Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rare Bone Tumor

OPEN ACCESS L E T T E R T O T H E E D I T O R Periosteal Desmoplastic Fibroma of Radius: A Rare Bone Tumor Aniqua Saleem1,* Hira Saleem2 1 Radiology Department, District Head Quarters Hospital, Rawalpindi Medical University, Rawalpindi 2 Department of Surgery, Shifa International Hospital, Islamabad. Correspondence*: Dr. Aniqua Saleem, Radiology Department, District Head Quarters Hospital, Rawalpindi Medical University, Rawalpindi E-mail: [email protected] © 2019, Saleem et al, Submitted: 05-04-2019 Accepted: 09-06-2019 Conflict of Interest: None Source of Support: Nil This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. DEAR SIR Desmoplastic fibroma is an extremely rare tumor of enhancement on post contrast images and with adjacent bone with a reported incidence of 0.11 % of all primary bone involvement as was evident by focal cortical inter- bone tumors. The most common site of involvement is ruption, mild endosteal thickening and irregularity and mandible (reported incidence 22% of all Desmoplastic also mild ulnar shaft remodeling (Fig. 3a, 3b). To further fibroma cases) followed by metaphysis of long bones. characterize the lesion, Tc99 MDP (methylene diphos- Involvement of forearm especially involving periosteum phonate) bone scan was also performed which showed is seldom reported. Prompt diagnosis and adequate active bone involvement in left distal radial shaft. management is important for limb salvage and restora- tion of limb function. [1-3] An 11-year-old boy presented with painful mild swelling of left forearm for a month, with no significant past med- ical history or any history of trauma. -

Primary Mixed Myosarcoma of the Uterine Tube: a Case Report and Review of the Literature ALEXANDER S

Med. J. 258 CASE REPORT: MYOSAIRCOMAMYOSARCOMA OFUTERINEOF UTERINE TUBE Canad.Feb. 3, 1968, Ass.vol. 98 dans 1'cesophage superieur. Le plus petit malade REFERENCES chez qui une biopsie fut prelevee pesait 13 livres 1. CROSBY, W. H.: Amer. or. Dig. Dis., 8: 2, 1963. 2. CAREY, J. B., JR.: Gastroenterology, 46: 550, 1964. et 6tait age de 9 mois. 3. BECK, L T. et al.: Bull. Gastroint. EBndosc., 11: 15, 1965. We wish to thank 0. H. Kimbell, Ph.D., H. Robidoux- 4. MCDONALD, W. G.: Gastroenterology, 51: 390, 1966. 5. PARTIN, J. C. AND SCHUBERT, W. K: New Eng. J. Poirier, R.N., R.-M. Leblanc, R.N., D. Michaud, R.N., Med., 274: 94, 1966. and Marc Gigu6re, R.B.P., for their co-operation and 6. KUITUNEN, P. AND VISAKORPI, J. K.: Lancet, 1: 1276, active assistance. 1965. Primary Mixed Myosarcoma of the Uterine Tube: A Case Report and Review of the Literature ALEXANDER S. ULLMANN, M.D. and MAERIT B. KALLET, M.D., Detroit, Mich., U.S.A. SINCE primary malignant neoplasms of the uterine tube are so rare that no one indi- vidual or clinic has been able to study a large series of patients, the importance of reporting every case has often been emphasized.2-4 Although over 800 cases of primary carcinoma of the tube have been described in the liter- ature,4 up to 1956 only 30 authentic cases of primary sarcoma had been reported and to this number Abrams added another one.1' 8 Recently we had the opportunity to study a patient with primary sarcoma of the fallopian tube. -

A Case Report1 양측 흉막에 발생한 결합조직형성 소원형세포종양의 증례 보고1

Case Report pISSN 1738-2637 / eISSN 2288-2928 J Korean Soc Radiol 2015;72(4):295-299 http://dx.doi.org/10.3348/jksr.2015.72.4.295 Bilateral Presentation of Pleural Desmoplastic Small Round Cell Tumors: A Case Report1 양측 흉막에 발생한 결합조직형성 소원형세포종양의 증례 보고1 You Sun Won, MD1, Jai Soung Park, MD1, Sun Hye Jeong, MD1, Sang Hyun Paik, MD1, Heon Lee, MD1, Jang Gyu Cha, MD1, Eun Suk Koh, MD2 Departments of 1Radiology, 2Pathology, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Bucheon Hospital, Bucheon, Korea Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a highly aggressive malignant small cell neoplasm occurring mainly in the abdominal cavity, but it is extremely rare in Received October 13, 2014; Accepted December 21, the pleura. In this case, a 15-year-old male presented with a 1-month history of left 2014 chest pain. Chest radiographs revealed pleural thickening in the left hemithorax and Corresponding author: Jai Soung Park, MD Department of Radiology, Soonchunhyang University chest computed tomography showed multifocal pleural thickening with enhance- College of Medicine, Bucheon Hospital, 170 Jomaru-ro, ment in both hemithoraces. A needle biopsy of the left pleural lesion was performed Wonmi-gu, Bucheon 420-767, Korea. and the final diagnosis was DSRCT of the pleura. We report this unusual case aris- Tel. 82-32-621-5851 Fax. 82-32-621-5874 E-mail: [email protected] ing from the pleura bilaterally. The pleural involvement of this tumor supports the hypothesis that it typically occurs in mesothelial-lined surfaces. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) Index terms which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distri- Pleura bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the Thickened Pleura original work is properly cited. -

Primary Desmoid Tumor of the Small Bowel: a Case Report and Literature Review

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.4915 Primary Desmoid Tumor of the Small Bowel: A Case Report and Literature Review Peter A. Ebeling 1 , Tristan Fun 1 , Katherine Beale 1 , Robert Cromer 2 , Jason W. Kempenich 1 1. Surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, USA 2. Surgery, Keesler U.S. Air Force Medical Center, Biloxi, USA Corresponding author: Peter A. Ebeling, [email protected] Abstract Desmoid tumors, also known as aggressive fibromatosis, are fibromuscular neoplasms that arise from mesenchymal cell lines. They may occur in almost all soft tissue compartments. Primary desmoids of the small bowel are rare but potentially serious tumors presenting unique challenges to the general surgeon. We present one case of a 59-year-old man presenting with three months of abdominal distension secondary to a small bowel desmoid. Computed tomography of the abdomen showed an 18-cm mass in the mid-abdomen without obvious vital structure encasement. Percutaneous biopsy of the mass indicated a desmoid tumor. The patient underwent a successful elective exploratory laparotomy with resection and primary enteric anastomosis. Final pathology revealed the mass to be a primary desmoid of the small bowel. His post- operative course was uneventful. At two years after surgery, he is symptom free, and there is no evidence of disease recurrence. Due to the rare nature of primary small bowel desmoids, there are few specific care pathways outlined. This is a challenging pathology to treat that often requires a multidisciplinary team of surgical and medical oncologists. Categories: General Surgery, Oncology Keywords: desmoid, small bowel, resection, aggressive fibromatosis Introduction Desmoid tumors, also known as aggressive fibromatosis, are fibromuscular neoplasms that arise from mesenchymal cell lines. -

Soft Tissue Cytopathology: a Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD

4/1/2020 Soft Tissue Cytopathology: A Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD Department of Pathology University of Pittsburgh Medical Center [email protected] What does the clinician want to know? • Is the lesion of mesenchymal origin or not? • Is it begin or malignant? • If it is malignant: – Is it a small round cell tumor & if so what type? – Is this soft tissue neoplasm of low or high‐grade? Practical diagnostic categories used in soft tissue cytopathology 1 4/1/2020 Practical approach to interpret FNA of soft tissue lesions involves: 1. Predominant cell type present 2. Background pattern recognition Cell Type Stroma • Lipomatous • Myxoid • Spindle cells • Other • Giant cells • Round cells • Epithelioid • Pleomorphic Lipomatous Spindle cell Small round cell Fibrolipoma Leiomyosarcoma Ewing sarcoma Myxoid Epithelioid Pleomorphic Myxoid sarcoma Clear cell sarcoma Pleomorphic sarcoma 2 4/1/2020 CASE #1 • 45yr Man • Thigh mass (fatty) • CNB with TP (DQ stain) DQ Mag 20x ALT –Floret cells 3 4/1/2020 Adipocytic Lesions • Lipoma ‐ most common soft tissue neoplasm • Liposarcoma ‐ most common adult soft tissue sarcoma • Benign features: – Large, univacuolated adipocytes of uniform size – Small, bland nuclei without atypia • Malignant features: – Lipoblasts, pleomorphic giant cells or round cells – Vascular myxoid stroma • Pitfalls: Lipophages & pseudo‐lipoblasts • Fat easily destroyed (oil globules) & lost with preparation Lipoma & Variants . Angiolipoma (prominent vessels) . Myolipoma (smooth muscle) . Angiomyolipoma (vessels + smooth muscle) . Myelolipoma (hematopoietic elements) . Chondroid lipoma (chondromyxoid matrix) . Spindle cell lipoma (CD34+ spindle cells) . Pleomorphic lipoma . Intramuscular lipoma Lipoma 4 4/1/2020 Angiolipoma Myelolipoma Lipoblasts • Typically multivacuolated • Can be monovacuolated • Hyperchromatic nuclei • Irregular (scalloped) nuclei • Nucleoli not typically seen 5 4/1/2020 WD liposarcoma Layfield et al. -

The Use of High Tumescent Power Assisted Liposuction in the Treatment of Madelung’S Collar

Letter to the Editor The use of high tumescent power assisted liposuction in the treatment of Madelung’s collar Henryk Witmanowski1,2, Łukasz Banasiak1, Grzegorz Kierzynka1, Jarosław Markowicz1, Jerzy Kolasiński1, Katarzyna Błochowiak3, Paweł Szychta1,4 1Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Medical College in Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Poland 2Department of Physiology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland 3Department of the Oral Surgery, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland 4Department of Oncological Surgery and Breast Diseases, Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital-Research Institute, Lodz, Poland Adv Dermatol Allergol 2017; XXXIV (4): 366–371 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2017.69319 Mild symmetrical lipomatosis (plural symmetrical The disease most commonly takes a proximal form lipomatosis, multiple symmetric lipomatosis – MSL), which takes the following areas of the body with the fol- also known as Madelung’s disease or Launois-Bensaude lowing frequency: the genial area 92.3%, cervical region syndrome is a rare disease of unknown etiology, first de- 67.7%, shoulder region 54.8%, abdominal 45.2%, chest scribed by Brodie in 1846, Madelung in 1888, and Launois 41.9%, thigh and pelvic rim 32.3% [11, 12]. The periph- with Bensaude in 1898 [1–3]. eral type mainly locates on both sides at the level of the Madelung’s disease incidence is 1 : 250000 [4]. Mul- hands, feet and knees, this is definitely a rarer form of tiple symmetric lipomatosis occurs mainly in the inhabit- the disease. The mixed form is described very rarely. The ants of the Mediterranean area and Eastern Europe, in specified central type is also engaged primarily around males (male to female ratio is 20 : 1), aged 30–70 years, the lower torso, and intermediate parts of the legs. -

Uterine Carcinosarcoma Associated with Pelvic Radiotherapy for Sacral Chordoma: a Case Report

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 51 (2012) 89e92 www.tjog-online.com Case Report Uterine carcinosarcoma associated with pelvic radiotherapy for sacral chordoma: A case report Korhan Kahraman a,*, Fırat Ortac a, Duygu Kankaya b, Gulsah Aynaoglu a a Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey b Department of Pathology, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey Accepted 28 December 2010 Abstract Objective: Postirradiation sarcoma of the female genital tract is rare, but a recognized event. Most reported cases have been associated with history of radiotherapy for various gynecologic conditions, particularly cancer of the uterine cervix and abnormal uterine bleeding. The occurrence of uterine sarcoma secondary to radiotherapy for a non-gynecologic tumor and, furthermore, this condition being simultaneous with the recurrence of primary tumor is unique. Case Report: A 67-year-old woman presented with a uterine mass which was diagnosed as a sarcoma by endometrial curettage and history of pelvic radiotherapy 23 years previously for sacral chordoma. Surgical staging procedure for uterine malignancy was performed. The final pathologic diagnosis was carcinosarcoma of the uterus. Conclusion: In uterine masses seen in patients with history of irradiation to the pelvic field, the probability of uterine sarcomas should always be kept in mind. These tumors may occur simultaneously with recurrence of primary tumor previously treated by adjuvant radiation therapy. Copyright Ó 2012, Taiwan Association of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Published by Elsevier Taiwan LLC. -

The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors In

Cancers 2020, 12 S1 of S7 Supplementary Materials The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors in Germany—Cross-Sectional Results of A Nationwide Observational Study (PROSa) Martin Eichler, Leopold Hentschel, Stephan Richter, Peter Hohenberger, Bernd Kasper, Dimosthenis Andreou, Daniel Pink, Jens Jakob, Susanne Singer, Robert Grützmann, Stephen Fung, Eva Wardelmann, Karin Arndt, Vitali Heidt, Christine Hofbauer, Marius Fried, Verena I. Gaidzik, Karl Verpoort, Marit Ahrens, Jürgen Weitz, Klaus-Dieter Schaser, Martin Bornhäuser, Jochen Schmitt, Markus K. Schuler and the PROSa study group Includes Entities We included sarcomas according to the following WHO classification. - Fletcher CDM, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. 468 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Kurman RJ, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, editors. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014. 307 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs—Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016 Jul;70(1):106–19. - World Health Organization, Swerdlow SH, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: [... reflects the views of a working group that convened for an Editorial and Consensus Conference at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, October 25 - 27, 2007]. 4. ed. -

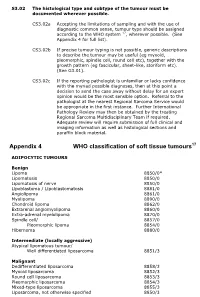

Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours17

S3.02 The histological type and subtype of the tumour must be documented wherever possible. CS3.02a Accepting the limitations of sampling and with the use of diagnostic common sense, tumour type should be assigned according to the WHO system 17, wherever possible. (See Appendix 4 for full list). CS3.02b If precise tumour typing is not possible, generic descriptions to describe the tumour may be useful (eg myxoid, pleomorphic, spindle cell, round cell etc), together with the growth pattern (eg fascicular, sheet-like, storiform etc). (See G3.01). CS3.02c If the reporting pathologist is unfamiliar or lacks confidence with the myriad possible diagnoses, then at this point a decision to send the case away without delay for an expert opinion would be the most sensible option. Referral to the pathologist at the nearest Regional Sarcoma Service would be appropriate in the first instance. Further International Pathology Review may then be obtained by the treating Regional Sarcoma Multidisciplinary Team if required. Adequate review will require submission of full clinical and imaging information as well as histological sections and paraffin block material. Appendix 4 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours17 ADIPOCYTIC TUMOURS Benign Lipoma 8850/0* Lipomatosis 8850/0 Lipomatosis of nerve 8850/0 Lipoblastoma / Lipoblastomatosis 8881/0 Angiolipoma 8861/0 Myolipoma 8890/0 Chondroid lipoma 8862/0 Extrarenal angiomyolipoma 8860/0 Extra-adrenal myelolipoma 8870/0 Spindle cell/ 8857/0 Pleomorphic lipoma 8854/0 Hibernoma 8880/0 Intermediate (locally -

Discover Seventh Chords

Seventh Chords Stack of Thirds - Begin with a major or natural minor scale (use raised leading tone for chords based on ^5 and ^7) - Build a four note stack of thirds on each note within the given key - Identify the characteristic intervals of each of the seventh chords w w w w w w w w % w w w w w w w Mw/M7 mw/m7 m/m7 M/M7 M/m7 m/m7 d/m7 w w w w w w % w w w w #w w #w mw/m7 d/wm7 Mw/M7 m/m7 M/m7 M/M7 d/d7 Seventh Chord Quality - Five common seventh chord types in diatonic music: * Major: Major Triad - Major 7th (M3 - m3 - M3) * Dominant: Major Triad - minor 7th (M3 - m3 - m3) * Minor: minor triad - minor 7th (m3 - M3 - m3) * Half-Diminished: diminished triad - minor 3rd (m3 - m3 - M3) * Diminished: diminished triad - diminished 7th (m3 - m3 - m3) - In the Major Scale (all major scales!) * Major 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 2, 3, 6 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 - In the Minor Scale (all minor scales!) with a raised leading tone for chords on ^5 and ^7 * Major 7th on scale degrees 3 & 6 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 2 * Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 Using Roman Numerals for Triads - Roman Numeral labels allow us to identify any seventh chord within a given key. -

Lumps and Bumps of the Abdominal Wall and Lumbar Region—Part 2: Beyond Hernias

Published online: 2019-06-18 THIEME Review Article 19 Lumps and Bumps of the Abdominal Wall and Lumbar Region—Part 2: Beyond Hernias Sangoh Lee1 Catalin V. Ivan1 Sarah R. Hudson1 Tahir Hussain1 Suchi Gaba2 Ratan Verma1 1 1 Arumugam Rajesh James A. Stephenson 1Department of Radiology, University Hospitals of Leicester, Address for correspondence James A. Stephenson, MD, FRCR, Leicester General Hospital, Leicester, United Kingdom Department of Radiology, University Hospitals of Leicester, 2Department of Radiology, University Hospitals of North Midlands, Leicester General Hospital, Leicester, LE5 4PW, United Kingdom Royal Stoke University Hospital, Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom (e-mail: [email protected]). J Gastrointestinal Abdominal Radiol ISGAR 2018;1:19–32 Abstract Abdominal masses can often clinically mimic hernias, especially when they are locat- ed close to hernial orifices. Imaging findings can be challenging and nonspecific Keywords with numerous differential diagnoses. We present a variety of pathology involving ► abdominal wall the abdominal wall and lumbar region, which were referred as possible hernias. This ► hernia demonstrates the wide-ranging pathology that can present as abdominal wall lesions ► mimics or mimics of hernias that the radiologist should be alert to. Introduction well-differentiated liposarcomas are histologically identical. The term “atypical lipoma” was coined by Evans et al in 1979 to An abdominal hernia occurs when an organ of a body ca vity describe well-differentiated liposarcoma of subcutaneous and 1 protrudes through a defect in the wall of that cavity. It is a 6 intramuscular layers. The World Health Organization (WHO) common condition with lifetime risk of developing a groin has further refined the definition by using atypical lipoma to hernia being estimated at 27% for men and 3% for women; it has describe subcutaneous lesions only and well- differentiated 2 thus been covered extensively in the literature. -

Acral Manifestations of Soft Tissue Tumors Kristen M

Clinics in Dermatology (2017) 35,85–98 Acral manifestations of soft tissue tumors Kristen M. Paral, MD, Vesna Petronic-Rosic, MD, MSc⁎ Section of Dermatology, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Chicago, IL Abstract This group of biologically diverse entities is united by topographic localization to the hands and feet. Categorizing tumors by body site narrows the differential into a short list of possibilities that can facil- itate accurate and rapid diagnosis. The goal of this review is to provide a practical approach to soft tissue tumors of acral locations for clinicians, pathologists, and researchers alike. What ensues in the following text is that tight coupling of the clinical picture and histopathologic findings should produce the correct diagno- sis, or at least an abbreviated differential. The salient clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molec- ular features are presented alongside current treatment recommendations for each entity. © 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction actin (SMA) and are deemed “myofibroblasts.”1 The tumors under this heading express combinations of CD34, FXIIIa, fi The entities presented herein are categorized on the basis of and SMA. The synthesis of collagen by broblasts translates fi fi morphogenesis (where possible) and by biologic potential as to a brous consistency that clinically imparts a rm texture benign, intermediate, and malignant neoplasms. on palpation, and, macroscopically, a gray-white or white-tan cut surface. The entities discussed next have no metastatic po- tential; that is, simple excision is adequate. Fibrous and related tissues: Benign lesions Fibroma of tendon sheath fi fl The ontogenetic classi cation of benign lesions re ects appar- Also known as tenosynovial fibroma, compared with other fi fi fi ent broblastic or broblast-like morphogenesis.