtmans 115 About this annual report BRILL ANNUAL REPORT 2019 4 MANAGEMENT BOARD’S REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019 Introduction by the CEO We are happy to present you with our annual report for 2019, reflecting significant progress from last year. Driven by our renewed mission and strategy, we showed growth above our expectations, resulting in Brill’s best year ever in terms of revenue and EBITDA. Organically, Brill’s revenue grew by 2.5% and the total revenue growth was 3.3%. -

Nosferatu. Revista De Cine (Donostia Kultura)

Nosferatu. Revista de cine (Donostia Kultura) Título: Índices Autor/es: Nosferatu Citar como: Nosferatu (1999). Índices. Donostia Kultura. Documento descargado de: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/41162 Copyright: Reserva de todos los derechos (NO CC) La digitalización de este artículo se enmarca dentro del proyecto "Estudio y análisis para el desarrollo de una red de conocimiento sobre estudios fílmicos a través de plataformas web 2.0", financiado por el Plan Nacional de I+D+i del Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad del Gobierno de España (código HAR2010-18648), con el apoyo de Biblioteca y Documentación Científica y del Área de Sistemas de Información y Comunicaciones (ASIC) del Vicerrectorado de las Tecnologías de la Información y de las Comunicaciones de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Entidades colaboradoras: • • lndice onomástico Adorée, Renée: 8, 80 Davies, Marion: 21, 22 Agee, James: 41 Davis, Bette: 32 Alessandrini, Goffredo: 50 Davis, Carl: 86 Andreiev: 94 De Laurentiis, Dino: 34, 79, 88 Arto, Florence: 15, 16, 17 DeMille, Cecil B.: 6, 15 Asquith, Anthony: 28 De Robertis: 8 De Santis, Giuseppe: 38 Baldelli, Pío: 13 De Sica, Vittorio: 8, 9 Barahona, Fernando: 45, 50 Del Río, Dolores: 25 Bardem, Juan Antonio: 45 Delahaye, Michael: 13, 36 Barrymore, Lionel: 26, 74 Delgado, Manuel: 53, 58 Barthes, Roland: 61 Dickinson, Emily: 41 Bazin, André: 9, 13 Dieterle, Wil!iam: 30, 73 Beauchamp, D.D.: 74 Donat, Robert: 28 , 65 Beery, Wallace: 11, 12, 25, 36,91 Donen, Stanley: 22 Berge, Catherine: 12 Donskoi, Mark: 38 Bergman, Andrew: -

Rudolf Rocker Papers 1894-1958 (-1959)1894-1958

Rudolf Rocker Papers 1894-1958 (-1959)1894-1958 International Institute of Social History Cruquiusweg 31 1019 AT Amsterdam The Netherlands hdl:10622/ARCH01194 © IISH Amsterdam 2021 Rudolf Rocker Papers 1894-1958 (-1959)1894-1958 Table of contents Rudolf Rocker Papers...................................................................................................................... 4 Context............................................................................................................................................... 4 Content and Structure........................................................................................................................4 Access and Use.................................................................................................................................5 Allied Materials...................................................................................................................................5 Appendices.........................................................................................................................................6 INVENTAR........................................................................................................................................ 8 PRIVATLEBEN............................................................................................................................ 8 Persönliche und Familiendokumente................................................................................. 8 Rudolf Rocker..........................................................................................................8 -

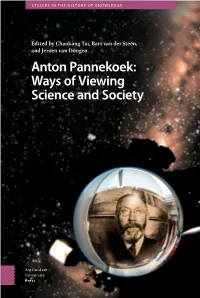

Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF KNOWLEDGE Tai, Van der Steen & Van Dongen (eds) Dongen & Van Steen der Van Tai, Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Ways of Viewing ScienceWays and Society Anton Pannekoek: Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Studies in the History of Knowledge This book series publishes leading volumes that study the history of knowledge in its cultural context. It aspires to offer accounts that cut across disciplinary and geographical boundaries, while being sensitive to how institutional circumstances and different scales of time shape the making of knowledge. Series Editors Klaas van Berkel, University of Groningen Jeroen van Dongen, University of Amsterdam Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: (Background) Fisheye lens photo of the Zeiss Planetarium Projector of Artis Amsterdam Royal Zoo in action. (Foreground) Fisheye lens photo of a portrait of Anton Pannekoek displayed in the common room of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy. Source: Jeronimo Voss Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 434 9 e-isbn 978 90 4853 500 2 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462984349 nur 686 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

The Rise of the Labour Party in East London 1880-1924

An Analysis of the Rise of the Labour Party in East London, c 1880-1924 Stephen J Mann 2012 Supervisor: John Callaghan A dissertation presented in the University of Salford in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Politics 1 Contents 3. Abbreviations 4. Acknowledgments 5. Introduction 7. Chapter 1: What was the East End like and how did the people vote before Labour? 15. Chapter 2: Working Class representation, Socialism and the London electoral system. How successful was the Labour Movement in getting people elected before 1900 and what was the system in which they fought? 24. Chapter 3: What factors led Labour towards victory in London after the war? 37. Conclusion 39. Bibliography 2 Abbreviations BSP - British Socialist Party CofE - Church of England FJPC - Foreign Jews Protection League ILP - Independent Labour Party LCC - London County Council LLP - London Labour Party LTC - London Trades Council NSP - National Socialist Party SDF - Social Democratic Federation 3 Acknowledgments Throughout the writing of this dissertation I have received a great deal of support from John Callaghan and the British Library alongside support from the Working Class Movement Library and Labour Heritage. Their contribution has been invaluable in the research and writing of this piece. As well as their support I would also like to thank the Office of Jim Fitzpatrick and the staff at Strangers Bar for offers of guidance and support, which although coming at a very late stage when the bulk of the work had been completed gave me the motivation to push me over the finish line. Finally, I would also like to pay tribute to my Great Grandfathers Harry E.C Webb OBE and Charles "Barlow" Mann who both played an important role in some of the events that are documented, without their involvement there would have been no interest in this period for me to even consider writing about it. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term.