The Syntax of Cimbrian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Among All Kinds of German Language Still Spoken, Cimbrian Is

A Shakespearean Sonnet in Cimbrian – or Perpetuating the Old Mystery by Remigius Geiser Among all kinds of German languages still spoken, Cimbrian1 is undoubtedly the oldest one. Its origin is lost in the mystery of history. Some think it derives from Bavarians and Tyroli- ans, who settled in Northern Italy during the 11th and/or 12th century. Others derive it from the last remainder of the Langobards, who spoke a language very similar to medieval Bavarian or Tyrolian. There are also scolars connecting it to the last Goths … Cimbrian is nowadays still spoken by a few hundred people – nobody has counted their exact number so far – all of them Italian citizens nowadays in three provinces of Northern Italy: Vicenza, Verona and Trentino. They all speak Italian as well, and two hundred years ago Cimbrian was already said to be dying out before the beginning of the 20th century, but has now reached the third millennium. There are still three communities speaking Cimbrian today. The one we are dealing with in particular is the so-called “Sette Comuni”, the "Siban Komàüne" on the Plateau of Asiago, the Altopiano di Asiago, which is situated between Vicenza and Trent in the province Vicenza. In contrast to all other Cimbrian communities, they were a politically autonomous Alpine rural republic, comparable to Switzerland, from about 1200 AD until the times of Napoleon. Such a status of considerable political independence enabled the Sette Comuni to develop their vari- ant of Old High German into a standard literary language that was applied to various func- tions, especially religion and literature. -

Detecting Genetic Isolation in Human Populations: a Study of European Language Minorities

Detecting Genetic Isolation in Human Populations: A Study of European Language Minorities Marco Capocasa2,3, Cinzia Battaggia1, Paolo Anagnostou1,3, Francesco Montinaro4, Ilaria Boschi4, Gianmarco Ferri5, Milena Alu` 5, Valentina Coia6¤, Federica Crivellaro7, Giovanni Destro Bisol1,2* 1 Dipartimento di Biologia Ambientale, Universita` ‘‘La Sapienza’’, Rome, Italy, 2 Dipartimento Biologia e Biotecnologie ‘‘Charles Darwin’’, Universita` La Sapienza, Rome, Italy, 3 Istituto Italiano di Antropologia, Rome, Italy, 4 Facolta di Medicina, Istituto di Medicina Legale, Universita` Cattolica, Rome, Italy, 5 Dipartimento ad Attivita` Integrata di Laboratori, Anatomia Patologica, Medicina Legale, Struttura Complessa di Medicina Legale, Universita` di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy, 6 Dipartimento di Filosofia, Storia e Beni culturali, Universita degli Studi di Trento, Trento, Italy, 7 Division of Biological Anthropology, Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies, Cambridge, United Kingdom Abstract The identification of isolation signatures is fundamental to better understand the genetic structure of human populations and to test the relations between cultural factors and genetic variation. However, with current approaches, it is not possible to distinguish between the consequences of long-term isolation and the effects of reduced sample size, selection and differential gene flow. To overcome these limitations, we have integrated the analysis of classical genetic diversity measures with a Bayesian method to estimate gene flow and have carried out simulations based on the coalescent. Combining these approaches, we first tested whether the relatively short history of cultural and geographical isolation of four ‘‘linguistic islands’’ of the Eastern Alps (Lessinia, Sauris, Sappada and Timau) had left detectable signatures in their genetic structure. We then compared our findings to previous studies of European population isolates. -

Reflections on Diversity Linguistics: Language Inventories and Atlases

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 15 Reflections on Language Documentation 20 Years after Himmelmann 1998 ed. by Bradley McDonnell, Andrea L. Berez-Kroeker & Gary Holton, pp. 122–131 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ 12 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24814 Reflections on diversity linguistics: Language inventories and atlases Sebastian Drude University of Iceland Goethe-Universität Frankfurt This contribution gives a short overview of “language inventorying”: research aiming at creating comprehensive catalogues and atlases of all the languages in the world, which has seen a boost with the renewed interest in linguistic diversity triggered by the awareness of language endangerment in the 1990s. By focusing on the development of the ISO standard 639 and SIL’s Ethnologue, the main advances and issues in this area are discussed. The overview concludes by presenting the major alternative resources, in particular Glottolog. The label “diversity linguistics” has been introduced by Martin Haspelmath and others at the Max-Planck-Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig.1 To my knowledge, it was first used in the context of the final conference of that institute’s department of linguistics (MPI-EVA 2015). Now there exist a number of activities under this label, including a book series “Studies in Diversity Linguistics” (Haspelmath 2014ff). In a broad sense, the term designates those branches of linguistics that show interest in the diversity of languages, their structure and relationship: descriptive linguistics (especially of previously understudied languages, often in a fieldwork setting), language typology, and comparative linguistics. Language Documentation is included in or at least a close neighbor to this group. -

The Cimbri of Denmark, the Norse and Danish Vikings, and Y-DNA Haplogroup R-S28/U152 - (Hypothesis A)

The Cimbri of Denmark, the Norse and Danish Vikings, and Y-DNA Haplogroup R-S28/U152 - (Hypothesis A) David K. Faux The goal of the present work is to assemble widely scattered facts to accurately record the story of one of Europe’s most enigmatic people of the early historic era – the Cimbri. To meet this goal, the present study will trace the antecedents and descendants of the Cimbri, who reside or resided in the northern part of the Jutland Peninsula, in what is today known as the County of Himmerland, Denmark. It is likely that the name Cimbri came to represent the peoples of the Cimbric Peninsula and nearby islands, now called Jutland, Fyn and so on. Very early (3rd Century BC) Greek sources also make note of the Teutones, a tribe closely associated with the Cimbri, however their specific place of residence is not precisely located. It is not until the 1st Century AD that Roman commentators describe other tribes residing within this geographical area. At some point before 500 AD, there is no further mention of the Cimbri or Teutones in any source, and the Cimbric Cheronese (Peninsula) is then called Jutland. As we shall see, problems in accomplishing this task are somewhat daunting. For example, there are inconsistencies in datasources, and highly conflicting viewpoints expressed by those interpreting the data. These difficulties can be addressed by a careful sifting of diverse material that has come to light largely due to the storehouse of primary source information accessed by the power of the Internet. Historical, archaeological and genetic data will be integrated to lift the veil that has to date obscured the story of the Cimbri, or Cimbrian, peoples. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Das Zimbrische Zwischen Germanisch Und Romanisch

1 Ermengildo Bidese, James R. Dow & Thomas Stolz (eds.) 2005. Das Zimbrische zwischen Germanisch und Romanisch. Bochum, Universitätsverlag Dr. N. Brockmey- er. [Diversitas Linguarum 9]. xiii – 240 p. Reviewed by Anthony Rowley, Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Munich Cimbrian or “Zimbrisch” is a German dialect spoken in linguistic enclaves in Northern Italy. It has been usual among dialectologists to stress the antiquity and the archaic vocabulary and morphology of these vanishing dialects, and so it is refreshing to see linguists finding a more innovative side to the language and using Cimbrian as a “linguistic laboratory” for the study of language contact and language change. The 12 papers published here, mainly by German and Italian scholars, derive from a colloquium held at Bremen University early in 2005, the most important of them being focussed on syntactic and morphosyntactic innovations in Cim- brian as typological change in response to structures of Italian. The brief introduction gives a précis of the articles’ contents, but leaves the reader totally in the dark about what Cimbrian is and where it is spoken. Individual authors do mention details in passing, and a brief survey of the sociolinguistic situation in the various enclaves is actually hidden away on p. 157, but there is no general introduction to the language and no map. Most contributions are written in German, with one in English and one (Remigio Geiser, “Vomme Gatòttareche dar Paurn zomme Hòolighen Gaprèchte – asò òch dorrèttat- sich de Zimbrische Zunga” [from the babbling of peasants to a holy language – one of the ways the Cimbrian language is being saved], pp. -

Book of Abstracts

Book of Abstracts 3rd conference on Contested Languages in the Old World (CLOW3) University of Amsterdam, 3–4 May 2018 CLOW3 Scientific Committee: Federico CLOW3 has received financial support from Gobbo (University of Amsterdam); Marco the research programme ‘Mobility and Tamburelli (Bangor University); Mauro Tosco Inclusion in Multilingual Europe’ (MIME, EC (University of Turin). FP7 grant no. 613334). CLOW3 Local Organizing Committee: Federico Gobbo; Sune Gregersen; Leya Egilmez; Franka Bauwens; Wendy Bliekendaal; Nour Efrat-Kowalsky; Nadine van der Maas; Leanne Staugaard; Emmanouela Tsoumeni; Samuel Witteveen Gómez. Additional support has been provided by John Benjamins Publishing Company. CLOW3 Book of Abstracts edited by Sune Gregersen. Abstracts © The Author(s) 2018. 2 Table of contents Paper presentations Ulrich Ammon (keynote) 4 Andrea Acquarone & Vittorio Dell’Aquila 5 Astrid Adler, Andrea Kleene & Albrecht Plewnia 6 Márton András Baló 7 Guillem Belmar, Nienke Eikens, Daniël de Jong, Willemijn Miedma & Sara Pinho 8 Nicole Dołowy-Rybińska & Cordula Ratajczak 9 Guilherme Fians 10 Sabine Fiedler 11 Federico Gobbo 12 Nanna Haug Hilton 13 Gabriele Iannàccaro & Vittorio Dell’Aquila 14 G. T. Jensma 15 Juan Jiménez-Salcedo 16 Aurelie Joubert 17 Petteri Laihonen 18 Patrick Seán McCrea 19 Leena Niiranen 20 Yair Sapir 21 Claudia Soria 22 Ida Stria 23 Marco Tamburelli & Mauro Tosco 24 Poster presentations Eva J. Daussà, Tilman Lanz & Renée Pera-Ros 25 Vittorio Dell’Aquila, Ida Stria & Marina Pietrocola 26 Sabine Fiedler & Cyril Brosch 27 Daniel Gordo 28 Olga Steriopolo & Olivia Maky 29 References 30 Index of languages 34 3 Keynote: From dialects and languages to contested languages Ulrich Ammon (University of Duisburg-Essen) The presentation begins with the explication of concepts which are fundamental and which have to be defined with sufficient clarity for the following thoughts, because terminology and concepts vary widely in the relevant literature. -

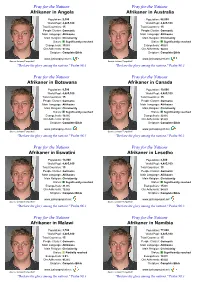

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afrikaner in Angola Afrikaner in Australia Population: 2,300 Population: 68,000 World Popl: 4,485,100 World Popl: 4,485,100 Total Countries: 15 Total Countries: 15 People Cluster: Germanic People Cluster: Germanic Main Language: Afrikaans Main Language: Afrikaans Main Religion: Christianity Main Religion: Christianity Status: Significantly reached Status: Significantly reached Evangelicals: 35.0% Evangelicals: 45.0% Chr Adherents: 97.0% Chr Adherents: 94.0% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Johann Tempelhoff Source: Johann Tempelhoff "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afrikaner in Botswana Afrikaner in Canada Population: 9,500 Population: 10,000 World Popl: 4,485,100 World Popl: 4,485,100 Total Countries: 15 Total Countries: 15 People Cluster: Germanic People Cluster: Germanic Main Language: Afrikaans Main Language: Afrikaans Main Religion: Christianity Main Religion: Christianity Status: Significantly reached Status: Significantly reached Evangelicals: 18.0% Evangelicals: 22.0% Chr Adherents: 97.0% Chr Adherents: 91.0% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Johann Tempelhoff Source: Johann Tempelhoff "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afrikaner in Eswatini -

Siben Komoine Im Land Chalchoufe Remmalju Kampel Pomatt Bersntol

VALLE DEI GRESSONEY ISSIME ALAGNA CARCOFORO RIMELLA CAMPELLO MONTI FORMAZZA MÒCHENI Greschoney Eischeme Im Land Chalchoufe Remmalju Kampel Pomatt Bersntol Comitato unitario delle isole linguistiche storiche germaniche in Italia Einheitskomitee der historischen deutschen Sprachinseln in Italien !"!"###"!"! !"!"###"!"! !"!"###"!"! !"!"###"!"! !"!"###"!"! !"!"###"!"! !"!"###"!"! !"!"###"!"! Le isole linguistiche storiche germaniche aderenti al Comitato Unitario delle Isole Linguistiche Storiche Germaniche in Italia Die historischen deutschen Sprachinseln vertreten vom Einheitskomitee der historischen deutschen Sprachinseln in Italien The historic German language enclaves represented by the Unitary Committee of historic German language Enclaves in Italy VALCANALE AUSTRIA KANALTAL Pontebba/Pontafel SVIZZERA !!" Malborghetto-Valbruna ALTOALTO ADIGEADIGE TIMAU !!" Malborgeth-Wolfsbach SÜDTIROLSÜDTIROL TISCHLBONG Tarvisio/Tarvis !"!"!"###"!"!"! FORMAZZA 0 50 km 100 km POMATT Bolzano Comitato Unitario delle Isole Linguistiche Bozen Storiche Germaniche in Italia SAPPADA Il Comitato Unitario delle Isole Linguistiche RIMELLA PLODN Storiche Germaniche in Italia è formato dai rappresentanti delle comunità germaniche REMMALJU SAURIS insediate nell’arco alpino italiano, con lo scopo di promuoverne le lingue e le culture. È stato ZAHRE fondato nell’anno 2002, in seguito ad un paio CARCOFORO di incontri promossi a partire dal 2001, proclamato dall’Unione Europea e dal Consiglio CHALCHOUFE d’Europa ”Anno Europeo delle lingue”. Nel corso SLOVENIA degli anni -

Germanic Dialects

ABBREVIATIONS . = Cp. compare. fi = 1 er n. fina . Germ . au sla utend , pertaining to a letter t n minati g a word . = ini i al G e m a u e fi s e of . init , r . nl a t nd , r t lett r word = inl m e e m of . Ger . inl au tend , l tt r in iddle word = H . G . High G erman . L . Germ an . = m M . H . G . M iddl e High G er an . = a M d . G . M idl and Germ n . = M M e a e m a . od . H . G . odern or Lit r ry High G r n E = En 0 . O l d gl i l h. = O . F. O l d Fris i an . = O . Ir. 01d Iris h . N = 0 . O l d Norse. = O . S . O l d S axon . = O . Sc . 01d Scandinavi an . = an andi na ian . Sc . or Sc d . Sc v = Skt . Sanskrit . = Sw . Swabian . r-=a e ma efi mea n m e f U G r n pr x, ni g pri itiv , . in st : Urg. m meaning primitive Ger an , W = e ma es t . G . w at Ger nic . ER M AN I DI G O ALECTS . 1 There are different opinion s concerning t he divis ion of - L the Indo Germa nic l angua ges . es kien believes tha t the origina l language from which the sepa ra te "a d o-G ermanic l angua ges are s upposed to h ave s prung firs t divid ed itself into three different dialects or branches : ( 1 ) T he s a c s s o f a s k Z e and A i ti , con i ting S n rit , nd Ar m enian the a e ia e ts of a e s a and me a , nci nt d l c Indi , P r i Ar ni ; 2 the t ea m s G eek 2 e t and ( ) Sou h Europ n , co pri ing r , C l ic a nd 3 the N E ea ai i e m a and Latin ; ( ) orth urop n , cont n ng G r nic - Sl a vo Letti c. -

Relativism and Universalism in Linguistics

Societas Linguistica Europaea SLE 39th Annual Meeting Relativism and Universalism in Linguistics 30 August-2 September 2006 Universität Bremen Organised by the Department of Linguistics and the Institute of General and Applied Linguistics (IAAS) at the University of Bremen Chief Organizer Secretary and Webmaster Prof. Dr. Thomas Stolz Prof. Dr. Karl Heinz Wagner Fachbereich 10: Linguistik Fachbereich 10: CIP-Labor Bibliothekstraße Bibliothekstraße Universität Bremen Universität Bremen Postfach 33 04 40 Postfach 33 04 40 D-28334 Bremen D-28334 Bremen Tel.: ++49(0)421/218-4993 Tel.: ++49(0)421/218-309 Fax: ++49(0)421/218-4283 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Table of Contents SLE 2006 in Bremen - welcome! 1 Organization 2 Programme Overview 3 Sections 7 Section A: Language Contact 9 Section B: Relativism vs. Universalism 21 Section C: Grammaticalization and Language Change 37 Section D: Pronouns 49 Section E: Word Order 57 Section F: Phonology 67 Section G: Verbal Categories (aspect and sundry distinctions) 75 Section H: Syntax 83 Section I: Morphology 95 Section J: Semantics / Cognition 105 Section K: Theory - Methodology 115 Section L: Discourse 121 Workshops 123 Workshop 1 (Abr): Cross-linguistic aspect/Aktionsart-modality links 125 Workshop 2 (Anc): Universalism and relativism in face-saving: Focus on postcolonial contexts 147 Workshop 3 (Cor): The encoding of evidentiality in European written and spoken discourse 157 Workshop 4 (Fer): Multilingualism and Universal Principles of Linguistic Change 167 Workshop 5 (Gro): Universalist Perspectives on Relative Properties: Features vs. Constructions of the Clausal Left Periphery 173 Workshop 6 (Had): La scalarité, concept éclaté ou outil explicatif performant? 183 Workshop 7 (Ron): Irregularity in inflectional and derivational morphology 191 Index 199 SLE 2006 in Bremen - welcome! On behalf of the organising team, I welcome all participants of the 39th Annual Meeting of the Societas Linguistica Europaea in Bremen. -

The Diversity of Languages in the Alpine-Adriatic Region I Linguistic Minorities and Enclaves in Northern Italy1

Herta Maurer-Lausegger, Diversity of languages The diversity of languages in the Alpine-Adriatic region I Linguistic minorities and enclaves in northern Italy1 HERTA MAURER-LAUSEGGER Institute of Slavic Studies, University of Klagenfurt, Austria Der im vorliegenden Beitrag präsentierte multinationale Sprachraum des Alpen-Adria Gebiets stellt zweifelsohne eines der interessantesten und vielfältigsten Kulturräume Europas dar. Durch die jahrhundertelange Symbiose slawischer, germanischer und romanischer Kultur und die bewegte historische Vergangenheit hat sich in diesen Gebieten und Regionen sukzessive eine komplexe Verflechtung von Sprachen, Varietäten, Dialekten und Mundarten entwickelt, die in vielfältigster Weise und in unterschiedlichem Ausmass aufeinander wirken. Die soziolinguistische Situation in diesen multiethnischen Gebieten ist komplex und weist regionsspezifische Besonderheiten auf, die sich in unterschiedlichster Weise manifestieren. - Einige mundartliche Existenzformen des Alpen-Adria-Gebiets sind bereits verschwunden, viele sind vom Aussterben bedroht. Der Bewahrung der am Alpenhauptkamm Norditaliens angesiedelten vielfältigen Mundarten, Dialekte und Varietäten, aber auch der Pflege der kulturellen Identität ethnischer Minderheiten wird zurzeit überall verstärkt Beachtung geschenkt. Ob und in welcher Form hier die Sprachen-, Dialekt- und Varietätenvielfalt bewahrt werden kann, wird wohl von den jeweiligen sprachpolitischen, sozioökonomischen, ethnopsychologischen, rechtli- chen u. a. Faktoren abhängig sein. Die Sprachenvielfalt