A Mutualistic Feeding Association Between Boat-Tailed Grackles And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disney•Pixar's “Finding Dory”

Educator’s Guide GRADES 2-6 Created in partnership with the Educational Team isney•Pixar’s “Finding Dory” welcomes back to the big convinced his biological sonar skills are on the fritz; and Dscreen everyone’s favorite forgetful blue tang Dory Destiny (voice of Kaitlin Olson), a nearsighted whale shark. (voice of Ellen DeGeneres), who’s living happily in the reef Deftly navigating the complex inner workings of the MLI, with Marlin (voice of Albert Brooks) and Nemo (voice Dory and her friends discover the magic within their flaws, of Hayden Rolence). When Dory suddenly remembers friendships and family. that she has a family out there who may be looking for Directed by Andrew Stanton (“Finding Nemo,” “WALL•E”), her, the trio takes off on a life-changing adventure across co-directed by Angus MacLane (“Toy Story OF TERROR!”), the ocean to California’s prestigious Marine Life Institute and produced by Lindsey Collins (co-producer “WALL•E”), (MLI), a rehabilitation center and aquarium. In an effort to Disney•Pixar’s “Finding Dory” swims home on Digital find her mom (voice of Diane Keaton) and dad (voice of HD October 25 and on Blu-ray™ November 15. For Eugene Levy), Dory enlists the help of three of the MLI’s more information, like us on Facebook, https://www. most intriguing residents: Hank (voice of Ed O’Neill), a facebook.com/PixarFindingDory, and follow us on Twitter, cantankerous octopus who frequently gives employees https://twitter.com/findingdory and Instagram, https:// the slip; Bailey (voice of Ty Burrell), a beluga whale who is instagram.com/DisneyPixar. -

Blue Water Spawning by Moorish Idols and Orangespine Surgeonfish in Palau: Is It a “Suicide Mission”?

aqua, International Journal of Ichthyology Blue Water Spawning by Moorish Idols and Orangespine Surgeonfish in Palau: Is it a “Suicide Mission”? Mandy T. Etpison1 and Patrick L. Colin2 1) Etpison Museum, PO Box 7049, Koror, Palau 96940. Email: [email protected] 2) Coral Reef Research Foundation, PO Box 1765, Koror, Palau 96940. Email: [email protected] Received: 13 December 2017 – Accepted: 05 March 2018 Keywords am Morgen zu den Laichplätzen, schlossen sich zu Gruppen Predation, aggregation, feeding frenzy, gray reef shark, zusammen und bewegten sich über der Rifffläche auf und lunar periodicity. ab und zogen dabei die Aufmerksamkeit von Beutegreifern auf sich. Um die Mittagszeit steigen sie vom Riff auf und Abstract begeben sich ins freie Wasser jenseits vom Riff. Graue Spawning aggregations of the moorish idol (MI) and or- Riffhaie folgen ihnen, greifen sie an der Oberfläche an und angespine surgeonfish (OSS) were found on the western verzehren viele von ihnen in einem Fressrausch. Ein hoher barrier reef of Palau. MI aggregated around the first quar- Prozentsatz der aufsteigenden erwachsenen HF wird von ter moon from Dec. to Mar., with largest groups in Jan. den Haien gefressen, nur wenige können in die sichere Zone and Feb. Fish arrived near the sites in the morning, des Riffs zurückkehren. KD versammeln sich in denselben grouped together and moved up and down the reef face up Monaten, aber in der Zeit des letzten Mondviertels – wobei in late morning attracting the attention of predators. At es hierüber weniger Berichte gibt. Die Beobachtungen bei mid-day they ascend from the reef out into open water beiden Fischarten, dass sie weit nach oben steigen und sich away from the reef. -

Barnacle Feeding Frenzy

Science Unit: Marine Biodiversity: Global Ocean to the Salish Sea Lesson 4: Barnacle Feeding Frenzy Summary: Students observe live barnacles feeding (it’s often a wonderful surprise for students to discover that barnacles are living things!) They then conduct an inquiry and collect data to determine if barnacle feeding speed changes in two water temperatures. Lesson type: Live animal observations Grade level: Presented to grade 3; appropriate for grades K – 12 with age appropriate modifications Duration of lesson: 75 min Developed by: Jonathan Kellogg (Scientist); Andrea Teschner and Gillian Wilson-Haffenden (Teachers) Developed for: Lord Kitchener Elementary School Year: 2016-2017 Notes: Requires live barnacles from a local beach and sea water at two temperatures Connections to BC Curriculum Biodiversity in the local environment, Making observations about living things in the local environment, Collect simple data, Identify questions about familiar objects that can be investigated scientifically, Make predictions based on prior knowledge, Knowledge of local First Peoples, Use tables, simple bar graphs, or other formats to represent data and show simple patterns and trends, Compare results with predictions, suggesting possible reasons for findings. Objectives a) Observe live barnacles feeding in a cup of seawater and document these observations b) Predict and determine how barnacle behaviour changes with different seawater temperatures c) Learn how barnacles use their cirri (feet) to move water over their body when feeding Materials • Clear plastic cocktail • Small barnacle covered rocks • Drawing or Graphing paper cups (1 rock per student pair) • Small cooler to hold • Food colouring • Seawater to fill milk jugs. Allow one barnacles to warm to room temperature, but • Two 4L milk jugs keep the other in the refrigerator. -

Iotc–2013–Wpeb09–Inf17 Glossary of Scientific Terms, Acronyms and Abbreviations, and Report Terminology Glossary

IOTC–2013–WPEB09–INF17 GLOSSARY OF SCIENTIFIC TERMS, ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, AND REPORT TERMINOLOGY SC15. Para. 19: NOTING paper IOTC–2012–SC15–INF03 which provided a glossary of scientific terms, acronyms and abbreviations, and report terminology, for the most commonly used scientific terms in IOTC reports and Conservation and Management Measures (CMM), the SC ENCOURAGED all authors of papers to be submitted to the IOTC to use the definitions contained in the glossary. The SC indicated that it may wish to modify these incrementally in the future. LAST UPDATED: 13 SEPTEMBER, 2013 GLOSSARY A Age–length (age–length key or curve). Relationship between age and length. Age-structured assessment. Assessment of the status of a fish stock based on the relative abundances of fish of different ages in the stock. Aggregation. Group of fish that comes together, often to feed or spawn. Archival tag (tagging). Implanted fish tag that detects and records („archives‟) environmental variables (e.g. water temperature) and location over time. Area closure. Closure of a given area/fishing ground for a defined period as a tool in the management of a fishery. Artisanal fishing. Fishing for subsistence using traditional methods. Autonomous adjustment. An ongoing structural adjustment process that occurs in all fisheries. As technologies and prices change, the characteristics of the fishing fleet required to maximise the net value from the fishery will also change and, as a result, fishery fleet behaviour has a tendency to change in line with market signals. The primary role for government in structural adjustment is to establish a management regime that removes any incentives that lead to over-capacity, and that facilitates autonomous adjustment to occur in response to changing economic and biological conditions. -

S-189 Cruise Report

Cruise Report S-189 Scientific data collected aboard SSV Robert C. Seamans San Diego – La Paz – Puerto Vallarta 16 October 2003 – 24 November 2003 Sea Education Association Woods Hole, Massachusetts To obtain unpublished data, contact the SEA data archivist: Erik Zettler, Science Coordinator Sea Education Association P.O. Box 6 Woods Hole, MA 02543 Phone: 508-540-3954 ext. 29 800-552-3633 ext. 29 Fax: 508-457-4673 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.sea.edu 2 Table of Contents Ship’s Company 4 Introduction 5 Table 1: Student research projects, cruise S-189 6 Table 2: Academic lectures and activities 7 Data Description 8 Figure 1: S-189 cruise track 8 Figure 2: Locations of oceanographic sampling stations 9 Table 3: Oceanographic sampling stations 10 Table 4: Surface station data 15 Table 5: Neuston net tow data 16 Table 6: Hydrocast bottle data 18 Scientific Results: Student Abstracts 22 Figures 3-25: Selections from student research papers Tables 7,8: Selections from student research papers 3 Ship’s Company SSV Robert C. Seamans, Cruise S-189 Nautical Staff Elliot Rappaport Captain Pamela Coughlin Chief Mate Ben McKee Second Mate Carter Cassel Third Mate Gray Stockmayer Engineer Jonathan Cedar Assistant Engineer Christopher Wang Steward Gillian Faustine Deckhand Scientific Staff Kara Lavender Chief Scientist Jim Watkins First Assistant Scientist Sarah Piwinski Second Assistant Scientist Cina Loarie Third Assistant Scientist Students Natalie Ashton Northeastern University Lauren Burk University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Katherine Cohn Oberlin College Meredith Costa University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Kyle Detwiler Princeton University Matthew Fromboluti Carleton College Michael King Colby College Erin Knight Hamilton College Mark Kuske Oregon State University Elizabeth Lovelock University of Pennsylvania Coleen MacNally Hamilton College Brenna Mahoney Cornell University Michael-Ryan McCabe Georgia Institute of Technology Kristen Mitchell Eckerd College Laura Nelson Dartmouth College Sara Nelson University of Arizona William Palmieri St. -

Marine Invertebrates: Communities at Risk

Biology 2013, 2, 832-840; doi:10.3390/biology2020832 OPEN ACCESS biology ISSN 2079-7737 www.mdpi.com/journal/biology Review Marine Invertebrates: Communities at Risk Jennifer Mather Psychology Department, University of Lethbridge, 4401 University Drive, Lethbridge, AB, T1K 3M4, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-403-329-2423; Fax: +1-403-329-2555 Received: 17 April 2013; in revised form: 4 June 2013 / Accepted: 5 June 2013 / Published: 10 June 2013 Abstract: 2XU GHILQLWLRQ RI WKH ZRUG µDQLPDO¶ FHQWHUV RQ YHUWHEUDWHV \HWRIWKH animals on the planet are invertebrates, about which we know little. In addition, although the Census of Marine Life (COML.org) has recently conducted an extensive audit of marine ecosystems, we still do not understand much about the animals of the seas. Surveys of the best-known ecosystems, in which invertebrate populations often play a key role, show that the invertebrate populations are affected by human impact. Coral animals are the foundation of coral reef systems, which are estimated to contain 30% of the species in the ocean. Physical impact and chemical changes on the water severely damage these reefs, and may lead to the removal of these important habitats. Tiny pteropod molluscs live in huge numbers in the polar seas, and their fragile shells are particularly vulnerable to ocean acidification. Their removal would mean that fishes on which we depend would have a hugely diminished food supply. In the North Sea, warming is leading to replacement of colder water copepods by warmer water species which contain less fat. This is having an effect on the birds which eat them, who enrich the otherwise poor land on which they nest. -

Krill Is an Increasingly Valuable Commodity Which Has an Untapped Biomass in the Southern Ocean

Krill is an increasingly valuable commodity which has an untapped biomass in the Southern Ocean. A review of biomass considerations when setting fishing quotas will be reviewed taking into account other significant food web species such as the Antarctic silverfish. Krill in General Antarctic krill or Euphausia superba is considered as a central component to the Antarctic food web. It has been written that different parts of the marine ecosystem are made up of predators that rely directly or indirectly on the heath of the krill within the system (Gascón & Werner, 2005). It is one of the most successful animal species on the plant, with a biomass that may be the largest of any creature on the planet, is recorded as having the largest aggregation of marine life and have the most powerful prteolytic enzymes found on earth (Gascón & Werner, 2005). As krill mature, they congregate in swarms or schools, with thousands of krill packed into a cubic metre of water, which can be kilometres deep or wide (Gascón & Werner, 2005). This swarming behaviour is what is attractive to commercial fishing. Mostly these swarms form at depth, and only rise to the surface at night (Nicol & Endo, 1999), which then causes a feeding frenzy for surface predators when they appear. The Antarctic Food Web Species within an ecosystem are connected in many ways, and when one species feeds upon another is the considered as the most significant, called a trophic relationship (Fuiman, Davis, & Williams, 2002; Pinkerton, Hanchet, & Bradford- Grieve, 2007). Hence fishing one species can affect many others through the trophic connection (Pinkerton, Hanchet, & Bradford-Grieve, 2007). -

A River Runs Through Us

Winterim 2013 Freshwater 512 Practicum: Reconciliation Arch and Ecology Professors John Janssen and Jim Wasley A River Runs Through Us There is a “river” that exits the Currently this stream fl ows under- The charge to the class was to A healthy stream has a diverse The SFS student posters are a fi rst Aquaculture Facility at the School ground via a storm sewer to the convert this artifi cial subterranean micro-to macrobiota that captures step toward integrating biology and of Freshwater Sciences. Kinnickinnic River. The discharge stream to a demonstration stream and processes particulate inputs landscape architecture into a pre- is clean enough that the water capable of sustaining biotic diver- and excess inorganic nutrients. liminary design concept for an eco- does not need to be treated. sity. logically-functional and aesthetic artifi cial stream. Project Background The ability to reduce erosion was another key factor in wetland marsh Figure 3: Height The purpose of this project is to design an urban stream to plant choices. Since the marsh wetland and stream are being profile of proposed compliment the design for the UWM Harbor Campus. The constructed over a liner, it is essential to reduce erosion and substrate Establishing an Invertebrate Community for Water Quality Improvement re-suspension. Excess loss of sediment would result in the need for wetland plants. Dylan Olson January 2013 constructed urban stream will transport fish effluent from the Courtesy of Paula FWS 512 substrate additions which would disturb established habitat within the : Arch 636 : Winterim 2013 : aquaculture facility at the Great Lakes Water Institute to the harbor. -

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

ATLANTIC BLUEFIN TUNA 5/2/2011 How Humankind is Eating the Species off the Planet Walter S. Via BIS Conservation Biology (Biology & Environmental Science and Policy) George Mason University BIS 490 – Dr. Aaron Winters Mentor – Dr. Chris Parsons Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Table of Contents List of Figures ..................................................................................................... 2 Acronym Glossary ............................................................................................ 2 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 4 Literature Review ............................................................................................. 6 Demand for Sushi ...................................................................................... 6 Biology .......................................................................................................... 8 Economics .................................................................................................. 10 Regulation ................................................................................................. 12 International Trade ................................................................................... 12 The Fishing Industry ............................................................................... 13 Illegal Trade ........................................................................................ -

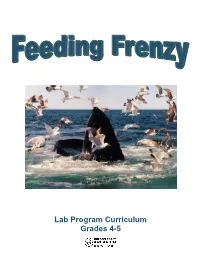

Lab Program Curriculum Grades 4-5

Lab Program Curriculum Grades 4-5 Program Description This 45–60 minute on-site lab program introduces students to food chains and food webs of the Oregon coast. During this program students and their chaperones will travel to four stations and discover who eats who while finding out about feeding adaptations. Students will also have an opportunity to touch some of the marine invertebrates discussed in this program. Participating in this program and using the enclosed activities will help your students meet ODE Science Content Standards and national Ocean Literacy Principles. Chaperones will be asked to take an active role in the lab program, which is designed so that they read informational cards to the students in their group. It will also be the chaperone’s responsibility to monitor the students’ behavior during the lab program. Before your visit: Make a KWL chart. Have the students write down what they Know about their fieldtrip, the Aquarium, the beach, etc. and then have them write down what they Want to know. Revisit this chart at the conclusion of your trip with what they Learned. Use the Animal Flash Cards to familiarize students with organisms that will be covered in their Aquarium visit. Use the Web Words reading and word search activity to familiarize students with the concepts that will be covered in the lab and terminology that might be new to them. During your visit: Provide your students and chaperones with copies of the Oregon Coast Aquarium Self Guided Materials. A master copy of the pages needed to create this booklet can be found on the Teacher Resources page at the Aquarium website, www.aquarium.org After your visit: Test the students’ skill by creating silent food chains using the ocean plant and animal cards you made. -

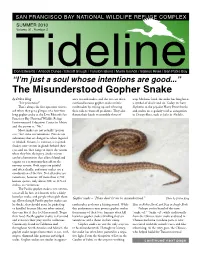

The Misunderstood Gopher Snake

SUMMER 2010 Volume 31, Number 2 “I’m just a soul whose intentions are good...” The Misunderstood Gopher Snake by Debra King ance to rattlesnakes, and the two are often atop Medusa’s head, the snake has long been “Is it poisonous?” confused because gopher snakes mimic a symbol of deceit and sin. Today, we have That’s always the first question visitors rattlesnakes by coiling up and vibrating Slytherin in the popular Harry Potter books ask when they get a glimpse of a four-foot their tails to warn off predators. They also and snakes are regularly used as antagonists long gopher snake at the Don Edwards San flatten their heads to resemble those of in Disney films, such as Jafar inAladdin , Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge Environmental Education Center in Alviso, and the answer is, “No.” Most snakes are not actually “poison- ous,” but some are venomous. Poisons are substances that are dangerous when ingested or inhaled. Venom, in contrast, is injected. Snakes store venom in glands behind their eyes and use their fangs to inject the venom when they bite their prey. Snake venom can be a hemotoxin that affects blood and organs, or a neurotoxin that affects the nervous system. Both types are painful and often deadly, and many snakes use a combination of the two. Not all snakes are venomous, however. Of more than 2,700 known species, only about 300, or 11% of snakes, are venomous. The Pacific gopher snake is not venom- ous at all. In fact, it is known to be a fairly harmless snake, and people often pick them Gopher snake – “Please don’t let me be misunderstood.” Photo by Debra King up. -

Mississippiensis)

Animal-Borne Imaging Reveals Novel Insights into the Foraging Behaviors and Diel Activity of a Large-Bodied Apex Predator, the American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) James C. Nifong1*, Rachel L. Nifong2, Brian R. Silliman1, Russell H. Lowers3, Louis J. Guillette Jr.4, Jake M. Ferguson1, Matthew Welsh5, Kyler Abernathy6, Greg Marshall6 1 Department of Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, United States of America, 2 School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, United States of America, 3 InoMedic Health Applications, Merritt Island, Florida, United States of America, 4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Hollings Marine Laboratory, Medical University of Charleston South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, United States of America, 5 Guana Tolomato Matanzas National Estuarine Research Reserve, Marineland, Florida, United States of America, 6 National Geographic Remote Imaging, Washington, District of Columbia, United States of America Abstract Large-bodied, top- and apex predators (e.g., crocodilians, sharks, wolves, killer whales) can exert strong top-down effects within ecological communities through their interactions with prey. Due to inherent difficulties while studying the behavior of these often dangerous predatory species, relatively little is known regarding their feeding behaviors and activity patterns, information that is essential to understanding their role in regulating food web dynamics and ecological processes. Here we use animal-borne imaging systems (Crittercam) to study the foraging behavior and activity patterns of a cryptic, large- bodied predator, the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) in two estuaries of coastal Florida, USA. Using retrieved video data we examine the variation in foraging behaviors and activity patterns due to abiotic factors.