Soft Tissue Tumours: the Surgical Pathologist's Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparison of Imaging Modalities for the Diagnosis of Osteomyelitis

A comparison of imaging modalities for the diagnosis of osteomyelitis Brandon J. Smith1, Grant S. Buchanan2, Franklin D. Shuler2 Author Affiliations: 1. Joan C Edwards School of Medicine, Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 2. Marshall University The authors have no financial disclosures to declare and no conflicts of interest to report. Corresponding Author: Brandon J. Smith Marshall University Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine Huntington, West Virginia Email: [email protected] Abstract Osteomyelitis is an increasingly common pathology that often poses a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. Accurate and timely diagnosis is critical to preventing complications that can result in the loss of life or limb. In addition to history, physical exam, and laboratory studies, diagnostic imaging plays an essential role in the diagnostic process. This narrative review article discusses various imaging modalities employed to diagnose osteomyelitis: plain films, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound, bone scintigraphy, and positron emission tomography (PET). Articles were obtained from PubMed and screened for relevance to the topic of diagnostic imaging for osteomyelitis. The authors conclude that plain films are an appropriate first step, as they may reveal osteolytic changes and can help rule out alternative pathology. MRI is often the most appropriate second study, as it is highly sensitive and can detect bone marrow changes within days of an infection. Other studies such as CT, ultrasound, and bone scintigraphy may be useful in patients who cannot undergo MRI. CT is useful for identifying necrotic bone in chronic infections. Ultrasound may be useful in children or those with sickle-cell disease. Bone scintigraphy is particularly useful for vertebral osteomyelitis. -

Soft Tissue Tumor Pathology: New Diagnostic Immunohistochemical Markers Leona A

S EMINARS IN D IAGNOSTIC P ATHOLOGY ] (2015) ]]]– ]]] Available online at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/semdp Soft tissue tumor pathology: New diagnostic immunohistochemical markers Leona A. Doyle, MD Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 75 Francis St, Boston, Massachusetts article info abstract Keywords: Recent insights into the pathogenesis of various soft tissue tumors, along with the Soft tissue identification of recurrent molecular alterations characteristic of specific tumor types, Tumor have resulted in the development of many diagnostically useful immunohistochemical Sarcoma markers. In some cases, expression of these markers is significantly associated with Immunohistochemistry distinctive clinical and histologic features, which may impart prognostic or predictive Molecular genetics information. This review outlines new diagnostic immunohistochemical markers in soft tissue tumor pathology, emphasizing their utility in clinical practice and potential pitfalls, molecular correlates and clinical associations. & 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction shows MYC amplification. Finally, so-called lineage specific markers, which tend to show nuclear staining and in general fi Over the last 10 years, many novel immunohistochemical are not strictly speci c to a given lineage, have also emerged markers for use in the evaluation of soft tissue tumors have as useful markers, not only in soft tissue pathology but also been described. This has largely been due to new insights -

Bone & Soft Tissue Pathology Fellowship

Bone & Soft Tissue Pathology Fellowship The Department of Pathology at Memorial Availability: July 2023 Sloan Kettering Cancer Center offers a one- year fellowship training program in bone and Number of Positions: One soft tissue pathology. The fellowship begins on Length of Program: One Year July 1st and ends on June 30th the following year. All fellows should have completed Deadline: August 1, for appoint- residency training in anatomic pathology and ments beginning 2 years later (ie. be certified (or eligible for certification) by 8/1/2021 for start date 7/1/2023). the American Board of Pathology. Early application is acceptable because completed applications may be During the sub-specialty fellowship year, the considered on a rolling basis. fellow will have the opportunity to study our large volume of quality in-house and submitted How to Apply: Apply Online material, departmental consultation case Only complete applications will material, as well as recommended reading of be reviewed. Once applicants have literature to achieve adequate competence submitted their applications, they will in the pathologic diagnosis, staging, and need to send the following documents: prognostication of a wide variety of bone and • Three letters of recommendation from soft tissue tumors. In addition, the fellow an institution in which the applicant will have the opportunity to perform clinico- has trained. Letters should be pathologic and molecular correlations. addressed to Dr. Ronald Ghossein, the The fellow will serve as a consultant to the program director. Please request letter oncologic pathology fellows in the orientation, writers add the following line after gross dissection and morphologic evaluation the heading (RE: Candidate’s Name, of bone and soft tissue specimens. -

Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone

bb5_1.qxd 13.9.2006 14:05 Page 3 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours WHO OMS International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone Edited by Christopher D.M. Fletcher K. Krishnan Unni Fredrik Mertens IARCPress Lyon, 2002 bb5_1.qxd 13.9.2006 14:05 Page 4 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Series Editors Paul Kleihues, M.D. Leslie H. Sobin, M.D. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone Editors Christopher D.M. Fletcher, M.D. K. Krishnan Unni, M.D. Fredrik Mertens, M.D. Coordinating Editor Wojciech Biernat, M.D. Layout Lauren A. Hunter Illustrations Lauren A. Hunter Georges Mollon Printed by LIPS 69009 Lyon, France Publisher IARCPress International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) 69008 Lyon, France bb5_1.qxd 13.9.2006 14:05 Page 5 This volume was produced in collaboration with the International Academy of Pathology (IAP) The WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone presented in this book reflects the views of a Working Group that convened for an Editorial and Consensus Conference in Lyon, France, April 24-28, 2002. Members of the Working Group are indicated in the List of Contributors on page 369. bb5_1.qxd 22.9.2006 9:03 Page 6 Published by IARC Press, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 150 cours Albert Thomas, F-69008 Lyon, France © International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2002, reprinted 2006 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. -

Soft Tissue Pathology

A CME Teaching Activity 2021 Classic Lectures in Pathology: What You Need to Know: Soft Tissue Pathology Release Date: January 15, 2021 | 19.75 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)TM About This CME Teaching Activity Educational Objectives This CME Activity offers a practical review of soft tissue and bone At the completion of this CME teaching activity, you should be pathology combining basic to advanced techniques, pearls and pitfalls able to: to pathologic diagnosis and case reviews. • Develop an approach to common morphologic patterns seen in Target Audience soft tissue tumors. This CME activity is intended and designed to educate pathologists. • Discuss the ancillary diagnostic approach to difficult soft tissue Scientific Sponsor tumors including immunohistochemistry, molecular, and genetic diagnostic tests. Educational Symposia • Discuss bone-forming and cartilage-forming soft tissue tumors, as Accreditation well as sarcomas that may occasionally produce matrix. Physicians: Educational Symposia is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide • Discuss the differential diagnosis of a spindle cell sarcoma with continuing medical education for physicians. herringbone/fascicular growth. Educational Symposia designates this enduring material for a maximum • Develop an integrated approach to the most common bone of 19.75 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)TM. Physicians should claim only tumors seen by practicing pathologists. the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. • Explain ancillary diagnostic techniques including All activity participants are required to take a written or online test in immunohistochemistry and molecular diagnostics in the order to be awarded credit. (Exam materials, if ordered, will be sent approach to difficult soft tissue tumors. -

Soft Tissue Pathology: a One-On-One Tutorial with Purchase of Entire Set Soft Tissue Pathology: a One-On-One Tutorial ENTIRE SERIES

About This CME Teaching Activity Target Audience CME This seminar is designed to provide a practical yet This CME activity is primarily intended and comprehensive review of soft tissue tumor pathology. designed to educate pathologists. Anytime, Anywhere A pattern-based approach to diagnosis, including an emphasis on differential diagnosis, as well as the use of ancillary diagnostic methods (especially docmedED.com immunohistochemistry) will be discussed. 5% ACCESS YOUR CME Better & Faster Than Ever Before! Faster Site Speed Scientific Sponsor Order Online & Save Order Educational Symposia Improved Searchability code above the promo by providing ONE edusymp.com | Accreditation Preview Lectures FREE HOUR Physicians: Educational Symposia is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical $20 Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians. • Lectures presented by Expert Series with top educators and speakers Educational Symposia designates this enduring material for a maximum of 16.0 AMA PRA Category 1 in their specialty. Credit(s)TM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in • Professionally produced Jason L. Hornick, M.D., Ph.D. the activity. and developed All activity participants are required to take a written or online test in order to be awarded credit. (Exam • Over 1,300 CME hours, materials, if ordered, will be sent with your order.) All course participants will also have the opportunity to with more added every day! critically evaluate the program as it relates to practice relevance and educational objectives. AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)TM for this activity may be claimed until May 14, 2022. docmedED.com EXPERIENCE TODAY! This CME activity was planned and produced by Educational Symposia, Soft Tissue a leader in continuing medical education since 1975. -

Immunohistochemistry of Soft Tissue Tumors. an Update

1999; Vol. 32, P3 Recent advances and controversies in soft tissue pathology predictive, regardless of histological features (provided the correct — Merck C, Angervall L, Kindblom LG et al. Myxofibrosarcoma - a malignant soft histological diagnosis has been madel). tissue tumor of fibroblastic-histiocytic origin; a clinicopathologic and prognostic Because of the current problems in grading sarcomas, we study of 110 cases using multivariate analysis. Acts Pethol Microbial Scand 1983; A(Suppl. 282). believe that the grading criteria should be revised for each type of — Myrhe-Jensen 0, Hftgh J, Ostergaard SE St al. Histopathological gradingof soft soft tissue tumor. This sounds like a formidable task, particularly in tissue tumors: prognostic significance in a prospective study of278 consecutive view of 50 different sarcoma diagnoses and the relative rarity of cases. J Pathol 1991; 163: 19-24. sarcomas. Moreover, the study of each specific type of sarcoma — Trolani M, Contesso G, Coindre et. al. Soft tissue sarcomas of adults; study of needs to be subjected to multivariate statistical analysis with simul- pathological prognostic variables and definition of a histopathological grading taneous consideration of histological, clinical and treatment factors system. ~d Cancer 1984; 33: 37-42. in order to elucidate which of these are independent prognostic fac- tors. The literature is replete with studies in which only a few fac- tors have been examined with regard to prognosis while completely ignoring others (i.e., the design of many studies has been flawed). Collecting a sufficient number of rare cases to allow statistical Immunohistochemistry analysis could be overcome by interinstitutional collaboration and also through metaanalysis of appropriate cases. -

Bone Biopsy.Pdf

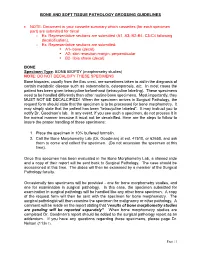

BONE AND SOFT TISSUE PATHOLOGY GROSSING GUIDELINES NOTE: Document in your cassette summary which cassettes (for each specimen part) are submitted for decal o Ex: Representative sections are submitted (A1, A3; B2-B4; C3-C4 following decalcification). o Ex: Representative sections are submitted: . A1- bone (decal) . A2- skin resection margin, perpendicular . B2- tibia shave (decal) BONE Specimen Type: BONE BIOPSY (morphometry studies) NOTE: DO NOT DECALCIFY THESE SPECIMENS Bone biopsies, usually from the iliac crest, are sometimes taken to aid in the diagnosis of certain metabolic disease such as osteomalacia, osteoporosis, etc. In most cases the patient has been given tetracycline beforehand (tetracycline labeling). These specimens need to be handled differently than other routine bone specimens. Most importantly, they MUST NOT BE DECALCIFIED! When the specimen arrives in Surgical Pathology, the request form should state that the specimen is to be processed for bone morphometry. It may simply state that the patient has been “tetracycline labeled”. It may instruct you to notify Dr. Goodman’s lab. In any event, if you see such a specimen, do not process it in the normal manner because it must not be decalcified. Here are the steps to follow to insure the proper handling of these specimens: 1. Place the specimen in 10% buffered formalin. 2. Call the Bone Morphometry Lab (Dr. Goodman) at ext. 47510, or 62650, and ask them to come and collect the specimen. (Do not accession the specimen at this time). Once this specimen has been evaluated in the Bone Morphometry Lab, a stained slide and a copy of their report will be sent back to Surgical Pathology. -

Bone and Soft Tissue Pathology Specimens and 127 Surgicals (Biopsies and Resections)

ANNUAL MEETING ABSTRACTS 11A the morphologic spectrum and etiology of DAD encountered during adult autopsy in (non-EWSR1) NR4A3 gene fusions (TAF15, TCF12) showed distinctive plasmacytoid an inner city teaching hospital. The diagnostic utility of post mortem lung culture was / rhabdoid morphology, with increased cellularity, cytologic atypia and high mitotic also evaluated. counts. Follow-up showed that only 1 of 16 patients with EWSR1-rearranged tumors Design: A retrospective study was performed on all adult autopsies from July 2010 to died of disease, in contrast to 3 of 7 (43%) patients with TAF15–rearranged tumors. July 2013 with fi nal histopathologic diagnosis of DAD. The histopathological features Conclusions: In conclusion, EMCs with variant NR4A3 gene fusions show a higher of DAD were re-evaluated by one autopsy pathologist and one pathology resident, incidence of rhabdoid phenotype, high grade morphology and a more aggressive based on the duration (exudative or proliferative phase), severity (bilateral/unilateral; outcome compared to the more common EWSR1-NR4A3 positive tumors. Furthermore, focal/extensive) and pattern (classical vs. acute fi brinous and organizing pneumonia as EWSR1 FISH break-apart assay is the preferred ancillary test to confi rm diagnosis aka AFOP). Clinical history, pre and post mortem laboratory investigations, including of EMC, tumors with variant NR4A3 gene fusions remain under-recognized and often postmortem lung culture (for bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi and virus) were reviewed misdiagnosed. FISH assay for NR4A3 rearrangements recognizes >95% of EMCs and to elucidate etiology. should be an additional tool in EWSR1-negative tumors. Results: 36 (16.2 %) cases showed histopathologic features of DAD out of 222 adult autopsies in the three year study period. -

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Benign Soft Tissue Neoplasms in Adults

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Benign Soft Tissue Neoplasms in Adults Eric A. Walker, MDa,b,*, Michael E. Fenton, MDc, Joel S. Salesky, MDc, Mark D. Murphey, MDb,c,d KEYWORDS Soft tissue tumor Benign MR imaging Soft tissue neoplasm Benign soft tissue lesions outnumber their malig- tics. Fast-spin echo sequences in place of SE nant counterparts by a factor of 100:1.1,2 Many sequences can reduce scanning time and patient of these lesions are small and superficial and do motion artifacts. Gradient echo sequences can not lead to imaging evaluation or biopsy; so be useful for demonstrating hemosiderin with precise estimates are unavailable. Magnetic reso- “blooming” and also are subject to artifact caused nance (MR) imaging is the favored modality for by metal, hemorrhage, and air. Short tau inversion evaluation of soft tissue tumors and tumorlike recovery and chemical shift–selective fat saturation conditions because of its superior soft tissue T2W images increase sensitivity to abnormal tissue contrast, multiplanar imaging capability, and lack containing increased water content. However, in of radiation exposure. MR imaging is valuable for our opinion, these techniques also reduce infor- lesion detection, diagnosis, and staging. mation concerning various tissue consistencies When planning an MR imaging study for evalua- and should be used in the secondary, not the tion of a soft tissue lesion, at least 2 orthogonal primary, plane of imaging. The smallest diagnostic planes should be obtained. In our experience, field of view is preferable when evaluating these lesions are typically best evaluated in the axial lesions. plane, and this plane is usually the most familiar The use of intravenous contrast for lesion evalu- to radiologists. -

View Article

Annals of DIAGNOSTIC PATHOLOGY VOL 5, NO 4 AUGUST 2001 ORIGINAL ARTICLES Nodular Fasciitis of the External Ear Region: A Clinicopathologic Study of 50 Cases Lester D.R. Thompson, MD, Julie C. Fanburg-Smith, MD, and Bruce M. Wenig, MD Nodular fasciitis (NF), uncommon in the auricular area, is a benign reactive myofibroblastic proliferation that may be mistaken for a neoplastic proliferation. Fifty cases of NF of the auricular region were identified in the files of the Otorhinolaryngic-Head and Neck Tumor Registry of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. The patients included 22 females and 28 males, aged 1 to 76 years (mean, .(49 ؍ years). The patients usually presented clinically with a mass lesion (n 27.4 or (28 ؍ Five patients recalled antecedent trauma. The lesions were dermal (n ,in those cases where histologic determination was possible (11 ؍ subcutaneous (n ؍ measuring 1.9 cm on average. The majority of the lesions were circumscribed (n 38), composed of spindle-shaped to stellate myofibroblasts arranged in a storiform growth pattern, juxtaposed to hypocellular myxoid tissue-culture-like areas with extravasation of erythrocytes. Dense, keloid-like collagen and occasional giant cells .Mitotic figures (without atypical forms) were readily identifiable .(18 ؍ were seen (n By immunohistochemical staining, myofibroblasts were reactive with vimentin, ac- tins, and CD68. All patients had surgical excision. Four patients (9.3%) developed local recurrence and were alive and disease free at last follow-up. All patients with were alive or had died of unrelated causes, without evidence of (43 ؍ follow-up (n disease an average 13.4 years after diagnosis. -

Bone and Soft Tissue Pathology (37-109)

LABORATORY INVESTIGATION THE BASIC AND TRANSLATIONAL PATHOLOGY RESEARCH JOURNAL LI VOLUME 100 | SUPPLEMENT 1 | MARCH 2020 ABSTRACTS BONE AND SOFT TISSUE PATHOLOGY (37-109) LOS ANGELES CONVENTION CENTER FEBRUARY 29-MARCH 5, 2020 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 2020 ABSTRACTS | PLATFORM & POSTER PRESENTATIONS EDUCATION COMMITTEE Jason L. Hornick, Chair William C. Faquin Rhonda K. Yantiss, Chair, Abstract Review Board Yuri Fedoriw and Assignment Committee Karen Fritchie Laura W. Lamps, Chair, CME Subcommittee Lakshmi Priya Kunju Anna Marie Mulligan Steven D. Billings, Interactive Microscopy Subcommittee Rish K. Pai Raja R. Seethala, Short Course Coordinator David Papke, Pathologist-in-Training Ilan Weinreb, Subcommittee for Unique Live Course Offerings Vinita Parkash David B. Kaminsky (Ex-Officio) Carlos Parra-Herran Anil V. Parwani Zubair Baloch Rajiv M. Patel Daniel Brat Deepa T. Patil Ashley M. Cimino-Mathews Lynette M. Sholl James R. Cook Nicholas A. Zoumberos, Pathologist-in-Training Sarah Dry ABSTRACT REVIEW BOARD Benjamin Adam Billie Fyfe-Kirschner Michael Lee Natasha Rekhtman Narasimhan Agaram Giovanna Giannico Cheng-Han Lee Jordan Reynolds Rouba Ali-Fehmi Anthony Gill Madelyn Lew Michael Rivera Ghassan Allo Paula Ginter Zaibo Li Andres Roma Isabel Alvarado-Cabrero Tamara Giorgadze Faqian Li Avi Rosenberg Catalina Amador Purva Gopal Ying Li Esther Rossi Roberto Barrios Anuradha Gopalan Haiyan Liu Peter Sadow Rohit Bhargava Abha Goyal Xiuli Liu Steven Salvatore Jennifer Boland Rondell Graham Yen-Chun Liu Souzan Sanati Alain Borczuk Alejandro