"Brain Drain" of the Best and Brightest: Microeconomic Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnationalism and Expatriate Political Engagement: the Case of the Italian and French Voting in Australia

Transnationalism and expatriate political engagement: The case of the Italian and French voting in Australia Dr Maryse Helbert Maryse joined Melbourne University and completed her PhD in international Relations and Political Economy in 2016. Prior to that, she was an advocate for and research on women’s participation in politics and decision-making for over a decade. She is now focusing on teaching and research in the fields of political Science and International Relations. Assoc. Professor Bruno Mascitelli Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne Prior to joining Swinburne University of Technology, Bruno was employed by the Australian Consulate in Milan, Italy where he spent 18 years. In 1997 he joined Swinburne University and has since focused his teaching and research in areas related to European Studies. This has included four books on Italy and its expatriate community abroad looking at expatriate voting in particular. He is President of the European Studies Association in Australia. Abstract The aim of this paper is to provide an appreciation and analysis of the expatriate connectivity of Italian and the French citizens from their place of residency in Australia through their respective elections in their home country election. Specifically, the paper will examine the cases of Italians in Australia voting in the 2013 Italian elections and equally that of French citizens in Australia voting in the French Presidential and the following Legislative Elections in 20171. The paper examines the voting patterns there might be between those voting in the home country (Italy and France) and those voting in external electoral colleges in this case the relevant Australian college. -

American Literary Expatriates in Europe Professor Glenda R. Carpio Ca’ Foscari-Harvard Summer School 2017 TF: Nicholas Rinehart

American Literary Expatriates in Europe Professor Glenda R. Carpio Ca’ Foscari-Harvard Summer School 2017 TF: Nicholas Rinehart This course explores the fiction and travel literature produced by American writers living in Europe, from the late 19th century to the present. In the course of this period Europe becomes the battlefield for two bloody World Wars as well as the site of a museum past while the USA assumes a dominant role on the world stage. American writers living and traveling in Europe reflect on these shifts and changes while also exploring the various forms of freedom and complex set of contradictions that expatriate life affords. We will focus on American literature set in Europe with readings that include but are not limited to essays, travelogues, poems, novellas, novels, and short stories. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Active participation in the course; two critical essays (5-7 pages) and a third (also 5-7 pages) that may be creative or a revision of a previous assignment (see below); and an in-class presentation. Class Presentations: Throughout the semester, I will ask you to prepare short class presentations of no more than 10 minutes (NB: you will be timed and stopped if you go over the limit) based on close readings of particular passages of the texts we read. Presentations may be done individually or in pairs. You will receive more information on this method as the semester develops. Critical Essays: Two of the three essays required for this class should be critical explorations of texts and/or topics covered in class. These should be based on close analyses of specific passages and may include the secondary recommended material indicated in the syllabus. -

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

Brain Drain” of the Best and Brightest: Microeconomic Evidence from Five Countries

Discussion Paper Series CDP No 18/10 The Economic Consequences of “Brain Drain” of the Best and Brightest: Microeconomic Evidence from Five Countries John Gibson and David McKenzie Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration Department of Economics, University College London Drayton House, 30 Gordon Street, London WC1H 0AX CReAM Discussion Paper No 18/10 The Economic Consequences of “Brain Drain” of the Best and Brightest: Microeconomic Evidence from Five Countries John Gibson* and David McKenzie† * University of Waikato † World Bank Non-Technical Abstract Brain drain has long been a common concern for migrant-sending countries, particularly for small countries where high-skilled emigration rates are highest. However, while economic theory suggests a number of possible benefits, in addition to costs, from skilled emigration, the evidence base on many of these is very limited. Moreover, the lessons from case studies of benefits to China and India from skilled emigration may not be relevant to much smaller countries. This paper presents the results of innovative surveys which tracked academic high-achievers from five countries to wherever they moved in the world in order to directly measure at the micro level the channels through which high-skilled emigration affects the sending country. The results show that there are very high levels of emigration and of return migration among the very highly skilled; the income gains to the best and brightest from migrating are very large, and an order of magnitude or more greater than any other effect; there are large benefits from migration in terms of postgraduate education; most high-skilled migrants from poorer countries send remittances; but that involvement in trade and foreign direct investment is a rare occurrence. -

African Dialects

African Dialects • Adangme (Ghana ) • Afrikaans (Southern Africa ) • Akan: Asante (Ashanti) dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Fante dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Twi (Akwapem) dialect (Ghana ) • Amharic (Amarigna; Amarinya) (Ethiopia ) • Awing (Cameroon ) • Bakuba (Busoong, Kuba, Bushong) (Congo ) • Bambara (Mali; Senegal; Burkina ) • Bamoun (Cameroons ) • Bargu (Bariba) (Benin; Nigeria; Togo ) • Bassa (Gbasa) (Liberia ) • ici-Bemba (Wemba) (Congo; Zambia ) • Berba (Benin ) • Bihari: Mauritian Bhojpuri dialect - Latin Script (Mauritius ) • Bobo (Bwamou) (Burkina ) • Bulu (Boulou) (Cameroons ) • Chirpon-Lete-Anum (Cherepong; Guan) (Ghana ) • Ciokwe (Chokwe) (Angola; Congo ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Mauritian dialect (Mauritius ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Seychelles dialect (Kreol) (Seychelles ) • Dagbani (Dagbane; Dagomba) (Ghana; Togo ) • Diola (Jola) (Upper West Africa ) • Diola (Jola): Fogny (Jóola Fóoñi) dialect (The Gambia; Guinea; Senegal ) • Duala (Douala) (Cameroons ) • Dyula (Jula) (Burkina ) • Efik (Nigeria ) • Ekoi: Ejagham dialect (Cameroons; Nigeria ) • Ewe (Benin; Ghana; Togo ) • Ewe: Ge (Mina) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewe: Watyi (Ouatchi, Waci) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewondo (Cameroons ) • Fang (Equitorial Guinea ) • Fõ (Fon; Dahoméen) (Benin ) • Frafra (Ghana ) • Ful (Fula; Fulani; Fulfulde; Peul; Toucouleur) (West Africa ) • Ful: Torado dialect (Senegal ) • Gã: Accra dialect (Ghana; Togo ) • Gambai (Ngambai; Ngambaye) (Chad ) • olu-Ganda (Luganda) (Uganda ) • Gbaya (Baya) (Central African Republic; Cameroons; Congo ) • Gben (Ben) (Togo -

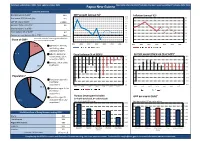

Papua New Guinea

Factsheet updated April 2021. Next update October 2021. Papua New Guinea Most data refers to 2019 (*indicates the most recent available) (~indicates 2020 data) Economic Overview Nominal GDP ($US bn)~ 23.6 GDP growth (annual %)~ 16.0 Inflation (annual %)~ 8.0 Real annual GDP Growth (%)~ -3.9 14.0 7.0 GDP per capita ($US)~ 2,684.8 12.0 10.0 6.0 Annual inflation rate (%)~ 5.0 8.0 5.0 Unemployment rate (%)~ - 6.0 4.0 4.0 Fiscal balance (% of GDP)~ -6.2 2.0 3.0 Current account balance (% of GDP)~ 0.0 13.9 2.0 -2.0 Due to the method of estimating value added, pie 1 1.0 Share of GDP* chart may not add up to 100% -4.0 1 -6.0 0.0 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 1 17.0 Agriculture, forestry, 1 and fishing, value added (% of GDP) 1 41.6 Industry (including Fiscal balance (% of GDP)~ Current account balance (% of GDP)~ 1 construction), value 0.0 40.0 1 added (% of GDP) -1.0 30.0 1 Services, value added -2.0 20.0 1 36.9 (% of GDP) -3.0 10.0 1 -4.0 0.0 1 -5.0 -10.0 Population*1 -6.0 -20.0 1 3.5 Population ages 0-14 -7.0 -30.0 1 (% of total population) -8.0 -40.0 1 35.5 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 Population ages 15-64 1 (% of total 1 population) 1 Human Development Index Population ages 65 GDP per capita ($US)~ (1= highly developed, 0= undeveloped) 61.0 1 and above (% of total Data label is global HDI ranking Data label is global GDP per capita ranking 1 population) 0.565 3,500 1 0.560 3,000 1 2,500 0.555 World Bank Ease of Doing Business ranking 2020 2,000 0.550 Ghana 118 1,500 0.545 The Bahamas 119 1,000 Papua New Guinea 120 0.540 500 153 154 155 156 157 126 127 128 129 130 Eswatini 121 0.535 0 Cameroon Pakistan Papua New Comoros Mauritania Vanuatu Lebanon Papua New Laos Solomon Islands Lesotho 122 Guinea Guinea 1 is the best, 189 is the worst UK rank is 8 Compiled by the FCDO Economics and Evaluation Directorate using data from external sources. -

THE CONCEPT of the DOUBLE JOSEPH'conrad by Werner

The concept of the double in Joseph Conrad Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bruecher, Werner, 1927- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 16:33:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318966 THE CONCEPT OF THE DOUBLE JOSEPH'CONRAD by Werner Bruecher A Thesis Snbmitted to tHe Faculty of the .' DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE OTHERS TTY OF ' ARIZONA ' STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable with out special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below ^/viz. -

Ghana, Lesotho, and South Africa: Regional Expansion of Water Supply in Rural Areas

Ghana, Lesotho, and South Africa: Regional Expansion of Water Supply in Rural Areas Water, sanitation, and hygiene are essential for achieving all the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and hence for contributing to poverty eradication globally. This case study contributes to the learning process on scaling up poverty reduction by describing and analyzing three programs in rural water and sanitation in Africa: the national rural water sector reform in Ghana, the national water and sanitation program in South Africa, and the national sanitation program in Lesotho. These national programs have made significant progress towards poverty elimination through improved water and sanitation. Although they are all different, there are several general conclusions that can validly be drawn from them: · Top-level political commitment to water and sanitation, sustained consistently over a long time period, is critically important to the success of national sector programs. · Clear legislation is necessary to give guidance and confidence to all the agencies working in the sector. · Devolution of authority from national to local government and communities improves the accountability of water and sanitation programs. · The involvement of a wide range of local institutions—social, economic, civil society, and media — empowers communities and stimulates development at the local scale. · The sensitive, flexible, and country-specific support of external agencies can add significant momentum to progress in the water and sanitation sector. Background and context Over the past decade, the rural water and sanitation sector in Ghana has been transformed from a centralized supply-driven model to a system in which local government and communities plan together, communities operate and maintain their own water services, and the private sector is active in providing goods and services. -

The Changing Face of Money: Preferences for Different Payment Forms in Ghana and Zambia

The Changing Face of Money: Preferences for Different Payment Forms in Ghana and Zambia Vivian A. Dzokoto Virginia Commonwealth University Elizabeth N. Appiah Pentecost University College Laura Peters Chitwood Counseling & Advocacy Associates Mwiya L. Imasiku University of Zambia Mobile Money (MM) is now a popular medium of exchange and store of value in parts of Africa, Latin America and Asia. As payment modalities emerge, consumer preferences for different payment tools evolve. Our study examines the preference for, and use of MM and other payment forms in both Ghana and Zambia. Our multi-method investigation indicates that while MM preference and awareness is high, scope of use is low in Ghana and Zambia. Cash remains the predominant mode of business transaction in both countries. Increased merchant acceptability is needed to improve the MM ecology in these countries. 1. INTRODUCTION The materiality of money has evolved over time, evidenced by the emergence of debit and credit cards in the twentieth century (Borzekowski and Kiser, 2008; Schuh and Stavins, 2010). Currently, mobile forms of payment are reaching widespread use in many regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, which is the fastest growing market for mobile phones worldwide (International Telecommunication Union [ITU], 2009). For example, M-Pesa is an extremely popular form of mobile payment in Kenya, possibly due to structural and cultural factors (Omwansa and Sullivan, 2012). However, no major form of money from the twentieth century has been completely phased out, as people exercise preferences for which form of money to use. Based on the evolution of payment methods, the current study explores perceptions and utilization of Mobile Money (MM) in Ghana, West Africa and in Zambia, South-Central Africa. -

Electoral Commission Code Book

ELECTORAL COMMISSION CODE BOOK REGION: A - WESTERN DISTRICT: 01 - JOMORO CONSTITUENCY: 01 - JOMORO EA NAME PS CODE POLLING STATION NAME 01 - ENOSE A010101 METH JSS WORKSHOP BLK C HALF-ASSINI A010102 PEACE INTERNATIONAL PRIM SCH COMBODIA HALF-ASSINI A010103 METH JSS BLK A HALF-ASSINI A010104 OPPOSITE GCB HALF ASSINI A010105 METH PRIM A HALF-ASSINI A010106 NREDA/SHIDO SQUARE, HALF-ASSINI A010107 METH PRIM BLK B HALF-ASSINI A010108 E. EKPALE'S SQUARE, HALF ASSINI A010109 WHAJAH'S SQUARE, HALF ASSINI A010110 ARVO'S SQUARE HALF-ASSINI A010111 P. TOBENLE'S SQUARE, HALF ASSINI Number of PS in EA = 11 02 - ADONWOZO A010201 R/C JSS BLK A HALF-ASSINI A010202 NANA AYEBIE AMIHERE PRIM SCH HALF-ASSINI A010203 CHRIST THE KING PREP, HALF ASSINI Number of PS in EA = 3 03 - AMANZULE A010301 NZEMA MAANLE PREP SCH BLK A HALF-ASSINI A010302 NZEMA MAANLE N'SERY BLK B HALF-ASSINI A010303 PUBLIC SQUARE ASUKOLO A010304A OLD JOMORO DIST. ASSEMBLY HALL, HALF ASSINI A010304B OLD JOMORO DIST. ASSEMBLY HALL, HALF ASSINI A010305 MAGISTRATE COURT, HALF ASSINI A010306 PUBLIC SQUARE, METIKA Number of PS in EA = 7 04 - EKPU A010401 D/A JSS EKPU A010402 MARKET SQUARE, EKPU A010403 R C PRIM SCH BLK A EKPU Number of PS in EA = 3 19-Sep-16 Page 1 of 1371 ELECTORAL COMMISSION CODE BOOK REGION: A - WESTERN DISTRICT: 01 - JOMORO CONSTITUENCY: 01 - JOMORO EA NAME PS CODE POLLING STATION NAME 05 - NEW TOWN A010501A D/A PRIM SCH NEWTOWN A010501B D/A PRIM SCH NEWTOWN A010502 D/A NURSERY SCH NEWTOWN A010503 D/A KG NEWTOWN WHARF Number of PS in EA = 4 06 - EFASU MANGYEA A010601 D/A -

Greening the Recovery in Ghana and Zambia Climate Change Is One of the Most Pressing Global Challenges

INSTITUTE OF SUSTAINABLE RESOURCES Greening the Recovery in Ghana and Zambia Climate change is one of the most pressing global challenges. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, action is needed to reduce global carbon emissions to net-zero by the middle of this century. Whilst Covid-19 has led to temporary reductions in emissions, the wider economic and social impacts of the pandemic risk slowing down or derailing action on climate change. This project focuses on the opportunities for integrating economic recovery and climate change policies in Ghana and Zambia. Both countries have been affected significantly by the pandemic. Reported numbers of infections and deaths are low when compared to rates in many developed economies. However, the economic impacts have been severe – for example, due to lower demand for commodities they export such oil and copper. Summary of NDC emissions targets The research team from the UK, Ghana and Zambia is Primary energy mix (2018) workingGreenhouse with gas governmentsemissions and other stakeholders to (million tonnes of CO2 equivalent) develop80 detailed plans for a low carbon recovery. This includes revisions to Ghana and Zambia’s national climate change70 strategies, known as Nationally Determined 80 Contributions (NDCs). The emissions targets included in Zambia 60 70 their first NDCs, submitted in 2015/16, are summarised Ghana below.50 They include more ambitious conditional targets 60 that depend on international assistance. Zambia 40 Ghana 50 12.6mtoe The research will explore how both countries could go 9.9mtoe 30 40 even further, and what policy options and investments could20 deliver them. This includes options for meeting 30 growing energy demand from low carbon sources rather 10 20 than fossil fuels, and the extent to which these plans could0 also help to achieve universal access to electricity. -

Afex #Bestsatpreponthecontinent Afex Sat Scores 2019

AFEX TEST PREP Preparing students for success in the changing world SAT SCORES 2019 THE HIGHEST POSSIBLE SAT SCORE IS 1600, 800 IN MATH 800 IN VERBAL OUT OF ALL TEST TAKERS IN THE WORLD VER NO NAME SCHOOL MATH BAL TOTAL PERCENTILE 1 SCHUYLER SEYRAM MFANTSIPIM SCHOOL 780 760 1540 TOP 1% 2 CHRISTOPHER OHRT LINCOLN COMMNUNITY SCHOOL 800 730 1530 TOP 1% 3 ADAMS ANAGLO ACHIMOTA SCHOOL 800 730 1530 TOP 1 % 4 JAMES BOATENG PRESEC, LEGON 800 730 1530 TOP 1% 5 GABRIEL ASARE WEST AFRICAN SENIOR HIGH 760 760 1520 TOP 1% 6 BLESSING OPOKU T. I. AHMADIYYA SNR. HIGH SCH 760 760 1520 TOP 1% 7 VICTORIA KIPNGETICH BROOKHOUSE INT’L SCH. - KENYA 760 750 1510 TOP 1% 8 EMMANUEL OPPONG PREMPEH COLLEGE 740 770 1510 TOP 1% 9 KWABENA YEBOAH ASARE S.O.S COLLEGE 780 730 1510 TOP 1% 10 SANDRA MWANGI ALLIANCE GIRLS' HIGH SCH.- KENYA 770 740 1510 TOP 1% 11 GEORGINA OMABOE CATE SCHOOL,USA 750 760 1510 TOP 1% 12 KUEI YAI BROOKHOUSE INT’L SCH. - KENYA 800 700 1500 TOP 1% 13 MICHAEL AHENKORA AKOSOMBO INTERNATIONAL SCH. 770 730 1500 TOP 1 % 14 KELVIN SARPONG S.O.S. COLLEGE 800 700 1500 TOP 1 % 15 AMY MIGUNDA ST ANDREW'S TURI - KENYA 790 710 1500 TOP 2 % 16 DESMOND ABABIO ST THOMAS AQUINAS 800 700 1500 TOP 1% 17 ALVIN OMONDI BROOKHOUSE INT’L SCH. - KENYA 790 700 1490 TOP 2 % 18 NANA K. OWUSU-MENSAH PRESEC LEGON 790 700 1490 TOP 2 % 19 CHARITY APREKU TEMA INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL 710 780 1490 TOP 2 % 20 LAURA LARBI-TIEKU GHANA CHRISTIAN INTERNATIONAL 770 720 1490 TOP 2 % 21 REUBEN AGOGOE ST THOMAS AQUINAS 790 700 1490 TOP 2 % 22 WILMA TAY GHANA NATIONAL COLLEGE 740 750 1490 TOP 2 % 23 BRANDON AMBETSA BROOKHOUSE INT’L SCH.