Adele K. Ferdows WOMEN and the ISLAMIC REVOLUTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion and Politics

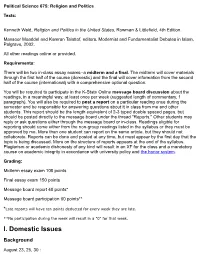

Political Science 675: Religion and Politics Texts: Kenneth Wald, Religion and Politics in the United States, Rowman & Littlefield, 4th Edition. Mansoor Moaddel and Kamran Talattof, editors, Modernist and Fundamentalist Debates in Islam, Palgrave, 2002. All other readings online or provided. Requirements: There will be two in-class essay exams--a midterm and a final. The midterm will cover materials through the first half of the course (domestic) and the final will cover information from the second half of the course (international) with a comprehensive optional question. You will be required to participate in the K-State Online message board discussion about the readings, in a meaningful way, at least once per week (suggested length of commentary, 1 paragraph). You will also be required to post a report on a particular reading once during the semester and be responsible for answering questions about it in class from me and other students. This report should be the length equivalent of 2-3 typed double spaced pages, but should be posted directly to the message board under the thread "Reports." Other students may reply or ask questions either through the message board or in-class. Readings eligible for reporting should come either from the non-group readings listed in the syllabus or they must be approved by me. More than one student can report on the same article, but they should not collaborate. Reports can be done and posted at any time, but must appear by the first day that the topic is being discussed. More on the structure of reports appears at the end of the syllabus. -

Not for Distribution

6 The decline of the legitimate monopoly of violence and the return of non-state warriors Cihan Tuğal Introduction For the last few decades, political sociology has focused on state-making. We are therefore quite ill equipped to understand the recent rise of non-state violence throughout the world. Even if states still seem to perform more violence than non- state actors, the latter’s actions have come to significantly transform relationships between citizens and states. Existing frameworks predispose scholars to treat non-state violence too as an instrument of state-building. However, we need to consider whether non-state violence serves other purposes as well. This chapter will first point out how the post-9/11 world problematises one of sociology’s major assumptions (the state’s monopolisation of legitimate violence). It will then trace the social prehistory of non-state political violence to highlight continui- ties with today’s intensifying religious violence. It will finally emphasise that the seemingly inevitable rise of non-state violence is inextricably tangled with the emergence of the subcontracting state. Neo-liberalisation aggravates the practico- ethical difficulties secular revolutionaries and religious radicals face (which I call ‘the Fanonite dilemma’ and ‘the Qutbi dilemma’). The monopolisation of violence: social implications War-making, military apparatuses and international military rivalry figure prominently in today’s political sociology. This came about as a reaction to the sociology and political science of the postwar era: for quite different rea- sons, both tended to ignore the influence of militaries and violence on domestic social structure. Political science unduly focused on the former and sociology on the latter, whereas (according to the new political sociology) international violence and domestic social structure are tightly linked (Mann 1986; Skocpol 1979; Tilly 1992). -

Revolution in Bad Times

asef bayat REVOLUTION IN BAD TIMES ack in 2011, the Arab uprisings were celebrated as world- changing events that would re-define the spirit of our political times. The astonishing spread of these mass uprisings, fol- lowed soon after by the Occupy protests, left observers in Blittle doubt that they were witnessing an unprecedented phenomenon— ‘something totally new’, ‘open-ended’, a ‘movement without a name’; revolutions that heralded a novel path to emancipation. According to Alain Badiou, Tahrir Square and all the activities which took place there—fighting, barricading, camping, debating, cooking and caring for the wounded—constituted the ‘communism of movement’; posited as an alternative to the conventional liberal-democratic or authoritar- ian state, this was a universal concept that heralded a new way of doing politics—a true revolution. For Slavoj Žižek, only these ‘totally new’ political happenings, without hegemonic organizations, charismatic leaderships or party apparatuses, could create what he called the ‘magic of Tahrir’. For Hardt and Negri, the Arab Spring, Europe’s indignado protests and Occupy Wall Street expressed the longing of the multitude for a ‘real democracy’, a different kind of polity that might supplant the hopeless liberal variety worn threadbare by corporate capitalism. These movements, in sum, represented the ‘new global revolutions’.1 ‘New’, certainly; but what does this ‘newness’ tell us about the nature of these political upheavals? What value does it attribute to them? In fact, just as these confident appraisals were being circulated in the us and Europe, the Arab protagonists themselves were anguishing about the fate of their ‘revolutions’, lamenting the dangers of conservative restora- tion or hijacking by free-riders. -

Islam, Science and Government According to Iranian Thinkers 1Maryam Shamsaei Dr., Ph.D, 2Mohd Hazim Shah .Professor

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 2 Issue 1 ǁ January. 2013ǁ PP.64-74 Islam, Science and Government According To Iranian Thinkers 1Maryam Shamsaei Dr., Ph.D, 2Mohd Hazim Shah .Professor 1Dept of Islamic Education, Faculty of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. 2Dept of Science & Technology Studies Faculty of Science University of Malaya Kuala Lumpur 50603 ABSTRACT: Nothing troubled the people of the Islamic world at the beginning of the twenty-first century as much as the challenge of modernity did. It had occupied a central place in the cultural and sociopolitical agendas of intellectual and social movements, and state actors in the Islamic world and Iran since the 19th century. This study is a theoretical analysis of Iranian Muslim intellectuals’ encounter with Islam and modernity. The two main spheres of modernity which are examined are: i) the political arena and the government structure, and ii) science and technology. The goal of this dissertation is to examine and investigate the controversial ideas of five Iranian Muslim intellectuals, namely: Ali Shariati, Abdolkarim Soroush, Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Murteza Mutahhari, and Mehdi Golshani. Their ideas were then compared in order to identify the similarities and dissimilarities in their ideas on Islam and modernity. It is hoped that through this study, a contribution can be made to the current debate on Islam, science and politics, as well as creating an alternative Islamic perspective with regards to science, technology and a systematic government. This study is part of an accumulated effort towards the rejuvenation of the Islamic world in the modern era, including the field of science and technology. -

ISLAM AS an IDEAL MODERN SOCIAL SYSTEM (A Study of Ali Shariati’S Thought)

ARTIKEL ISLAM AS AN IDEAL MODERN SOCIAL SYSTEM (A Study of Ali Shariati’s Thought) Abstract This article reexamines Ali Shariati’s thought in formatting ,slamic social order. The discussion is important in lighting discourses on Islamic society which is now being evaporated but has new challenges in new circumstances and time of the Muslim community. By taNing the texts translated from Shariati’s EooNs and articles this study descriEes and analyzes the format of Shariati’s thought, what are being rejected by him, and what is the formulation being proposed by him in order to develop Islamic community. Finally, it also contextualizes Shariati’s thought with what Eeing happened in its time in direction to project to our time. Keywords: Shariati, Islamic Thought, Islamic Resurgence. M. Taufiq Rahman A. Introduction [email protected] The coming back of the West to be politically involved in Muslim Dosen FISIP UIN Sunan Gunung Djati regions such as Tunisia, Syria, Iraq, Bandung Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Pakistan has made the pillars of the civil establishment in such Muslim countries shaken. It remains us of the emergences of freedom movements in the early modern time in the Muslim countries which had achieved their freedom life out of the Western occupation. At that time Muslim intellectuals dig their reference to Islam concerning the statecraft. Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Muhammad Abduh, Muhammad Iqbal, and Muhammad Asad were the pioneers of this intellectual movement. Followed by Sayyid Qutb and Abu al- ‘Ala al-Maududi, and Ali Shariati among others, this enterprise was strengthened. To this, reopening our intellectual storage of the reconstruction of Islamic order in the modern world is extremely needed today, that is, the time of restructuring Islam as the ideology of the Muslim community (ummah). -

Shia Islam and the Iranian Revolution Written by Nathan Olsen

Revolutionary Religion: Shia Islam and the Iranian Revolution Written by Nathan Olsen This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Revolutionary Religion: Shia Islam and the Iranian Revolution https://www.e-ir.info/2019/09/03/revolutionary-religion-shia-islam-and-the-iranian-revolution/ NATHAN OLSEN, SEP 3 2019 The Iranian revolution of 1979 saw a mass movement of diverse interests and political groups within Iranian society come together to overthrow the Shah. This would eventually lead to the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran in April 1979 and the creation of a new constitution that December. However, the movement to depose the Shah and the movement driving the construction of a new political system in Iran constituted two separate movements. As Moghadam (2002:1137) argues, ‘Iran had two revolutions…the populist revolution…[and] the Islamic revolution’. In this essay, I will focus on the ‘populist revolution’ and the extent to which it can be labelled Islamic. This focus on the first revolution is important, as its nature is contested (Kurzman, 1995; Sohrabi, 2018). In contrast, the second revolution was undeniably Islamic: the successful referendum on the establishment of the Islamic Republic, the creation of an Islamic constitution and the enshrinement of Ayatollah Khomeini as Supreme Leader of Iran all support this notion. Thus, my essay will consider to what extent we can label the ‘populist revolution’ as Islamic. It will be argued that it is appropriate to use this label, as the revolution utilised the narrative and organisational structure of Shi’a Islam to build a mass movement powerful enough to overthrow the Shah (Nasr, 2007; Richard, 1995; Roy, 1994). -

Dr. Ali Shariati

Hajj (The Pilgrimage ) Dr. Ali Shariati Translated by: Ali A. Behzadnia, M.D. & Najla Denny Prepared by the Evecina Cultural & Education Foundation (ECEF) P.O Box 11402 - Costa Mesa, CA 92627 Copyrights Preserved Published by Jubilee Press Hajj Preface by the Author As a person who is "knowledgeable about religion" and whose field of study is "the history of religions", I reached the following conclusions as a result of my study and research of the historical evolution of each faith whereby I compared what the faiths were in the past and what they are now as well as a comparison in the differences between the "truth" and the "reality" of the faiths. My conclusion is not based on personal religious feelings nor prejudices: If we study and evaluate the effectiveness of each religion in terms of the happiness and evolution of mankind, we will discover that there is no prophecy which is as advanced, powerful, and conscious as the prophecy of Mohammad (PBUH) (i.e. Islam and its role in man's social progress, self-consciousness, movement, responsibility, human ambition and struggle for justice; Islam's realism and naturalness, creativity, adaptability with scientific and financial progress and orientation toward civilization and the community). Contemporaneously, we will discover that there is no prophecy which has deteriorated and been transformed into a completely different representation as much as the prophecy of Mohammad (PBUH)! It seems that some power composed of all physical facilities as well as knowledgeable advisors, openly or secretly has hired a group of the most educated and intelligent philosophers of history, social scientists, sociologists, social psychologists, politicians, human scientists, theologists. -

The Methodology of Ali Shari'ati: a Comparison with Durkheim's and Weber's Sociology of Religion

IIUM Journal of Human Sciences Vol. 1. No. 2, 2019, 30-42 ISSN 2682-8731 (Online) The Methodology of Ali Shari’ati: A Comparison with Durkheim’s and Weber’s Sociology of Religion Younus Ahmed Mushtaq Ahmed1 and Zulqernain Haider Subhani International Islamic University Malaysia ABSTRACT Ali Shari‟ati was an ideologue par excellence, who through his writings and fiery speeches, was able to attract the young intelligentsia of Iran and prepare them for the cataclysmic movement that took place in 1979. The methodology adopted by Ali Shari‟ati in his study of religion was different from two classical sociologists. The objective of this paper is to highlight how Ali Shari‟ati differed in his sociology of religion from sociologists, such as Emilé Durkheim and Max Weber. Through thematic content analysis, the works of the authors were reviewed to understand their methodology. The findings of this paper outline the methodology adopted by Ali Shari‟ati, which was different, both, in its approach and the tools used to analyze religion. Though there was a shift in methodology when compared to classical sociologists, this paper agrees that the methodology of Ali Shari‟ati was the best suited to study a deeply religious Asian society such as Iran. Keywords: Ali Shari‟ati, Methodology, Sociology of religion, Muslim Thinker, Emilé Durkheim, and Max Weber. INTRODUCTION Ali Shari‟ati, a prominent Iranian intellectual, is considered by many as the „ideological father of the Iranian revolution who through his writings and fiery speeches was able to reach and communicate with the Iranian youths in way that both the religious class and the secular government of the Mohammed Reza Shah were never able to communicate (Abedi, 1986; Dabashi, 1993; Rahnema, 2000; Sachedina, 1983). -

Alchemist of Revolution: Ali Shariati's Political Thought in International

Spectrum Journal of Global Studies Vol. 6, No. 1 The -Alchemist of Revolution: Ali Shariati’s Political Thought in International Context Kamran Matin ABSTRACT This article challenges essentialist conceptions of “political Islam” as the ideology of an internally generated rejection of modernity through reconceptualising Ali Shariati’s idea of “revolutionary Islam” as an internationally constituted mediation of modernity. It argues that “the international” was central to Shariati’s artful combination of western and Shi’i-Islamic ideas and concepts. This hybrid character, the article argues, underlay the remarkable political appeal of Shariati’s discourse of revolutionary Islam to broad sections of the population whose subjectivity had, in turn, been re-shaped by the ideological ramifications of the formation of the novel phenomenon of “the citizen-subject”, a hybrid sociological form produced by Iran’s experience of modern uneven and combined development. Keywords: The Citizen-Subject, International Relations, Iran, Islam, Shariati, Substitution, Uneven and Combined Development My Lord … tell my people that the only path towards you passes through the earth, and show me a shortcut. Ali Shariati If there are obstacles the shortest linebetween two points may well be acrooked line. Bertolt Brecht Introduction Ali Shariati is widely regarded as the ideological architect of the Iranian Revolution. 1 His portraits were often carried side by side with those of the revolution’s charismatic leader Ayatollah Khomeini during anti-Shah mass demonstrations. Shariati’s ideas have also been highly influential in post- revolutionary period. A number of important political organizations active in post- revolutionary Iran drew directly on Shariati’s political ideas. -

Theology of Revolution: in Ali Shari'ati and Walter Benjamin's Political

religions Article Theology of Revolution: In Ali Shari’ati and Walter Benjamin’s Political Thought Mina Khanlarzadeh MESAAS, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, USA; [email protected] Received: 4 August 2020; Accepted: 23 September 2020; Published: 1 October 2020 Abstract: In this paper, I offer a comparative analysis of the political thoughts of twentieth century Iranian revolutionary thinker and sociologist Ali Shari’ati (1933–1977) and German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892–1940). Despite their conspicuously independent historical-theoretical trajectories, both Shari’ati and Benjamin engaged with theology and Marxism to create theological–political conceptions of the revolution of the oppressed. Shari’ati re-interpreted and re-animated Shia history from the angle of contemporary concerns to theorize a revolution against all forms of domination. In comparison, Benjamin fused Marxism with Jewish theology in his call to seize the possibilities of past failed revolutions in the present. Both Shari’ati and Benjamin conceptualized an active messianism led by each generation, eliminating the wait for the return of a messiah. As a result, each present moment takes on a messianic potential; the present plays an essential role to both thinkers. Past was also essential to both, because theology (through remembrance) had made the past sufferings incomplete to them. Both thinkers viewed past sufferings as an integral part of present struggles for justice in the form of remembrance (or yad¯ or zekr for Shari’ati, and Zekher for Benjamin). I explore the ways Shari’ati and Benjamin theorized the role of the past in the present, remembrance, and messianism to create a dialectical relation between theology and Marxism to reciprocally transform and compliment both of them. -

Ali Shariati's View of Islamic Modernity

Ali Shariati’s View of Islamic Modernity Malik Mohammad Tariq ∗ Abstract Influenced by Iqbal’s Ideology and Philosophy Dr. Ali Shariati (1933- 77) Philosopher-activist, Revolutionary thinker, is one of the most outstanding modern interpreters of Islamic thought. He awakened a new interest and confidence in Islam. He was neither a reactionary fanatic who opposed anything that was new without any knowledge nor he was westernized intellectual who imitated the West without independent judgment. Ali Shariati is one of the most brilliant Islamic thinkers, having studied Islam and contemporary Western thoughts and presented an Islamic critique, which remains of tremendous value to young Muslim generations who are swept away from Islam by the glamour of Western capitalism or Marxism. Ali Shariati is extensively recognized as the intellectual ideologue of the Iranian revolution. Shariati presents a very complex and diverse mix of ideas: radical Islamic fundamentalism, traditional Muslim thought, a mystical Sufi modes, dialectical Marxism, Western existentialism, and anti- imperialism. In the present study his views are presented which point out the causes of backwardness, deterioration, stagnation and called for launching of religious revival, that is, awaking them of slumber and making society going back to life and movement and fighting suppressions. He presents the way of enlightenment to the society that would be able to transmit his understanding outside the narrow and limited group of his generation. Keywords : Ali Shariati, Islam, Islamic Modernity, Renaissance Ali Shariati, contends that the two types of Islam, that had confronted one another in Islamic history were ‘the degenerate and narcotizing religion’ and ‘the progressive and awakening religion’. -

Islam and Democracy

TEMA A DEBATE: Islam y democracia ¿son compatibles? HISTORIA DEL DERECHO ESPAÑOL GRUPO DADE (51) Profa. Mª Magdalena Martínez Almira Islam and Democracy By John L. Esposito and John O. Voll http://www.neh.gov/news/humanities/2001-11/islam.html The relationship between Islam and democracy in the contemporary world is complex. The Muslim world is not ideologically monolithic. It presents a broad spectrum of perspectives ranging from the extremes of those who deny a connection between Islam and democracy to those who argue that Islam requires a democratic system. In between the extremes, in a number of countries where Muslims are a majority, many Muslims believe that Islam is a support for democracy even though their particular political system is not explicitly defined as Islamic. Throughout the Muslim world in the twentieth century, many groups that identify themselves explicitly as Islamic attempted to participate directly in the democratic processes as regimes were overthrown in Eastern Europe, Africa, and elsewhere. In Iran such groups controlled and defined the system as a whole; in other areas, the explicitly Islamic groups were participating in systems that were more secular in structure. The participation of self-identified Islamically oriented groups in elections, and in democratic processes in general, aroused considerable controversy. People who believe that secular approaches and a separation of religion and politics are an essential part of democracy argue that Islamist groups only advocate democracy as a tactic to gain political power. They say Islamist groups support “one man, one vote, one time.” In Algeria and Turkey, following electoral successes by parties thought to be religiously threatening to the existing political regimes, the Islamic political parties were restricted legally or suppressed.