Implementation of Knowledge Management: a Comparative Study of the Secretariat of the House of Representatives and the Senate of the Thai Parliament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional & Parliamentary Information

UNION INTERPARLEMENTAIRE INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION CCoonnssttiittuuttiioonnaall && PPaarrlliiaammeennttaarryy IInnffoorrmmaattiioonn Half-yearly Review of the Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments Preparations in Parliament for Climate Change Conference 22 in Marrakech (Abdelouahed KHOUJA, Morocco) National Assembly organizations for legislative support and strengthening the expertise of their staff members (WOO Yoon-keun, Republic of Korea) The role of Parliamentary Committee on Government Assurances in making the executive accountable (Shumsher SHERIFF, India) The role of the House Steering Committee in managing the Order of Business in sittings of the Indonesian House of Representatives (Dr Winantuningtyastiti SWASANANY, Indonesia) Constitutional reform and Parliament in Algeria (Bachir SLIMANI, Algeria) The 2016 impeachment of the Brazilian President (Luiz Fernando BANDEIRA DE MELLO, Brazil) Supporting an inclusive Parliament (Eric JANSE, Canada) The role of Parliament in international negotiations (General debate) The Lok Sabha secretariat and its journey towards a paperless office (Anoop MISHRA, India) The experience of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies on Open Parliament (Antonio CARVALHO E SILVA NETO) Web TV – improving the score on Parliamentary transparency (José Manuel ARAÚJO, Portugal) Deepening democracy through public participation: an overview of the South African Parliament’s public participation model (Gengezi MGIDLANA, South Africa) The failed coup attempt in Turkey on 15 July 2016 (Mehmet Ali KUMBUZOGLU) -

Vision Statement from the National Anti-Corruption Strategy. “A Society

Vision statement from the National Anti-Corruption Strategy. “A society founded on discipline, integrity and ethics with all sectors participating in the prevention and suppression of corruption.” Notification to Members of the 'National Assembly of Thailand' Mr. Chakradharm Dharmasakti, M.D. Senator: Other Sectors The National Assembly of Thailand Building one Parliament House of Thailand Dusit, Bangkok, Thailand 10300. Dear Senator Dharmasakti, My name is Brian Barber I am an Australian married to a Thai National, my home is in the Provence of UdonThani. What I have uncovered is a system of endemic; community organised electoral corruption that stretches from the very bottom to the very top. In January of this year 2013 my stepson ran as a candidate for Mayor in the local elections of Ban That in the province of UdonThani, with my support. This support was meant to be 'above board' and follow the rules of democracy and decency as laid out on the Electoral Commission Thailand's web site for all to see and study. I have spent many years educating my stepson son to a high university level, all the time teaching him to appreciate and value the gift of living in a democracy and of his responsibilities to the democratic process. Please refer to document number - http://www.ecesolutions.info 1 - 'Politics is the art of persuasion' - 12th Feb 2012 (in Thai and English) 2 - 'This is our Platform' - 9th May 2012 (in Thai and English) 3 - 'The Pictorial Plan' (pdf English) 4 - 'Democratic process in local Mayoral election' - 30May 2012 (in Thai and English) To ECT Chairman Mr. -

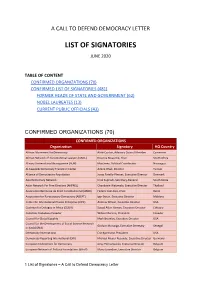

List of Signatories June 2020

A CALL TO DEFEND DEMOCRACY LETTER LIST OF SIGNATORIES JUNE 2020 TABLE OF CONTENT CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED LIST OF SIGNATORIES (481) FORMER HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT (62) NOBEL LAUREATES (13) CURRENT PUBLIC OFFICIALS (43) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS Organization Signatory HQ Country African Movement for Democracy Ateki Caxton, Advisory Council Member Cameroon African Network of Constitutional Lawyers (ANCL) Enyinna Nwauche, Chair South Africa Alinaza Universitaria Nicaraguense (AUN) Max Jerez, Political Coordinator Nicaragua Al-Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center Amine Ghali, Director Tunisia Alliance of Democracies Foundation Jonas Parello-Plesner, Executive Director Denmark Asia Democracy Network Ichal Supriadi, Secretary-General South Korea Asian Network For Free Elections (ANFREL) Chandanie Watawala, Executive Director Thailand Association Béninoise de Droit Constitutionnel (ABDC) Federic Joel Aivo, Chair Benin Association for Participatory Democracy (ADEPT) Igor Botan, Executive Director Moldova Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) Andrew Wilson, Executive Director USA Coalition for Dialogue in Africa (CODA) Souad Aden-Osman, Executive Director Ethiopia Colectivo Ciudadano Ecuador Wilson Moreno, President Ecuador Council for Global Equality Mark Bromley, Executive Director USA Council for the Development of Social Science Research Godwin Murunga, Executive Secretary Senegal in (CODESRIA) Democracy International Eric Bjornlund, President USA Democracy Reporting International -

The Politics of the Constitutional Amendment Regarding The

วารสารรัฐศาสตร์และรัฐประศาสนศาสตร์ ปีที่ 11 ฉบับที่ 2 (กรกฎาคม-ธันวาคม 2563): 219-252 When the Minority Overruled the Majority: The Politics of the Constitutional Amendment Regarding the Acquisition of Senators in Thailand in 20131 Purawich Watanasukh2 Received: April 17, 2019 Revised: June 30, 2019 Accepted: July 12, 2019 Abstract In 2013, the ruling Pheu Thai Party, backed by former premier Thaksin Shinawatra, proposed an amendment to the 2007 Constitution by making the Senate fully elected. Drafted after the 2006 coup, the 2007 Constitution created a senate that consists of half elected and half appointed senators. Controversially, the Constitutional Court ruled that this amendment was unconstitutional because it attempts to overthrow the democratic regime of government with the king as head of state. Why was this constitutional amendment unsuccessful? This paper argues that this amendment must be understood in terms of political struggle between the new elite rising from electoral politics (Thaksin Shinawatra and his party), which has majority of votes as its legitimacy, while the old elite (the military, bureaucracy) premises its legitimacy on traditional institutions and attempts to retain influence through unelected institutions. ค าส าคัญ Senate, Thailand, Constitution 1 This article is a part of the author’s PhD research titled “The Politics and Institutional Change in the Senate of Thailand”, funded by the University of Canterbury Doctoral Scholarship 2 Department of Political Science and International Relations, University of Canterbury, New Zealand. E-mail: [email protected] When the Minority Overruled the Majority • Purawich Watanasukh เมื่อเสียงข้างน้อยหักล้างเสียงข้างมาก: การเมืองของการแก้ไขรัฐธรรมนูญ ในประเด็นที่มาของสมาชิกวุฒิสภาในประเทศไทย พ.ศ. 2556 ปุรวิชญ์ วัฒนสุข3 บทคัดย่อ ในปี พ.ศ. 2556 รัฐบาลพรรคเพื่อไทยซึ่งได้รับการสนับสนุนจากทักษิณ ชินวัตร ได้เสนอญัตติให้มีการแก้ไขรัฐธรรมนูญ พ.ศ. -

Plenary Minutes Marrakech

MINUTES OF THE SPRING SESSION MARRAKECH 18-21 MARCH 2002 ASSOCIATION OF SECRETARIES GENERAL OF PARLIAMENTS Minutes of the Spring Session 2002 Marrakech 18-21 March 2002 LIST OF ATTENDANCE MEMBERS PRESENT Mr Artan Banushi Albania Dr Allauoa Layeb Algeria Mr Diogo De Jesus Angola Mr Valenti Marti Castanyer Andorra Mr Ian Harris Australia Mr Georg Posch Austria Mr Kazi Rakibuddin Ahmad Bangladesh Mr Dmitry Shilo Belarus Mr Robert Myttenaere Belgium Mr Georges Brion Belgium Mr Vedran Hadzovik Bosnia & Herzegovina Mr Ognyan Avramov Bulgaria Mr Prosper Vokouma Burkina Faso Mr Carlos Hoffmann Contreras Chile Mr Mateo Sorinas Balfego Council of Europe Mr Brissi Lucas Guehi Cote d’Ivoire Mr Constantinos Christoforou Cyprus Mr Peter Kynstetr Czech Republic Mr Paval Pelant Czech Republic Mr Bourhan Daoud Ahmed Djibouti Mr Farag El-Dory Egypt Mr Samy Mahran Egypt Mr Heike Sibul Estonia Mr Seppo Tiitinen Finland Mr Jean-Claude Becane France Mr Pierre Hontebeyrie France Mrs Hélène Ponceau France Mr Xavier Roques France Mrs Marie-Françoise Pucetti Gabon Mr Felix Owansango Daecken Gabon Mrs Siti Nurhajati Daud Indonesia Mr Arie Hahn Israel Mr Guiseppe Troccoli Italy 2 Mr Amuel Waweru Ndindiri Kenya Mr Sheridah Al-Mosharji Kuwait Mr H Morokole Lesotho Mr Pierre Dillenburg Luxembourg Mr Mamadou Santara Mali Mr Daadankhuu Batbaatar Mongolia Mr Mohamed Idrissi Kaitouni Morocco Mr Carlos Manuel Moxambique Mr Moses Ndjarakana Namibia Mrs Panuleni Shimutwikeni Namibia Mr Bas Nieuwenhuizen Netherlands Mrs Jacqueline Bisheuvel-Vermeijden Netherlands Mr Ibrahim -

ASGP Santiago Plenary Minutes

MINUTES OF THE SPRING SESSION SANTIAGO, CHILE 7 - 11 APRIL 2003 ASSOCIATION OF SECRETARIES GENERAL OF PARLIAMENTS Minutes of the Spring Session 2003 Santiago 7 - 11 April 2003 LIST OF ATTENDANCE MEMBERS PRESENT Mr Hafnaoui Amrani Algeria Mr Valenti Marti Castanyer Andorra Mr Ian Harris Australia Mr Kazi Rakibuddin Ahmad Bangladesh Mr Dmitry Shilo Belarus Mr Robert Myttenaere Belgium Mr Georges Brion Belgium Mr Ognyan Avramov Bulgaria Mr Prosper Vokouma Burkina Faso Mr Eutopio Lima Da Cruz Cape Verde Mr Carlos Hoffmann Contreras Chile Mr Carlos Loyola Opazo Chile Mr Brissi Lucas Guehi Cote d’Ivoire Mr Peter Kynstetr Czech Republic Mr Paval Pelant Czech Republic Mr Asnake Tadesse Ethiopia Mrs Mary Chapman Fiji Mr Jouri Vainio Finland Mr Jean-Claude Becane France Mrs Hélène Ponceau France Mr Xavier Roques France Mrs Marie-Françoise Pucetti Gabon Mr Dirk Brouer Germany Mr Kenneth E K Tachie Ghana Mr Mohamed Salifou Toure Guinea Mr Arteveld Pierre Jerome Haiti Mr Helgi Bernodusson Iceland Mrs Siti Nurhajati Daud Indonesia Mr Arie Hahn Israel Mr Guiseppe Troccoli Italy Dr Mohamad Al-Masalha Jordan Mr Zaid Zuraikat Jordan Mr Amuel Waweru Ndindiri Kenya Mr Mamadou Santara Mali Mr Namsraijav Luvsanjav Mongolia Mr Mohamed Idrissi Kaitouni Morocco Mr Moses Ndjarakana Namibia Mrs Panuleni Shimutwikeni Namibia Mr Bas Nieuwenhuizen Netherlands - 2 - Mrs Jacqueline Bisheuvel-Vermeijden Netherlands Mr Ibrahim Salim Nigeria Mr Hans Brattesta Norway Mr Vladimir Aksyonov Parliamentary Assembly of the Union of Belarus and the Russian Federation Mr Mahmood -

Message from the Chair Newsletter of the Ifla Section on Library and Research Services for Parliaments

NEWSLETTER OF THE IFLA SECTION ON LIBRARY A ND RESEARCH SERVICES FOR PARLIAMENTS J U L Y 2 0 1 6 MESSAGE FROM THE CHA IR INSIDE THIS ISSUE Dear Colleagues, Message from the Chair 1 Planning for the 32st Annual Pre-Conference of the IFLA Section on Library and Research Services How to join the Section 1 for Parliaments, hosted by the US Library of Congress, is going well. For the first time, the Section had to set a limit on the number of delegates, and we exceeded that number by the time registra- IFLAPARL Pre-conference 2 - 3 2016 tion ended in late April 2016. I wish to thank those who registered for your patience in working with the pre-conference staff to re-confirm your attendance so that we can accommodate those Share and connect 3 who were on the waiting list. At last count, we have confirmed delegates from 54 countries and 7 IFLA WLIC in Columbus, 4 - 5 parliamentary-related organizations. Delegates can expect a very interesting pre-conference pro- Ohio gramme. Recent events 6 - 7 The Section is partnering with the US House Democracy Partnership (HDP) and the National Dem- News from Parliamentary 8 ocratic Institute (NDI) to organize a two-day HDP Parliamentary Staff Institute with funding support Libraries & Research from the US Agency for International Development. Thirty-two delegates from Colombia, Georgia, Services Indonesia, Kenya, Kosovo, Liberia, Macedonia, Myanmar, Peru, Sri Lanka, Timor Leste, Tunisia and Ukraine were selected to participate in the Staff Institute on 8-9 August 2016 in the US Capi- tol. -

Senate and Politics of Thailand* 1Namphueng Puranasukhon, 2Supatra Amnuaysawasdi 3Thuwathida Suwannarat

Senate and Politics of Thailand* 1Namphueng Puranasukhon, 2Supatra Amnuaysawasdi 3Thuwathida Suwannarat 1Ramkhamhaeng University, Thailand. 2,3Suan Sunandha University, Thailand 1Email: [email protected] Received May 28, 2020; Revised June 10, 2020; Accepted July 20, 2020 Abstract This research is a documentary analysis of the current senator's duties that affect the changes in government formation of politics in Thailand, by using the form of synthesis and analysis of documents and related research both in Thailand and abroad. The objective is to study the functions of the senate and the politics of Thailand. The research found that the Senate in Thailand are both the elected and the appointed, which in the current state has seen changes in the Thai direction that are different from the past. With the additional authority to vote to support the Prime Minister, which may not be in alignment with the principle of duty in the way of practice in civilized world, the positive and negative impact for the Thai politics will still need the time to prove. Keywords: Authority; Politics of Thailand; Senate. Introduction The democratic regime, which is considered the power of government, comes from the people. With an important parliamentary organization that is a representative to act, which must be elected to be a representative of the people for the administration of the country in controlling, monitoring and supervising the administration of the government in accordance with the policy announced to the Council Thailand. The Thai parliament is developed from the Council of State or the Government Advisory Council, which has been in existence since the reign of King Rama V (Rama 5). -

Better Security Measures to Be Taken for Safety of SEA Games

THENew MOST RELIABLE NEWSPAPER LightAROUND YOU of Myanmar Volume XXI, Number 144 3rd Waxing of Tawthalin 1375 ME Saturday, 7 September, 2013 NAY PYI TAW, 7 Sept—U Thein Sein, President of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, has sent President U Thein Sein a message of felicitations to Her Excellency Ms Dilma Rousseff, President of the Federative Republic of Brazil, on the occasion of the Independence Day of the Federative Republic of Brazil which falls on felicitates Brazilian counterpart 7th September 2013.—MNA Better security measures to be taken for Republic of the Union of Myanmar President Office safety of SEA Games (Order No. 38/2013) nd NAY PYI TAW, 6 Sept— techniques for being able with the Olympic Charter committees, the remaining 2 Waxing of Tawthalin, 1375 ME The Leading Committee to successfully hold the and public participation in tasks and difficulties, (6 September, 2013) for Organizing the XXVII SEA Games, better security organizing the SEA Games. future tasks and matters SEA Games held the ninth measures for safety of the He urged the committees to to be coordinated with the Union Peace-making Work coordination meeting at the SEA Games, systematic strive for timely completion ministries concerned. Committee added with members hall of President Office, sports management, of preparatory tasks. Subcommittee chair- “The Union Peace-making Work Committee” here, this morning, with an presentation of entertain- Deputy Ministers for men Union Ministers, constituted under Order No. (15/2013) of the President address by Patron of the ment. He noted that the Sports U Thaung Htaik deputy ministers and Office dated 5 July 2013 has been added with the following Leading Committee Vice- work guidelines comprised and U Zaw Win reported officials presented reports persons as members. -

World E-Parliament Report 2010

United Nations Inter-Parliamentary Union World e-Parliament Report 2010 Prepared by the Global Centre for ICT in Parliament A partnership initiative of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and the Inter-Parliamentary Union inspired by the outcome of the World Summit on the Information Society United Nations Inter-Parliamentary Union World e-Parliament Report 2010 Prepared by the Global Centre for ICT in Parliament A partnership initiative of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and the Inter-Parliamentary Union inspired by the outcome of the World Summit on the Information Society Note The Global Centre for Information and Communication Technologies in Parliament is a joint partnership initiative of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and a group of national and regional parliaments launched in November 2005 on the occasion of the World Summit of the Information Society (WSIS) in Tunis. The Global Centre pursues two main objectives: a) strengthening the role of parliaments in the promotion of the Information Society, in light of the WSIS outcome, and b) promoting the use of ICT as a means to modernize parliamentary processes, increase transparency, accountability and participation, and improve inter-parliamentary cooperation. http://www.ictparliament.org The Global Centre for ICT in Parliament is administered by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Disclaimer This Report is a joint product of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and the Inter-Parliamentary Union through the Global Centre for ICT in Parliament. The views and opinions expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations and the Inter-Parliamentary Union. -

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

UNITED NATIONS TD Distr. United Nations GENERAL Conference TD/INF.37 on Trade and 25 May 2000 ENGLISH/FRENCH/SPANISH Development UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT CONFERENCE DES NATIONS UNIES SUR LE COMMERCE ET LEDEVELOPPEMENT CONFERENCIA DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS SOBRE COMERCIO Y DESARROLLO TENTH SESSION - DIXIÈME SESSION – DÉCIMO PERÍODO DE SESIONES LIST OF PARTICIPANTS LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS LISTA DE PARTICIPANTES Note: The format and data of the entries in this list are as provided to the secretariat GE. 00- TD/INF.37 Page 2 MEMBERS AFGHANISTAN S.E. M. Wahidullah SABAOUN, Ministre des Finances M. Mohammad NATEQUI, Ministre du Commerce M. Abdul Wahab HAIDAR, Chargé des Affaires économiques et commerciales M. Humayun TANDAR, Ministre Conseiller, Chargé d’Affaires à la Mission ALBANIA Mme Adriana CIVICI, Coordinatrice Générale au Secrétariat permanent, Coordination des relations avec l’OMC ALGERIA S.E. M. Abdelaziz BOUTEFLIKA, Président de la République Algérienne et Populaire S.E. Mourad MEDELCI, Ministre du Commerce M. Abdellatif RAHAL, Diplomat Conseiller à la Présidence de la Republique M. Mohamad BEN AMMAR ZARHOUNI, Conseiller à la Présidence de la Republique M. Hachemi DJIYAR, Conseiller à la Présidence de la Republique M. Abdel OUAHAB ELGRADECTI, Conseiller à la Présidence M. Ammar ABBA, Chef des Relations multilatérales, Ministère des Affaires S.E. M. Rachid BLADEHANE, Ambassadeur, Malaisie Mlle Farida AIOUAZE, Conseiller, Mission Permanente, Genève M. Mouloud HEDIR, Directeur Général du Commerce éxtérieur, Ministère du Commerce M. Abdelmalek ZOUBEIDI, Directeur des Statistiques M. Abdelrahmane HAMIDAOUI, Ministre plénipotentiaire Mlle Ferroukhi TAOUS, Chargée de mission à la Présidence ANGOLA Sr. Georges Rebelo PINTO CHICOTY, Viceministro des Relaciones Exteriores Sr. -

Newsletter # 4-2014NEW.Indd

1 ISSUE 4 (October-December 2014) RU President Congratulating RU Student on Receiving Royal Tertiary Awards Assistant Professor Wutisak Lapcharoensap, RU president, congratulated Miss Patchara Kaenpuang, a student at the Faculty of Law, Ramkhamhaeng University Regional Campus in Honor of His Majesty the King in Sukhothai. She received a Royal Tertiary Award, Bangkok Metropolis Area for the academic year 2013. Mr. Sommai Surachai, Vice-President for Students Affairs and Miss Khwanruen Pankaew, a recipient of the same award in 2012, participated in the proceedings on October 1st at Reception Room, 2nd floor, Academic Services and Administration Building, RU. Signing of an MOU Between RU and Goethe Institute, Thailand A ceremony for the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for academic cooperation between RU and Goethe Institute, Thailand was held on October 1st at 2 p.m. at the Meeting Room, 3rd floor, Academic Services and Administration Building. Assistant Professor Wutisak Lapcharoensap, RU president and Dr. Hans-Dieter Dräxler, Goethe Institute, Thailand Department of Western Languages, Faculty is the enhancement of research, management signed the said MOU. Dr. Johannes Goebert, of Humanities, and exchange students from of educational programs, training, the exchange director of Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst the Federal Republic of Germany witnessed the of faculty and students at both undergraduate (DAAD) Information Center in Thailand, RU ceremony. and graduate levels in the field of German administrators, the director of Institute of The objective of academic cooperation to the end of benefitting students, faculty, International Studies, RU, lecturers from the between RU and Goethe Institute, Thailand and the university as a whole.