Managing Diuretic-Induced Hypokalemia in Ambulatory Hypertensive Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of Exogenous Glucocorticoid on Osmotically Stimulated Antidiuretic

European Journal of Endocrinology (2006) 155 845–848 ISSN 0804-4643 CLINICAL STUDY Effect of exogenous glucocorticoid on osmotically stimulated antidiuretic hormone secretion and on water reabsorption in man Volker Ba¨hr1, Norma Franzen1, Wolfgang Oelkers2, Andreas F H Pfeiffer1 and Sven Diederich1,2 1Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Nutrition, Charite-Universitatsmedizin Berlin, Campus Benjamin Franklin, Hindenburgdamm 30, 12200 Berlin, Germany and 2Endokrinologikum Berlin, Centre for Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases, Berlin, Germany (Correspondence should be addressed to V Ba¨hr; Email: [email protected]) Abstract Objective: Glucocorticoids exert tonic suppression of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion. Hypocortisolism in secondary adrenocortical insufficiency can result in a clinical picture similar to the syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion. On the other hand, in vitro and in vivo results provide evidence for ADH suppression in states of hypercortisolism. To test the hypothesis that ADH suppression is of relevance during glucocorticoid therapy, we investigated the influence of prednisolone on the osmotic stimulation of ADH. Design and methods: Seven healthy men were subjected to water deprivation tests with the measurement of plasma ADH (pADH) and osmolality (posmol) before and after glucocorticoid treatment (5 days 30 mg prednisolone per day). Results: Before glucocorticoid treatment, the volunteers showed a normal test with an adequate increase of pADH (basal 0.54G0.2 to 1.9G0.72 pg/ml (meanGS.D.)) in relation to posmol(basal 283.3G8.5 to 293.7G6 mosmol/kg). After prednisolone intake, pADH was attenuated (!0.4 pg/ml) in spite of an increase of posmol from 289.3G3.6 to 297.0G5.5 mosmol/kg. -

Beta-Blockers for Hypertension: Time to Call a Halt

Journal of Human Hypertension (1998) 12, 807–810 1998 Stockton Press. All rights reserved 0950-9240/98 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/jhh FOR DEBATE Beta-blockers for hypertension: time to call a halt DG Beevers University Department of Medicine, City Hospital, Birmingham B18 7QH, UK Beta-blockers are not very effective at lowering blood the endorsement of beta-blockers by the British Hyper- pressure in elderly hypertensive patients or in Afro- tension Society and other guidelines committees, Caribbeans and these two groups represent a large pro- except possibly for severe resistant hypertension, high portion of people with raised blood pressure. Further- risk post-infarct patients and those with angina pectoris. more they do not prevent more heart attacks than the The time has come to move across to newer, safer, more thiazide diuretics. Beta-blockers can also be dangerous tolerable and more effective antihypertensive agents in many hypertensive patients and even when these whilst continuing to use thiazide diuretics in low doses drugs are not contraindicated, they cause subtle and in the elderly as first choice, providing there are no depressing side effects which should preclude their contraindications. usefulness. The time has come therefore to reconsider Keywords: beta-blockers; hypertension Introduction Safety and tolerability Beta-adrenergic blockers were first introduced in the There is little doubt that the beta-blockers are the early 1960s for the treatment of angina pectoris. most unsafe of all antihypertensive drugs. They can Their antihypertensive properties were not fully precipitate or worsen heart failure in patients with recognised until the celebrated paper by Pritchard myocardial damage and they are contraindicated in and Gillam in 1964.1 They rapidly became popular patients with asthma. -

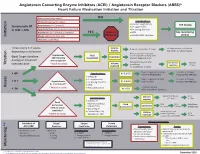

Initiation Titration Assess Monitoring **

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEI) / Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBS)* Heart Failure Medication Initiation and Titration Bilateral renal artery stenosis NO Moderate/Severe aortic stenosis Considerations: • Baseline cough (ACEi) Hyperkalemia: K+ > 5.2 mmol/L See dosing Symptomatic HF • K+ supplements or LVEF < 40% Renal Dysfunction:Serum creatinine >220 µmol/L • K+ sparing diuretics Hypotension: SBP < 90 mmHg or symptoms YES Refer to • MRA See monitoring Initiation Allergy: angioedema, hives, rash Physician • NSAIDS/COX2 inhibitors section Intolerance: cough (ACEi) Titrate every 1-3 weeks, Volume Reduce/hold diuretic x 2-3 days No improvement, hold/reduce depending on tolerance deplete ACEI/ARB x 1-2 wks & reassess Reassess diuretic dose/other Hypotension Fluid non-essential BP lowering meds Goal: Target dose(see Euvolemic SBP<90mmHg Assessment Consider staggering doses dosing) or maximum with symptoms* Reduce/hold dose of other See Diuretic Reassess Titration * Watch for trends Volume tolerated dose vasodilators algorithm 1-2 wks overload +/- ACEI/ARB x 1-2 weeks Stop K+ supplements, reduce/ Serum K+ in 3-5 days, Considerations: • BP K+ 5.2-5.5 hold MRA (if applicable) Reassess ACEI/ARB dose • Dietary K+ • K+ supplements Stop K+ supplements, MRA. Serum K+ in 2-3 days, • K + Hyperkalemia • K+ sparing diuretics K+ 5.6-6.0 hold ACEI/ARB Reassess ACEI/ARB dose K+ > 5.2 mmol/L* • MRA Assess * Watch for trends • Renal dysfunction Treat hyperkalemia • Scr K+ > 6.0 Refer to MD/NP +/- send to ED Reduce/hold diuretic Scr in Considerations: -

Energy Drinks 800.232.4424 (Voice/TTY) 860.793.9813 (Fax)

Caffeine and Energy Boosting Drugs: Energy Drinks 800.232.4424 (Voice/TTY) 860.793.9813 (Fax) www.ctclearinghouse.org A Library and Resource Center on Alcohol, Tobacco, Other Drugs, Mental Health and Wellness What are energy drinks? you. You wouldn't use Mountain Dew as a sports Energy drinks are beverages like drink. And a drink like Red Bull and vodka is Red Bull, Venom, Adrenaline Rush, more like strong coffee and whisky than 180, ISO Sprint, and Whoopass, anything else. which contain large doses of caffeine and other legal stimulants What happens when energy drinks are like ephedrine, guarana, and ginseng. combined with alcohol? Energy drinks may contain as much as 80 mg. Energy drinks are also used as mixers with of caffeine, the equivalent of a cup of coffee. alcohol. This combination carries a number of Compared to the 37 mg. of caffeine in a dangers: Mountain Dew, or the 23 mg. in a Coca-Cola Classic, that's a big punch. These drinks are • Since energy drinks are stimulants and marketed to people under 30, especially to alcohol is a depressant, the combination of college students, and are widely available both effects may be dangerous. The stimulant on and off campus. effects can mask how intoxicated you are and prevent you from realizing how much Are there short-term dangers to drinking alcohol you have consumed. Fatigue is one energy drinks? of the ways the body normally tells Individual responses to caffeine vary, and someone that they've had enough to drink. these drinks should be treated carefully • The stimulant effect can give the person the because of how powerful they are. -

The Necessity and Effectiveness of Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist in the Treatment of Diabetic Nephropathy

Hypertension Research (2015) 38, 367–374 & 2015 The Japanese Society of Hypertension All rights reserved 0916-9636/15 www.nature.com/hr REVIEW The necessity and effectiveness of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy Atsuhisa Sato Diabetes mellitus is a major cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD), and diabetic nephropathy is the most common primary disease necessitating dialysis treatment in the world including Japan. Major guidelines for treatment of hypertension in Japan, the United States and Europe recommend the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers, which suppress the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), as the antihypertensive drugs of first choice in patients with coexisting diabetes. However, even with the administration of RAS inhibitors, failure to achieve adequate anti-albuminuric, renoprotective effects and a reduction in cardiovascular events has also been reported. Inadequate blockade of aldosterone may be one of the reasons why long-term administration of RAS inhibitors may not be sufficiently effective in patients with diabetic nephropathy. This review focuses on treatment in diabetic nephropathy and discusses the significance of aldosterone blockade. In pre-nephropathy without overt nephropathy, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist can be used to enhance the blood pressure-lowering effects of RAS inhibitors, improve insulin resistance and prevent clinical progression of nephropathy. In CKD categories A2 and A3, the addition of a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist to an RAS inhibitor can help to maintain ‘long-term’ antiproteinuric and anti-albuminuric effects. However, in category G3a and higher, sufficient attention must be paid to hyperkalemia. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists are not currently recommended as standard treatment in diabetic nephropathy. -

Optimal Diuretic Strategies in Heart Failure

517 Review Article on Heart Failure Update and Advances in 2021 Page 1 of 8 Optimal diuretic strategies in heart failure Sarabjeet S. Suri, Salpy V. Pamboukian Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: SS Suri; (II) Administrative support: SV Pamboukian; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: Both authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Both authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: Both authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: Both authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: Both authors. Correspondence to: Dr. Sarabjeet S. Suri, MD. University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1900 University Blvd, THT 321, Birmingham, AL 35223, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Heart failure (HF) is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in the world. According to a 2019 American Heart Association report, about 6.2 million American adults had HF between 2013 and 2016, being responsible for almost 1 million admissions. As the population ages, the prevalence of HF is anticipated to increase, with 8 million Americans projected to have HF by 2030, posing a significant public health and financial burden. Acute decompensated HF (ADHF) is a syndrome characterized by volume overload and inadequate cardiac output associated with symptoms including some combination of exertional shortness of breath, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND), fatigue, tissue congestion (e.g., peripheral edema) and decreased mentation. The pathology is characterized by hemodynamic abnormalities that result in autonomic imbalance with an increase in sympathetic activity, withdrawal of vagal activity and neurohormonal activation (NA) resulting in increased plasma volume in the setting of decreased sodium excretion, increased water retention and in turn an elevation of filling pressures. -

Combination Therapy

Combination Antihypertensive Therapy: When to use it Diabetes George L. Bakris, MD, F.A.S.N., F.A.S.H. Professor of Medicine Director, ASH Comprehensive Hypertension Center The University of Chicago Medicine Development of Antihypertensive Therapies ? More Effective but As effective and As effective and even effective for poorly tolerated better tolerated better tolerated SBP 1940s 1950 1957 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2001- 2009 ARBs Direct Direct ACE inhibitors Renin vasodilators inhibitors α-blockers Peripheral Thiazides ETa sympatholytics diuretics Blockers Central ααα 2 Calcium Ganglion agonists blockers antagonists- VPIs Calcium DHPs Others Veratrum antagonists- alkaloids non DHPs βββ-blockers Evolution of Fixed Dose Combination Antihypertensive Therapies 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000- present Combination CCBs+ ARBs Diuretics RAS Blockers ARB + Aldactazide, with CCBs chlorthalidone Dyazide, Maxzide, DRIs +ARBs Guanabenz SerApAs RAS Blockers (Lotrel) DRIs+ CCBs (reserpine, with diuretics hydralazine, Beta blocker +diuretics TRIPLE Combos HCTZ) (CCB+RAS Blocker + diuretic) Rationale for Fixed-Dose Combination Therapy: Background • Traditional antihypertensive therapy yields goal BP in <60% of treated hypertensive patients1-3 • Switching from one monotherapy to another is effective in only about 50% of patients1 • Most patients will require at least two drugs to attain goal BP (<140/90 mm Hg, or <130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes or chronic renal disease)4-6 BP = blood pressure 1. Materson BJ et al. J Hum Hypertens. 1995;9(10):791-796. 2. Messerli FH. J Hum Hypertens. 1992;6 Suppl. 2:S19-S21. 3. Ram CV. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2004;6(10):569-577. 4. Chobanian AV, et al. JAMA. -

Intravenous Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Use in Acutely

Intravenous Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Use in Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure with Diuretic Resistance Nicolas Girerd, Matthieu Aubry, Pierre Lantelme, Olivier Huttin, Patrick Rossignol To cite this version: Nicolas Girerd, Matthieu Aubry, Pierre Lantelme, Olivier Huttin, Patrick Rossignol. Intravenous Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Use in Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure with Diuretic Resistance. International Heart Journal, International Heart Journal Association, 2021, 62 (1), pp.193- 196. 10.1536/ihj.20-442. hal-03116131 HAL Id: hal-03116131 https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/hal-03116131 Submitted on 20 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Intravenous mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist use in acutely decompensated heart failure with diuretic resistance Nicolas GIRERD1*, MD, PhD; Matthieu AUBRY2*, MD; Pierre LANTELME2,3, MD, PhD ; Olivier HUTTIN1, MD, PhD ; Patrick ROSSIGNOL1, MD, PhD. 1. Université de Lorraine, INSERM, Centre d'Investigations Cliniques 1433, CHRU de Nancy, Inserm 1116 and INI-CRCT (Cardiovascular and Renal Clinical Trialists) F-CRIN Network, Nancy, France. 2. Cardiology Department, European Society of Hypertension Excellence Center, Hôpital de la Croix- Rousse et Hôpital Lyon Sud, Hospices Civils de Lyon. 3. Université de Lyon, CREATIS, CNRS UMR5220, INSERM U1044, INSA-Lyon, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Lyon, France. -

Comparison of Effects Between Calcium Channel Blocker and Diuretics in Combination with Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker on 24-H

Oh et al. Clinical Hypertension (2017) 23:18 DOI 10.1186/s40885-017-0074-0 RESEARCH Open Access Comparison of effects between calcium channel blocker and diuretics in combination with angiotensin II receptor blocker on 24-h central blood pressure and vascular hemodynamic parameters in hypertensive patients: study design for a multicenter, double-blinded, active- controlled, phase 4, randomized trial Gyu Chul Oh1, Hae-Young Lee1, Wook Jin Chung2, Ho-Joong Youn3, Eun-Joo Cho4, Ki-Chul Sung5, Shung Chull Chae6, Byung-Su Yoo7, Chang Gyu Park8, Soon Jun Hong9, Young Kwon Kim10, Taek-Jong Hong11, Dong-Ju Choi12, Min Su Hyun13, Jong Won Ha14, Young Jo Kim15, Youngkeun Ahn16, Myeong Chan Cho17, Soon-Gil Kim18, Jinho Shin18, Sungha Park14, Il-Suk Sohn19 and Chong-Jin Kim19,20* Abstract Background: Hypertension is a risk factor for coronary heart disease and stroke, and is one of the leading causes of death. Although over a billion people are affected worldwide, only half of them receive adequate treatment. Current guidelines on antihypertensive treatment recommend combination therapy for patients not responding to monotherapy, but as the number of pills increase, patient compliance tends to decrease. As a result, fixed-dose combination drugs with different antihypertensive agents have been developed and widely used in recent years. CCBs have been shown to be better at reducing central blood pressure and arterial stiffness than diuretics. Recent studies have reported that central blood pressure and arterial stiffness are associated with cardiovascular outcomes. This trial aims to compare the efficacy of combination of calcium channel blocker (CCB) or thiazide diuretic with an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). -

Low Dose Combinations in the Treatment of Hypertension: Theory and Practice

Journal of Human Hypertension (1999) 13, 707–710 1999 Stockton Press. All rights reserved 0950-9240/99 $15.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/jhh ORIGINAL ARTICLE Low dose combinations in the treatment of hypertension: theory and practice NM Kaplan University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, TX 75235–8899, USA The recent evolution of drug therapy for hypertension combination with other agents. Such low-dose diuretic has primarily focused on new agents but there has been combinations are rational and their use will almost cer- a renewed interest in the use of low doses of diuretic in tainly increase. Keywords: drug therapy; hypertension; diuretics; low dose combinations Introduction cific coexisting conditions where certain drugs had favourable influences7 (Figure 2). The rationale for Major changes have occurred in the recommen- the first two paths is firmly based on the evidence dations for the initial treatment of hypertension. In from randomised controlled trials (RCTs), while the the US, the recommendations from the 1988 Joint third is more loosely based upon clinical experience National Committee report (JNC-IV) were to use any without the backing of RCTs. of four classes of drugs: diuretics, beta-blockers, The 1999 World Health Organization — Inter- angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), 8 1 national Society of Hypertension guidelines state or calcium antagonists (CAs). In the 1993 JNC-V that: ‘All available drug classes are suitable for the report, only diuretics or beta-blockers were rec- initiation and maintenance of antihypertensive ther- ommended since these were the only drugs that had apy’ but then provide a number of factors that influ- been tested in large-scale randomised controlled ence the choice, leading to a similar list of compel- trials (RCTs) and thereby shown to reduce cardio- 2 ling indications for specific drugs as provided in the vascular morbidity and mortality. -

Diuretic Treatment of Hypertension

HYPERTENSION Diuretic Treatment of Hypertension 1 3 EHUD GROSSMAN, MD FABIO ANGELI, MD cerebrovascular disease, combination 2 4 PAOLO VERDECCHIA, MD, FACC, FAHA, FESC GIANPAOLO REBOLDI, MD, PHD, MSC 1 therapy of a diuretic (indapamide) and ARI SHAMISS, MD ACE inhibitor (perindopril) reduced the risk of stroke by 43% compared with pla- cebo. Perindopril alone, despite lowering systolic BP by 5 mmHg, decreased stroke lthough thiazide and thiazide-like multiple-drug combinations in patients risk only by a nonsignificant 5%. diuretics are indispensable drugs in with resistant hypertension. The main Several studies attested to the supe- A fi the treatment of hypertension, their argument that will be discussed is the rior ef cacy of diuretic therapy over other role as first-line or even second-line drugs place of diuretics as first-line drugs or add- antihypertensive agents in reducing the is a provoking debate. on drugs in the context of the available risk for stroke (4–6,8,10,11). In the Sec- The European Society of Cardiology/ antihypertensive armamentarium. ond Australian National Blood Pressure European Society of Hypertension (ESC/ The pro side of the controversy will Study (ANBP2) (10), fatal stroke occurred ESH) guidelines recommend that thiazide argue that diuretics should remain the two times more in patients treated with an diuretics should be considered as suitable preferred drugs for initial treatment in ACE inhibitor than in patients treated as b-blockers, calcium antagonists, ACE many hypertensive patients, whereas the with a diuretic. In the Antihypertensive inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor cons side will contend that emerging and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent blockers for the initiation and mainte- evidence from outcome-based studies is Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) (4,5), chlor- nance of antihypertensive treatment (1). -

Clinical Pharmacology in Diuretic Use

NephropharmacologyCJASN ePress. Published on April 1, 2019 as doi: 10.2215/CJN.09630818 for the Clinician Clinical Pharmacology in Diuretic Use David H. Ellison Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: ccc–ccc, 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.09630818 Diuretics are among the most commonly prescribed Gastrointestinal Absorption of Diuretics drugs and, although effective, they are often used to The normal metabolism of loop diuretics is shown in treat patients at substantial risk for complications, Figure 2A. Furosemide, bumetanide, and torsemide are Departments of making it especially important to understand and absorbed relatively quickly after oral administration Medicine and appreciate their pharmacokinetics and pharmacody- (see Figure 2B), reaching peak concentrations within Physiology and – Pharmacology, namics (see recent review by Keller and Hann [1]). 0.5 2 hours (3,4); when administered intravenously, Oregon Health & Although the available diuretic drugs possess distinc- their effects are nearly instantaneous. The oral bioavail- Science University, tive pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic proper- ability of bumetanide and torsemide typically exceeds Portland, Oregon; and ties that affect both response and potential for adverse 80%, whereas that of furosemide is substantially lower, Renal Section, at approximately 50% (see Table 2) (5). Although the t Veterans Affairs effects, many clinicians use them in a stereotyped 1/2 Portland Health Care manner, reducing effectiveness and potentially in- of furosemide is short, its duration of action is longer System, Portland, creasing side effects (common diuretic side effects are when administered orally, as its gastrointestinal Oregon t listed in Table 1). Diuretics have many uses, but this absorption may be slower than its elimination 1/2.