Shia Islam and the Iranian Revolution Written by Nathan Olsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion and Politics

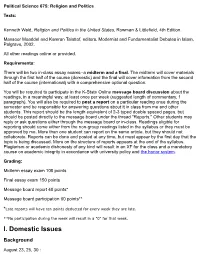

Political Science 675: Religion and Politics Texts: Kenneth Wald, Religion and Politics in the United States, Rowman & Littlefield, 4th Edition. Mansoor Moaddel and Kamran Talattof, editors, Modernist and Fundamentalist Debates in Islam, Palgrave, 2002. All other readings online or provided. Requirements: There will be two in-class essay exams--a midterm and a final. The midterm will cover materials through the first half of the course (domestic) and the final will cover information from the second half of the course (international) with a comprehensive optional question. You will be required to participate in the K-State Online message board discussion about the readings, in a meaningful way, at least once per week (suggested length of commentary, 1 paragraph). You will also be required to post a report on a particular reading once during the semester and be responsible for answering questions about it in class from me and other students. This report should be the length equivalent of 2-3 typed double spaced pages, but should be posted directly to the message board under the thread "Reports." Other students may reply or ask questions either through the message board or in-class. Readings eligible for reporting should come either from the non-group readings listed in the syllabus or they must be approved by me. More than one student can report on the same article, but they should not collaborate. Reports can be done and posted at any time, but must appear by the first day that the topic is being discussed. More on the structure of reports appears at the end of the syllabus. -

The Iranian Revolution, Past, Present and Future

The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Dr. Zayar Copyright © Iran Chamber Society The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Content: Chapter 1 - The Historical Background Chapter 2 - Notes on the History of Iran Chapter 3 - The Communist Party of Iran Chapter 4 - The February Revolution of 1979 Chapter 5 - The Basis of Islamic Fundamentalism Chapter 6 - The Economics of Counter-revolution Chapter 7 - Iranian Perspectives Copyright © Iran Chamber Society 2 The Iranian Revolution Past, Present and Future Chapter 1 The Historical Background Iran is one of the world’s oldest countries. Its history dates back almost 5000 years. It is situated at a strategic juncture in the Middle East region of South West Asia. Evidence of man’s presence as far back as the Lower Palaeolithic period on the Iranian plateau has been found in the Kerman Shah Valley. And time and again in the course of this long history, Iran has found itself invaded and occupied by foreign powers. Some reference to Iranian history is therefore indispensable for a proper understanding of its subsequent development. The first major civilisation in what is now Iran was that of the Elamites, who might have settled in South Western Iran as early as 3000 B.C. In 1500 B.C. Aryan tribes began migrating to Iran from the Volga River north of the Caspian Sea and from Central Asia. Eventually two major tribes of Aryans, the Persian and Medes, settled in Iran. One group settled in the North West and founded the kingdom of Media. The other group lived in South Iran in an area that the Greeks later called Persis—from which the name Persia is derived. -

Not for Distribution

6 The decline of the legitimate monopoly of violence and the return of non-state warriors Cihan Tuğal Introduction For the last few decades, political sociology has focused on state-making. We are therefore quite ill equipped to understand the recent rise of non-state violence throughout the world. Even if states still seem to perform more violence than non- state actors, the latter’s actions have come to significantly transform relationships between citizens and states. Existing frameworks predispose scholars to treat non-state violence too as an instrument of state-building. However, we need to consider whether non-state violence serves other purposes as well. This chapter will first point out how the post-9/11 world problematises one of sociology’s major assumptions (the state’s monopolisation of legitimate violence). It will then trace the social prehistory of non-state political violence to highlight continui- ties with today’s intensifying religious violence. It will finally emphasise that the seemingly inevitable rise of non-state violence is inextricably tangled with the emergence of the subcontracting state. Neo-liberalisation aggravates the practico- ethical difficulties secular revolutionaries and religious radicals face (which I call ‘the Fanonite dilemma’ and ‘the Qutbi dilemma’). The monopolisation of violence: social implications War-making, military apparatuses and international military rivalry figure prominently in today’s political sociology. This came about as a reaction to the sociology and political science of the postwar era: for quite different rea- sons, both tended to ignore the influence of militaries and violence on domestic social structure. Political science unduly focused on the former and sociology on the latter, whereas (according to the new political sociology) international violence and domestic social structure are tightly linked (Mann 1986; Skocpol 1979; Tilly 1992). -

Revolution in Bad Times

asef bayat REVOLUTION IN BAD TIMES ack in 2011, the Arab uprisings were celebrated as world- changing events that would re-define the spirit of our political times. The astonishing spread of these mass uprisings, fol- lowed soon after by the Occupy protests, left observers in Blittle doubt that they were witnessing an unprecedented phenomenon— ‘something totally new’, ‘open-ended’, a ‘movement without a name’; revolutions that heralded a novel path to emancipation. According to Alain Badiou, Tahrir Square and all the activities which took place there—fighting, barricading, camping, debating, cooking and caring for the wounded—constituted the ‘communism of movement’; posited as an alternative to the conventional liberal-democratic or authoritar- ian state, this was a universal concept that heralded a new way of doing politics—a true revolution. For Slavoj Žižek, only these ‘totally new’ political happenings, without hegemonic organizations, charismatic leaderships or party apparatuses, could create what he called the ‘magic of Tahrir’. For Hardt and Negri, the Arab Spring, Europe’s indignado protests and Occupy Wall Street expressed the longing of the multitude for a ‘real democracy’, a different kind of polity that might supplant the hopeless liberal variety worn threadbare by corporate capitalism. These movements, in sum, represented the ‘new global revolutions’.1 ‘New’, certainly; but what does this ‘newness’ tell us about the nature of these political upheavals? What value does it attribute to them? In fact, just as these confident appraisals were being circulated in the us and Europe, the Arab protagonists themselves were anguishing about the fate of their ‘revolutions’, lamenting the dangers of conservative restora- tion or hijacking by free-riders. -

The Sociology of Social Movements

CHAPTER 2 The Sociology of Social Movements CHAPTER OBJECTIVES • Explain the important role of social movements in addressing social problems. • Describe the different types of social movements. • Identify the contrasting sociological explanations for the development and success of social movements. • Outline the stages of development and decline of social movements. • Explain how social movements can change society. 9781442221543_CH02.indd 25 05/02/19 10:10 AM 26 \ CHAPTER 2 AFTER EARNING A BS IN COMPUTER ENGINEERING from Cairo University and an MBA in marketing and finance from the American University of Egypt, Wael Ghonim became head of marketing for Google Middle East and North Africa. Although he had a career with Google, Ghonim’s aspiration was to liberate his country from Hosni Mubarak’s dictatorship and bring democracy to Egypt. Wael became a cyber activist and worked on prodemocracy websites. He created a Facebook page in 2010 called “We are all Khaled Said,” named after a young businessman who police dragged from an Internet café and beat to death after Said exposed police corruption online. Through the posting of videos, photos, and news stories, the Facebook page rapidly became one of Egypt’s most popular activist social media outlets, with hundreds of thousands of followers (BBC 2011, 2014; CBS News 2011). An uprising in nearby Tunisia began in December 2010 and forced out its corrupt leader on January 14, 2011. This inspired the thirty-year-old Ghonim to launch Egypt’s own revolution. He requested through the Facebook page that all of his followers tell as many people as possible to stage protests for democracy and against tyranny, corruption, torture, and unemployment on January 25, 2011. -

Human Rights in Iran Under the Shah

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 7 1980 Human Rights in Iran under the Shah Richard W. Cottam Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard W. Cottam, Human Rights in Iran under the Shah, 12 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 121 (1980) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol12/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Volume 12, Number 1, Winter 1980 COMMENT Human Rights in Iran Under the Shah by Professor Richard W. Cottam* I. INTRODUCTION FOR ANY ADVOCATE of human rights, the events surrounding the Iranian revolution must be a source of continuing agony. But for any- one interested in gaining a sharper understanding of some of the basic issues concerning human rights, the dramatic developments in Iran should be highly instructive. The early summary executions in Iran and the later public trials conducted by revolutionary Islamic courts were properly condemned by western human rights advocates as failing to ap- proach the requirements of due process. Yet the great majority of those who were tried and executed were charged with terrible violations of the most elemental human rights; and the testimony of the accused, so rich in detail and so internally consistent as to be credible,1 tends to confirm the worst charges against the Shah's regime. -

Documents of the Iranian Revolutionary Movement

the time of this writing. The Revo- knee-jerk anti-clericalism. Islam rep- governments fell: first the Bazar- lutionary Guards did attack the resents a third force in the region, gan/Yazdi regime which was pre- offices of the People's Mojahedin one which is opposed to the interests sumed to be secretly pro-U.S. Organization of Iran (OMPI) and of both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. It (Ibrahim Yazdi's secret meeting with the OIPFG: the OMPI placed an would not have been able to make Zbigniew Brzezinski led many to armed guard around its office and the gains which it has made if it conclude that he was the CIA's succeeded in defending it, and while were wholly reactionary and main conduit in the Iranian inner the OIPFG headquarters were anachronistic. Obviously it is circle); then the "moderate" gov- indeed burned, that did not hold inadequate to the broader revolu- ernment of Abol-Hassan Bani-Sadr. back their growth and influence. tionary current and obviously it Now Khomeini's longtime loyalist, The OIPFG and the Workers Syn- imposes fetters on those very forces Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, is feeling the dicates jointly sponsored a Mayday which it releases — the clearest heat. demonstration which attracted examples are the repression of Thus far Khomeini himself has 500,000 people. During the last few women and homosexuals and sex- embraced the revolutionary fervor, weeks, huge crowds have marched uality in general. But the left brings and his public statements have all openly in Tehran under the banners no credit on itself for its failure to supported the students. -

Iran: Suppression of Religious Freedom and Persecution of Religious Minorities

IJRF Vol 2:1 2009 (111-130) 111 Iran: Suppression of religious freedom and persecution of religious minorities Thomas Schirrmacher* Abstract The article explores the situation of non-Shiite Muslims, non-Christian religions like Baha'i, and the different Christian confessions in Iran. It particularly examines their legal situation, asks for the ideological position of the Iranian leadership concerning other religions and then describes the actual problems, as the government rarely uses legal means against other religions, but uses allegations of espionage against them. Keywords Iran, Shia, Sunni, Baha’i, Protestants, Evangelicals. 1. The Iranian revolution Shah Reza Pahlavi maintained progressive economic policies while relying heavily on the West. Unpopular because of his use of repressive measures and his secret service, he was subsequently deposed of by the Shiite Islamic revolution. In 1979 the Islamic Republic was proclaimed. Ever since the Islamic clergy, as guardians of the revolution, maintain authority over the politicians, who, while mostly democratically elected, are hand-picked by the religious guardians. Consequently, in spite of its democratic structures, Iran remains a theocratic police state which ignores human rights, in particular those of minorities, non-Muslims and women. Year after year, the classical reference works which categorize countries according to their religious freedom1 and the persecution of * Prof Dr phil Dr theol Thomas Schirrmacher (*1960) is the Principal of the Martin Bucer Seminary (Bonn, Zürich, Innsbruck, Prague, Ankara); professor of sociology of religion at the State University of Oradea, Romania; director of the International Institute for Religious Freedom of the World Evangelical Alliance and Speaker for Human Rights of this worldwide network. -

The Mujahedin-E Khalq in Iraq: a Policy Conundrum

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. The Mujahedin-e Khalq in Iraq A Policy Conundrum Jeremiah Goulka, Lydia Hansell, Elizabeth Wilke, Judith Larson Sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense Approved for public release; distribution unlimited NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE The research described in this report was prepared for the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). -

The Peter and Katherine Tomassi Essay the Iranian Revolution

16 Salvatore • Causes & Effects: Global Financial Crisis The Peter and Katherine Tomassi Essay could potentially achieve gradually. Surprisingly household savings thE iranian rEvolution: aSSESSinG thE already seem to have begun rising in the past year. PowEr, inFluEnCE and SoCial PoSition In the present crisis atmosphere, many nations may over- oF ShiitE ulama in iran, 1890–1979 regulate and impose excessive restrictions on financial activities that would be detrimental to future growth. There is also the dan- ger that the large injection of liquidity in the United States and in José Ciro Martinez other advanced countries to jump-start their economies will lead to t was an oft-unrecognized assumption of modernization the- hyperinflation in two to three years’ time, which would then require ory, the dominant social science paradigm of the 1960s and a sharp tightening of monetary policy. I1970s, that the character and trajectory of historical change was both universal and unilinear. Drawing mainly on the work of ConCluSion Max Weber,1 scholars such as David Apter, Seymour Martin Lip- set, and Middle East expert Daniel Lerner argued that economic Eventually this crisis will end as all crises do. The important growth, capitalism, urbanization, and the impact of Western cul- question then becomes: will growth in advanced countries, espe- tural forms were essential factors for democratic development and cially in the United States, be rapid or slow? In short, will there be would result in the eradication of primitive or traditional forms growth or stagnation after recession? Of course, no one can know of societal organization and everyday life. -

Islam, Science and Government According to Iranian Thinkers 1Maryam Shamsaei Dr., Ph.D, 2Mohd Hazim Shah .Professor

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 2 Issue 1 ǁ January. 2013ǁ PP.64-74 Islam, Science and Government According To Iranian Thinkers 1Maryam Shamsaei Dr., Ph.D, 2Mohd Hazim Shah .Professor 1Dept of Islamic Education, Faculty of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. 2Dept of Science & Technology Studies Faculty of Science University of Malaya Kuala Lumpur 50603 ABSTRACT: Nothing troubled the people of the Islamic world at the beginning of the twenty-first century as much as the challenge of modernity did. It had occupied a central place in the cultural and sociopolitical agendas of intellectual and social movements, and state actors in the Islamic world and Iran since the 19th century. This study is a theoretical analysis of Iranian Muslim intellectuals’ encounter with Islam and modernity. The two main spheres of modernity which are examined are: i) the political arena and the government structure, and ii) science and technology. The goal of this dissertation is to examine and investigate the controversial ideas of five Iranian Muslim intellectuals, namely: Ali Shariati, Abdolkarim Soroush, Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Murteza Mutahhari, and Mehdi Golshani. Their ideas were then compared in order to identify the similarities and dissimilarities in their ideas on Islam and modernity. It is hoped that through this study, a contribution can be made to the current debate on Islam, science and politics, as well as creating an alternative Islamic perspective with regards to science, technology and a systematic government. This study is part of an accumulated effort towards the rejuvenation of the Islamic world in the modern era, including the field of science and technology. -

Adele K. Ferdows WOMEN and the ISLAMIC REVOLUTION

Int. J. Middle East Stud. 15 (1983), 283-298 Primed in the United States of America Adele K. Ferdows WOMEN AND THE ISLAMIC REVOLUTION INTRODUCTION Defining the role of women in Islamic society has been an issue for debate in post-revolutionary Iran, particularly in light of recent rulings affecting women. This is not merely a theoretical debate but a crisis situation where some women who participated in the revolution alongside men now find themselves in a peculiarly difficult position in relation to society and the current government. Ali Shariati (d. 1977), through his published works and transcribed lectures during the 1960s and 1970s, has had a tremendous impact on the direction of this debate. Completely rejecting the role of women in both western and traditional societies, Shariati offers a third alternative: the figure of Fatima, daughter of the Prophet Mohammad and wife of Ali, the first Imam of the Shicis as the personification of women's role. After the 1979 revolution in Iran, partly owing to the impact of Shariati's ideas and partly because of women's active participation in the course of the revolution and their resulting politicization, scattered essays were published dealing with questions relating to the position of women in Islamic society. As the revolutionary forces took firm hold of governmental machinery, rulings and decrees directed specifically at women were issued by various government officials, widening even further the scope of the debate on the role of women in the Muslin Iranian society. SHARIATI'S APPROACH TO THE ANALYSIS OF WOMEN'S POSITION IN A MUSLIM SOCIETY Shariati approaches the understanding of women's role from two angles.