Electricity Policy in Argentina and Uruguay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Victories for Kirchner LADB Staff

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiSur Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 9-19-2003 New Victories for Kirchner LADB Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur Recommended Citation LADB Staff. "New Victories for Kirchner." (2003). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur/13188 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiSur by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 52610 ISSN: 1089-1560 New Victories for Kirchner by LADB Staff Category/Department: Argentina Published: 2003-09-19 With little more than 100 days in office, Argentine President Nestor Kirchner has new reasons to celebrate. He signed a deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), one day after failing to meet a payment, that most analysts saw as a coup for the president. And, his political strength has increased with the victory of candidates he endorsed in elections in several provinces and the city of Buenos Aires. Kirchner, who marked 100 days in office Sept. 1, has seemed a far cry from recent Argentine political leaders, whether on issues of IMF renegotiations, human rights, relations with the US, trade, or domestic policies. Kirchner continues to enjoy high public support. He has the most prestige of any president in recent years, and few people have much negative to say about him, said political consultant Enrique Zuleta Puceiro of the firm OPSM. In a recent OPSM poll, respondents gave Kirchner high marks for initiative, independence of criteria, and leadership, with percentages near 70%. -

Facultad De Ciencias Económicas Y Empresariales

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS Y EMPRESARIALES THE GREEN FUTURE OF ELECTRICITY: THE CASES OF URUGUAY AND THE EUROPEAN UNION Diego Aboal, Manuel Garcia Goñi, Martin Pereyra, Luis Rubalcaba and Gonzalo Zunino Working Papers / Documentos de Trabajo. ISSN: 2255-5471 DT CCEE-1901 Abril 2019 First Draft http://eprints.ucm.es/ 56240/ Aviso para autores y normas de estilo: http://economicasyempresariales.ucm.es/working-papers-ccee Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons: Reconocimiento - No comercial. THE GREEN FUTURE OF ELECTRICITY: THE CASES OF URUGUAY AND THE EUROPEAN UNION Abstract: The objective of this paper is to understand the policy and regulation changes in Uruguay and the European Union that led to the adoption of non-conventional renewable sources of energy in a short time span. Uruguay is one of only 3 countries in the world with more tan 90% of the electricity coming from renewable sources (98% in Uruguay) and where nonconventional renewables provide a significant contribution to it. Uruguay has also recently launched the first electric route in Latin America, with 500 Km and charging stations at 60 Km intervals. The European Union is an international reference in the promotion of sustainable economic growth and sustainable development. Therefore, we will also look at the experience of the European Union in the development of a green agenda where renewable sources of energy are a fundamental part of it. Keywords: Electricity, Non-conventional Renewable Sources of Energy, Energy Policy, Energy Regulation, Uruguay, European Union. EL FUTURO VERDE DE LA ELECTRICIDAD: LOS CASOS DE URUGAY Y LA UNIÓN EUROPEA Resumen: El objetivo de este trabajo es entender los cambios de política y regulación en Uruguay y la Unión Europea que llevaron a la adopción de fuentes de energía renovable no convencionales en un corto período de tiempo. -

07/2018 REFORM of the RENEWABLE ENERGY DIRECTIVE a Brake on the European Energy Transition?

DISKURS 07/ 2018 Uwe Nestle REFORM OF THE RENEWABLE ENERGY DIRECTIVE A Brake On The European Energy Transition? WISO DISKURS 07/ 2018 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) is the oldest political foundation in Germany with a rich tradition dating back to its foundation in 1925. Today, it remains loyal to the legacy of its namesake and campaigns for the core ideas and values of social democracy: freedom, justice and solidarity. It has a close connection to social democracy and free trade unions. FES promotes the advancement of social democracy, in particular by: – Political educational work to strengthen civil society; – Think Tanks; – International cooperation with our international network of offices in more than 100 countries; – Support for talented young people; – Maintaining the collective memory of social democracy with archives, libraries and more. The Division for Economic and Social Policy The Division for Economic and Social Policy of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung advises and informs politics and society in Germany about important current issues and policy making concerning social, economic and environmental developments. WISO Diskurs WISO Diskurs are detailed analyses examining political issues and questions, containing sound policy recommendations and contributing to scientifically based policy consultation. About the author Uwe Nestle is the founder of EnKliP (Energy and Climate Policy I Contracting). He served in the German Federal Environment Ministry for about ten years, working on the energy transition and in particular renewable energy. Responsible for this Publication at FES Dr. Philipp Fink is head of the sustainable structural policy working group and the climate, environment, energy and structural policy desk in the Division for Economic and Social Policy at Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. -

Megatrends in the Global Energy Transition

Megatrends in the global energy transition Legal notice Published by WWF Germany and LichtBlick SE November 2015 Author Gerd Rosenkranz Data verification Jürgen Quentin Coordination Viviane Raddatz/WWF Germany Corine Veithen/LichtBlick SE Edited by Gerd Rosenkranz, Jürgen Quentin, LichtBlick, WWF Germany Contact [email protected] [email protected] Design Thomas Schlembach/WWF Germany Infographics Anita Drbohlav/www.paneemadesign.com Production Maro Ballach/WWF Germany The leading renewable energy supplier LichtBlick and the conservation organisation WWF Germany are working together to speed up the energy transition in Germany. They pursue a common aim of inspiring people for change and of drawing attention to the enormous opportunities for a renewable energy future. www.energiewendebeschleunigen.de Introduction It was a surprising statement for an important summit: in Schloss Elmau, Bavaria at the beginning of June 2015, the G7 heads of state and government announced the global withdrawal from the carbon economy. As the century progresses, the world must learn to do without lignite, coal, oil and natural gas completely. In truth this aim is not only urgently needed in order to stem the dangers of climate change, but also achievable. The energy transition has become a massive global force, expansion of renewables is making progress worldwide faster than even the optimists believed a few years ago. This report provides wide-ranging evidence that the global conversion of the energy system has started and is currently accelerating rapidly. It shows that renewable energies – and solar energy in particular – have undergone an unparalleled development: from a niche technology rejected as being too expensive to a global competitor for fossil and nuclear power plants. -

100% Renewable Electricity: a Roadmap to 2050 for Europe

100% renewable electricity A roadmap to 2050 for Europe and North Africa Available online at: www.pwc.com/sustainability Acknowledgements This report was written by a team comprising individuals from PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC), the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and the European Climate Forum (ECF). During the development of the report, the authors were provided with information and comments from a wide range of individuals working in the renewable energy industry and other experts. These individuals are too numerous to mention, however the project team would like to thank all of them for their support and input throughout the writing of this report. Contents 1. Foreword 1 2. Executive summary 5 3. 2010 to 2050: Today’s situation, tomorrow’s vision 13 3.1. Electricity demand 15 3.2. Power grids 15 3.3. Electricity supply 18 3.4. Policy 26 3.5. Market 30 3.6. Costs 32 4. Getting there: The 2050 roadmap 39 4.1. The Europe - North Africa power market model 39 4.2. Roadmap planning horizons 41 4.3. Introducing the roadmap 43 4.4. Roadmap enabling area 1: Policy 46 4.5. Roadmap enabling area 2: Market structure 51 4.6. Roadmap enabling area 3: Investment and finance 54 4.7. Roadmap enabling area 4: Infrastructure 58 5. Opportunities and consequences 65 5.1. Security of supply 65 5.2. Costs 67 5.3. Environmental concerns 69 5.4. Sustainable development 70 5.5. Addressing the global climate problem 71 6. Conclusions and next steps 75 PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP Appendices Appendix 1: Acronyms and Glossary 79 Appendix 2: The 2050 roadmap in detail 83 Appendix 3: Cost calculations and assumptions 114 Appendix 4: Case studies 117 Appendix 5: Taking the roadmap forward – additional study areas 131 Appendix 6: References 133 Appendix 7: Contact information 138 PricewaterhouseCoopers LLPP Chapter one: Foreword 1. -

Briefing European Parliamentary Research Service

At a glance September 2015 Argentina: Political parties and the EU Argentina's presidential elections are scheduled for October 2015 and, according to the country's Constitution, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner is not entitled to run for a third consecutive term. As regards alternative candidates, the political landscape remains polarised after the primary elections. Argentina has a multi-party political system; however, election results demonstrate that it is, in practical terms, bipartisan. The Peronists, represented by the Justicialist Party (PJ), and the radicals, represented by the Civic Radical Union (UCR), effectively alternate in power. Argentinian political decision-making is opaque, complex and volatile. Parties play for power in changing coalitions, splits and mergers, which lead to a constantly changing political landscape of alliances. Political and Electoral System The Constitution of Argentina dates back to 1853. It remained in force under the various military regimes, with the exception of the Peronist constitutional period between 1949 and 1956. Over the years, it has been subject to a number of amendments, the most important in 1953, and recently in 1994. Argentina is a federal republic with division of powers. The executive is currently represented by the President, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, from the centre-left Peronist faction, Front For Victory (FPV), which belongs to the Justicialist Party. The President is elected for a four-year term with the possibility of being re-elected for only one consecutive term. Elections take place in two rounds. To be directly elected in the first round, the candidate needs to obtain 45% of the votes cast, or 40% and be 11% ahead of the second candidate. -

Wind Power a Victim of Policy and Politics

NNoottee ddee ll’’IIffrrii Wind Power A Victim of Policy and Politics ______________________________________________________________________ Maïté Jauréguy-Naudin October 2010 . Gouvernance européenne et géopolitique de l’énergie The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non- governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. ISBN: 978-2-86592-780-7 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2010 IFRI IFRI-BRUXELLES 27, RUE DE LA PROCESSION RUE MARIE-THERESE, 21 75740 PARIS CEDEX 15 – FRANCE 1000 – BRUXELLES – BELGIQUE Tel: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tel: +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Fax: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Fax: +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] WEBSITE: Ifri.org Executive Summary In December 2008, as part of the fight against climate change, the European Union adopted the Energy and Climate package that endorsed three objectives toward 2020: a 20% increase in energy efficiency, a 20% reduction in GHG emissions (compared to 1990), and a 20% share of renewables in final energy consumption. -

Wind-Power Development in Germany and the U.S.: Structural Factors, Multiple-Stream Convergence, and Turning Points

1 Wind-Power Development in Germany and the U.S.: Structural Factors, Multiple-Stream Convergence, and Turning Points a chapter in Andreas Duit, ed., State and Environment: The Comparative Study of Environmental Governance [tentative title] Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, forthcoming in 2014 Roger Karapin Department of Political Science Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center New York, USA Email: [email protected] May 2013 final draft Introduction Renewable energy is seen as a solution to problems of anthropogenic climate change, air pollution, resource scarcity, and dependence on energy imports (Vasi 2009; IPCC 2012). Of the various forms of renewable energy, wind-generated electricity has a unique set of advantages, which make its potential environmental benefits especially large. Wind power produces relatively low levels of environmental damage over its life cycle (like solar), 1 relies on relatively mature technology, and already comprises a nontrivial share of energy production (like hydro and biomass). It is also based on a potentially enormous natural resource and has been growing rapidly in many industrialized and developing countries (Greene, et al. 2010). Global installed capacity of wind power rose an average of 25% a year from 2001 to 2012, to a total of 282,000 Megawatts (MW), and wind power now generates about 3% of global electricity consumption (data from World Wind Energy Association and BP 2012). 2 Although common experiences with the oil crises of the 1970s and more recent concerns 2 about global warming have motivated most industrialized countries to adopt wind-power development policies, they vary greatly in the extent to which they have successfully developed this renewable-energy source. -

The Languages of the Arab Revolutions Abdou Filali-Ansary the Freedom House Survey for 2011 Arch Puddington

April 2012, Volume 23, Number 2 $12.00 The Languages of the Arab Revolutions Abdou Filali-Ansary The Freedom House Survey for 2011 Arch Puddington Tunisia’s Transition and the Twin Tolerations Alfred Stepan Forrest D. Colburn & Arturo Cruz S. on Nicaragua Ernesto Calvo & M. Victoria Murillo on Argentina’s Elections Arthur Goldsmith on “Bottom-Billion” Elections Ashutosh Varshney on “State-Nations” Tsveta Petrova on Polish Democracy Promotion Democracy and the State in Southeast Asia Thitinan Pongsudhirak Martin Gainsborough Dan Slater Donald K. Emmerson ArgentinA: the persistence of peronism Ernesto Calvo and M. Victoria Murillo Ernesto Calvo is associate professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland–College Park. M. Victoria Murillo is profes- sor of political science and international affairs at Columbia Univer- sity and the author of Political Competition, Partisanship, and Policy- making in Latin America (2009). On 23 October 2011, Argentina’s Peronist president Cristina Fernán- dez de Kirchner of the Justicialist Party (PJ) overcame a bumpy first term and comfortably won reelection. She garnered an outright major- ity of 54.1 percent of the popular vote in the first round, besting her 2007 showing by roughly 9 percentage points and avoiding a runoff. Although most observers had expected her to win, the sweeping scale of her victory exceeded the expectations of both her administration and the fragmented opposition. In the most lopsided presidential result since 1928,1 she carried 23 of Argentina’s 24 provinces while her leading rival Hermes Binner, the Socialist governor of Santa Fe Province, collected only 16.8 percent of the national vote. -

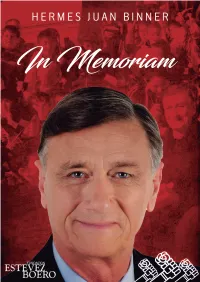

Hermes Binner in Memori

SUMARIO Un socialista más, pero no uno cualquiera Por MARIANO SCHUSTER Y FERNANDO MANUEL SUAREZ ............................................................. 7 Lo que brilla con luz propia nadie lo puede apagar Por GASTÓN D. BOZZANO ......................................................................................................................... 13 El padre de la criatura fue un solista que le dio vuelo propio al socialismo local Por MAURICIO MARONNA ......................................................................................................................... 17 Binner, el médico que inventó la marca Rosario Por LUIS BASTÚS ......................................................................................................................................... 20 Pablo Javkin recordó a Hermes Binner: Rosario ya te extraña y te honra Nota en el diario EL CIUDADANO ............................................................................................................ 22 Hermes Binner, el hombre que no se dejaba apurar por el tiempo Por DAVID NARCISO ................................................................................................................................... 24 Un buen hombre, un mejor amigo Por THOMAS ABRAHAM ............................................................................................................................. 29 Un dirigente que funcionó en modo política 30 años Por DANIEL LEÑINI .................................................................................................................................... -

The Legitimacy of Wind Power in Germany

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Dehler-Holland, Joris; Okoh, Marvin; Keles, Dogan Working Paper The legitimacy of wind power in Germany Working Paper Series in Production and Energy, No. 54 Provided in Cooperation with: Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Institute for Industrial Production (IIP) Suggested Citation: Dehler-Holland, Joris; Okoh, Marvin; Keles, Dogan (2021) : The legitimacy of wind power in Germany, Working Paper Series in Production and Energy, No. 54, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Institute for Industrial Production (IIP), Karlsruhe, http://dx.doi.org/10.5445/IR/1000128597 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/229440 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu The Legitimacy of Wind Power in Germany by Joris Dehler-Holland, Marvin Okoh, Dogan Keles No. -

Patricia Tuomela-Millan Fair Trade Between Uruguay

PATRICIA TUOMELA-MILLAN FAIR TRADE BETWEEN URUGUAY AND FINLAND Business Opportunities Thesis Autumn 2009 Seinäjoki University of Applied Sciences Business School International Business 2 SEINÄJOKI UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Thesis abstract Faculty: Business School Degree programme: Degree Program in International Business Specialisation: International Business Author/s: Patricia Tuomela-Millan Title of thesis: Fair Trade between Uruguay and Finland. Business Opportunities Supervisor(s): Prof. Jorge Marchini Year: 2009 Number of pages: 59 Number of appendices: 3 _________________________________________________________________ The purpose of the final thesis was to find out potential business opportunities un- der the Fair-trade philosophy between Uruguay and Finland. Why Fair Trade and what products could be more interesting to commercialize. The first objective was to describe general information about both countries. The second objective was to introduce and analyze the Fair-trade and its development in both countries. The third objective was to find out the products that could be more interesting to the Finnish Fair-trade. The final thesis consists of two theoretical parts, one analysis and a study case. The history, culture and society, the economy and the bilateral treaties between the two countries make up the first part. The second part is focused on Fair-trade and its development in both countries along with an analysis of it. The third part is focused on Agrarian Cooperative of Canelones “CALCAR” study case in Uruguay with the aim to study the commercialization and market entry opportunities in the Finnish Fair-trade. As a result of the investigation it can be said that Finnish Fair-trade has a very sol- id structure and is constantly growing.