Alask4 Gold Dredging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nome River Water Control Structures

BLM LIBRARY 88049206 Department of the Interior BLM-Alaska Open File Report 62 Bureau of Land Management BLM/AK/ST-97/003+81 00+020 April 1997 Alaska State Office 222 West 7th, #13 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 Nome River Water Control Structures Howard L. Smith JK 870 .L3 06 no. 62 ^&&£ *>v^ fe Nome River Water Control Structures Howard L. Smith U.S. Department of the Interior of Bureau Land Management 0pen Fi)e Report 62 Alaska State Office -| ^pr il 997 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 Author Howard Smith is an archaeologist with the Northwest Management Team, Northern District, Bureau of Land Management, Fairbanks, Alaska. Open File Reports Open File Reports identify the results of inventories or other investigations that are made available to the public outside the formal BLM-Alaska technical publication series. These reports can include preliminary or incomplete data and are not published and distributed in quantity. The reports are available at BLM offices in Alaska, the USDI Resources Library in Anchorage, various libraries of the University of Alaska, and other selected locations. Copies are also available for inspection at the USDI Natural Resources Library in Washington, D.C. and at the BLM Service Center Library in Denver. Cover Photo: Headgate of the Miocene Ditch on the Nome River, Alaska. Photo by Howard L Smith Table of Contents Abstract 1 Background 1 Discovery of Gold 1 Events in 1899 2 Events in 1900 4 Events after 1900 5 Water Control Structures 6 The Miocene Ditch 7 The Seward Ditch 17 The Pioneer Ditch 18 The Campion Ditch 19 The -

Buried Treasures Volume Xvi No

BURIED TREASURES VOLUME XVI NO . 4 OCTOBER 1984 AND .• 1 · ~ (/) ~ + c::> ' ...--...._ a:- ("') C) A-. _.j ,..,., .- u- ....... ~ } . I Pultllahed tty CENTRAL FLORIDA GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY ORLANDO, F~ORIDA TABLE OF CONTENTS President's Message . .. 70 Rex Beach--Non-Conformist. 71 Pineys . .. ' 73 Eber Bradley (1761-1841) and Some Relatives. 74 :Genealogical Abstract of a Standard History of Freemasonry in the State of New York, Vol. II. ... 76 James Dallis Ti l lis 1873-1943 ..... 78 .. Partial 1840 Census of Pike County, IL 80 Causes of Death--Missouri Style! . 81 Geneva Cemetery , Seminole County , FL • • 82 The History of the First Baptist Church of Conway. 86 Queries .. .. 89 Surname Index .. 91 Geographical Index • 92 I . FALL CONTRIBUTORS Carrie Hull Boswell Alberta Louise Tillis Cobia Opal Tillis Flynn . \ ~ . Betty Brinsfield Hughson Verna Hartman McDowell Allen Taylor Jean Geisler Vogelius Andrea Hickman White Grace L. Young BURIED TREASURES - i - V16#4-0ct 1984 p RE SI v E NTIs M Ess A G E Oc.tobe.Jt 7984 Veak Membe.Jt~ and F~~e~, I am hono~ed to be yo~ new P~e~~dent and ~halt endeavok to ~eAve you to the be~t o6 my ab~l~ty 6o~ the next yeak. Yo~ ~up po~t and loyalty w~ll help the Soc.~ety to g~ow and to bec.ome mo~e help6ul to eve.Jtyone. Yo~ new Boakd o6 V~ec.tM~ hM ~takted to make plaM 6M the c.om~ng yeak, but we need help 6~om all o6 you. A~ you know, wokk~ng togethe.Jt w~tl make ~ g~ow togethe.Jt. -

Iditarod National Historic Trail I Historic Overview — Robert King

Iditarod National Historic Trail i Historic Overview — Robert King Introduction: Today’s Iditarod Trail, a symbol of frontier travel and once an important artery of Alaska’s winter commerce, served a string of mining camps, trading posts, and other settlements founded between 1880 and 1920, during Alaska’s Gold Rush Era. Alaska’s gold rushes were an extension of the American mining frontier that dates from colonial America and moved west to California with the gold discovery there in 1848. In each new territory, gold strikes had caused a surge in population, the establishment of a territorial government, and the development of a transportation system linking the goldfields with the rest of the nation. Alaska, too, followed through these same general stages. With the increase in gold production particularly in the later 1890s and early 1900s, the non-Native population boomed from 430 people in 1880 to some 36,400 in 1910. In 1912, President Taft signed the act creating the Territory of Alaska. At that time, the region’s 1 Iditarod National Historic Trail: Historic Overview transportation systems included a mixture of steamship and steamboat lines, railroads, wagon roads, and various cross-country trail including ones designed principally for winter time dogsled travel. Of the latter, the longest ran from Seward to Nome, and came to be called the Iditarod Trail. The Iditarod Trail today: The Iditarod trail, first commonly referred to as the Seward to Nome trail, was developed starting in 1908 in response to gold rush era needs. While marked off by an official government survey, in many places it followed preexisting Native trails of the Tanaina and Ingalik Indians in the Interior of Alaska. -

Alexander Mckenzie, Boss of North Dakota 1883-1906 Kenneth J

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 6-1-1949 Alexander McKenzie, Boss of North Dakota 1883-1906 Kenneth J. Carey Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Carey, Kenneth J., "Alexander McKenzie, Boss of North Dakota 1883-1906" (1949). Theses and Dissertations. 463. https://commons.und.edu/theses/463 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alexander licKenzie, Boss of North Dakota 188.?-1906 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Department of the University of North Dakota by Kenneth J. Carey u In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts June, 1949 < £ 3 Ti ls thesis, offered by Kenneth J. C*rey, as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art at the University of North Dakota, is hereby approved by the committee under whom the work has been done. vTsIon 3c N/V9 3c A 0 KN 0 WLED G3K 3 NT 3 The author wishes to extend his appreciation to the people who have made this thesis possible. Dr. Elwvn B. Robinson, who took purest interest in, and who worked diligently witn o.iie author in preparing this work, deserves soecial acknowledgment. Dr. Feli-v J. Vondracek -ave inspiration to the author in iie interest in historical study. -

Steve Mccutcheon Collection, B1990.014

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Archivist TITLE: Steve McCutcheon Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1990.014 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1890-1990 Extent: approximately 180 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): Steve McCutcheon, P.S. Hunt, Sydney Laurence, Lomen Brothers, Don C. Knudsen, Dolores Roguszka, Phyllis Mithassel, Alyeska Pipeline Services Co., Frank Flavin, Jim Cacia, Randy Smith, Don Horter Administrative/Biographical History: Stephen Douglas McCutcheon was born in the small town of Cordova, AK, in 1911, just three years after the first city lots were sold at auction. In 1915, the family relocated to Anchorage, which was then just a tent city thrown up to house workers on the Alaska Railroad. McCutcheon began taking photographs as a young boy, but it wasn’t until he found himself in the small town of Curry, AK, working as a night roundhouse foreman for the railroad that he set out to teach himself the art and science of photography. As a Deputy U.S. Marshall in Valdez in 1940-1941, McCutcheon honed his skills as an evidential photographer; as assistant commissioner in the state’s new Dept. of Labor, McCutcheon documented the cannery industry in Unalaska. From 1942 to 1944, he worked as district manager for the federal Office of Price Administration in Fairbanks, taking photographs of trading stations, communities and residents of northern Alaska; he sent an album of these photos to Washington, D.C., “to show them,” he said, “that things that applied in the South 48 didn’t necessarily apply to Alaska.” 1 1 Emanuel, Richard P. -

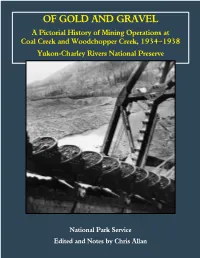

Of Gold and Gravel: a Pictorial History of Mining Operations at Coal Creek

OF GOLD AND GRAVEL A Pictorial History of Mining Operations at Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, 1934–1938 Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Park Service Edited and Notes by Chris Allan OF GOLD AND GRAVEL A Pictorial History of Mining Operations at Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, 1934–1938 Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve Edited and Notes by Chris Allan 2021 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Lynn Johnson, the granddaughter of Walter Johnson who designed the Coal Creek and Woodchooper Creek dredges; Rachel Cohen of the Alaska and Polar Regions Collections & Archives; and Jeff Rasic, Adam Freeburg, Kris Fister, Brian Renninger, and Lynn Horvath who all helped with editing and photograph selection. For additional copies contact: Chris Allan National Park Service Fairbanks Administrative Center 4175 Geist Road Fairbanks, Alaska 99709 Printed in Fairbanks, Alaska Front Cover: View from the pilot house of the Coal Creek gold dredge showing the bucket line carrying gravel to be processed inside the machine. The bucket line could dig up to twenty-two feet below the surface. University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska & Polar Regions Collections and Archives, Stanton Patty Family Papers. Title Page Inset: A stock certificate for Gold Placers, Inc. signed by General Manager Ernest N. Patty, November 16, 1935. University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska & Polar Regions Collections and Archives, Stanton Patty Family Papers. Back Cover: Left to right: The mail carrier Adolph “Ed” Biederman, his son Charlie, daughter Doris, the trapper and miner George Beck, Ed’s son Horace, and Jack Welch, the proprietor of Woodchopper Roadhouse. The group is at Slaven’s Roadhouse on the banks of the Yukon River posing with a mammoth tusk recovered from a placer mining tunnel. -

Mines of El Dorado County

by Doug Noble © 2002 Definitions Of Mining Terms:.........................................3 Burt Valley Mine............................................................13 Adams Gulch Mine........................................................4 Butler Pit........................................................................13 Agara Mine ...................................................................4 Calaveras Mine.............................................................13 Alabaster Cave Mine ....................................................4 Caledonia Mine..............................................................13 Alderson Mine...............................................................4 California-Bangor Slate Company Mine ........................13 Alhambra Mine..............................................................4 California Consolidated (Ibid, Tapioca) Mine.................13 Allen Dredge.................................................................5 California Jack Mine......................................................13 Alveoro Mine.................................................................5 California Slate Quarry .................................................14 Amelia Mine...................................................................5 Camelback (Voss) Mine................................................14 Argonaut Mine ..............................................................5 Carrie Hale Mine............................................................14 Badger Hill Mine -

Environmental Assessment Frostfire Prescribed Burn BLM Northern

Environmental Assessment of the Frostfire Prescribed Burn BLM Northern Field Office 1150 University Avenue Fairbanks, AK. 99709 BLM Alaska Fire Service P.O. Box 35005 Ft. Wainwright, AK. 99703 No. AK-AFS-EA-99-AA03 April 5, 1999 2 I. Introduction The Bureau of Land Management-Alaska Fire Service (BLM-AFS) proposes to assist in conducting a prescribed burn to meet objectives of the Frostfire Project funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). BLM-AFS has prepared a Burn Plan (Wilmore, et. al., 1998) (See Attachment A) for approval by the University of Alaska, Fairbanks (UAF) and the State of Alaska Department of Natural Resources (ADNR). BLM-AFS would provide the Incident Commander/Burn Boss and other key positions for burn operation, and provide all command and safety functions during the operation. The research watershed selected for the prescribed burn is the C-4 subwatershed of the Caribou- Poker Creeks Research Watershed (CPCRW) (See Map A) which is part of the Bonanza Creek Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) Site (See Map B) operated by UAF. BLM-AFS would prepare the C-4 watershed for burning, including developing and constructing helispots, fuel breaks and access trails. BLM-AFS would also provide personnel and equipment during preburn, burn, and mopup operations. The Frostfire Project is a cooperative effort between UAF, the USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station (PNW), ADNR, the Canadian Forestry Service, and BLM-AFS. A Memorandum of Understanding (# PNW 98-5124-2-MOU) was signed by all parties in May and June, 1998 to formalize Frostfire cooperative efforts. The Frostfire Project would be a continuation of international fire research activities under the International Boreal Forest Research Association Stand Replacement Fire Working Group, and as part of the LTER program. -

Commissioner of Mines for The

TERRITORY OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF MINES Report of the Commissioner of Mines for the EPENNPUM ENDED DECEMBER 31, 1954 DEPARTMENT OF MINES STAFF ON DECEMBER. 31, 1954 Phil R. Holdsworth, Commissioner of Mines, Box 1391, Juneau January 10, 1955 James A. Williams, Associate Mining Engineer, Box 1391, Juneau Honorable B. Frank Heintzleman Tdartin W. Jasper, Associate Mining Engineer, Box 2139, Anchorage Governor of Alaska Juneau. Alaska Wiley D. Robinson, Associate Coal Mining Engineer, Box 2139, Anchorage Sir : Robert M. Saunders, Associate Mining Engineer, Box C, College I I have the honor to submit to you, and through you Arthur E. Glover, Assayer-Engineer, Box 1408, Ketchikan to the Twenty-second Session of the Territorial kegisla- I ture, in accordance with Section 47-3-1319, ACLA, 1949, Peter 0. Sandvik, Assayer-Engineer, Box 657, Norne the report of the Commissioner of Mines for the bien- William F. Attwood, Assayer-Engineer, Box @, College nium ended December 31, 1954. RoyPe C. Rowe, Assayes, Box 2139, Anchorage Respectfully submitted, Cathryn Mack, Administrative Assistant, Box 1391, Juneau PHIL R. HOLDSWORTH Jean Crosby, Stenographer-Clerk, Box 1391, Juneau Commissioner of Mines CONTENTS Page Letter of Transmittal .................................................................................. 3 The I>epartment of Mines ............................................................................. 7 Atlministrative and General Information ........................................ 7 Cooperation with Federal Agencies ................................................... -

GULDEN-DISSERTATION-2021.Pdf (2.359Mb)

A Stage Full of Trees and Sky: Analyzing Representations of Nature on the New York Stage, 1905 – 2012 by Leslie S. Gulden, M.F.A. A Dissertation In Fine Arts Major in Theatre, Minor in English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. Dorothy Chansky Chair of Committee Dr. Sarah Johnson Andrea Bilkey Dr. Jorgelina Orfila Dr. Michael Borshuk Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leslie S. Gulden Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to my Dissertation Committee Chair and mentor, Dr. Dorothy Chansky, whose encouragement, guidance, and support has been invaluable. I would also like to thank all my Dissertation Committee Members: Dr. Sarah Johnson, Andrea Bilkey, Dr. Jorgelina Orfila, and Dr. Michael Borshuk. This dissertation would not have been possible without the cheerleading and assistance of my colleague at York College of PA, Kim Fahle Peck, who served as an early draft reader and advisor. I wish to acknowledge the love and support of my partner, Wesley Hannon, who encouraged me at every step in the process. I would like to dedicate this dissertation in loving memory of my mother, Evelyn Novinger Gulden, whose last Christmas gift to me of a massive dictionary has been a constant reminder that she helped me start this journey and was my angel at every step along the way. Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………ii ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………..………………...iv LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………..v I. -

{PDF EPUB} the Books of James C. Patch the Barrier by Gary D

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Books of James C. Patch The Barrier by Gary D. Henry The Real Winston Churchill. Winston Churchill was a crypto-Jew who sold out his country to advance the Rothschilds' program of world domination. The Masonic Jewish central bankers contrive wars for profit, to kill patriots and to degrade and enslave humanity. (Winston Churchill, Illuminati--Originally posted in Aug. 2005) By Henry Makow, Ph.D. After the first Nazi air raid on London Sept. 7, 1940 which killed 306 people, Winston Churchill remarked, "They cheered me as if I'd given them victory, instead of getting their houses bombed to bits ." (416) Churchill is telling the truth. Unknown to Londoners, he had rejected Hitler's proposal to spare civilian targets. Quite the opposite, he goaded Hitler into bombing London by hitting Berlin and other civilian targets first. Churchill told his Air Marshall: "Never mistreat an enemy by halves" and instructed his cabinet, "bombing of military objectives, increasingly widely interpreted, seems our best road home at present." He blocked the Red Cross from monitoring civilian casualties. (440) Before the end of Sept. 1940, 7,000 Londoners including 700 children lay dead. By the end of the war, more than 60,000 British civilians and 650,000 German civilians died from "strategic" bombing. In 1940, Churchill had to divert attacks from RAF airfields but he also wanted to start the bloodletting. A year had passed with little action. It was being called the "phoney war." Hitler was making generous peace offers that prominent Englishmen wanted to accept. -

An Archaeologist's Guide to Mining Terminology

AUSTRALASIAN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, I5, I997 An Archaeologist'sGuide to Mining Terminology Ited 5as NEVILLEA. RITCHIEAND RAY HOOKER ing Iter the The authors present a glossary of mining terminology commonly used in Australia and New Zealand. The npl definitions and useagescome from historical and contemporary sources and consideration is given to those most frequently encounteredby archaeologists. The terms relate to alluvial mining, hard rock mining, ore rlll9 processing,and coal mining. rng. the \on resultantmodified landforms and relicswhich arelikely to be rnd Thereare literally thousandsof scientificand technicalterms ,of which have been coined to describevarious aspects of the encounteredby or to be of relevanceto field archaeologists processing metalliferousand non-metallic ores. working in mining regionsparticularly in New Zealandbut 1,raS miningand of M. Manyterms have a wide varietyof acceptedmeanings, or their also in the wider Australasia.Significant examples, regional :of meaningshave changed over time. Otherterms which usedto variants,the dateof introductionof technologicalinnovations, trrng be widely used(e.g. those associated with sluice-mining)are and specificallyNew 7na\andusages are also noted.Related Ito seldom used today. The use of some terms is limited to terms and terms which are defined elsewherein the text are nial restrictedmining localities (often arising from Comish or printedin italics. other ethnic mining slang),or they are usedin a sensethat While many of the terms will be familiar to Australian differsfrom thenorm; for instance,Henderson noted a number ella archaeologists,the authorshave not specificallyexamined' v)7 of local variantswhile working in minesat Reeftonon the Australian historical mining literature nor attempted to WestCoast of New T.ealand.l nla.