REVISTA CONEXAO POLITICA INGLES ELETRONICA.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Victories for Kirchner LADB Staff

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiSur Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 9-19-2003 New Victories for Kirchner LADB Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur Recommended Citation LADB Staff. "New Victories for Kirchner." (2003). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur/13188 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiSur by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 52610 ISSN: 1089-1560 New Victories for Kirchner by LADB Staff Category/Department: Argentina Published: 2003-09-19 With little more than 100 days in office, Argentine President Nestor Kirchner has new reasons to celebrate. He signed a deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), one day after failing to meet a payment, that most analysts saw as a coup for the president. And, his political strength has increased with the victory of candidates he endorsed in elections in several provinces and the city of Buenos Aires. Kirchner, who marked 100 days in office Sept. 1, has seemed a far cry from recent Argentine political leaders, whether on issues of IMF renegotiations, human rights, relations with the US, trade, or domestic policies. Kirchner continues to enjoy high public support. He has the most prestige of any president in recent years, and few people have much negative to say about him, said political consultant Enrique Zuleta Puceiro of the firm OPSM. In a recent OPSM poll, respondents gave Kirchner high marks for initiative, independence of criteria, and leadership, with percentages near 70%. -

Briefing European Parliamentary Research Service

At a glance September 2015 Argentina: Political parties and the EU Argentina's presidential elections are scheduled for October 2015 and, according to the country's Constitution, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner is not entitled to run for a third consecutive term. As regards alternative candidates, the political landscape remains polarised after the primary elections. Argentina has a multi-party political system; however, election results demonstrate that it is, in practical terms, bipartisan. The Peronists, represented by the Justicialist Party (PJ), and the radicals, represented by the Civic Radical Union (UCR), effectively alternate in power. Argentinian political decision-making is opaque, complex and volatile. Parties play for power in changing coalitions, splits and mergers, which lead to a constantly changing political landscape of alliances. Political and Electoral System The Constitution of Argentina dates back to 1853. It remained in force under the various military regimes, with the exception of the Peronist constitutional period between 1949 and 1956. Over the years, it has been subject to a number of amendments, the most important in 1953, and recently in 1994. Argentina is a federal republic with division of powers. The executive is currently represented by the President, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, from the centre-left Peronist faction, Front For Victory (FPV), which belongs to the Justicialist Party. The President is elected for a four-year term with the possibility of being re-elected for only one consecutive term. Elections take place in two rounds. To be directly elected in the first round, the candidate needs to obtain 45% of the votes cast, or 40% and be 11% ahead of the second candidate. -

The Languages of the Arab Revolutions Abdou Filali-Ansary the Freedom House Survey for 2011 Arch Puddington

April 2012, Volume 23, Number 2 $12.00 The Languages of the Arab Revolutions Abdou Filali-Ansary The Freedom House Survey for 2011 Arch Puddington Tunisia’s Transition and the Twin Tolerations Alfred Stepan Forrest D. Colburn & Arturo Cruz S. on Nicaragua Ernesto Calvo & M. Victoria Murillo on Argentina’s Elections Arthur Goldsmith on “Bottom-Billion” Elections Ashutosh Varshney on “State-Nations” Tsveta Petrova on Polish Democracy Promotion Democracy and the State in Southeast Asia Thitinan Pongsudhirak Martin Gainsborough Dan Slater Donald K. Emmerson ArgentinA: the persistence of peronism Ernesto Calvo and M. Victoria Murillo Ernesto Calvo is associate professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland–College Park. M. Victoria Murillo is profes- sor of political science and international affairs at Columbia Univer- sity and the author of Political Competition, Partisanship, and Policy- making in Latin America (2009). On 23 October 2011, Argentina’s Peronist president Cristina Fernán- dez de Kirchner of the Justicialist Party (PJ) overcame a bumpy first term and comfortably won reelection. She garnered an outright major- ity of 54.1 percent of the popular vote in the first round, besting her 2007 showing by roughly 9 percentage points and avoiding a runoff. Although most observers had expected her to win, the sweeping scale of her victory exceeded the expectations of both her administration and the fragmented opposition. In the most lopsided presidential result since 1928,1 she carried 23 of Argentina’s 24 provinces while her leading rival Hermes Binner, the Socialist governor of Santa Fe Province, collected only 16.8 percent of the national vote. -

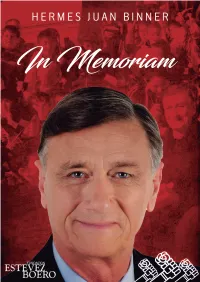

Hermes Binner in Memori

SUMARIO Un socialista más, pero no uno cualquiera Por MARIANO SCHUSTER Y FERNANDO MANUEL SUAREZ ............................................................. 7 Lo que brilla con luz propia nadie lo puede apagar Por GASTÓN D. BOZZANO ......................................................................................................................... 13 El padre de la criatura fue un solista que le dio vuelo propio al socialismo local Por MAURICIO MARONNA ......................................................................................................................... 17 Binner, el médico que inventó la marca Rosario Por LUIS BASTÚS ......................................................................................................................................... 20 Pablo Javkin recordó a Hermes Binner: Rosario ya te extraña y te honra Nota en el diario EL CIUDADANO ............................................................................................................ 22 Hermes Binner, el hombre que no se dejaba apurar por el tiempo Por DAVID NARCISO ................................................................................................................................... 24 Un buen hombre, un mejor amigo Por THOMAS ABRAHAM ............................................................................................................................. 29 Un dirigente que funcionó en modo política 30 años Por DANIEL LEÑINI .................................................................................................................................... -

THE CASE of the ARGENTINE SENATE By

FEDERALISM AND THE LIMITS OF PRESIDENTIAL POWERS: THE CASE OF THE ARGENTINE SENATE by Hirokazu Kikuchi LL.B. in Political Science, Keio University, 2001 LL.M. in Political Science, Keio University, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Hirokazu Kikuchi It was defended on November 2, 2012 and approved by Ernesto F. Calvo, Associate Professor, Department of Government and Politics, University of Maryland Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Jennifer Nicoll Victor, Assistant Professor, Department of Public and International Affairs, George Mason University Dissertation Advisor: Aníbal S. Pérez-Liñán, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science ii Copyright © by Hirokazu Kikuchi 2012 iii FEDERALISM AND THE LIMITS OF PRESIDENTIAL POWERS: THE CASE OF THE ARGENTINE SENATE Hirokazu Kikuchi, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Under what conditions can subnational governments be national veto players? Many studies of federal countries have regarded governors as national veto players even though they do not have such a constitutional status. However, the statistical tests of comparative legislative studies and those of comparative federalism have not succeeded in showing gubernatorial effects on a national political arena. In this dissertation, I study the conditions under which governors can be national veto players by focusing on the treatment of presidential bills between 1983 and 2007 in the Argentine Senate. The dissertation shows that the Senate serves as an arena for subnational governments to influence national politics. -

Argentina: Background and U.S. Relations

Argentina: Background and U.S. Relations Mark P. Sullivan Specialist in Latin American Affairs Rebecca M. Nelson Specialist in International Trade and Finance December 9, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43816 Argentina: Background and U.S. Relations Summary Argentina, a South American country with a population of around 41 million, has had a vibrant democratic tradition since its military relinquished power in 1983. Current President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, from a center-left faction of the Peronist party, was first elected in 2007 (succeeding her husband, Néstor Kirchner, who served one term) and is now approaching the final year of her second term. Argentina’s constitution does not allow for more than two successive terms, so President Fernández is ineligible to run in the next presidential election, scheduled for October 2015. The presidential race is well underway with several candidates leading opinion polls, including two from the Peronist party. Argentina has Latin America’s third-largest economy and is endowed with vast natural resources. Agriculture has traditionally been a main economic driver, but the country also has a diversified industrial base and a highly educated population. In 2001-2002, a severe economic crisis precipitated by unsustainable debt led to the government defaulting on nearly $100 billion in foreign debt owed to private creditors, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and foreign governments. Subsequent Argentine administrations resolved more than 90% of the country’s debt owed to private creditors through two debt restructurings offered in 2005 and 2010; repaid debt owed to the IMF in 2006; and, in May 2014, reached an agreement to repay foreign governments. -

Crisis, Boom, and the Restructuring of the Argentine Party System (1999-2015)

Crisis, Boom, and the Restructuring of the Argentine Party System (1999-2015) María Victoria Murillo and Steven Levitsky Mauricio Marci’s victory in Argentina’s 2015 presidential election was, in many senses, historic. Macri, the former mayor of the City of Buenos Aires and founder of the center-right Republican Proposal (PRO), was the first right wing candidate—and the first candidate not from the (Peronist) Justicialista Party (PJ) or the Radical Civic Union (UCR)--ever to win a democratic presidential election in Argentina. From a regional perspective, Macri’s victory suggested that Latin America’s so-called Left Turn—the extraordinary wave of left-of-center governments that began with Hugo Chávez’s 1998 election in Venezuela and swept across Chile (2000, 2006, 2014), Brazil (2002, 2006, 2010, 2014), Argentina (2003, 2007, 2011), Uruguay (2004, 2009, 2014), Bolivia (2005, 2009, 2014), Ecuador (2006, 2009, 2013), Nicaragua (2006, 2011), Guatemala (2008), Paraguay (2008), El Salvador (2009, 2014), and Costa Rica (2014)— was ending. Indeed, some observers pointed to Macri’s election as the beginning of a “Right Turn” in the region. This chapter suggests that although Macri’s surprising victory may be part of a broader regional turn, it is better understood as an “anti-incumbent turn” than as a turn to the Right. It argues that this shift was driven primarily by economic conditions, particularly the end of the 2002-2014 commodities boom.1 The Latin American Left, including Peronist Presidents Nestor and Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, had benefited from global economic conditions in two 1 Building on the existing literature on economic voting in Latin America, Murillo and Visconti (2016) show the impact of economic conditions—including growth, inflation, and reserve levels—on changes in support for incumbent parties in Latin America since the transition to democracy. -

Curtains for Argentina's Kirchner

“In 2014, the currency devaluation and inflationary spike dented the president’s popularity and eroded perceptions of her government’s economic competence.” Curtains for Argentina’s Kirchner Era M. VICTORIA MURILLO ristina Fernández de Kirchner, the third please voters. Deteriorating economic conditions Peronist to be elected president of Argen- will make it harder for any successor to Fernández Ctina since the democratic transition of de Kirchner to adopt left-wing policies, even if he 1983, is approaching the end of her second term. or she wanted to. Her presidency followed that of her husband Nés- The surprise of this final act is that she has man- tor Kirchner (2003–7). After a dozen years with aged to keep the political initiative, moving to reg- one Kirchner or the other at the helm, Argentina ulate the oil sector, reform telecommunications, is facing a presidential election in October with and revise the civil and criminal codes. A lame- considerably more uncertainty than the past two, duck president in the last year of her mandate which Fernández de Kirchner won in overwhelm- could easily have lost that capacity for action, es- ing landslides. pecially in the context of an economic slowdown, There is no clear front-runner this time. How- increasing unemployment, and high inflation. Ad- ever, any of the three candidates with a higher ditionally, she lacks a loyal successor—a candidate probability of winning is likely to steer the next with a good chance of winning the next election administration toward more moderate economic and sustaining her brand of politics, known as policies, including some kind of fiscal adjustment, Kirchnerism, into the future. -

Argentina After the Elections1

28 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 1|2012 ArgentinA After 1 the elections President Kirchner embArKs on her second term of office with A strengthened mAndAte Dr. Bernd Löhmann is Bernd Löhmann Resident Represen- tative of the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung in Argentina. With the country-wide primaries on 14 August 2011 and the general election on 23 October, Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner has in effect been twice confirmed in office. She was re-elected with around 54 per cent of the votes cast. In the concurrent congres- sional elections, at which half the seats in the Chamber of Deputies and a third of the seats in the Senate were up for renewal, the Peronist election platform “Frente para la Victoria” (FPV) that backs her also emerged victorious. The FPV, with the parties allied to it, has thus regained the majority in both houses. In addition, governors and parlia- ments were elected in most provinces. In almost all cases the winners were forces allied to the national government; only in three of the 24 federal units are parties openly opposed to the FPV. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s victory has been aptly described as a “tsunami”. Boosted by the outcome of two elections, the President now wields far more political weight than any of her predecessors since Argentina’s return to democracy. Even her husband, who was president of Argentina from 2003 until 2007 and was regarded until his death in October 2010 as the real leader of Argentine politics, was never able to rely on such a broad legitimation and power base. -

Recent Experiences and Perceptions of South American Migrants in Argentina Under MERCOSUR

Université de Montréal ‘Are We Now Equal?’ Recent Experiences and Perceptions of South American Migrants in Argentina under MERCOSUR par Aranzazu Recalde Département d’anthropologie Faculté des arts et des sciences Thèse présentée à la Faculté des arts et des sciences en vue de l’obtention du grade de philosophiæ doctor (Ph.D.) en anthropologie Novembre, 2012 © Aranzazu Recalde, 2012 Université de Montréal Faculté des arts et des sciences Cette thèse intitulée : ‘Are We Now Equal?’ Recent Experiences and Perceptions of South American Migrants in Argentina under MERCOSUR présentée par Aranzazu Recalde a été évaluée par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : Jorge Pantaleón Président-rapporteur Deirdre Meintel Directeur de recherche Josiane Le Gall Membre du jury Lindsay Dubois Évaluateur externe Patricia Lamarre Représentant du doyen Résumé De manière générale, ma thèse examine les mécanismes des processus sociaux, économiques et politiques ayant contribué, souvent de manière contradictoire, à la (re)définition des critères d’adhésion au sein de la nation et de l’Etat. Elle le fait par le dialogue au sein de deux grands corps de littérature intimement liés, la citoyenneté et le transnationalisme, qui se sont penchés sur les questions d’appartenance, d’exclusion, de mobilité et d’accès aux droits chez les migrants transnationaux tout en soulignant la capacité accrue de l’Etat à réguler à la fois les déplacements de personnes et l’accès des migrants aux droits. Cette thèse remet en question trois principes qui influencent la recherche et les programmes d’action publique ayant trait au transnationalisme et à la citoyenneté des migrants, et remet en cause les approches analytiques hégémoniques et méthodologiques qui les sous-tendent. -

Promoting a National Policy Forum: CIPPEC’S “Agenda for the President 2011-2015”

Influence, Monitoring and Evaluation Program Area of Institutions and Public Management THINK TANKS’ SERIES N° 1 DECEMBER 2013 Promoting a national policy forum: CIPPEC’s “Agenda for the President 2011-2015” LEANDRO ECHT | AGUSTINA ESKENAZI Index Index..................................................................................................................................................................2 Executive summary.........................................................................................................................................3 1. Background ..................................................................................................................................................4 2. Rationality....................................................................................................................................................5 3. Strategies ......................................................................................................................................................6 3.1. Strategy I: Making of the Memos....................................................................................................6 3.2. Strategy II: Outreach Campaign .....................................................................................................8 3.3. Strategy III: Political Advocacy Campaign .................................................................................10 4. Balance ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Electricity Policy in Argentina and Uruguay

Explaining Divergent Energy Paths: Electricity Policy in Argentina and Uruguay Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Politikwissenschaften (Dr. rer. pol.) am Fachbereich Politik- und Sozialwissenschaften des Otto-Suhr-Institutes der Freien Universität Berlin Vorgelegt im Jahr 2014 von Moïra Jimeno Supervisor: Prof. Miranda Schreurs, Ph.D. Second Supervisor: PD. Dr. Achim Brunnengräber Date of the Defense: October 14, 2014 Berlin Table of contents i List of Tables v List of Figures v Acronyms vii Acknowledgements xi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Definition of the research topic 1 1.2 State of the Art 7 1.2.1 Empirical Importance of Electricity Policy in Argentina and Uruguay 7 1.2.2 Theoretical and Practical Interest 12 1.3 Research Questions 13 1.4 Structure of the Work 14 2 Theoretical and Analytical Framework 17 2.1 Actors, Advocacy Coalitions, and Policy Subsystems 17 2.2 Policy Beliefs, Ideas, Perception and Interests 19 2.3 Advocacy Coalitions and Punctuated Equilibrium 27 2.4 Historical Institutionalism: Importance of Policy Change and Path Dependency 30 2.5 Analytical Framework 37 2.5.1 Definition of the Hypotheses 40 3 Methodological Framework 49 3.1 Methodological Approach 49 3.2 Election of the two-case studies and the period of time 51 3.3 Sources of evidence for the two-case studies 53 4 Political Contexts of Argentina and Uruguay 57 4.1 Introduction 57 4.2 The political context of Argentina and Uruguay 58 4.3 Natural Resources and Economic Development in Latin America 63 4.4 International Policy Learning