Iditarod National Historic Trail I Historic Overview — Robert King

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OBSIDIAN: an INTERDISCIPLINARY Bffiliography

OBSIDIAN: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY BffiLIOGRAPHY Craig E. Skinner Kim J. Tremaine International Association for Obsidian Studies Occasional Paper No. 1 1993 \ \ Obsidian: An Interdisciplinary Bibliography by Craig E. Skinner Kim J. Tremaine • 1993 by Craig Skinner and Kim Tremaine International Association for Obsidian Studies Department of Anthropology San Jose State University San Jose, CA 95192-0113 International Association for Obsidian Studies Occasional Paper No. 1 1993 Magmas cooled to freezing temperature and crystallized to a solid have to lose heat of crystallization. A glass, since it never crystallizes to form a solid, never changes phase and never has to lose heat of crystallization. Obsidian, supercooled below the crystallization point, remained a liquid. Glasses form when some physical property of a lava restricts ion mobility enough to prevent them from binding together into an ordered crystalline pattern. Aa the viscosity ofthe lava increases, fewer particles arrive at positions of order until no particle arrangement occurs before solidification. In a glaas, the ions must remain randomly arranged; therefore, a magma forming a glass must be extremely viscous yet fluid enough to reach the surface. 1he modem rational explanation for obsidian petrogenesis (Bakken, 1977:88) Some people called a time at the flat named Tok'. They were going to hunt deer. They set snares on the runway at Blood Gap. Adder bad real obsidian. The others made their arrows out of just anything. They did not know about obsidian. When deer were caught in snares, Adder shot and ran as fast as he could to the deer, pulled out the obsidian and hid it in his quiver. -

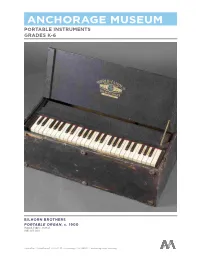

Anchorage Museum Portable Instruments Grades K-6

ANCHORAGE MUSEUM PORTABLE INSTRUMENTS GRADES K-6 BILHORN BROTHERS PORTABLE ORGAN, c. 1900 Wood, fabric, metal 1981.012.001 Education Department • 625 C St. Anchorage, AK 99501 • anchoragemuseum.org ACTIVITY AT A GLANCE Learn about portable instruments. Look closely at a portable reed organ from the late 1800s/early 1900s. Learn more about the organ and its owner. Listen to a video of a similar organ being played and learn more about how the instrument works. Brainstorm and sketch a portable instrument. Investigate other portable instruments in the Anchorage Museum collection. Create an instrument from recycled materials. PORTABLE ORGAN Begin by looking closely at the portable organ made by the Bilhorn Brothers company. If investigating the portable organ with another person, use the questions below to guide your discussions. If working alone, consider recording thoughts on paper: CLOSE-LOOKING Look closely, quietly at the organ for a few minutes. OBSERVE Share your observations about the organ or record your initial thoughts ASK • What do I notice about the organ? • What colors and materials does the artist use? • What sounds might the organ create? • What does it remind you of? • What more do you see? • What more can you find? DISCUSS USE 20 Questions Deck for more group discussion questions about the organ. LEARN MORE ABOUT THE MANUFACTURER Peter Philip Bilhorn was a well-known evangelist singer and composer who invented a portable reed organ to support his musical endeavors. With the support of his brother, George Bilhorn, he founded Bilhorn Brothers Organ Company of Chicago in 1885. Bilhorn Brothers manufactured portable reed organs, including the World-Famous Folding Organ in the Anchorage Museum collection. -

Arl,Samiwqw-.Jmrdnrt.±.-7-.Rrp:-Aenbzrrk-Rirn„ .Zwwr-Abtlr- I COLUMBIA COAST SERVICE 11111111EIL

n:pTzg,-Arl,samiwqw-.Jmrdnrt.±.-7-.rrp:-Aenbzrrk-rirn„_.zwwr-abtLr- i COLUMBIA COAST SERVICE 11111111EIL Palmers Lake, Atlin of British Columbia--to the left, Vancouver Island, FROMa thousand Vancouver, miles throughB. C., to an Skagway, entrancing Alaska, inland is taking its name from the intrepid explorer who sailed channel, winding between islands and the main- into the unknown waters of the Pacific and found land as through a fairyland. The journey is made in the mainland through an uncharted maze. To rea- the palatial yacht-like "Princess" steamers of the lize to the full the miracle of this thousand miles of Canadian Pacific Railway. navigation from Vancouver to Skagway, one should Nine days complete the journey into this land of stand for an hour or so looking forward, picking out romance and back, leaving the traveller at Van- what seems the channel the ship will take, and finding couver to start the journey to the East through the mag- out how invariably one's guess is wrong. For it is not nificent passes of the Canadian Pacific Rockies. Some, always the mainland which lies to the east. Often the moun- indeed, who make the Alaskan trip have come from the East, tains which tower up to the sky, almost from the very deck and already in the five hundred miles of railway travel through of the ship itself, are but islands; and other channels lie behind, the passes of the four great mountain ranges between Calgary with countless bays and straits and narrow gorges running miles and Vancouver have had a foretaste of the wonderful voyage up into the mainland, twisting, turning, creeping forward and through strait and fiord which awaits them between Vancouver doubling back, till they put to shame the most intricate maze and Skagway. -

Ditarod Trail International Sled Dog Race Official Rules 2015

DITAROD TRAIL INTERNATIONAL SLED DOG RACE OFFICIAL RULES 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS (note: the #’s refer to rule numbers.) Pre-Race Procedure & Administration 1 -- Musher Qualifications 2 -- Entries 3 -- Entry Fee 4 -- Substitutes 5 -- Race Start and Re-Start 6 -- Race Timing 7 -- Advertising, Public Relations & Publicity 8 -- Media 9 -- Awards Presentation 10 -- Scratched Mushers 11 -- Purse Musher Conduct and Competition 12 -- Checkpoints 13 -- Mandatory Stops 14 -- Bib 15 -- Sled 16 -- Mandatory Items 17 -- Dog Maximums and Minimums 18 -- Unmanageable Teams 19 -- Driverless Team 20 -- Teams Tied Together 21 -- Motorized Vehicles 22 -- Sportsmanship 23 -- Good Samaritan Rule 24 -- Interference 25 -- Tethering 26 -- Passing 27 -- Parking 28 -- Accommodations 2015 Race Rules 1 of 15 29 -- Litter 30 -- Use of Drugs & Alcohol 31 -- Outside Assistance 32 -- No Man’s Land 33 -- One Musher per Team 34 -- Killing of Game Animals 35 -- Electronic Devices 36 -- Competitiveness Veterinary Issues & Dog Care 37 -- Dog Care 38 -- Equipment & Team Configuration 39 -- Drug Use 40 -- Pre-Race Veterinary Exam 41 -- Jurisdiction & Care 42 -- Expired Dogs 43 -- Dog Description 44 -- Dog Tags 45 -- Dropped Dogs 46 -- Hauling Dogs Food Drops & Logistics 47 -- Shipping of Food & Gear 48 -- Shipping Amounts Officials, Penalties & Appeals 49 -- Race Officials 50 -- Protests 51 -- Penalties 52 -- Appeals OFFICIAL 2015 RULES Policy Preamble --The Iditarod Trail International Sled Dog Race shall be a race for dog mushers meeting the entry qualifications as set forth by the Board of Directors of the Iditarod Trail Committee, Inc. Recognizing the aptitude and experience necessary and the varying degrees of monetary support and residence locations of mushers, with due regard to the safety of mushers, the humane care and treatment of dogs and the orderly conduct of the race, the Trail Committee shall encourage and maintain the philosophy that the race be constructed to permit as many qualified mushers as possible who wish to enter and contest the Race to do so. -

Buried Treasures Volume Xvi No

BURIED TREASURES VOLUME XVI NO . 4 OCTOBER 1984 AND .• 1 · ~ (/) ~ + c::> ' ...--...._ a:- ("') C) A-. _.j ,..,., .- u- ....... ~ } . I Pultllahed tty CENTRAL FLORIDA GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY ORLANDO, F~ORIDA TABLE OF CONTENTS President's Message . .. 70 Rex Beach--Non-Conformist. 71 Pineys . .. ' 73 Eber Bradley (1761-1841) and Some Relatives. 74 :Genealogical Abstract of a Standard History of Freemasonry in the State of New York, Vol. II. ... 76 James Dallis Ti l lis 1873-1943 ..... 78 .. Partial 1840 Census of Pike County, IL 80 Causes of Death--Missouri Style! . 81 Geneva Cemetery , Seminole County , FL • • 82 The History of the First Baptist Church of Conway. 86 Queries .. .. 89 Surname Index .. 91 Geographical Index • 92 I . FALL CONTRIBUTORS Carrie Hull Boswell Alberta Louise Tillis Cobia Opal Tillis Flynn . \ ~ . Betty Brinsfield Hughson Verna Hartman McDowell Allen Taylor Jean Geisler Vogelius Andrea Hickman White Grace L. Young BURIED TREASURES - i - V16#4-0ct 1984 p RE SI v E NTIs M Ess A G E Oc.tobe.Jt 7984 Veak Membe.Jt~ and F~~e~, I am hono~ed to be yo~ new P~e~~dent and ~halt endeavok to ~eAve you to the be~t o6 my ab~l~ty 6o~ the next yeak. Yo~ ~up po~t and loyalty w~ll help the Soc.~ety to g~ow and to bec.ome mo~e help6ul to eve.Jtyone. Yo~ new Boakd o6 V~ec.tM~ hM ~takted to make plaM 6M the c.om~ng yeak, but we need help 6~om all o6 you. A~ you know, wokk~ng togethe.Jt w~tl make ~ g~ow togethe.Jt. -

VITAL RECORDS from ALASKA DAILY EMPIRE 1921-1925 JUNEAU, ALASKA VOLUME II Compiled by Betty J. Miller Copyright May 1996 All

VITAL RECORDS FROM ALASKA DAILY EMPIRE 1921-1925 JUNEAU, ALASKA VOLUME II Compiled by Betty J. Miller Copyright May 1996 All Rights Reserved Betty J. Miller 2551 Vista Drive #C-201 Juneau, Alaska 99801 FOREWORD Another two years out of my busy life and Volume II is completed! This reference book covers vital statistical records abstracted from the Juneau Alaska Daily Empire from 1921 through 1925. The response and sales of Volume I (1916-1920) certainly was an encouragement for me to continue the research. I suspect there will be a Volume III sometime in the future. Keep in mind when perusing the alphabetical index that the names appearing there are exactly the way they were printed in the newspaper, i.e. some were incorrectly spelled. Check the variations of spellings for surnames. I've cross-referenced where I detected misspellings. It helps to have lived in Juneau all my life and have an awareness of some of these long-time Juneau family names. Copies of these newspaper articles referenced in this book can be made at the Alaska State Library at [email protected] or 907-465-2920 in Juneau. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wouldn't be able to undertake these projects without the cooperation of the Alaska State Library allowing me to take microfilm from their library for weeks at a time. Once again the Family History Center at the LDS Church allowed me to use their library and microfilm reader whenever I needed—which was a couple hours every day. My wonderful husband helped me proofread while we were on vacation this winter. -

Placer-Mining in British Columbia

BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES €Ion. 11'. A. MCKENEIE,Minister. ROBE DUNN,Deputy Xinister. J. D. GALLOWAY, ProvincinlMineralogist. J. DICKSON,Chief Inspector of Mines. BULLETIN No. 1, 1931 PLACER-MINING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA COMPILED BY JOHN D. GAI;LOVVAY, Provincial Mineralogist. PRINTED BY AUTROKITY OF TAB LEGISLATIVE ASSENBLY. I .._ .. To the Eon. W. A. McKenzie, dlinister of Miines, Victoria, B.G. SIR,-I beg tosubmit herewith a Special bulletin on Placer-mining in British Columbia. This bulletin is in part a reprint of Bnlletio No. 2, 1930, but contains additional information on placer-mining, particularlyrelating to activities during the fieldseason of 1931. Of decided interest is the special report by Dr. R. TV. Rrock on the nlacer possibilities of the Pacific Great Eastern Railway lands. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, JOHN D. GALLOWAY, Provincial Mineralogist. Bureau of aches, Victoria, B.G., September 3rd. 1931. PLACER-MINING I[N BRITISH COLUMBIA. GENER.AL SUMMARY. BY JOHND. GALLOWAY,PROVIKCIAL IIIIKERALOQIST. INTRODUCTION. During 1931 muchinterest has been shown in placer-mining. Prospectinghas been par. ticularly active as many men, finding employment difficult to obtain, hare scoured the hills with gold-pan and shovel in search of the yellow metal, which is now more firmly entrenched as the Symbol of real value than eyer before. Development of placer properties has been vigorously prosecuted and productive hydraulics are enjoyinga successful year. The placer-output will uudoubtedly show a substantial increase for the year, as preliminary figuresindicate that largeramounts of ?:old are beingrecovered in the importantareas of Cariboo and Atlin. -

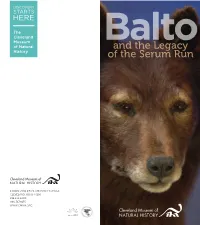

And the Legacy of the Serum Run

Baltoand the Legacy of the Serum Run 1 WADE OVAL DRIVE, UNIVERSITY CIRCLE CLEVELAND, OHIO 44106 216.231.4600 800.317.9155 WWW.CMNH.ORG Nome, Alaska, appeared on the map during one of the world’s great gold rushes at the end of the 19th century. Located on the Seward Peninsula, the town’s population had swelled to 20,000 by 1900 after gold was discovered on beaches along the Bering Sea. By 1925, however, much of the gold was gone and scarcely 1,400 people were left in the remote northern outpost. Nome was icebound seven months of the year and the nearest railroad was more than 650 miles away, in the town of Nenana. The radio telegraph was the most reliable means by which Nome could communicate with the rest of the world during the winter. Since Alaska was a U.S. territory, the government also maintained a route over which relays of dog teams carried mail from Anchorage to Nome. A one- way trip along this path, called the Iditarod Trail, took about a month. The “mushers” who traversed the trail were the best in Alaska. A RACE FOR LIFE JANUarY 27 The serum arrived in Nenana by train, and the relay to the On January 20, 1925, a radio signal went out, carried for stricken city began. “Wild Bill” Shannon lashed the life- miles across the frozen tundra: saving cargo to his sled and set off westward. Except for the Nom e c alling... dogs’ panting and the swooshing of runners on the snow, No m e c alling.. -

Alexander Mckenzie, Boss of North Dakota 1883-1906 Kenneth J

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 6-1-1949 Alexander McKenzie, Boss of North Dakota 1883-1906 Kenneth J. Carey Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Carey, Kenneth J., "Alexander McKenzie, Boss of North Dakota 1883-1906" (1949). Theses and Dissertations. 463. https://commons.und.edu/theses/463 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alexander licKenzie, Boss of North Dakota 188.?-1906 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Department of the University of North Dakota by Kenneth J. Carey u In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts June, 1949 < £ 3 Ti ls thesis, offered by Kenneth J. C*rey, as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art at the University of North Dakota, is hereby approved by the committee under whom the work has been done. vTsIon 3c N/V9 3c A 0 KN 0 WLED G3K 3 NT 3 The author wishes to extend his appreciation to the people who have made this thesis possible. Dr. Elwvn B. Robinson, who took purest interest in, and who worked diligently witn o.iie author in preparing this work, deserves soecial acknowledgment. Dr. Feli-v J. Vondracek -ave inspiration to the author in iie interest in historical study. -

Vllg.Com Type Supply Balto

TYPE SUPPLY Balto vllg.com Balto TYPE SUPPLY Balto ABOUT vllg.com I have a longstanding passion for the classic American Gothic typeface style. The style dates back over a century, and like so many things American, its origins can be traced across the ocean and through generations. There have been numerous interpretations of the style, but, frankly, none of them capture the unpretentious, sturdy and versatile soul that I admire so much. I have been working on capturing these attributes in my own version of the style for as long as I have been drawing typefaces. TYPE SUPPLY Balto ABOUT vllg.com In Balto, I have focused on emphasizing the base ideas of the style rather than particular visual attributes, quirks or artifacts of bygone type technologies. This allowed me to rethink many common assumptions about the shapes of the letterforms and the result is a clean, modern typeface that honors the noble history of the American Gothic. TYPE SUPPLY Balto ABOUT vllg.com WEIGHTS & StYLES 8 feature-rich OpenType weights in Roman & Italic Thin Thin Italic Light Light Italic Book Book Italic Medium Medium Italic Bold Bold Italic Black Black Italic Super Super Italic Ultra Ultra Italic TYPE SUPPLY Balto ABOUT vllg.com TYPE SUPPLY Tal Leming / 2014 Hello, I’m Tal Leming. Type Supply is me. Well, technically it’s the Limited Liability publications, brands and so on. It’s a lot of fun and I’m lucky to be able to work with Corporation that I work for. Anyway, I design fonts and lettering. It’s fun. -

National Trails System Act

Connecting Trails Across the Nation . National scenic trails are 100 miles or longer, continuous, primarily non- motorized routes of outstanding recreation opportunity. Such trails are established by Act of Congress. National historic trails commemorate historic (and prehistoric) routes of travel that are of significance to the entire Nation. They must meet all three criteria listed in Section 5(b)(11) of the National Trails System Act. Such trails are established by Act of Congress. National recreation trails, also authorized in the National Trails System Act, are existing regional and local trails recognized by either the Secretary of Agriculture or the Secretary of the Interior upon application. Sources: National Park Service Website . Appalachian National Scenic Trail . Continental Divide National Scenic Trail . Ice Age National Scenic Trail . Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail . Arizona Trail . Florida Trail . Natchez Trace National Scenic Trail . New England National Scenic Trail . North Country National Scenic Trail . Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail . Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail . The Appalachian Trail is a 2,180+ mile long public footpath that traverses the scenic, wooded, wild, and culturally resonant lands of the Appalachian Mountains. Conceived in 1921, built by private citizens, and completed in 1937, today the trail is managed by the National Park Service, US Forest Service, Appalachian Trail Conservancy, numerous state agencies and thousands of volunteers. The Appalachian Trail spans from Maine to Georgia (through 14 different states), with the highest point being Clingman’s Dome in Tennessee. Less than 15,000 people have successfully thru hiked the trail. *Sources: National Park Service Website . The Ice Age National Scenic Trail is a thousand- mile footpath that highlights these landscape features as it travels through some of the state’s most beautiful natural areas. -

The Golden Collar

The Golden Collar By Shadow-d-husky Steele sat alone in an alley, sulking and feeling sorry for himself. Ever since the dogs found out about his deeds during the serum run, he had been branded an outcast. He had no friends, save Shadow. Shadow was a purebred black and white husky, like Steele, who had moved up in the ranks to become lead dog of one of the sled teams in Nome. Shadow had found Steele sad and alone in the gold dredger (boiler room), where the other dogs left him. He tried to help Steele. "It takes a real dog to have the backbone to admit their mistakes,” Steele remembered Shadow saying. “Is this the legacy you wish to leave of yourself; ‘Steele, the dog who almost sabotaged the serum run and caused the death of half the population of Nome?’ Why don’t you quit feeling sorry for yourself and apologize. Who knows, maybe someday you will even be looked up to again.” Steele appreciated Shadow’s friendship, and even the notion that he was trying to improve his situation. But what did he know? Steele thought his situation was unique; it wasn’t his fault, it was all Balto’s fault. Or was it? All Steele could be sure of at this point was that everyone hated him while at the same time they considered Balto a hero. “That wolfdog gets all the glory and all I get is scorn.” Steele muttered to himself. “If that wolfdog were not around, maybe everyone would take me back.” But Steele would have to do something incredible to win back the respect of the town.