The Changing Face of Money: Preferences for Different Payment Forms in Ghana and Zambia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Dialects

African Dialects • Adangme (Ghana ) • Afrikaans (Southern Africa ) • Akan: Asante (Ashanti) dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Fante dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Twi (Akwapem) dialect (Ghana ) • Amharic (Amarigna; Amarinya) (Ethiopia ) • Awing (Cameroon ) • Bakuba (Busoong, Kuba, Bushong) (Congo ) • Bambara (Mali; Senegal; Burkina ) • Bamoun (Cameroons ) • Bargu (Bariba) (Benin; Nigeria; Togo ) • Bassa (Gbasa) (Liberia ) • ici-Bemba (Wemba) (Congo; Zambia ) • Berba (Benin ) • Bihari: Mauritian Bhojpuri dialect - Latin Script (Mauritius ) • Bobo (Bwamou) (Burkina ) • Bulu (Boulou) (Cameroons ) • Chirpon-Lete-Anum (Cherepong; Guan) (Ghana ) • Ciokwe (Chokwe) (Angola; Congo ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Mauritian dialect (Mauritius ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Seychelles dialect (Kreol) (Seychelles ) • Dagbani (Dagbane; Dagomba) (Ghana; Togo ) • Diola (Jola) (Upper West Africa ) • Diola (Jola): Fogny (Jóola Fóoñi) dialect (The Gambia; Guinea; Senegal ) • Duala (Douala) (Cameroons ) • Dyula (Jula) (Burkina ) • Efik (Nigeria ) • Ekoi: Ejagham dialect (Cameroons; Nigeria ) • Ewe (Benin; Ghana; Togo ) • Ewe: Ge (Mina) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewe: Watyi (Ouatchi, Waci) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewondo (Cameroons ) • Fang (Equitorial Guinea ) • Fõ (Fon; Dahoméen) (Benin ) • Frafra (Ghana ) • Ful (Fula; Fulani; Fulfulde; Peul; Toucouleur) (West Africa ) • Ful: Torado dialect (Senegal ) • Gã: Accra dialect (Ghana; Togo ) • Gambai (Ngambai; Ngambaye) (Chad ) • olu-Ganda (Luganda) (Uganda ) • Gbaya (Baya) (Central African Republic; Cameroons; Congo ) • Gben (Ben) (Togo -

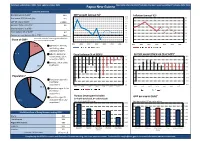

Papua New Guinea

Factsheet updated April 2021. Next update October 2021. Papua New Guinea Most data refers to 2019 (*indicates the most recent available) (~indicates 2020 data) Economic Overview Nominal GDP ($US bn)~ 23.6 GDP growth (annual %)~ 16.0 Inflation (annual %)~ 8.0 Real annual GDP Growth (%)~ -3.9 14.0 7.0 GDP per capita ($US)~ 2,684.8 12.0 10.0 6.0 Annual inflation rate (%)~ 5.0 8.0 5.0 Unemployment rate (%)~ - 6.0 4.0 4.0 Fiscal balance (% of GDP)~ -6.2 2.0 3.0 Current account balance (% of GDP)~ 0.0 13.9 2.0 -2.0 Due to the method of estimating value added, pie 1 1.0 Share of GDP* chart may not add up to 100% -4.0 1 -6.0 0.0 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 1 17.0 Agriculture, forestry, 1 and fishing, value added (% of GDP) 1 41.6 Industry (including Fiscal balance (% of GDP)~ Current account balance (% of GDP)~ 1 construction), value 0.0 40.0 1 added (% of GDP) -1.0 30.0 1 Services, value added -2.0 20.0 1 36.9 (% of GDP) -3.0 10.0 1 -4.0 0.0 1 -5.0 -10.0 Population*1 -6.0 -20.0 1 3.5 Population ages 0-14 -7.0 -30.0 1 (% of total population) -8.0 -40.0 1 35.5 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 Population ages 15-64 1 (% of total 1 population) 1 Human Development Index Population ages 65 GDP per capita ($US)~ (1= highly developed, 0= undeveloped) 61.0 1 and above (% of total Data label is global HDI ranking Data label is global GDP per capita ranking 1 population) 0.565 3,500 1 0.560 3,000 1 2,500 0.555 World Bank Ease of Doing Business ranking 2020 2,000 0.550 Ghana 118 1,500 0.545 The Bahamas 119 1,000 Papua New Guinea 120 0.540 500 153 154 155 156 157 126 127 128 129 130 Eswatini 121 0.535 0 Cameroon Pakistan Papua New Comoros Mauritania Vanuatu Lebanon Papua New Laos Solomon Islands Lesotho 122 Guinea Guinea 1 is the best, 189 is the worst UK rank is 8 Compiled by the FCDO Economics and Evaluation Directorate using data from external sources. -

Ghana, Lesotho, and South Africa: Regional Expansion of Water Supply in Rural Areas

Ghana, Lesotho, and South Africa: Regional Expansion of Water Supply in Rural Areas Water, sanitation, and hygiene are essential for achieving all the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and hence for contributing to poverty eradication globally. This case study contributes to the learning process on scaling up poverty reduction by describing and analyzing three programs in rural water and sanitation in Africa: the national rural water sector reform in Ghana, the national water and sanitation program in South Africa, and the national sanitation program in Lesotho. These national programs have made significant progress towards poverty elimination through improved water and sanitation. Although they are all different, there are several general conclusions that can validly be drawn from them: · Top-level political commitment to water and sanitation, sustained consistently over a long time period, is critically important to the success of national sector programs. · Clear legislation is necessary to give guidance and confidence to all the agencies working in the sector. · Devolution of authority from national to local government and communities improves the accountability of water and sanitation programs. · The involvement of a wide range of local institutions—social, economic, civil society, and media — empowers communities and stimulates development at the local scale. · The sensitive, flexible, and country-specific support of external agencies can add significant momentum to progress in the water and sanitation sector. Background and context Over the past decade, the rural water and sanitation sector in Ghana has been transformed from a centralized supply-driven model to a system in which local government and communities plan together, communities operate and maintain their own water services, and the private sector is active in providing goods and services. -

Greening the Recovery in Ghana and Zambia Climate Change Is One of the Most Pressing Global Challenges

INSTITUTE OF SUSTAINABLE RESOURCES Greening the Recovery in Ghana and Zambia Climate change is one of the most pressing global challenges. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, action is needed to reduce global carbon emissions to net-zero by the middle of this century. Whilst Covid-19 has led to temporary reductions in emissions, the wider economic and social impacts of the pandemic risk slowing down or derailing action on climate change. This project focuses on the opportunities for integrating economic recovery and climate change policies in Ghana and Zambia. Both countries have been affected significantly by the pandemic. Reported numbers of infections and deaths are low when compared to rates in many developed economies. However, the economic impacts have been severe – for example, due to lower demand for commodities they export such oil and copper. Summary of NDC emissions targets The research team from the UK, Ghana and Zambia is Primary energy mix (2018) workingGreenhouse with gas governmentsemissions and other stakeholders to (million tonnes of CO2 equivalent) develop80 detailed plans for a low carbon recovery. This includes revisions to Ghana and Zambia’s national climate change70 strategies, known as Nationally Determined 80 Contributions (NDCs). The emissions targets included in Zambia 60 70 their first NDCs, submitted in 2015/16, are summarised Ghana below.50 They include more ambitious conditional targets 60 that depend on international assistance. Zambia 40 Ghana 50 12.6mtoe The research will explore how both countries could go 9.9mtoe 30 40 even further, and what policy options and investments could20 deliver them. This includes options for meeting 30 growing energy demand from low carbon sources rather 10 20 than fossil fuels, and the extent to which these plans could0 also help to achieve universal access to electricity. -

Agreement Between South Africa and Ghana

CONVENTION BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME AND ON CAPITAL GAINS Preamble The Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Republic of Ghana desiring to conclude a Convention for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on income and on capital gains, Have agreed as follows: Article 1 Persons Covered This Convention shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States. Article 2 Taxes Covered 1. This Convention shall apply to taxes on income and on capital gains imposed on behalf of a Contracting State or of its political subdivisions, irrespective of the manner in which they are levied. 2. There shall be regarded as taxes on income and on capital gains all taxes imposed on total income, and on total capital gains, or on elements of income or on elements of capital gains, including taxes on gains from the alienation of movable or immovable property and taxes on the total amounts of wages and salaries paid by enterprises. 3. The existing taxes to which the Convention shall apply are: (a) in Ghana: (i) the income tax; and (ii) the capital gains tax; (hereinafter referred to as “Ghana tax”); and (b) in South Africa: (i) the normal tax; (ii) the secondary tax on companies; and (iii) the withholding tax on royalties; (hereinafter referred to as “South African tax”). -

Policy Requirements for Diaspora Engagement: the Case of Zambia: Migration and Transnationalism: Opportunities and Challenges (2

Policy Requirements for Diaspora Engagement: The case of Zambia Paul Lupunga Ministry of Finance and National Planning ZAMBIA Contents • Background Scenario –Zambia • Status – Diaspora Engagement Policies • Policy Opportunities and Threats for Zambia Background Scenario – Zambia • Location: Central/Southern Africa • Population: 12‐13 million • Poverty levels: ≈ 60 % • GDP Growth: 6‐8 % • Aid flows: 2009 ODA $300m • Remittance estimates: $70‐80m • Diaspora location: UK, USA, Canada, Australia, Southern African subcontinent, Global. Diaspora Engagement Policies • Dual citizenship (Parliament, NCC, President) • Investment promotion (Development Agency) • Census (Dept. of Registration, CSO) • Land allocation facilitation (Ministry of Lands, Ministry of Local Government) • Skilled labour recruitment (Ministry of Labour) • Remittance transmission (Bank of Zambia, Stock Exchange, private banks) • Consular assistance/ facilitation (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) Types of Diaspora Engagement Policy Capacity Building Extending Extending obligations Rights Symbolic Institution Political Investment Policies and Nation Building Incorpor- lobby promotion Building ation symbols and rhetoric Inclusive Cu S networks Building International Consular and consultative bodies Special concessions Dual Nationality Em services Tourism Mandatory payments Zones Economic Special capture** FDI for Remittance programmes transfer Knowledge Promoting Expat lobby M Conference andconventions agency Ministerial level bureaucracy Dedicated M h o us ap l ni tu t r in bassy to r a e g rin l Pr t m u rn t g ed o vot e m o i ff a ot in o vo & r i g * o ts t PR n e a n d in duct i o n Uganda Kenya Nigeria Ghana Zambia Adapted from Gamlen, 2006, p.5, *In both Uganda and Zambia in 2009 Dual Nationality was still in the stages of constitutional amendment although the provision for those amendments had been agreed. -

IOM Ghana Refugee Resettlement - West and Central Africa

INFO SHEET IOM Ghana Refugee Resettlement - West and Central Africa N E W S L E T T E R/ S I T R E P Children wait for their connecting flight at the airport in Newark, USA. © IOM 2013 United States Refugee Admission Programme (USRAP) Founded in 1951 to assist in the resettlement of IOM Ghana serves as the regional hub for both services Europeans displaced in the aftermath of World War II, and covers the following countries: IOM has provided essential services in support of refugee Country Operations Medical resettlement operations for over six decades. In the last Benin Yes Yes decade alone, IOM has organized resettlement Burkina Faso Yes Yes movements of 892,243 refugees from 186 locations Cameroon Yes Yes around the world. In West and Central Africa, the main Cape Verde Yes Yes destination country for refugee resettlement is the United Central African Republic Yes Yes States. Chad Yes Yes Congo Yes Yes In West and Central Africa, IOM provides the following Congo, Dem. Republic Yes Yes resettlement services under the USRAP: Movement Management and Operations Côte d’Ivoire Yes Yes Health Assessments and Travel Health Assistance Equatorial Guinea Yes Yes Gabon Yes Yes Gambia Yes Yes Ghana Yes Yes Guinea Yes Yes Guinea Bissau Yes Yes Liberia Yes Yes Mali Yes Yes Mauritania Yes Yes Niger Yes Yes Nigeria Yes Yes Senegal Yes Yes Sierra Leone Yes Yes Above: Refugees ready to board their resettlement flight in Togo Yes Yes Amsterdam, Netherlands. © IOM 2013 1 INFO SHEET Movement Management and Operations Part of IOM’s core mandate is to arrange safe and orderly Main nationalities resettled: movements for refugees and vulnerable migrants. -

Ghana South Africa Uganda

Connecting the Globe: The Africa Initiative Appendix 4 THE TELECOMMUNICATIONS SECTORS IN GHANA, SOUTH AFRICA AND UGANDA Ghana Ghana sold an equity stake of 30% and management control of the state’s sole service provider and licensed a second national operator in order to facilitate private-sector-led expansion of telecommunications infrastructure and services nationwide. The National Communications Authority Act of 1996, which went into effect in 1997, created Ghana’s regulator, the Ghana National Communications Authority (GNCA). The regulator reports to the Ministry of Transport and Communications. GNCA is financed by license fees, spectrum fees and funds from parliament. The responsibilities of GNCA include licensing, number planning, tariff approval and establishing licensing fees together with the sector ministry, interconnection rates together with the sector ministry and the operator, technical standards, frequency allocation, type approval, and service quality monitoring. Ghana has full competition in cellular services, and duopolies in local, domestic long distance and international services. Ghana is a WTO member that has signed the Basic Telecom Services Agreement. South Africa The separation of Posts and Telecom occurred in 1991 with the formation of Telkom. The Telecommunications Act, Act 103 of 1996 created an independent regulator, the South African Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (SATRA). The policy maker is the Ministry for Posts, Telecommunications, and Broadcasting and the head of SATRA reports to Ministry of Communications. SATRA is financed by parliamentary appropriations and its responsibilities include licensing, number planning, tariff approval, technical standards, frequency allocation, type approval, monitoring service quality and establishing license fees. South Africa has a monopoly in basic telecommunications services, a duopoly in cellular services. -

Region Brochure Africa

Structured planning Africa Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Morocco, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Tunisia, Zambia Structured planning Thanks to its impressive growth potential, Africa is becoming an increasingly attractive investment destination. Many African states currently show a stable political situation, positively affecting the development of pro- mising economic potentials. Investors are thus likely to explore extraordinary chances for sustainable business opportunities in fu- ture-oriented fields like e.g. renewable ener- gies, automotive industry, consumer goods, agriculture, tourism and infrastructure. Our team is committed to working with you to understand your requirements, developing a carefully crafted market entry strategy and thereafter successfully imple- menting your strategy. Rödl & Partner 2 Our presence in Africa Africa is a booming market that European inves - tors are rediscover- ing because of the unique growth opportunities it offers. Over the last few years countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, Angola, Ethiopia and Ke- nya have featured as some of the world‘s most attractive fastgrowing economies. Driving forces behind the high growth rates are the politi- cal stability of many countries (particularly in SubSaharan Africa), a rapidly growing middle class and its demand for European manufac- tured consumer goods, technological „leapfrogging“, the enormous investment needs for infrastructure projects as well as for the ma- nufacturing sector, housing /urban development and renewable ener- gies. This new growth is a departure from the traditionally strong re- sources sector. Progressive regionalization and the increasing collabora- tion between economic areas across the continent will make African markets even more attractive to investors. Investments are especially needed in infrastructure. -

Central African Republic Report of the Secretary-Gen

United Nations S/2020/545 Security Council Distr.: General 16 June 2020 Original: English Central African Republic Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 2499 (2019), the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) until 15 November 2020 and requested me to report on its implementation every four months. The present report provides an update on major developments in the Central African Republic since the previous report of 14 February 2020 (S/2020/124), including the impact of the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which was officially declared in the Central African Republic on 14 March. II. Political situation Political developments 2. The political environment was marked by increased mobilization ahead of the presidential and legislative elections scheduled for December 2020, contributing to tensions between political stakeholders. The Special Representative of the Secretary- General for the Central African Republic and Head of MINUSCA, Mankeur Ndiaye, with his good offices and political facilitation mandate, engaged with national stakeholders and international partners to encourage constructive and inclusive political dialogue to preserve fragile gains. 3. On 11 February, 14 opposition parties formed the Coalition de l’opposition démocratique with the proclaimed objective of ensuring free, fair, inclusive and timely elections. The coalition includes the parties Union pour le renouveau centrafricain of the former Prime Minister, Anicet-Georges Dologuélé; the Kwa Na Kwa of the former President, François Bozizé; the Convention républicaine pour le progrès social of the former Prime Minister, Nicolas Tiangaye; the Chemin de l’espérance of the former President of the National Assembly, Karim Meckassoua; and the Be Africa Ti E Kwe of the former Prime Minister, Mahamat Kamoun. -

Retailers and Wholesalers of African Natural Products: Case Studies

New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station P-15009-2-06 November 2006 A Comparison of Wholesaler/Retailer Business Characteristics of Natural Products between Ghana and Rwanda Ramu Govindasamy James Simon Venkat Puduri H. Rodolfo Juliani Juliana Asante-Dartey Hanson Arthur Bismarck Diawuo Dan Acquaye Nicholas Hitimana Department of Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics Rutgers Cooperative Extension New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station Cook College Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901 A Comparison of Wholesaler/Retailer Business Characteristics of Natural Products between Ghana and Rwanda Ramu Govindasamy James Simon Venkat Puduri H. Rodolfo Juliani Juliana Asante-Dartey Hanson Arthur Bismarck Diawuo Dan Acquaye Nicholas Hitimana Ramu Govindasamy is Associate Professor, Dept. of Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901; James Simon is Professor, Dept. of Plant Sciences and New Use Agriculture and Natural Plant Products Program Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA; Venkat Puduri is Post Doctoral Associate, Dept. of Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901; H. Rodolfo Juliani is Research Associate, Dept. of Plant Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901; Juliana Asante-Dartey , Hanson Arthur, Bismarck Diawuo and Dan Acquaye, ASNAPP-Ghana, P.M.B. (18) Kanda, Accra, H/NO C 205/29, Mempeasem, East Legon, Accra, Ghana; Nicholas Hitimana, ASNAPP-Rwanda, PO Box 6052, Kigali, Rwanda. Correspondence Address Ramu Govindasamy, Associate Professor Department of Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics Cook College Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey 55 Dudley Road, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901-8520 Phone: (732) 932-9171 ext. 254 Acknowledgements We thank both the Ghanaian and Rwandan individuals with whom we interviewed for sharing their information with us. -

RP Agricultural Innovations Ghana the Gambia

Agricultural Innovations for Climate Change Adaptation and Food Security in Africa: The Cases of Ghana and The Gambia African Technology Policy Studies Network RESEARCH PAPER | No. 11 Gordon Akon-Yamga Paul Boadu Beatrice Darko Obiri Joyce Amoako Fatou Janha Mboob Agricultural Innovations for Climate Change Adaptation and Food Security in Africa: The Cases of Ghana and The Gambia Gordon Akon-Yamga Beatrice Darko Obiri Paul Boadu Joyce Amoako Fatou Janha Mboob Agricultural Innovations for Climate Change Adaptation and Food Security in Africa: The Cases of Ghana and The Gambia Gordon Akon-Yamga Beatrice Darko Obiri Paul Boadu Joyce Amoako Fatou Janha Mboob Table of Contents Acknowledgement 4 Executive Summary 5 List of Acronyms & Abbreviations 9 1. Introduction 10 2. Literature Review 13 3. Study Area 19 4. Methodology 21 5. Results 25 6. Conclusions & Recommendations 52 The African Technology Policy Studies Network (ATPS) is a multi- Bibliography 53 disciplinary network of researchers, private sector actors and policy makers promoting the generation, dissemination, use and mastery of science, technology and innovation (ST&I) for African development, environmental sustainability and global inclusion. ATPS intends to achieve its mandate through research, capacity building and training, science communication/dissemination and sensitization, participatory multi-stakeholder dialogue, knowledge brokerage, and policy advocacy. Published by the African Technology Policy Studies Network P O Box 10081, 00100 GPO Nairobi Kenya 2011 Published by the African Technology Policy Studies Network ISBN: 978-9966-030-11-5 Agricultural Innovations for Climate Change Adaptation and Food Security in Africa: The Cases of Ghana and The Gambia | 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgement 4 Executive Summary 5 List of Acronyms & Abbreviations 9 1.