The Guernsey Guns by Simon Hamon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valuing the Heritage of the Channel Islands

Valuing the Heritage of the Channel Islands Kate Clark Kate Clark Associates Heritage policy, practice & planning Elizabeth Castle, Jersey Valuing the Heritage of the Channel Islands An initial assessment against World Heritage Site criteria and Public Value criteria Kate Clark Kate Clark Associates For Jersey Heritage August 2008. List of Contents Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Summary Recommendations 8 Recommendation One: Do more to capture the value of Jersey’s Heritage Recommendation Two: Explore a World Heritage bid for the Channel Islands Chapter One - Valuing heritage 11 1.1 Gathering data about heritage 1.2 Research into the value of heritage 1.3 Public value Chapter Two – Initial assessment of the heritage of the Channel Islands 19 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Geography and politics 2.3 Brief history 2.4 Historic environment 2.5 Intangible heritage 2.6 Heritage management in the Channel Islands 2.7 Issues Chapter Three – capturing the value of heritage in the Channel Islands 33 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Intrinsic value 3.3 Instrumental benefits 3.4 Institutional values 3.5 Recommendations 4 Chapter Four – A world heritage site bid for the Channel Islands 37 4.0 Introduction 4.1 World heritage designation 4.2 The UK tentative list 4.3 The UK policy review 4.4 A CI nomination? 4.5 Assessment against World Heritage Criteria 4.6 Management criteria 4.7 Recommendations Conclusions 51 Appendix One – Jersey’s fortifications 53 A 1.1 Historic fortifications A 1.2 A brief history of fortification in Jersey A 1.3 Fortification sites A 1.4 Brief for further work Appendix Two – the UK Tentative List 67 Appendix Three – World Heritage Sites that are fortifications 71 Appendix Four – assessment of La Cotte de St Brelade 73 Appendix Five – brief for this project 75 Bibliography 77 5 Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the very kind support, enthusiasm, time and hospitality of John Mesch and his colleagues of the Société Jersiase, including Dr John Renouf and John Stratford. -

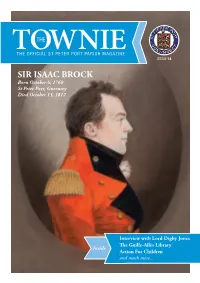

SIR ISAAC BROCK Born October 6, 1769 St Peter Port, Guernsey Died October 13, 1812

ISSUE 14 SIR ISAAC BROCK Born October 6, 1769 St Peter Port, Guernsey Died October 13, 1812 Interview with Lord Digby Jones The Guille-Allès Library Inside Action For Children and much more... New Honda Mid-size Range BF40/50/80/100 Ready for the next adventure Call 726829 for more information MARINE ENGINEERS & SUPPLIERS Email [email protected] Castle Emplacement St Peter Port Over 50 years of innovation, testing, re ning and testing again makes our marine technology the very best it can be. Delivering more power and better fuel economy with a new lightweight design, a world of adventure awaits with these outstanding 4-stroke engines. ENGINEERING FORLife For more information call: xxxx xxxxxx or visit: www.honda.co.uk/marine the time they have been in office. The duties which go with the position are not onerous. Each Douzenier should attend the meeting held on the FOREWORD last Monday of each month, they must be ready to attend the election of Jurats (10 members must attend); they should attend events during the year within St Peter Port when the Douzaine is seen by the Island, such as Remembrance Sunday ithout the articles you kindly produce and Liberation Day. Most Douzeniers are on there would be no issue. Thank you Committees which may take a little time up per also to our readers, who we hope will year - other than that there is little else which is enjoyW reading the contents of this Issue 14 of mandatory - however, if you want to carve out a The Townie. job there is plenty which can be done around the Parish, it’s not flashy and the work is sometimes In November there will be a Parish meeting - it has hard, but it is rewarding. -

Sainte Apolline's Chapel St. Saviour's, Guernsey Conservation Plan

Sainte Apolline's Chapel St. Saviour's, Guernsey Conservation Plan DRAFT Ref: 53511.03 December 2003 Wessex Archaeology Ste Apolline’s Chapel St Saviour’s Parish Guernsey Conservation Plan DRAFT Prepared for: States of Guernsey Heritage Committee Castle Cornet St Peter Port Guernsey GY1 1AU By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park Salisbury Wiltshire SP4 6EB In partnership with Carden & Godfrey Architects Environmental Design Associates Ltd AVN Conservation Consultancy & Dr John Mitchell Reference: 53511.03 18th December 2003 © The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited 2003 all rights reserved The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Ste Apolline’s Chapel, St Saviour’s Parish, Guernsey Conservation Plan CONTENTS CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION.................................................................................1 1.1 Project Background ..........................................................................................1 1.2 Aims of the Conservation and Management Plan..........................................1 1.3 Methods..............................................................................................................2 CHAPTER 2:UNDERSTANDING .............................................................................7 2.1 Site Location......................................................................................................7 2.2 Development of the Chapel ..............................................................................7 2.3 The Condition of the -

Uk & the Channel Island S

Preparation for D-Day D-Day is one of the most remembered campaigns of the Second World War. The operation involved troops from Britain, the United States, Canada and several other countries. On 6 June 1944, the Allied forces sailed toiled on various elements of the campaign, NETHERLANDS across the English Channel to begin their from providing safe harbours for the Newday Offices campaign to gain victory against the travelling fleet to ensuring that fuel would Jansbuitensingel 30 German army. Planning the invasion was an be in plentiful supply. An array of sites 6811 AE, Arnhem, NL +31 (0)85-3309090 enormous undertaking. linked to the planning, preparation and Ecstatic crowds greet British Officerrs from the Liberating British Force. ©Guernsey Museum implementation of D-Day are located across Often overlooked, planning the invasion BELGIUM Britain. Rue de Stassart 131 (codenamed Operation Overlord) was a The Channel Islands, from 1050 Brussels, BE mammoth task. A vast army of workers +32 (0) 485 136 833 occupation to liberation liberationroute.com When it became clear that the Islands would be JURRIAAN DE MOL, occupied, the population faced the traumatic decision Director Netherlands to leave their homes and move to England, divide their [email protected] +31 (0) 6 54388386 family by evacuating only their children or to remain together living under German rule. JOËL STOPPELS, Project manager Those choosing to remain experienced Mainly used for hunting and training [email protected] five hard and hungry years living under exercises, these smaller Islands remained +31 (0) 6 36 33 53 70 stifling rules and regulations. -

Christmas 1917 Must Have Been One of the Saddest Seasons of Goodwill

Guernsey’s Lost Generation By Liz Walton The impact of the German Occupation on Guernsey’s way of life has been the subject of many books, films and documentaries in recent years. However the scale of change brought about by the previous war has largely been overlooked. The First World War, or the Great War for Civilisation as it was then called, ended only twenty years before the Second World War began. Memories of its horrors were probably still too fresh in the minds of the men returning to the island for them to want to write or talk about it in the inter-war years, and since then, the more recent conflict has largely replaced its predecessor as a subject for study. This is due at least in part to its greater accessibility, as it is still within the living memory of many islanders, while very few survivors of the 1914-18 war remain. Also in the Second World War, all islanders rather than just the fighting men were brought face to face with the enemy, and suffered bombing, hardship and deprivation. This focus on the more recent conflict at the expense of the earlier one means that nowadays many islanders are not aware of the fact that Guernsey, like many other communities, effectively lost a generation of young men in one year, and with this loss a way of life was changed for ever. By the time that war broke out, in August 1914, Guernsey’s population had doubled compared with a hundred years earlier1, reaching a total of approximately 40,000. -

![Channel Islands Guernsey[2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8151/channel-islands-guernsey-2-2868151.webp)

Channel Islands Guernsey[2]

Premium UK 12-15 Hanger Green, London W5 3EL, U.K. Tel: +44 (0)20 8601 2424 Fax: +44 (0)20 8991 2483 Email: [email protected] www.spectra-dmc.com Explore Channel Islands – Guernsey Hotels The Old Government House Hotel & Spa 5* The OGH (as it is affectionately known) was originally the official residence of the island's Governor. Now a beautiful and luxurious hotel, it has been extensively redecorated with sumptuous bedrooms and stylishly appointed function rooms. The hotel's own Spa offers a wide range of Darphin health and beauty treatments plus an outdoor pool, gym, spa pool, sauna and steam room. Five-minute walk from the lovely and historic St Peter Port Harbour, it's perfect for a luxury break and offers a wide range of excellent value packages throughout the year. Bedrooms: 62 Suites: 3 Fermain Valley Hotel 4* Peaceful and secluded yet conveniently situated just 5 minutes from Guernsey’s charming harbour capital, St Peter Port, the 4 star Fermain Valley Hotel is an ideal location for a relaxing break. Set in over 6 acres of beautifully landscaped gardens; the hotel has 45 exquisitely decorated bedrooms all unique (some enjoy private balconies) and designed with your comfort in mind with a complimentary decanter of sherry, luxury toiletries, Sky TV and a turndown service. The hotel has two restaurants, Ocean which offers fresh seafood and a beautiful terrace area offering stunning views down the valley to the sea and The Rock Garden Steakhouse, a vibrant cocktail bar serving steaks from around the globe. Bedrooms: 45 Spectra Travel England Ltd. -

Library Catalogue 2019

LA SOCIÉTÉ GUERNESIAISE LIBRARY CATALOGUE Compiled by David Le Conte, Librarian and Archivist, 2016-2019 Please note: • Items are listed and shelved generally in chronological order by date of publication. • The items listed here are held at the headquarters of La Société Guernesiaise at Candie Gardens. • Items relating to specific Sections of La Société are not listed here, but are generally held at The Russels or by those Sections (including: Archaeology, Astronomy, Botany, Family History, Geology, Language, Marine Biology, Nature, Ornithology). • Archived items are held at the Island Archives and are listed separately. • For queries and more detailed descriptions of items please contact the Librarian and Archivist through La Société Guernesiaise ([email protected]). Shelves: Guernsey Channel Islands German Occupation Alderney Sark Herm, Jethou and Lihou Jersey Family History La Société Guernesiaise Language Maps Normandy Miscellaneous GUERNSEY Title Author(s) Publisher Date Island of Guernsey F Grose c1770 Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, The History of the Island of Guernsey Berry, William 1815 and Brown A Treatise on the History, Laws and Warburton, Mr Dumaresq & Mauger 1822 Jacob's Annals of Guernsey, Part I Jacob, J John Jacob 1830 Rimes Guernesiais Un Câtelain [Métivier, G] Simpkin, Marshall et Cie. 1831 Memoir of the Late Colonel William Le 1836 Messurier Tupper The History of Guernsey Duncan, Jonathan Longman, Brown, Green & 1841 Longman, Brown, Green & The History of Guernsey Duncan, Jonathan 1841 Longmans Traité de -

Channel Islands Explorer – Jersey & Guernsey 7 Days/ 6 Nights This

Channel Islands Explorer – Jersey & Guernsey 7 Days/ 6 Nights This Channel Islands Explorer tour gives an opportunity to discover the neighbouring islands of Jersey & Guernsey. The warm climate may be the same, but the way of life is totally different. Jersey, the popular holiday destination, is an island of beautiful landscapes, with sandy beaches and towering cliffs. Not only does Jersey offer a variety of outdoor adventures but there is also a wealth of sites to discover including the St Elizabeth Church and the Jersey War Tunnels. In Guernsey, discover St Peter’s Port, a busy port with cobbled streets and one of Europe’s prettiest harbour towns. Includes ● Accommodation- 3 nights on Jersey & 3 nights on Guernsey, breakfast daily ● Private transfers between airport or port and your hotel in Jersey & Guernsey ● Ferry crossing between Jersey & Guernsey with Condor Ferries ● Full day Island Tours on Jersey and Guernsey with guide ● Full day tour to Sark with transfers between hotel & port and return ferry crossing between Guernsey & Sark ● Entrance to Jersey War Tunnels ● All local taxes and charges Itinerary Day 1 Jersey Make your way by either air or ferry to the Jersey. On arrival you will be met and transferred to your hotel for 3 nights. Explore the wonderful cafes and restaurants in St Helier for a great choice of dining options. Day 2 Jersey After breakfast enjoy a breath taking Island tour. Your knowledgeable driver/guide will take you to the popular sights and attractions of Jersey including the beautiful bays of St Brelade and St Ouen, the Corbiere Lighthouse and the charming village of St Aubin. -

St. Peter Port Guernsey, Channel Islands

ST. PETER PORT GUERNSEY, CHANNEL ISLANDS Discover St. Peter Port and Guernsey, The Sunshine Island. Explore the charms of St. Peter Port on the island of Guernsey, a British territory off the coast of France. Overlooking a pretty harbor, the town is full of brightly painted houses, terraced gardens and fun shopping streets where locals welcome sunny days. Fishing, flowers and dairy farming are still the main ways of life here. Ramble alongside cliffs and down bucolic paths while enjoying the peaceful atmosphere of The Sunshine Island. LOCAL CUISINE SHOPPING Guernsey islanders are Shop the High Street and passionate about food. the Old Quarter in St. Peter Favorite meals are warming Port for a lively time. Clothes, and traditional. accessories and jewelry from major UK and French brands Bean jar, a slow-cooked butter intermix with local creations. bean dish, is the ultimate Most shops are independently local comfort food, served owned here. with carrots, onions and a little ham for flavor. Try it with a side of gâche, the For a traditional souvenir, ubiquitous fruit bread of currants and orange. From search out an iconic milk the sea, order ormer casserole, a baked pork and can. Guernsey cows produce abalone meal, or island crab patties with the local wonderful dairy and the large, curved steel cans butter and a little lemon. make for a playful decor element at home. Guernseymen drink lots of sloe gin, a potent spirit Guernsey sweaters, called jumpers, are a steadfast made of local sloe or blackthorn fruit. Milk punch, souvenir, too. Warm knits in delightful patterns are made with milk and rum, is also popular. -

Castle Carey a Rare Opportunity to Acquire One of the Most Prestigious Private Residences in the Channel Islands

Castle Carey A rare opportunity to acquire one of the most prestigious private residences in the Channel Islands BLENDING ELEGANCE AND STATURE ON A MAGNIFICENT SCALE, THIS LANDMARK PROPERTY OCCUPIES A COMMANDING AND PRIME LOCATION ABOVE Guernsey’s HISTORIC TOWN OF ST PETER PORT. THE IMPRESSIVE HOUSE AND ITS EXTENSIVE SOUTH FACING GARDENS OFFER SHELTERED SECLUSION WHILST TAKING FULL ADVANTAGE OF PANORAMIC VIEWS, PARTICULARLY FROM THE PRINCIPAL ROOMS, ACROSS THE BUSY HARBOUR TOWARDS NEIGHBOURING ISLAnds – A BOATING PARADISE FOR SAILORS AND ONLOOKERS ALIKE. Part of Castle Carey’s panoramic views showing the neighbouring islands of Herm, Jethou, Sark and Jersey on the horizon. A landmark property for nearly 200 years Castle Carey was completed c1840 during the Gothic revival period with classic Regency style influenced C by Adamesque features. It is thought to have been designed by the acclaimed architect, John Wilson, who designed Elizabeth College and St James Concert Hall, both of which can be seen from Castle Carey. A sympathetic Victorian extension later enhanced the stately accommodation, yet the grandeur of the principal rooms is balanced with the charm of a comfortable and much cherished family home. Little wonder the passing generations have seen only five discerning owners since the Carey family. Indeed, this distinctive property was briefly the ambassadorial residence of the royal appointed Lieutenant Governor of the Bailiwick of Guernsey and hosted Queen Victoria and Prince Albert during their visit to Guernsey in 1859. Later, in 1862, the Duke of Cambridge stayed at the castle and the Royal Standard was flown to mark his stay. Castle Carey is mentioned by name in Victor Hugo’s famous An ancient map pin points Castle Carey as a notable building. -

Channel Islands, Island Hopping Holiday

Channel Islands, Island Hopping Holiday Tour Style: Island Hopping Destinations: Channel Islands & England Trip code: GYLDW Trip Walking Grade: 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Our Channel Island Hopping visits the islands of Guernsey, Alderney, Sark and Herm. These stunning islands enjoy a great climate and a relaxed way of life. The islands all have their own unique identities, which you can explore as you walk along their stunning coastlines. Based near the seafront at St Peter Port on Guernsey for your holiday, we include an exciting day flight to walk and discover Alderney and boat trips to walk and discover both Sark and Herm. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Full Board en-suite accommodation • Experienced HF Holidays Walking Leader • All transport to and from the walks • All inter-island flights and ferries • Transfers to and from Guernsey airport • "With flight" holidays include return flights from London and hotel transfers www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Step back in time on Sark with its car-free lanes and stunning clifftop paths • Sail to Herm and explore its unique identity • Nature lovers and history buffs will love Alderney as we fly for the day to walk and enjoy all it offers • Stunning coastal walks on Guernsey TRIP SUITABILITY This Guided Island Hopping /Hiking Trail is graded 3 which involves walks/hikes on well-defined paths, though often in hilly or upland areas, or along rugged coastal footpaths. These may be rough and steep in sections, and often with many steps, so a good level of fitness is required. -

10.00AM – LOTS 1 - 250 Plates

AUCTIONEERS AND VALUERS OF FINE ART AND ANTIQUES Auction Rooms, 40 Cornet Street, St Peter Port, GY1 1LF Telephone: 01481 722700 Fax: 01481 723306 E-mail: [email protected] ORDER OF SALE BY PUBLIC AUCTION TUESDAY 22 ND MARCH 2016 – 10.00AM & 1.00PM 10.00AM – LOTS 1 - 250 plates. 42 A set of three Heppell & Co. purple malachite £40/60 1 Two small cast iron fire backs. £10/20 glass fish water jugs. 2 A large mustard glazed garden pot + others £20/30 43 A large quantity of various vintage coins. £30/40 (3). 44 An Indian Kashmiri stationary box plus a £30/40 3 A large blue glazed garden pot + other (2). £20/30 quantity of similar boxes (9). 4 An Indian square carved red sandstone low £50/60 45 A quantity of various Victorian purple £20/30 table or stand. malachite glass (8). 5 Three framed Toplis book plates/prints + other £70/90 46 Three Villeroy & Boch drinking glasses + £10/20 (4). glass rose vase (4). 6 Three Ltd edition prints of Bath plus Salisbury £25/30 47 A Meissen style floral porcelain charger. £30/40 Cathedral watercolour (4). 48 A pair of blue glazed & gilt oriental vases. £20/30 7 M. Parsons - oil on board, 'Wishing Well, £30/50 49 Four pieces of Wedgwood, teapot, biscuit £25/30 Water Lanes, Guernsey' barrel etc (4). 8 A pair of Victorian spelter figures. £20/30 50 A pair of brass duck bookends. £10/20 9 A vintage bagatelle board. £20/30 51 Pair of Victorian opaque turquoise glass vases, £20/30 10 HB book, Duncan 'The History of Guernsey' £50/70 comport, bowl (4).