Ghana Country Development Cooperation Strategy 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home Office, United Kingdom

GHANA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT APRIL 2002 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM CONTENTS I. Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.5 II. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 Economy 2.3 III. History 3.1 - 3.2 IV. State Structures The Constitution 4.1 - 4.3 Political System 4.4 - 4.8 Judiciary 4.9 - 4.15 Military 4.16 (i) National Service 4.17 Internal Security 4.18 - 4.22 Legal Rights/Detention 4.23 - 4.24 Prisons and Prison conditions 4.25 - 4.30 Medical Services 4.31 - 4.38 Educational System 4.39 - 4.41 V. Human Rights V.A Human Rights Issues Overview 5.1 - 5.4 Freedom of Speech and the Media 5.5 - 5.11 Freedom of Religion 5.12 - 5.19 Freedom of Assembly & Association 5.20 - 5.25 Employment Rights 5.26 - 5.28 People Trafficking 5.29 - 5.34 Freedom of Movement 5.35 - 5.36 V.B Human Rights - Specific Groups Women 5.37 - 5.43 (i) Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 5.44 - 5.45 (ii) The Trokosi system 5.46 - 5.48 Children 5.49 - 5.55 Ethnic Groups 5.56 - 5.60 Homosexuals 5.61 V.C Human Rights - Other Issues Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) 5.62 Annexes: Chronology of Events Political Organisations Prominent People References to Source Material I. Scope of Document 1.1. This assessment has been produced by the Country Information & Policy Unit, Immigration & Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2. The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. -

Migrant Health Care Practices: the Perspectives of Women Head Porters in Kumasi, Ghana

MIGRANT HEALTH CARE PRACTICES: THE PERSPECTIVES OF WOMEN HEAD PORTERS IN KUMASI, GHANA PROSPER ASAANA Bachelor of Arts, University of Ghana, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Women and Gender Studies University of Lethbridge Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada ©Prosper Asaana, 2015 MIGRANT HEALTH CARE PRACTICES: THE PERSPECTIVES OF WOMEN HEAD PORTERS IN KUMASI, GHANA PROSPER ASAANA Dr. Carol Williams Associate Professor PhD Supervisor Dr. Suzanne Lenon Associate Professor PhD Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. Jean Harrowing Associate Professor PhD Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. Carly Adams Associate Professor PhD Chair, Thesis Examination Committee ii Dedication To the hardworking Northern Ghanaian migrant women porters, for taking time off their busy schedules to share their stories of migration and health seeking with me. iii Abstract This thesis seeks understanding of how gender, as a system of power, facilitates, constraints, determines, and impacts not only women’s migration, but more significantly, women’s access to health services post migration in contemporary Ghana. Drawing on the stories of women head porters, via the application of the principles of feminist standpoint theory, I explore women porters’ experiences as deeply embedded in social and power struggles that women did not create, but yet find binding on their lives. Women porters discuss financial struggles, negative encounters with health staff, and the hurdles of dealing with the power that men exert over their decisions and actions as barriers that limit their access and utilization of health services. -

The Politics of Accountability in Ghana's National

RESEARCH BRIEFING JUNE 2016 WHEN DOES THE STATE LISTEN? 1 16 How does governmentIDS_Master Logo responsiveness come about? The politics of accountability in Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme TERENCE DARKO RESEARCH How does government responsiveness come about? BRIEFING The politics of accountability in Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme Author Terence Darko is a Researcher at Capacity Development Consult (CDC), a Ghanaian-based research and consulting firm. He has an MA in Social Policy Studies from the University of Ghana. Before joining CDC, he worked with Innovations for Poverty Action Ghana and the Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research, Ghana. His research interests include policy processes, the politics of social development, social protection, citizen participation and political accountability. Email: [email protected] Production credits Production editor: Catherine Setchell, Making All Voices Count, [email protected] Copyeditor: Karen Brock, Green Ink, [email protected] Designer: Lance Bellers, [email protected] Further reading This research briefing forms part of a wider research project called When Does the State Listen? led by the Institute of Development Studies and funded by the Making All Voices Count initiative. The other briefs from this research project are: Cassim, A. (2016) What happens to policy when policy champions move on? The case of welfare 2 in South Africa, Brighton: IDS 16 Katera, L. (2016) Why is it so hard for non-state actors to be heard? Inside Tanzania’s education policies, Brighton: IDS Loureiro, M; Cassim, A; Darko, T; Katera, L; and Salome, N. (2016) ‘When Does the State Listen?’ IDS Bulletin Vol 47 No. -

A Case Comparison of Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal

1 Democratization and Universal Health Coverage: A Case Comparison of Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal Karen A. Grépin and Kim Yi Dionne This article identifies conditions under which newly established democracies adopt Universal Health Coverage. Drawing on the literature examining democracy and health, we argue that more democratic regimes – where citizens have positive opinions on democracy and where competitive, free and fair elections put pressure on incumbents – will choose health policies targeting a broader proportion of the population. We compare Ghana to Kenya and Senegal, two other countries which have also undergone democratization, but where there have been important differences in the extent to which these democratic changes have been perceived by regular citizens and have translated into electoral competition. We find that Ghana has adopted the most ambitious health reform strategy by designing and implementing the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS). We also find that Ghana experienced greater improvements in skilled attendance at birth, childhood immunizations, and improvements in the proportion of children with diarrhea treated by oral rehydration therapy than the other countries since this policy was adopted. These changes also appear to be associated with important changes in health outcomes: both infant and under-five mortality rates declined rapidly since the introduction of the NHIS in Ghana. These improvements in health and health service delivery have also been observed by citizens with a greater proportion of Ghanaians reporting satisfaction with government handling of health service delivery relative to either Kenya or Senegal. We argue that the democratization process can promote the adoption of particular health policies and that this is an important mechanism through which democracy can improve health. -

African Dialects

African Dialects • Adangme (Ghana ) • Afrikaans (Southern Africa ) • Akan: Asante (Ashanti) dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Fante dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Twi (Akwapem) dialect (Ghana ) • Amharic (Amarigna; Amarinya) (Ethiopia ) • Awing (Cameroon ) • Bakuba (Busoong, Kuba, Bushong) (Congo ) • Bambara (Mali; Senegal; Burkina ) • Bamoun (Cameroons ) • Bargu (Bariba) (Benin; Nigeria; Togo ) • Bassa (Gbasa) (Liberia ) • ici-Bemba (Wemba) (Congo; Zambia ) • Berba (Benin ) • Bihari: Mauritian Bhojpuri dialect - Latin Script (Mauritius ) • Bobo (Bwamou) (Burkina ) • Bulu (Boulou) (Cameroons ) • Chirpon-Lete-Anum (Cherepong; Guan) (Ghana ) • Ciokwe (Chokwe) (Angola; Congo ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Mauritian dialect (Mauritius ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Seychelles dialect (Kreol) (Seychelles ) • Dagbani (Dagbane; Dagomba) (Ghana; Togo ) • Diola (Jola) (Upper West Africa ) • Diola (Jola): Fogny (Jóola Fóoñi) dialect (The Gambia; Guinea; Senegal ) • Duala (Douala) (Cameroons ) • Dyula (Jula) (Burkina ) • Efik (Nigeria ) • Ekoi: Ejagham dialect (Cameroons; Nigeria ) • Ewe (Benin; Ghana; Togo ) • Ewe: Ge (Mina) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewe: Watyi (Ouatchi, Waci) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewondo (Cameroons ) • Fang (Equitorial Guinea ) • Fõ (Fon; Dahoméen) (Benin ) • Frafra (Ghana ) • Ful (Fula; Fulani; Fulfulde; Peul; Toucouleur) (West Africa ) • Ful: Torado dialect (Senegal ) • Gã: Accra dialect (Ghana; Togo ) • Gambai (Ngambai; Ngambaye) (Chad ) • olu-Ganda (Luganda) (Uganda ) • Gbaya (Baya) (Central African Republic; Cameroons; Congo ) • Gben (Ben) (Togo -

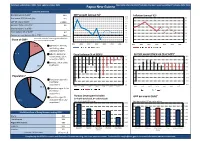

Papua New Guinea

Factsheet updated April 2021. Next update October 2021. Papua New Guinea Most data refers to 2019 (*indicates the most recent available) (~indicates 2020 data) Economic Overview Nominal GDP ($US bn)~ 23.6 GDP growth (annual %)~ 16.0 Inflation (annual %)~ 8.0 Real annual GDP Growth (%)~ -3.9 14.0 7.0 GDP per capita ($US)~ 2,684.8 12.0 10.0 6.0 Annual inflation rate (%)~ 5.0 8.0 5.0 Unemployment rate (%)~ - 6.0 4.0 4.0 Fiscal balance (% of GDP)~ -6.2 2.0 3.0 Current account balance (% of GDP)~ 0.0 13.9 2.0 -2.0 Due to the method of estimating value added, pie 1 1.0 Share of GDP* chart may not add up to 100% -4.0 1 -6.0 0.0 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 1 17.0 Agriculture, forestry, 1 and fishing, value added (% of GDP) 1 41.6 Industry (including Fiscal balance (% of GDP)~ Current account balance (% of GDP)~ 1 construction), value 0.0 40.0 1 added (% of GDP) -1.0 30.0 1 Services, value added -2.0 20.0 1 36.9 (% of GDP) -3.0 10.0 1 -4.0 0.0 1 -5.0 -10.0 Population*1 -6.0 -20.0 1 3.5 Population ages 0-14 -7.0 -30.0 1 (% of total population) -8.0 -40.0 1 35.5 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023 2025 Population ages 15-64 1 (% of total 1 population) 1 Human Development Index Population ages 65 GDP per capita ($US)~ (1= highly developed, 0= undeveloped) 61.0 1 and above (% of total Data label is global HDI ranking Data label is global GDP per capita ranking 1 population) 0.565 3,500 1 0.560 3,000 1 2,500 0.555 World Bank Ease of Doing Business ranking 2020 2,000 0.550 Ghana 118 1,500 0.545 The Bahamas 119 1,000 Papua New Guinea 120 0.540 500 153 154 155 156 157 126 127 128 129 130 Eswatini 121 0.535 0 Cameroon Pakistan Papua New Comoros Mauritania Vanuatu Lebanon Papua New Laos Solomon Islands Lesotho 122 Guinea Guinea 1 is the best, 189 is the worst UK rank is 8 Compiled by the FCDO Economics and Evaluation Directorate using data from external sources. -

Interest Groups, Issue Definition and the Politics of Healthcare in Ghana

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Public Policy and Administration Research www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-5731(Paper) ISSN 2225-0972(Online) Vol.4, No.6, 2014 Interest Groups, Issue Definition and the Politics of Healthcare in Ghana Edward Brenya 1* Samuel Adu-Gyamfi 2 1. History and Political Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, PMB, Kumasi Ashanti, Ghana 2. History and Political Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, PMB, Kumasi Ashanti, Ghana *Email of corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The provision of healthcare in Ghana from the pre-colonial period to the 4 th Republic has been characterized by struggles to maintain dominance. While the politics in the pre-independence period focused on the manner of providing healthcare, the post-independence period encapsulates healthcare financing. Using the interest groups theory, the study examines the manner and motive of healthcare management in Ghana. The study finds that a coalition of healthcare interest groups often comprising healthcare providers, government functionaries, bureaucrats, and the World Bank and IMF etc., (from the 1970s), uses the definition of healthcare management to maintain leverage in the management of healthcare. Healthcare management in the pre-colonial period was defined as interventionism while the colonial administration focused on scientific therapy. The post-colonial period witnessed a shift of focus to healthcare financing and Nkrumah’ government adopted free healthcare system financed by the state. The Busia’s government focused on sustainability based on payment of small user fee. -

Misconceptions, Misinformation and Politics of COVID-19 on Social Media: a Multi-Level Analysis in Ghana

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 05 May 2021 doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.613794 Misconceptions, Misinformation and Politics of COVID-19 on Social Media: A Multi-Level Analysis in Ghana Philip Teg-Nefaah Tabong 1* and Martin Segtub 2 1 Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences, School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana Legon, Accra, Ghana, 2 Department of Communication Studies, University of Professional Studies, Accra, Ghana Background: Ghana developed an Emergency Preparedness and Response Plan (EPRP) in response to the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS CoV-2) pandemic. A key strategy in the EPRP is to mobilize national resources and put in place strategies for improved risk and behavioral change communication. Nonetheless, concerns have been raised on social media about COVID-19 misinformation and misconceptions. This study used social media content to determine the types, forms and the effects of the myths, misconceptions and misinformation in Ghana’s COVID-19 containment. Method: The study was conducted in three phases involving the use of both primary and secondary data. Review of social media information on COVID-19 was done. This was complemented with document review and interviews with key stakeholders with expertise in the management of public health emergencies and mass communication Edited by: experts (N = 18). All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using NVivo 12. Fredrick Ogenga, Rongo University, Kenya Results: The study showed a changing pattern in the misconceptions and Reviewed by: misinformation about COVID-19. Initially myths were largely on causes and vulnerability. Rasha El-Ibiary, It was widely speculated that black people had some immunity against COVID-19. -

State of the Nation's Health Report

STATE OF THE NATION’S HEALTH REPORT December 2018 University of Ghana, School of Public Health sstate_of_the_nations_interior_new.inddtate_of_the_nations_interior_new.indd 1 005/02/195/02/19 111.061.06 Contributors to the Report This report was authored by the following persons: Chapter 1: Overview Dr. Justice Nonvignon, University of Ghana School of Public Health Dr. Richmond Aryeetey, University of Ghana School of Public Health Chapter 2: Health Service Delivery and Outcome Dr. George Amofah, Ghana Health Service Dr. Mawuli Dzodzomenyo, University of Ghana School of Public Health Dr. Reginald Quansah, University of Ghana School of Public Health Professor Augustine Ankomah, University of Ghana School of Public Health Chapter 3: Financing the Health Sector Dr. Genevieve C. Aryeetey, University of Ghana School of Public Health Professor Moses Aikins, University of Ghana School of Public Health Chapter 4: Human Resources for Health Dr. Abu Manu, University of Ghana School of Public Health Dr. Ernest Tei Maya, University of Ghana School of Public Health Dr. Adolphina Addo-Lartey, University of Ghana School of Public Health Dr. Aaron Abuosi, University of Ghana Business School Chapter 5: Health Commodities and Technology Dr. Kwabena Frimpong-Manso Opuni, University of Ghana School of Pharmacy Dr. Amos Laar, University of Ghana School of Public Health Dr. Kojo Arhinful, Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research Chapter 6: Health Management Information System Dr. Patricia Akweongo, University of Ghana School of Public Health Dr. Bismark Sarfo, University of Ghana School of Public Health Chapter 7: Leadership and Governance Dr. Abdallah Ibrahim, University of Ghana School of Public Health Dr. Emmanuel Asampong, University of Ghana School of Public Health Dr. -

Ghana, Lesotho, and South Africa: Regional Expansion of Water Supply in Rural Areas

Ghana, Lesotho, and South Africa: Regional Expansion of Water Supply in Rural Areas Water, sanitation, and hygiene are essential for achieving all the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and hence for contributing to poverty eradication globally. This case study contributes to the learning process on scaling up poverty reduction by describing and analyzing three programs in rural water and sanitation in Africa: the national rural water sector reform in Ghana, the national water and sanitation program in South Africa, and the national sanitation program in Lesotho. These national programs have made significant progress towards poverty elimination through improved water and sanitation. Although they are all different, there are several general conclusions that can validly be drawn from them: · Top-level political commitment to water and sanitation, sustained consistently over a long time period, is critically important to the success of national sector programs. · Clear legislation is necessary to give guidance and confidence to all the agencies working in the sector. · Devolution of authority from national to local government and communities improves the accountability of water and sanitation programs. · The involvement of a wide range of local institutions—social, economic, civil society, and media — empowers communities and stimulates development at the local scale. · The sensitive, flexible, and country-specific support of external agencies can add significant momentum to progress in the water and sanitation sector. Background and context Over the past decade, the rural water and sanitation sector in Ghana has been transformed from a centralized supply-driven model to a system in which local government and communities plan together, communities operate and maintain their own water services, and the private sector is active in providing goods and services. -

The Changing Face of Money: Preferences for Different Payment Forms in Ghana and Zambia

The Changing Face of Money: Preferences for Different Payment Forms in Ghana and Zambia Vivian A. Dzokoto Virginia Commonwealth University Elizabeth N. Appiah Pentecost University College Laura Peters Chitwood Counseling & Advocacy Associates Mwiya L. Imasiku University of Zambia Mobile Money (MM) is now a popular medium of exchange and store of value in parts of Africa, Latin America and Asia. As payment modalities emerge, consumer preferences for different payment tools evolve. Our study examines the preference for, and use of MM and other payment forms in both Ghana and Zambia. Our multi-method investigation indicates that while MM preference and awareness is high, scope of use is low in Ghana and Zambia. Cash remains the predominant mode of business transaction in both countries. Increased merchant acceptability is needed to improve the MM ecology in these countries. 1. INTRODUCTION The materiality of money has evolved over time, evidenced by the emergence of debit and credit cards in the twentieth century (Borzekowski and Kiser, 2008; Schuh and Stavins, 2010). Currently, mobile forms of payment are reaching widespread use in many regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, which is the fastest growing market for mobile phones worldwide (International Telecommunication Union [ITU], 2009). For example, M-Pesa is an extremely popular form of mobile payment in Kenya, possibly due to structural and cultural factors (Omwansa and Sullivan, 2012). However, no major form of money from the twentieth century has been completely phased out, as people exercise preferences for which form of money to use. Based on the evolution of payment methods, the current study explores perceptions and utilization of Mobile Money (MM) in Ghana, West Africa and in Zambia, South-Central Africa. -

New Evidence on ADOLESCENT SEXUAL and REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH NEEDS

Protecting the Next Generation in Ghana NEW EVIDENCE ON ADOLESCENT SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH NEEDS Protecting the Next Generation in Ghana: New Evidence on Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs Laura Hessburg Kofi Awusabo-Asare Akwasi Kumi-Kyereme Joana O. Nerquaye-Tetteh Francis Yankey Ann Biddlecom Melanie Croce-Galis Acknowledgments The authors thank the following colleagues for their com- de la Population (Burkina Faso); Kofi Awusabo-Asare and ments and help in developing this report: Akinrinola Akwasi Kumi-Kyereme, University of Cape Coast (Ghana); Bankole, Leila Darabi, Ann Moore, Jennifer Nadeau, Kate Alister Munthali and Sidon Konyani, Centre for Social Patterson and Susheela Singh, all currently or formerly of Research (Malawi); Stella Neema and Richard Kibombo, the Guttmacher Institute; Victoria Ebin, independent con- Makerere Institute of Social Research (Uganda); Eliya sultant; Augustine Tanle, University of Cape Coast; and Zulu, Nyovani Madise and Alex Ezeh, African Population Adjoa Nyanteng Yenyi, Planned Parenthood Association of and Health Research Center (Kenya); and Akinrinola Ghana. The report was edited by Peter Doskoch; Kathleen Bankole, Ann Biddlecom, Ann Moore and Susheela Singh Randall coordinated the layout and printing. of the Guttmacher Institute. Valuable guidance was pro- vided by Patricia Donovan, Melanie Croce-Galis and Leila The report greatly benefited from the careful reading and Darabi of the Guttmacher Institute. For implementation of feedback given by the following external peer reviewers: the national surveys of adolescents, the authors gratefully George Amofah, Ghana Health Service; Esther Apewokin, acknowledge the work of their colleagues at ORC Macro— National Population Council; A. F. Aryee, University of specifically, Pav Govindasamy, Albert Themme, Jeanne Ghana; Lord Dartey, Joint United Nations Programme Cushing, Alfredo Aliaga and Rebecca Stallings.