Constitutional & Parliamentary Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A/HRC/38/25 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/38/25 General Assembly Distr.: General 17 May 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-eighth session 18 June–6 July 2018 Agenda items 2 and 5 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Human rights bodies and mechanisms Contribution of parliaments to the work of the Human Rights Council and its universal periodic review Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights* Summary The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 35/29, in which the Council requested the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to prepare a study, in close cooperation with the Inter-Parliamentary Union and in consultation with States, United Nations agencies and other relevant stakeholders, on how to promote and enhance synergies between parliaments and the work of the Human Rights Council and its universal periodic review, and to present it to the Council at its thirty-eighth session, in order to provide States and other relevant stakeholders with elements that could serve as orientation to strengthen their interaction towards the effective promotion and protection of human rights. The present report focuses on the role of parliaments in the field of human rights and contains an analysis of responses to a questionnaire for parliaments sent by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to Member States, United Nations agencies and other stakeholders through a note verbale dated 16 November 2017, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 35/29. -

Constitutional & Parliamentary Information

UNION INTERPARLEMENTAIRE INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION CCoonnssttiittuuttiioonnaall && PPaarrlliiaammeennttaarryy IInnffoorrmmaattiioonn Half-yearly Review of the Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments Preparations in Parliament for Climate Change Conference 22 in Marrakech (Abdelouahed KHOUJA, Morocco) National Assembly organizations for legislative support and strengthening the expertise of their staff members (WOO Yoon-keun, Republic of Korea) The role of Parliamentary Committee on Government Assurances in making the executive accountable (Shumsher SHERIFF, India) The role of the House Steering Committee in managing the Order of Business in sittings of the Indonesian House of Representatives (Dr Winantuningtyastiti SWASANANY, Indonesia) Constitutional reform and Parliament in Algeria (Bachir SLIMANI, Algeria) The 2016 impeachment of the Brazilian President (Luiz Fernando BANDEIRA DE MELLO, Brazil) Supporting an inclusive Parliament (Eric JANSE, Canada) The role of Parliament in international negotiations (General debate) The Lok Sabha secretariat and its journey towards a paperless office (Anoop MISHRA, India) The experience of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies on Open Parliament (Antonio CARVALHO E SILVA NETO) Web TV – improving the score on Parliamentary transparency (José Manuel ARAÚJO, Portugal) Deepening democracy through public participation: an overview of the South African Parliament’s public participation model (Gengezi MGIDLANA, South Africa) The failed coup attempt in Turkey on 15 July 2016 (Mehmet Ali KUMBUZOGLU) -

RIGHTS at RISK

RIGHTS at RISK Time for Action Observatory on the Universality of Rights Trends Report 2021 RIGHTS AT RISK: TIME FOR ACTION Observatory on the Universality of Rights Trends Report 2021 Chapter 4: Anti-Rights Actors 4 www.oursplatform.org 72 RIGHTS AT RISK: TIME FOR ACTION Observatory on the Universality of Rights Trends Report 2021 Chapter 4: Anti-Rights Actors Chapter 4: CitizenGo Anti-Rights Actors – Naureen Shameem AWID Mission and History ounded in August 2013 and headquartered Fin Spain,221 CitizenGo is an anti-rights platform active in multiple regions worldwide. It describes itself as a “community of active citizens who work together, using online petitions and action alerts as a resource, to defend and promote life, family and liberty.”222 It also claims that it works to ensure respect for “human dignity and individuals’ rights.”223 United Families Ordo Iuris, International Poland Center for World St. Basil the Istoki Great Family and Endowment Congress of Charitable Fund, Russia Foundation, Human Rights Families Russia (C-Fam) The International Youth Alliance Coalition Russian Defending Orthodox Freedom Church Anti-Rights (ADF) Human Life Actors Across International Heritage Foundation, USA FamilyPolicy, Russia the Globe Group of Friends of the and their vast web Family of connections Organization Family Watch of Islamic International Cooperation Anti-rights actors engage in tactical (OIC) alliance building across lines of nationality, religion, and issue, creating a transnational network of state and non-state actors undermining rights related to gender and sexuality. This El Yunque, Mexico visual represents only a small portion Vox party, The Vatican World Youth Spain of the global anti-rights lobby. -

Theparliamentarian

TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2015 | Issue Three XCVI | Price £13 Elections and Voting Reform PLUS Commonwealth Combatting Looking ahead to Millenium Development Electoral Networks by Terrorism in Nigeria CHOGM 2015 in Malta Goals Update: The fight the Commonwealth against TB Secretary-General PAGE 150 PAGE 200 PAGE 204 PAGE 206 The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) Shop CPA business card holders CPA ties CPA souvenirs are available for sale to Members and officials of CPA cufflinks Commonwealth Parliaments and Legislatures by CPA silver-plated contacting the photoframe CPA Secretariat by email: [email protected] or by post: CPA Secretariat, Suite 700, 7 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA, United Kingdom. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of good governance and implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. Calendar of Forthcoming Events Confirmed at 24 August 2015 2015 September 2-5 September CPA and State University of New York (SUNY) Workshop for Constituency Development Funds – London, UK 9-12 September Asia Regional Association of Public Accounts Committees (ARAPAC) Annual Meeting - Kathmandu, Nepal 14-16 September Annual Forum of the CTO/ICTs and The Parliamentarian - Nairobi, Kenya 28 Sept to 3 October West Africa Association of Public Accounts Committees (WAAPAC) Annual Meeting and Community of Clerks Training - Lomé, Togo 30 Sept to 5 October CPA International -

Examining Communication Techniques Adopted by the Senate to Promote Mandatory Public Participation in Kenya

EXAMINING COMMUNICATION TECHNIQUES ADOPTED BY THE SENATE TO PROMOTE MANDATORY PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN KENYA BY ADHIAMBO LIDYA CONCEPTA A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI, SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN COMMUNICATION STUDIES 2018 i DECLARATION This is to certify that this research is my own original work and is in no way a reproduction of any other work that has been previously presented for award of a degree in any University. No part of this project may be reproduced without the prior permission of the author or the University of Nairobi. Adhiambo Lidya Concepta ……………………. ………………….. K50/81032/2012 Signature Date This research has been submitted for examination with my approval as University Supervisor. Dr. Peter Onyango Onyoyo ……………………. ………………….. Signature Date ii DEDICATION To my dad, the late James Owino Agiso Abonyo, who encouraged me to further my studies and my mother, Monica Akumu Obul-Owino, for teaching me the values of education. I would also like to dedicate this project to my husband, James Otieno Kaoga and my sons; Sammy Kaoga, Paul Kaoga and Austin Kaoga for their patience through this whole project. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I give thanks to the Almighty God for the gift of life and His providence. He has been my guide in the entire study. I would also like to appreciate Dr. Peter Onyango Onyoyo of the University Of Nairobi School Of Law. As my supervisor, he provided insights and helped me explore new ideas during my study. My appreciation also goes to the faculty members, School of Journalism, the University of Nairobi. -

Friday, 22Nd May, 2020

May 22, 2020 SENATE DEBATES 1 PARLIAMENT OF KENYA THE SENATE THE HANSARD Friday, 22nd May, 2020 Special Sitting (Convened via Kenya Gazette Notice No.3649 of 20th May, 2020) The House met at the Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings, at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Lusaka) in the Chair] PRAYER COMMUNICATION FROM THE CHAIR CONVENING OF SPECIAL SITTING TO CONSIDER MOTION ON PROPOSED REMOVAL OF SEN. (PROF.) KINDIKI FROM OFFICE OF DEPUTY SPEAKER, SENATE The Speaker (Hon. Lusaka): Hon. Senators, you will recall that during the Afternoon Sitting of the Senate held on Tuesday, 19th May 2020, the Senate Majority Whip, Sen. Irungu Kang’ata, MP, gave a Notice of Motion for the removal of Sen. (Prof.) Kithure Kindiki, MP, from the Office of the Deputy Speaker of the Senate. Subsequently, by a letter dated 19th May 2020, the Senate Majority Leader requested the Speaker to convene a Special Sitting of the Senate pursuant to Standing Order 30(1), to consider the Motion filed by the Senate Majority Whip for the removal of Sen. (Prof.) Kithure Kindiki, MP, from the Office of the Deputy Speaker of the Senate. The request by the Senate Majority Leader, was supported by the requisite number of Senators (15 Senators) as required by Standing Order 30 (1). Hon. Senators, following consideration of the request by the Senate Majority Leader, I was satisfied that the request met the requirements of Standing Order 30 (2). Accordingly, and pursuant to Standing Order 30 (3), I issued a Gazette Notice No.3649 of 20th May 2020 in respect of this Special Sitting, which was circulated to all Hon. -

Vision Statement from the National Anti-Corruption Strategy. “A Society

Vision statement from the National Anti-Corruption Strategy. “A society founded on discipline, integrity and ethics with all sectors participating in the prevention and suppression of corruption.” Notification to Members of the 'National Assembly of Thailand' Mr. Chakradharm Dharmasakti, M.D. Senator: Other Sectors The National Assembly of Thailand Building one Parliament House of Thailand Dusit, Bangkok, Thailand 10300. Dear Senator Dharmasakti, My name is Brian Barber I am an Australian married to a Thai National, my home is in the Provence of UdonThani. What I have uncovered is a system of endemic; community organised electoral corruption that stretches from the very bottom to the very top. In January of this year 2013 my stepson ran as a candidate for Mayor in the local elections of Ban That in the province of UdonThani, with my support. This support was meant to be 'above board' and follow the rules of democracy and decency as laid out on the Electoral Commission Thailand's web site for all to see and study. I have spent many years educating my stepson son to a high university level, all the time teaching him to appreciate and value the gift of living in a democracy and of his responsibilities to the democratic process. Please refer to document number - http://www.ecesolutions.info 1 - 'Politics is the art of persuasion' - 12th Feb 2012 (in Thai and English) 2 - 'This is our Platform' - 9th May 2012 (in Thai and English) 3 - 'The Pictorial Plan' (pdf English) 4 - 'Democratic process in local Mayoral election' - 30May 2012 (in Thai and English) To ECT Chairman Mr. -

Inter-Parliamentary Union

Const. Parl. Inf. 64th year (2014), n°208 INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION Aims The Inter-Parliamentary Union, whose international Statute is outlined in a Headquarters Agreement drawn up with the Swiss federal authorities, is the only world-wide organisation of Parliaments. The aim of the Inter-Parliamentary Union is to promote personal contacts between members of all Parliaments and to unite them in common action to secure and maintain the full participation of their respective States in the firm establishment and development of representative institutions and in the advancement of the work of international peace and cooperation, particularly by supporting the objectives of the United Nations. In pursuance of this objective, the Union makes known its views on all international problems suitable for settlement by parliamentary action and puts forward suggestions for the development of parliamentary assemblies so as to improve the working of those institutions and increase their prestige. Membership of the Union Please refer to IPU site (http://www.ipu.org). Structure The organs of the Union are: 1. The Inter-Parliamentary Conference, which meets twice a year; 2. The Inter-Parliamentary Council, composed of two members of each affiliated Group; 3. The Executive Committee, composed of twelve members elected by the Conference, as well as of the Council President acting as ex officio President; 4. Secretariat of the Union, which is the international secretariat of the Organisation, the headquarters being located at: Inter-Parliamentary Union 5, chemin du Pommier Case postale 330 CH-1218 Le Grand Saconnex Genève (Suisse) Official Publication The Union’s official organ is the Inter-Parliamentary Bulletin, which appears quarterly in both English and French. -

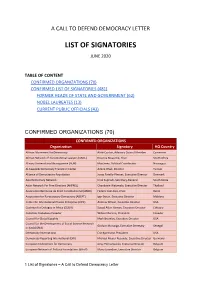

List of Signatories June 2020

A CALL TO DEFEND DEMOCRACY LETTER LIST OF SIGNATORIES JUNE 2020 TABLE OF CONTENT CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED LIST OF SIGNATORIES (481) FORMER HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT (62) NOBEL LAUREATES (13) CURRENT PUBLIC OFFICIALS (43) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS Organization Signatory HQ Country African Movement for Democracy Ateki Caxton, Advisory Council Member Cameroon African Network of Constitutional Lawyers (ANCL) Enyinna Nwauche, Chair South Africa Alinaza Universitaria Nicaraguense (AUN) Max Jerez, Political Coordinator Nicaragua Al-Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center Amine Ghali, Director Tunisia Alliance of Democracies Foundation Jonas Parello-Plesner, Executive Director Denmark Asia Democracy Network Ichal Supriadi, Secretary-General South Korea Asian Network For Free Elections (ANFREL) Chandanie Watawala, Executive Director Thailand Association Béninoise de Droit Constitutionnel (ABDC) Federic Joel Aivo, Chair Benin Association for Participatory Democracy (ADEPT) Igor Botan, Executive Director Moldova Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) Andrew Wilson, Executive Director USA Coalition for Dialogue in Africa (CODA) Souad Aden-Osman, Executive Director Ethiopia Colectivo Ciudadano Ecuador Wilson Moreno, President Ecuador Council for Global Equality Mark Bromley, Executive Director USA Council for the Development of Social Science Research Godwin Murunga, Executive Secretary Senegal in (CODESRIA) Democracy International Eric Bjornlund, President USA Democracy Reporting International -

Theparliamentarian

100 years of publishing 1920-2020 TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2020 | Volume 101 | Issue Four | Price £14 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOCIAL MEDIA AND PARLIAMENTARY DEMOCRACY IN THE COMMONWEALTH PAGES 308-323 PLUS The City of London, its Hansard Technology: Parliamentary Why Women’s Remembrancer and All Change for the Expressions & Leadership Matters the Commonwealth Official Report Practices in the During COVID-19 and Commonwealth Beyond PAGE 334 PAGE 338 PAGE 340 PAGE 350 IN TIMES LIKE THESE PARLIAMENTS NEED ALL THE RESOURCES THEY CAN GET! DOWNLOAD CPA’S NEW PUBLICATION NOW www.cpahq.org/cpahq/modellaw THE CPA MODEL LAW FOR INDEPENDENT PARLIAMENTS Based on the important values laid down in the Commonwealth Latimer House Principles and the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers, the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) has created a MODEL LAW FOR INDEPENDENT PARLIAMENTS. This draft legislation is aimed at Commonwealth Parliaments to use as a template to create financially and administratively independent institutions. Specifically, the Model Law enables Parliaments to create Parliamentary Service Commissions and to ensure Parliaments across the Commonwealth have the resources they need to function effectively without the risk of Executive interference. www.cpahq.org STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of good governance, and implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. Calendar of Forthcoming Events Updated as at 16 November 2020 Please note that due to the COVID-19 (Coronavirus) global pandemic, many CPA events, conferences and activities have been postponed or cancelled. -

Parliament of Kenya the Senate

November 23, 2016 SENATE DEBATES 1 PARLIAMENT OF KENYA THE SENATE THE HANSARD Wednesday, 23rd November, 2016 The House met at the Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings, at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro) in the Chair] PRAYER COMMUNICATION FROM THE CHAIR SUMMIT ON PEACEFUL ELECTIONS, NATIONAL COHESION AND UNITY FOR SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro): Order, Senators. I have a Communication to make on the Summit for Peaceful Elections, National Cohesion and Unity for Socio-Economic Development. I wish to inform you that the Kenya Private Sector Alliance (KEPSA) has organized and invited all Senators to a leaders’ summit on peaceful elections, national cohesion for socio-economic development. KEPSA’s key focus areas are:- (i) Conducting high level advocacy on cost-cutting law and policy-related issues and ensuring Kenya is globally competitive while doing business. (ii) Coordinating the private sector in Kenya through various mechanisms and engagement advocacy that promotes economic growth. (iii) Developing and building capacity of Business Membership Organizations (BMOs) to strengthen, grow and represent their sectors adequately. It is in line with these areas that KEPSA has organized the leadership summit which will bring together all national leaders including all parliamentarians of both Houses. The summit is scheduled to take place from 2nd to 3rd December, 2016, at Leisure Lodge Resort in Mombasa County. Senators should depart for Mombasa on the evening of Thursday, 1st December, 2016. This is, therefore, to invite all of you to this very important meeting and to urge you to attend and participate effectively. You are requested to forward your preferred travel times to the office of the Clerk of the Senate for planning purposes. -

The Politics of the Constitutional Amendment Regarding The

วารสารรัฐศาสตร์และรัฐประศาสนศาสตร์ ปีที่ 11 ฉบับที่ 2 (กรกฎาคม-ธันวาคม 2563): 219-252 When the Minority Overruled the Majority: The Politics of the Constitutional Amendment Regarding the Acquisition of Senators in Thailand in 20131 Purawich Watanasukh2 Received: April 17, 2019 Revised: June 30, 2019 Accepted: July 12, 2019 Abstract In 2013, the ruling Pheu Thai Party, backed by former premier Thaksin Shinawatra, proposed an amendment to the 2007 Constitution by making the Senate fully elected. Drafted after the 2006 coup, the 2007 Constitution created a senate that consists of half elected and half appointed senators. Controversially, the Constitutional Court ruled that this amendment was unconstitutional because it attempts to overthrow the democratic regime of government with the king as head of state. Why was this constitutional amendment unsuccessful? This paper argues that this amendment must be understood in terms of political struggle between the new elite rising from electoral politics (Thaksin Shinawatra and his party), which has majority of votes as its legitimacy, while the old elite (the military, bureaucracy) premises its legitimacy on traditional institutions and attempts to retain influence through unelected institutions. ค าส าคัญ Senate, Thailand, Constitution 1 This article is a part of the author’s PhD research titled “The Politics and Institutional Change in the Senate of Thailand”, funded by the University of Canterbury Doctoral Scholarship 2 Department of Political Science and International Relations, University of Canterbury, New Zealand. E-mail: [email protected] When the Minority Overruled the Majority • Purawich Watanasukh เมื่อเสียงข้างน้อยหักล้างเสียงข้างมาก: การเมืองของการแก้ไขรัฐธรรมนูญ ในประเด็นที่มาของสมาชิกวุฒิสภาในประเทศไทย พ.ศ. 2556 ปุรวิชญ์ วัฒนสุข3 บทคัดย่อ ในปี พ.ศ. 2556 รัฐบาลพรรคเพื่อไทยซึ่งได้รับการสนับสนุนจากทักษิณ ชินวัตร ได้เสนอญัตติให้มีการแก้ไขรัฐธรรมนูญ พ.ศ.