Bone and Soft Tissue Pathology Diagnostic and Prognostic Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary for Narrative Writing

Periodontal Assessment and Treatment Planning Gingival description Color: o pink o erythematous o cyanotic o racial pigmentation o metallic pigmentation o uniformity Contour: o recession o clefts o enlarged papillae o cratered papillae o blunted papillae o highly rolled o bulbous o knife-edged o scalloped o stippled Consistency: o firm o edematous o hyperplastic o fibrotic Band of gingiva: o amount o quality o location o treatability Bleeding tendency: o sulcus base, lining o gingival margins Suppuration Sinus tract formation Pocket depths Pseudopockets Frena Pain Other pathology Dental Description Defective restorations: o overhangs o open contacts o poor contours Fractured cusps 1 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 Caries Deposits: o Type . plaque . calculus . stain . matera alba o Location . supragingival . subgingival o Severity . mild . moderate . severe Wear facets Percussion sensitivity Tooth vitality Attrition, erosion, abrasion Occlusal plane level Occlusion findings Furcations Mobility Fremitus Radiographic findings Film dates Crown:root ratio Amount of bone loss o horizontal; vertical o localized; generalized Root length and shape Overhangs Bulbous crowns Fenestrations Dehiscences Tooth resorption Retained root tips Impacted teeth Root proximities Tilted teeth Radiolucencies/opacities Etiologic factors Local: o plaque o calculus o overhangs 2 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 o orthodontic apparatus o open margins o open contacts o improper -

Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors Have Been Treated Separately

EPIDEMIOLOGY z Sarcomas are rare tumors compared to other BONE AND SOFT malignancies: 8,700 new sarcomas in 2001, with TISSUE TUMORS 4,400 deaths. z The incidence of sarcomas is around 3-4/100,000. z Slight male predominance (with some subtypes more common in women). z Majority of soft tissue tumors affect older adults, but important sub-groups occur predominantly or exclusively in children. z Incidence of benign soft tissue tumors not known, but Fabrizio Remotti MD probably outnumber malignant tumors 100:1. BONE AND SOFT TISSUE SOFT TISSUE TUMORS TUMORS z Traditionally bone and soft tissue tumors have been treated separately. z This separation will be maintained in the following presentation. z Soft tissue sarcomas will be treated first and the sarcomas of bone will follow. Nowhere in the picture….. DEFINITION Histological z Soft tissue pathology deals with tumors of the classification connective tissues. of soft tissue z The concept of soft tissue is understood broadly to tumors include non-osseous tumors of extremities, trunk wall, retroperitoneum and mediastinum, and head & neck. z Excluded (with a few exceptions) are organ specific tumors. 1 Histological ETIOLOGY classification of soft tissue tumors tumors z Oncogenic viruses introduce new genomic material in the cell, which encode for oncogenic proteins that disrupt the regulation of cellular proliferation. z Two DNA viruses have been linked to soft tissue sarcomas: – Human herpes virus 8 (HHV8) linked to Kaposi’s sarcoma – Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) linked to subtypes of leiomyosarcoma z In both instances the connection between viral infection and sarcoma is more common in immunosuppressed hosts. -

Advances in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Bone Sarcoma Therapy

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Advances in immune checkpoint inhibitors for bone sarcoma therapy. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3k40w8f4 Authors Thanindratarn, Pichaya Dean, Dylan C Nelson, Scott D et al. Publication Date 2019-04-01 DOI 10.1016/j.jbo.2019.100221 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of Bone Oncology 15 (2019) 100221 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Bone Oncology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jbo Review Article Advances in immune checkpoint inhibitors for bone sarcoma therapy T Pichaya Thanindratarna,b, Dylan C. Deana, Scott D. Nelsonc, Francis J. Horniceka, ⁎ Zhenfeng Duana, a Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Sarcoma Biology Laboratory, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, 615 Charles E. Young. Dr. South, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA b Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Chulabhorn hospital, HRH Princess Chulabhorn College of Medical Science, Bangkok, Thailand c Department of Pathology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Bone sarcomas are a collection of sporadic malignancies of mesenchymal origin. The most common subtypes Immune checkpoint include osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and chordoma. Despite the use of aggressive treatment Immunotherapy protocols consisting of extensive surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, outcomes have not sig- Bone sarcoma nificantly improved over the past few decades for osteosarcoma or Ewing sarcoma patients. In addition, chon- Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drosarcoma and chordoma are resistant to both chemotherapy and radiation therapy. There is, therefore, an Anti-CTLA-4 urgent need to elucidate which novel new therapies may affect bone sarcomas. -

A Rare Presentation of Benign Brenner Tumor of Ovary: a Case Report

International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology Periasamy S et al. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jul;7(7):2971-2974 www.ijrcog.org pISSN 2320-1770 | eISSN 2320-1789 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20182920 Case Report A rare presentation of benign Brenner tumor of ovary: a case report Sumathi Periasamy1, Subha Sivagami Sengodan2*, Devipriya1, Anbarasi Pandian2 1Department of Surgery, 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Government Mohan Kumaramangalam Medical College, Salem, Tamil Nadu, India Received: 17 April 2018 Accepted: 23 May 2018 *Correspondence: Dr. Subha Sivagami Sengodan, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Brenner tumors are rare ovarian tumors accounting for 2-3% of all ovarian neoplasms and about 2% of these tumors are borderline (proliferating) or malignant. These tumors are commonly seen in 4th-8th decades of life with a peak in late 40s and early 50s. Benign Brenner tumors are usually small, <2cm in diameter and often detected incidentally during surgery or on pathological examination. Authors report a case of a large, calcified benign Brenner tumor in a 55-year-old postmenopausal woman who presented with complaint of abdominal pain and mass in abdomen. Imaging revealed large complex solid cystic pelvic mass -peritoneal fibrosarcoma. She underwent laparotomy which revealed huge Brenner tumor weighing 9kg arising from left uterine cornual end extending up to epigastric region. -

Rush University Medical Center, May 2005

TABLE OF CONTENTS Case # Title Page 1. Malignant Spitz’s Nevus 1 2. Giant Congenital Nevus 4 3. Methotrexate Nodulosis 7 4. Apthae with Trisomy 8–positive Myelodysplastic Syndrome 10 5. Kwashiorkor 13 6. “Unknown” 16 7. Gangrenous Cellulitis 17 8. Parry-Romberg Syndrome 21 9. Wegener’s Granulomatosis 24 10. Pediatric CTCL 27 11. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides 30 12. Fabry’s Disease 33 13. Cicatricial Alopecia, Unclassified 37 14. Mastocytoma 40 15. Cutaneous Piloleiomyomas 42 16. Granular Cell Tumor 44 17. Disseminated Blastomycoses 46 18. Neonatal Lupus 49 19. Multiple Lipomas 52 20. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali 54 21. Pigmented Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC) 57 Page 1 Case #1 CHICAGO DERMATOLOGICAL SOCIETY RUSH UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 18, 2005 CASE PRESENTED BY: Michael D. Tharp, M.D. Lady Dy, M.D., and Darrell W. Gonzales, M.D. History: This 2 year-old white female presented with a one year history of an expanding lesion on her left cheek. There was no history of preceding trauma. The review of systems was normal. Initially the lesion was thought to be a pyogenic granuloma and treated with two courses of pulse dye laser. After no response to treatment, a shave biopsy was performed. Because the histopathology was interpreted as an atypical melanocytic proliferation with Spitzoid features, a conservative, but complete excision with margins was performed. The pathology of this excision was interpreted as malignant melanoma measuring 4.0 mm in thickness. A sentinel lymph node biopsy was subsequently performed and demonstrated focal spindle cells within the subcapsular sinus of a left preauricular lymph node. -

Primary Desmoid Tumor of the Small Bowel: a Case Report and Literature Review

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.4915 Primary Desmoid Tumor of the Small Bowel: A Case Report and Literature Review Peter A. Ebeling 1 , Tristan Fun 1 , Katherine Beale 1 , Robert Cromer 2 , Jason W. Kempenich 1 1. Surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, USA 2. Surgery, Keesler U.S. Air Force Medical Center, Biloxi, USA Corresponding author: Peter A. Ebeling, [email protected] Abstract Desmoid tumors, also known as aggressive fibromatosis, are fibromuscular neoplasms that arise from mesenchymal cell lines. They may occur in almost all soft tissue compartments. Primary desmoids of the small bowel are rare but potentially serious tumors presenting unique challenges to the general surgeon. We present one case of a 59-year-old man presenting with three months of abdominal distension secondary to a small bowel desmoid. Computed tomography of the abdomen showed an 18-cm mass in the mid-abdomen without obvious vital structure encasement. Percutaneous biopsy of the mass indicated a desmoid tumor. The patient underwent a successful elective exploratory laparotomy with resection and primary enteric anastomosis. Final pathology revealed the mass to be a primary desmoid of the small bowel. His post- operative course was uneventful. At two years after surgery, he is symptom free, and there is no evidence of disease recurrence. Due to the rare nature of primary small bowel desmoids, there are few specific care pathways outlined. This is a challenging pathology to treat that often requires a multidisciplinary team of surgical and medical oncologists. Categories: General Surgery, Oncology Keywords: desmoid, small bowel, resection, aggressive fibromatosis Introduction Desmoid tumors, also known as aggressive fibromatosis, are fibromuscular neoplasms that arise from mesenchymal cell lines. -

Soft Tissue Cytopathology: a Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD

4/1/2020 Soft Tissue Cytopathology: A Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD Department of Pathology University of Pittsburgh Medical Center [email protected] What does the clinician want to know? • Is the lesion of mesenchymal origin or not? • Is it begin or malignant? • If it is malignant: – Is it a small round cell tumor & if so what type? – Is this soft tissue neoplasm of low or high‐grade? Practical diagnostic categories used in soft tissue cytopathology 1 4/1/2020 Practical approach to interpret FNA of soft tissue lesions involves: 1. Predominant cell type present 2. Background pattern recognition Cell Type Stroma • Lipomatous • Myxoid • Spindle cells • Other • Giant cells • Round cells • Epithelioid • Pleomorphic Lipomatous Spindle cell Small round cell Fibrolipoma Leiomyosarcoma Ewing sarcoma Myxoid Epithelioid Pleomorphic Myxoid sarcoma Clear cell sarcoma Pleomorphic sarcoma 2 4/1/2020 CASE #1 • 45yr Man • Thigh mass (fatty) • CNB with TP (DQ stain) DQ Mag 20x ALT –Floret cells 3 4/1/2020 Adipocytic Lesions • Lipoma ‐ most common soft tissue neoplasm • Liposarcoma ‐ most common adult soft tissue sarcoma • Benign features: – Large, univacuolated adipocytes of uniform size – Small, bland nuclei without atypia • Malignant features: – Lipoblasts, pleomorphic giant cells or round cells – Vascular myxoid stroma • Pitfalls: Lipophages & pseudo‐lipoblasts • Fat easily destroyed (oil globules) & lost with preparation Lipoma & Variants . Angiolipoma (prominent vessels) . Myolipoma (smooth muscle) . Angiomyolipoma (vessels + smooth muscle) . Myelolipoma (hematopoietic elements) . Chondroid lipoma (chondromyxoid matrix) . Spindle cell lipoma (CD34+ spindle cells) . Pleomorphic lipoma . Intramuscular lipoma Lipoma 4 4/1/2020 Angiolipoma Myelolipoma Lipoblasts • Typically multivacuolated • Can be monovacuolated • Hyperchromatic nuclei • Irregular (scalloped) nuclei • Nucleoli not typically seen 5 4/1/2020 WD liposarcoma Layfield et al. -

Immunohistochemical and Electron Microscopic Findings in Benign Fibroepithelial Vaginal Polyps J Clin Pathol: First Published As 10.1136/Jcp.43.3.224 on 1 March 1990

224 J Clin Pathol 1990;43:224-229 Immunohistochemical and electron microscopic findings in benign fibroepithelial vaginal polyps J Clin Pathol: first published as 10.1136/jcp.43.3.224 on 1 March 1990. Downloaded from T P Rollason, P Byrne, A Williams Abstract LIGHT MICROSCOPY Eleven classic benign "fibroepithelial Sections were cut from routinely processed, polyps" of the vagina were examined paraffin wax embedded blocks at 4 gm and using a panel of immunocytochemical immunocytochemical techniques were agents. Two were also examined electron performed using a standard peroxidase- microscopically. In all cases the stellate antiperoxidase method.7 The antibodies used and multinucleate stromal cells were as follows: polyclonal rabbit characteristic of these lesions stained antimyoglobin (batch A324, Dako Ltd, High strongly for desmin, indicating muscle Wycombe, Buckinghamshire), monoclonal intermediate filament production. In anti-desmin (batch M724, Dako Ltd), mono- common with uterine fibroleiomyomata, clonal anti-epithelial membrane antigen (batch numerous mast cells were also often M613, Dako Ltd), monoclonal anti-vimentin seen. Myoglobin staining was negative. (batch M725, Dako Ltd), polyclonal rabbit Electron microscopical examination anti-cytokeratin (Bio-nuclear services, Read- confirmed that the stromal cells con- ing) and monoclonal anti cytokeratin NCL tained abundant thin filaments with focal 5D3 (batch M503, Bio-nuclear services). densities and also showed the ultrastruc- Mast cells were shown by a standard tural features usually associated with chloroacetate esterase method using pararo- myofibroblasts. saniline,8 which gave an intense red cyto- It is concluded that these tumours plasmic colouration, and by the routine would be better designated polypoid toluidine blue method. myofibroblastomas in view of the above An attempt was made to assess semiquan- findings. -

Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of Blood Vessels 16 F.Ramon

16_DeSchepper_Tumors_and 15.09.2005 13:27 Uhr Seite 263 Chapter Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of Blood Vessels 16 F.Ramon Contents 42]. There are two major classification schemes for vas- cular tumors. That of Enzinger et al. [12] relies on 16.1 Introduction . 263 pathological criteria and includes clinical and radiolog- 16.2 Definition and Classification . 264 ical features when appropriate. On the other hand, the 16.2.1 Benign Vascular Tumors . 264 classification of Mulliken and Glowacki [42] is based on 16.2.1.1 Classification of Mulliken . 264 endothelial growth characteristics and distinguishes 16.2.1.2 Classification of Enzinger . 264 16.2.1.3 WHO Classification . 265 hemangiomas from vascular malformations. The latter 16.2.2 Vascular Tumors of Borderline classification shows good correlation with the clinical or Intermediate Malignancy . 265 picture and imaging findings. 16.2.3 Malignant Vascular Tumors . 265 Hemangiomas are characterized by a phase of prolif- 16.2.4 Glomus Tumor . 266 eration and a stationary period, followed by involution. 16.2.5 Hemangiopericytoma . 266 Vascular malformations are no real tumors and can be 16.3 Incidence and Clinical Behavior . 266 divided into low- or high-flow lesions [65]. 16.3.1 Benign Vascular Tumors . 266 Cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions are usually 16.3.2 Angiomatous Syndromes . 267 easily diagnosed and present no significant diagnostic 16.3.3 Hemangioendothelioma . 267 problems. On the other hand, hemangiomas or vascular 16.3.4 Angiosarcomas . 268 16.3.5 Glomus Tumor . 268 malformations that arise in deep soft tissue must be dif- 16.3.6 Hemangiopericytoma . -

Advances in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Bone Sarcoma Therapy T Pichaya Thanindratarna,B, Dylan C

Journal of Bone Oncology 15 (2019) 100221 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Bone Oncology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jbo Review Article Advances in immune checkpoint inhibitors for bone sarcoma therapy T Pichaya Thanindratarna,b, Dylan C. Deana, Scott D. Nelsonc, Francis J. Horniceka, ⁎ Zhenfeng Duana, a Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Sarcoma Biology Laboratory, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, 615 Charles E. Young. Dr. South, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA b Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Chulabhorn hospital, HRH Princess Chulabhorn College of Medical Science, Bangkok, Thailand c Department of Pathology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Bone sarcomas are a collection of sporadic malignancies of mesenchymal origin. The most common subtypes Immune checkpoint include osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and chordoma. Despite the use of aggressive treatment Immunotherapy protocols consisting of extensive surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, outcomes have not sig- Bone sarcoma nificantly improved over the past few decades for osteosarcoma or Ewing sarcoma patients. In addition, chon- Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drosarcoma and chordoma are resistant to both chemotherapy and radiation therapy. There is, therefore, an Anti-CTLA-4 urgent need to elucidate which novel new therapies may affect bone sarcomas. Emerging checkpoint inhibitors have generated considerable attention for their clinical success in a variety of human cancers, which has led to works assessing their potential in bone sarcoma management. Here, we review the recent advances of anti-PD-1/ PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 blockade as well as other promising new immune checkpoint targets for their use in bone sarcoma therapy. -

The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors In

Cancers 2020, 12 S1 of S7 Supplementary Materials The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors in Germany—Cross-Sectional Results of A Nationwide Observational Study (PROSa) Martin Eichler, Leopold Hentschel, Stephan Richter, Peter Hohenberger, Bernd Kasper, Dimosthenis Andreou, Daniel Pink, Jens Jakob, Susanne Singer, Robert Grützmann, Stephen Fung, Eva Wardelmann, Karin Arndt, Vitali Heidt, Christine Hofbauer, Marius Fried, Verena I. Gaidzik, Karl Verpoort, Marit Ahrens, Jürgen Weitz, Klaus-Dieter Schaser, Martin Bornhäuser, Jochen Schmitt, Markus K. Schuler and the PROSa study group Includes Entities We included sarcomas according to the following WHO classification. - Fletcher CDM, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. 468 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Kurman RJ, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, editors. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014. 307 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs—Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016 Jul;70(1):106–19. - World Health Organization, Swerdlow SH, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: [... reflects the views of a working group that convened for an Editorial and Consensus Conference at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, October 25 - 27, 2007]. 4. ed. -

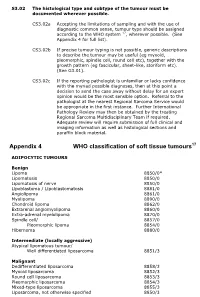

Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours17

S3.02 The histological type and subtype of the tumour must be documented wherever possible. CS3.02a Accepting the limitations of sampling and with the use of diagnostic common sense, tumour type should be assigned according to the WHO system 17, wherever possible. (See Appendix 4 for full list). CS3.02b If precise tumour typing is not possible, generic descriptions to describe the tumour may be useful (eg myxoid, pleomorphic, spindle cell, round cell etc), together with the growth pattern (eg fascicular, sheet-like, storiform etc). (See G3.01). CS3.02c If the reporting pathologist is unfamiliar or lacks confidence with the myriad possible diagnoses, then at this point a decision to send the case away without delay for an expert opinion would be the most sensible option. Referral to the pathologist at the nearest Regional Sarcoma Service would be appropriate in the first instance. Further International Pathology Review may then be obtained by the treating Regional Sarcoma Multidisciplinary Team if required. Adequate review will require submission of full clinical and imaging information as well as histological sections and paraffin block material. Appendix 4 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours17 ADIPOCYTIC TUMOURS Benign Lipoma 8850/0* Lipomatosis 8850/0 Lipomatosis of nerve 8850/0 Lipoblastoma / Lipoblastomatosis 8881/0 Angiolipoma 8861/0 Myolipoma 8890/0 Chondroid lipoma 8862/0 Extrarenal angiomyolipoma 8860/0 Extra-adrenal myelolipoma 8870/0 Spindle cell/ 8857/0 Pleomorphic lipoma 8854/0 Hibernoma 8880/0 Intermediate (locally