The Politics of the Constitutional Amendment Regarding The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional & Parliamentary Information

UNION INTERPARLEMENTAIRE INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION CCoonnssttiittuuttiioonnaall && PPaarrlliiaammeennttaarryy IInnffoorrmmaattiioonn Half-yearly Review of the Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments Preparations in Parliament for Climate Change Conference 22 in Marrakech (Abdelouahed KHOUJA, Morocco) National Assembly organizations for legislative support and strengthening the expertise of their staff members (WOO Yoon-keun, Republic of Korea) The role of Parliamentary Committee on Government Assurances in making the executive accountable (Shumsher SHERIFF, India) The role of the House Steering Committee in managing the Order of Business in sittings of the Indonesian House of Representatives (Dr Winantuningtyastiti SWASANANY, Indonesia) Constitutional reform and Parliament in Algeria (Bachir SLIMANI, Algeria) The 2016 impeachment of the Brazilian President (Luiz Fernando BANDEIRA DE MELLO, Brazil) Supporting an inclusive Parliament (Eric JANSE, Canada) The role of Parliament in international negotiations (General debate) The Lok Sabha secretariat and its journey towards a paperless office (Anoop MISHRA, India) The experience of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies on Open Parliament (Antonio CARVALHO E SILVA NETO) Web TV – improving the score on Parliamentary transparency (José Manuel ARAÚJO, Portugal) Deepening democracy through public participation: an overview of the South African Parliament’s public participation model (Gengezi MGIDLANA, South Africa) The failed coup attempt in Turkey on 15 July 2016 (Mehmet Ali KUMBUZOGLU) -

Policy Statement of the Council of Ministers

Policy Statement of the Council of Ministers Delivered by Prime Minister Somchai Wongsawat to the National Assembly on Tuesday 7 October B.E. 2551 (2008) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Announcement on the Appointment i of the Prime Minister Announcement on the Appointment of Ministers ii Policy Statement of the Government of 1 Mr. Somchai Wongsawat, Prime Minister, to the National Assembly 1. Urgent policies to be implemented within the first year 3 2. National Security Policy 7 3. Social and Quality of Life Policy 8 4. Economic Policy 13 5. Policy on Land, Natural Resources, and the Environment 20 6. Policy on Science, Technology, Research and Innovation 22 7. Foreign Policy and International Economic Policy 23 8. Policy on Good Management and Governance 24 Annex A 29 Section 1 Enactment or revision of laws according to the provisions 29 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand Section 2 Draft laws that the Council of Ministers deems necessary 31 for the administration of state affairs, pursuant to Section 145 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand Annex B 33 List of the Cabinet’s Policy Topics in the Administration of State Affairs Compared with the Directive Principles of Fundamental State Policies in Chapter 5 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand 2 Announcement on the Appointment of the Prime Minister Bhumibol Adulyadej, Rex Phrabat Somdet Phra Paramintharamaha Bhumibol Adulyadej has graciously given a Royal Command for the announcement to be made that: Given the termination of the ministership of Mr. Samak Sundaravej, Prime Minister, under Section 182 paragraph 1 (7) of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, and the Speaker of the House of Representatives having humbly informed His Majesty that the House of Representatives has passed a resolution on 17 September B.E. -

Yingluck Takes Command 9 Aug 2011 at 07:50

Yingluck takes command 9 Aug 2011 at 07:50 With her husband and young son looking on, new prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra pledged allegiance to the monarchy and her full commitment towards working in the best interests of the country. Thailand’s first female prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra pays respects to a portrait of His Majesty the King as she receives the royal command appointing her as premier at PheuThai Party headquarters in Bangkok yesterday. MsYingluck is the country’s 28th prime minister. MEDIAPOOL Note: You have probably heard or read prime minister Yingluck's speech yesterday. The story below gives a good English-language summary. You might also be interested in our new facebook page at: http://www.facebook.com/bangkokpostlearning Click button to listen to Yingluck speaks and rightclick to download King endorses Yingluck as PM National reconciliation tops new govt's agenda Aekarach Sattaburuth His Majesty the King yesterday endorsed Yingluck Shinawatra as the country's first female prime minister. In her first address to the nation after receiving the royal command formalising her premiership, Ms Yingluck vowed her allegiance to the monarchy and pledged to foster national reconciliation. Her cabinet line-up is expected to be submitted for royal endorsement today. At 6.40pm yesterday, the secretary-general of the House of Representatives Pitoon Pumhiran brought the royal command to the Pheu Thai Party headquarters in Bangkok. Mr Pitoon read out the royal command appointing Ms Yingluck as the country's new premier after she was nominated for the top job uncontested on Friday by the majority of members of the House of Representatives. -

Vision Statement from the National Anti-Corruption Strategy. “A Society

Vision statement from the National Anti-Corruption Strategy. “A society founded on discipline, integrity and ethics with all sectors participating in the prevention and suppression of corruption.” Notification to Members of the 'National Assembly of Thailand' Mr. Chakradharm Dharmasakti, M.D. Senator: Other Sectors The National Assembly of Thailand Building one Parliament House of Thailand Dusit, Bangkok, Thailand 10300. Dear Senator Dharmasakti, My name is Brian Barber I am an Australian married to a Thai National, my home is in the Provence of UdonThani. What I have uncovered is a system of endemic; community organised electoral corruption that stretches from the very bottom to the very top. In January of this year 2013 my stepson ran as a candidate for Mayor in the local elections of Ban That in the province of UdonThani, with my support. This support was meant to be 'above board' and follow the rules of democracy and decency as laid out on the Electoral Commission Thailand's web site for all to see and study. I have spent many years educating my stepson son to a high university level, all the time teaching him to appreciate and value the gift of living in a democracy and of his responsibilities to the democratic process. Please refer to document number - http://www.ecesolutions.info 1 - 'Politics is the art of persuasion' - 12th Feb 2012 (in Thai and English) 2 - 'This is our Platform' - 9th May 2012 (in Thai and English) 3 - 'The Pictorial Plan' (pdf English) 4 - 'Democratic process in local Mayoral election' - 30May 2012 (in Thai and English) To ECT Chairman Mr. -

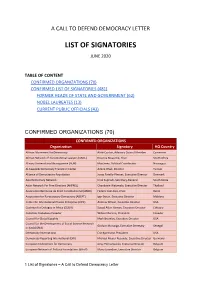

List of Signatories June 2020

A CALL TO DEFEND DEMOCRACY LETTER LIST OF SIGNATORIES JUNE 2020 TABLE OF CONTENT CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED LIST OF SIGNATORIES (481) FORMER HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT (62) NOBEL LAUREATES (13) CURRENT PUBLIC OFFICIALS (43) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS Organization Signatory HQ Country African Movement for Democracy Ateki Caxton, Advisory Council Member Cameroon African Network of Constitutional Lawyers (ANCL) Enyinna Nwauche, Chair South Africa Alinaza Universitaria Nicaraguense (AUN) Max Jerez, Political Coordinator Nicaragua Al-Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center Amine Ghali, Director Tunisia Alliance of Democracies Foundation Jonas Parello-Plesner, Executive Director Denmark Asia Democracy Network Ichal Supriadi, Secretary-General South Korea Asian Network For Free Elections (ANFREL) Chandanie Watawala, Executive Director Thailand Association Béninoise de Droit Constitutionnel (ABDC) Federic Joel Aivo, Chair Benin Association for Participatory Democracy (ADEPT) Igor Botan, Executive Director Moldova Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) Andrew Wilson, Executive Director USA Coalition for Dialogue in Africa (CODA) Souad Aden-Osman, Executive Director Ethiopia Colectivo Ciudadano Ecuador Wilson Moreno, President Ecuador Council for Global Equality Mark Bromley, Executive Director USA Council for the Development of Social Science Research Godwin Murunga, Executive Secretary Senegal in (CODESRIA) Democracy International Eric Bjornlund, President USA Democracy Reporting International -

Volume 16 AJHR 50 Parliament.Pdf

APPENDIX TO THE JOURNALS OF THE House of Representatives OF NEW ZEALAND 2011–2014 VOL. 16 J—PAPERS RELATING TO THE BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE IN THE REIGN OF HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH THE SECOND Being the Fiftieth Parliament of New Zealand 0110–3407 WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND: Published under the authority of the House of Representatives—2015 ARRANGEMENT OF THE PAPERS _______________ I—Reports and proceedings of select committees VOL. 1 Reports of the Education and Science Committee Reports of the Finance and Expenditure Committee Reports of the Government Administration Committee VOL. 2 Reports of the Health Committee Report of the Justice and Electoral Committee Reports of the Māori Affairs Committee Reports of the Social Services Committee Reports of the Officers of Parliament Committee Reports of the Regulations Review Committee VOL. 3 Reports of the Regulations Review Committee Reports of the Privileges Committee Report of the Standing Orders Committee VOL. 4 Reports of select committees on the 2012/13 Estimates VOL. 5 Reports of select committees on the 2013/14 Estimates VOL. 6 Reports of select committees on the 2014/15 Estimates Reports of select committees on the 2010/11 financial reviews of Government departments, Offices of Parliament, and reports on non-departmental appropriations VOL. 7 Reports of select committees on the 2011/12 financial reviews of Government departments, Offices of Parliament, and reports on non-departmental appropriations Reports of select committees on the 2012/13 financial reviews of Government departments, Offices of Parliament, and reports on non-departmental appropriations VOL. 8 Reports of select committees on the 2010/11 financial reviews of Crown entities, public organisations, and State enterprises VOL. -

Plenary Minutes Marrakech

MINUTES OF THE SPRING SESSION MARRAKECH 18-21 MARCH 2002 ASSOCIATION OF SECRETARIES GENERAL OF PARLIAMENTS Minutes of the Spring Session 2002 Marrakech 18-21 March 2002 LIST OF ATTENDANCE MEMBERS PRESENT Mr Artan Banushi Albania Dr Allauoa Layeb Algeria Mr Diogo De Jesus Angola Mr Valenti Marti Castanyer Andorra Mr Ian Harris Australia Mr Georg Posch Austria Mr Kazi Rakibuddin Ahmad Bangladesh Mr Dmitry Shilo Belarus Mr Robert Myttenaere Belgium Mr Georges Brion Belgium Mr Vedran Hadzovik Bosnia & Herzegovina Mr Ognyan Avramov Bulgaria Mr Prosper Vokouma Burkina Faso Mr Carlos Hoffmann Contreras Chile Mr Mateo Sorinas Balfego Council of Europe Mr Brissi Lucas Guehi Cote d’Ivoire Mr Constantinos Christoforou Cyprus Mr Peter Kynstetr Czech Republic Mr Paval Pelant Czech Republic Mr Bourhan Daoud Ahmed Djibouti Mr Farag El-Dory Egypt Mr Samy Mahran Egypt Mr Heike Sibul Estonia Mr Seppo Tiitinen Finland Mr Jean-Claude Becane France Mr Pierre Hontebeyrie France Mrs Hélène Ponceau France Mr Xavier Roques France Mrs Marie-Françoise Pucetti Gabon Mr Felix Owansango Daecken Gabon Mrs Siti Nurhajati Daud Indonesia Mr Arie Hahn Israel Mr Guiseppe Troccoli Italy 2 Mr Amuel Waweru Ndindiri Kenya Mr Sheridah Al-Mosharji Kuwait Mr H Morokole Lesotho Mr Pierre Dillenburg Luxembourg Mr Mamadou Santara Mali Mr Daadankhuu Batbaatar Mongolia Mr Mohamed Idrissi Kaitouni Morocco Mr Carlos Manuel Moxambique Mr Moses Ndjarakana Namibia Mrs Panuleni Shimutwikeni Namibia Mr Bas Nieuwenhuizen Netherlands Mrs Jacqueline Bisheuvel-Vermeijden Netherlands Mr Ibrahim -

ASGP Santiago Plenary Minutes

MINUTES OF THE SPRING SESSION SANTIAGO, CHILE 7 - 11 APRIL 2003 ASSOCIATION OF SECRETARIES GENERAL OF PARLIAMENTS Minutes of the Spring Session 2003 Santiago 7 - 11 April 2003 LIST OF ATTENDANCE MEMBERS PRESENT Mr Hafnaoui Amrani Algeria Mr Valenti Marti Castanyer Andorra Mr Ian Harris Australia Mr Kazi Rakibuddin Ahmad Bangladesh Mr Dmitry Shilo Belarus Mr Robert Myttenaere Belgium Mr Georges Brion Belgium Mr Ognyan Avramov Bulgaria Mr Prosper Vokouma Burkina Faso Mr Eutopio Lima Da Cruz Cape Verde Mr Carlos Hoffmann Contreras Chile Mr Carlos Loyola Opazo Chile Mr Brissi Lucas Guehi Cote d’Ivoire Mr Peter Kynstetr Czech Republic Mr Paval Pelant Czech Republic Mr Asnake Tadesse Ethiopia Mrs Mary Chapman Fiji Mr Jouri Vainio Finland Mr Jean-Claude Becane France Mrs Hélène Ponceau France Mr Xavier Roques France Mrs Marie-Françoise Pucetti Gabon Mr Dirk Brouer Germany Mr Kenneth E K Tachie Ghana Mr Mohamed Salifou Toure Guinea Mr Arteveld Pierre Jerome Haiti Mr Helgi Bernodusson Iceland Mrs Siti Nurhajati Daud Indonesia Mr Arie Hahn Israel Mr Guiseppe Troccoli Italy Dr Mohamad Al-Masalha Jordan Mr Zaid Zuraikat Jordan Mr Amuel Waweru Ndindiri Kenya Mr Mamadou Santara Mali Mr Namsraijav Luvsanjav Mongolia Mr Mohamed Idrissi Kaitouni Morocco Mr Moses Ndjarakana Namibia Mrs Panuleni Shimutwikeni Namibia Mr Bas Nieuwenhuizen Netherlands - 2 - Mrs Jacqueline Bisheuvel-Vermeijden Netherlands Mr Ibrahim Salim Nigeria Mr Hans Brattesta Norway Mr Vladimir Aksyonov Parliamentary Assembly of the Union of Belarus and the Russian Federation Mr Mahmood -

Sổ Tay Thanh Niên Asean 2020

TRUNG ƯƠNG ĐOÀN TNCS HỒ CHÍ MINH - ỦY BAN QUỐC GIA VỀ THANH NIÊN VIỆT NAM SỔ TAY THANH NIÊN ASEAN 2020 (Dành cho cán bộ Đoàn, đoàn viên, thanh niên) MỤC LỤC LỜI NÓI ĐẦU ................................................................................................................5 I. GIỚI THIỆU CHUNG VỀ ASEAN ........................................................................7 1. Quá trình hình thành và phát triển .........................................................................7 2. Định hướng và Nguyên tắc ASEAN ........................................................................8 3. Cơ cấu tổ chức của ASEAN ......................................................................................9 4. Các diễn đàn khu vực do ASEAN khởi xướng và dẫn dắt ..................................11 5. Ngày ASEAN .............................................................................................................13 II. CỘNG ĐỒNG ASEAN 2015 ...............................................................................15 1. Quá trình hình thành ý tưởng ................................................................................15 2. Mục tiêu tổng quát ...................................................................................................15 3. Các Trụ cột của Cộng đồng ASEAN 2015 ............................................................17 4. Ý nghĩa .......................................................................................................................18 III. TẦM NHÌN CỘNG ĐỒNG ASEAN 2025 .......................................................21 -

Message from the Chair Newsletter of the Ifla Section on Library and Research Services for Parliaments

NEWSLETTER OF THE IFLA SECTION ON LIBRARY A ND RESEARCH SERVICES FOR PARLIAMENTS J U L Y 2 0 1 6 MESSAGE FROM THE CHA IR INSIDE THIS ISSUE Dear Colleagues, Message from the Chair 1 Planning for the 32st Annual Pre-Conference of the IFLA Section on Library and Research Services How to join the Section 1 for Parliaments, hosted by the US Library of Congress, is going well. For the first time, the Section had to set a limit on the number of delegates, and we exceeded that number by the time registra- IFLAPARL Pre-conference 2 - 3 2016 tion ended in late April 2016. I wish to thank those who registered for your patience in working with the pre-conference staff to re-confirm your attendance so that we can accommodate those Share and connect 3 who were on the waiting list. At last count, we have confirmed delegates from 54 countries and 7 IFLA WLIC in Columbus, 4 - 5 parliamentary-related organizations. Delegates can expect a very interesting pre-conference pro- Ohio gramme. Recent events 6 - 7 The Section is partnering with the US House Democracy Partnership (HDP) and the National Dem- News from Parliamentary 8 ocratic Institute (NDI) to organize a two-day HDP Parliamentary Staff Institute with funding support Libraries & Research from the US Agency for International Development. Thirty-two delegates from Colombia, Georgia, Services Indonesia, Kenya, Kosovo, Liberia, Macedonia, Myanmar, Peru, Sri Lanka, Timor Leste, Tunisia and Ukraine were selected to participate in the Staff Institute on 8-9 August 2016 in the US Capi- tol. -

Implementation of Knowledge Management: a Comparative Study of the Secretariat of the House of Representatives and the Senate of the Thai Parliament

IMPLEMENTATION OF KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE SECRETARIAT OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND THE SENATE OF THE THAI PARLIAMENT Pakpoom Mingmitr A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Development Administration) School of Public Administration National Institute of Development Administration 2016 ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation Implementation of Knowledge Management: A Comparative Study of the Secretariat of the House of Representatives and the Senate of the Thai Parliament Author: Mr. Pakpoom Mingmitr Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Development Administration) Year: 2016 The problem addressed in this study is that little action is taken to create the value of Knowledge Management (KM) implementation for the Thai Parliament. There is a need to increase the understanding of KM in terms of the characteristics, processes, outcomes, and critical success factors (CSFs) in order to integrate a framework to study KM. The purpose of this study was to investigate the KM elements, in terms of characteristics, processes, outcomes, and the CSFs at the Thai Parliament. The research questions were: 1) How do KM characteristics affect the KM implementation at the Thai Parliament?; 2) How does the parliamentary staff deal with the KM processes at the Thai Parliament?; 3) How can KM outcomes support the KM implementation at the Thai Parliament?; 4) Why has leadership become the most important CSF for the KM success of the Thai Parliament?; and 5) What is the difference between the approach of KM implementation at the Secretariat of the House of Representatives and the Senate of the Thai Parliament?. The overall research design was the qualitative research approach. -

Southeast Asia from the Corner of 18Th & K Streets

Southeast Asia Program Southeast Asia from the Corner of 18th & K Streets Volume III | Issue 15 | August 2, 2012 The President, the Lady, and the Plight of the Rohingya Inside This Issue the week that was gregory poling and prashanth parameswaran Gregory Poling is a research associate with the Southeast Asia • ASEAN releases statement on South China Sea Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in • Thai parliament says reconciliation bills Washington, D.C. Prashanth Parameswaran is a researcher with the off the agenda for opening session CSIS Southeast Asia Program. • Aquino highlights strong economic growth August 2, 2012 in his State of the Nation Address looking ahead Myanmar continues to pursue reforms at an impressive pace, • Conversation with former World but the plight of the country’s Rohingya population remains a Bank president Robert Zoellick disgrace for a state seeking to engage the international community. That disgrace is not the government’s alone—it is shared by the • Discussion with Assistant Secretary opposition movement, including its leader Aung San Suu Kyi as well Andrew Shapiro at CSIS as the country’s neighbors and the international community. • 44th ASEAN Economic Ministers Meeting The more than 800,000 Rohingyas that live in Myanmar today, most in western Rakhine state, are denied citizenship by the government and face a range of abuses including forced labor, marriage restrictions, and unlawful detention. Their suffering is so severe that many have sought refuge across the border in Bangladesh, while others have fled on dangerous voyages by boat to Thailand and Malaysia. Amnesty International July 20 noted that both security forces and Buddhists in Rakhine state have been carrying out “primarily one-sided” attacks, including massive security sweeps, detentions, and killings, against the Rohingya in the weeks after a wave of communal violence erupted between the area’s Buddhist and Muslim populations.