Radio and Development in Africa a Concept Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year in Review 2008

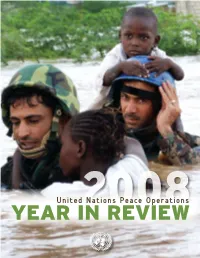

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

WT Cox Information Services 300 Popular Titles Public Libraries

WT Cox Information Services 300 Popular Titles Public Libraries For personalized pricing contact WT Cox Information Services. 110% Gaming Astronomy Magazine AARP Membership Atlantic, The (American Association of Retired Persons) Action Comics AV Technology Allrecipes Magazine Allure ADDING VALUE TO SOFT-CODEC SOLUTIONS Leading resource in the VOL.12 NO.1 | THE AV RESOURCE FOR TECHNOLOGY MANAGERS AND USERS Amazing Spiderman BIG LITTLE MEETINGS audio visual and IT MAKING HUDDLE-SIZED JANUARY 2019 American Craft Council | SPACES WORK technology industry for American History AVNETWORK.COM decision makers charged American Journal of Nursing (AJN) with procuring and TOP-NOTCH American Patchwork & Quilting TEAMWORK maintaining AV and IT THE TECHNOLOGY MANAGER’S GUIDE TO COLLABORATION SOLUTIONS SPECIAL FEATURE American Teen Companies to systems. It provides the +Watch in 2019 Animal Tales tools and tips they need Animation Magazine to stay informed. With the Aperture latest news, techniques, Archaeology reviews, and insights Architectural Digest from today’s top AV Art in America managers. ARTFORUM International Artist's Magazine, The ArtNews Avengers Aviation Week & Space Technology Ask Magazine (Arts & Sciences for Kids) Awesome Science Each themed issue of ASK invites newly independent While Awesome may be a readers to explore the mythical dragon, the topics we world of science and ideas cover are anything but! with topics that really Adventure through chapters of appeal to kids, from pirates oceanography, biology, anatomy, to plasma. Filled with lively, environmental science, well-written articles, vivid chemistry, physics, forensic graphics, activities, science, mathematics and cartoons, and plenty of technology! We offer humor, ASK is science that comprehensive teacher reviews kids demand to read! and challenges for readers to Grades 3-5. -

The Regulation of Commercial Radio Broadcasting in the United Kingdom

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 14 Number 2 Article 5 Spring 1989 The Regulation of Commercial Radio Broadcasting in the United Kingdom Timothy H. Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Part of the Commercial Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Timothy H. Jones, The Regulation of Commercial Radio Broadcasting in the United Kingdom, 14 N.C. J. INT'L L. 255 (1989). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol14/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Regulation of Commercial Radio Broadcasting in the United Kingdom Timothy H. Jones* The regulation of commercial radio broadcasting in the United Kingdom is about to enter a period of rapid change. The Govern- ment is committed to increasing the number of commercial radio sta- tions and to a measure of deregulation. Legislation to effect these changes is expected in the near future. Up to the present time, an independent agency, the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA or Authority), has strictly regulated commercial radio broadcasting.' Commercial radio services have been restricted to those of a "local" character.2 This regulation of Independent Local Radio (ILR) is generally regarded to have been a failure, and the IBA's effectiveness as a regulatory agency has been called into question on numerous occasions. -

Warburton, John Henry. (2010). Picture Radio

! ∀# ∃ !∃%& ∋ ! (()(∗( Picture Radio: Will pictures, with the change to digital, transform radio? John Henry Warburton Master of Philosophy Southampton Solent University Faculty of Media, Arts and Society July 2010 Tutor Mike Richards 3 of 3 Picture Radio: Will pictures, with the change to digital, transform radio? By John Henry Warburton Abstract This work looking at radio over the last 80 years and digital radio today will consider picture radio, one way that the recently introduced DAB1 terrestrial digital radio could be used. Chapter one considers the radio history including early picture radio and television, plus shows how radio has come from the crystal set, with one pair of headphones, to the mains powered wireless with built in speakers. These radios became the main family entertainment in the home until television takes over that role in the mid 1950s. Then radio changed to a portable medium with the coming of transistor radios, to become the personal entertainment medium it is today. Chapter two and three considers the new terrestrial digital mediums of DAB and DRM2 plus how it works, what it is capable of plus a look at some of the other digital radio platforms. Chapter four examines how sound is perceived by the listener and that radio broadcasters will need to understand the relationship between sound and vision. We receive sound and then make pictures in the mind but to make sense of sound we need codes to know what it is and make sense of it. Chapter five will critically examine the issues of commercial success in radio and where pictures could help improve the radio experience as there are some things that radio is restricted to as a sound only medium. -

Growing Community Conservation Agriculture Over the Airwaves

Winter 2019 farmradio.org Legacy Giving Farm Radio International enables you to leave a lasting legacy — your commitment to changing the lives of farming families and their communities across Africa. A bequest of any size can have a significant impact on long-term sustainability of our work. For more information, contact Brenda Jackson at 1-888-773-7717 x3646 or [email protected]. GROWING COMMUNITY CONSERVATION AGRICULTURE OVER THE AIRWAVES © John Klassen Matefie Meja is a single mother of For Matefie, conservation conservation agriculture practices, three who farms a half-hectare of agriculture means no plowing. giving farmers the information they land in Chifisa, Ethiopia. Matefie learned to intercrop need to test the practices in their It’s intensive work as she has no pumpkins and maize, and spread own fields. ox to plow the land. Weeding is a crops on her field to keep moisture Matefie listened to the radio time consuming chore for her, one from evaporating. The process gave programs with a group of women in that leaves her little time to complete Matefie more time for her other her community. the other work she must do to keep chores, while she watched her crops “Because of the listening group, her farm running smoothly. grow tall and productive. the single women farmers in our Recently, thanks to a radio The radio program that Matefie village felt, for the first time, equal to program that explained conservation learned from was part of a men farmers,” she says. agriculture to her — a farming collaborative project launched by “We were involved in the discussion approach that emphasizes protecting the Canadian Foodgrains Bank in about improving our farms and we the soil and the environment in Ethiopia on conservation agriculture, felt listened to. -

History of Radio Broadcasting in Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1963 History of radio broadcasting in Montana Ron P. Richards The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Richards, Ron P., "History of radio broadcasting in Montana" (1963). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5869. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5869 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF RADIO BROADCASTING IN MONTANA ty RON P. RICHARDS B. A. in Journalism Montana State University, 1959 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1963 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number; EP36670 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oiuartation PVUithing UMI EP36670 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

DR-CONGO December 2013

COUNTRY REPORT: DR-CONGO December 2013 Introduction: other provinces are also grappling with consistently high levels of violence. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DR-Congo) is the sec- ond most violent country in the ACLED dataset when Likewise, in terms of conflict actors, recent international measured by the number of conflict events; and the third commentary has focussed very heavily on the M23 rebel most fatal over the course of the dataset’s coverage (1997 group and their interactions with Congolese military - September 2013). forces and UN peacekeepers. However, while ACLED data illustrates that M23 has constituted the most violent non- Since 2011, violence levels have increased significantly in state actor in the country since its emergence in April this beleaguered country, primarily due to a sharp rise in 2012, other groups including Mayi Mayi militias, FDLR conflict in the Kivu regions (see Figure 1). Conflict levels rebels and unidentified armed groups also represent sig- during 2013 to date have reduced, following an unprece- nificant threats to security and stability. dented peak of activity in late 2012 but this year’s event levels remain significantly above average for the DR- In order to explore key dynamics of violence across time Congo. and space in the DR-Congo, this report examines in turn M23 in North and South Kivu, the Lord’s Resistance Army Across the coverage period, this violence has displayed a (LRA) in northern DR-Congo and the evolving dynamics of very distinct spatial pattern; over half of all conflict events Mayi Mayi violence across the country. The report then occurred in the eastern Kivu provinces, while a further examines MONUSCO’s efforts to maintain a fragile peace quarter took place in Orientale and less than 10% in Ka- in the country, and highlights the dynamics of the on- tanga (see Figure 2). -

Dismissed! Victims of 2015-2018 Brutal Crackdowns in the Democratic Republic of Congo Denied Justice

DISMISSED! VICTIMS OF 2015-2018 BRUTAL CRACKDOWNS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DENIED JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: “Dismissed!”. A drawing by Congolese artist © Justin Kasereka (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 62/2185/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND: POLITICAL CRISIS 10 3.1 ATTEMPTS TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION 10 3.2 THE « GLISSEMENT »: THE LONG-DRAWN-OUT ELECTORAL PROCESS 11 3.3 ELECTIONS AT LAST 14 3.3.1 TIMELINE 15 4. VOICES OF DISSENT MUZZLED 19 4.1 ARBITRARY ARRESTS, DETENTIONS AND SYSTEMATIC BANS ON ASSEMBLIES 19 4.1.1 HARASSMENT AND ARBITRARY ARRESTS OF PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS AND OPPONENTS 20 4.1.2 SYSTEMATIC AND UNLAWFUL BANS ON ASSEMBLY 21 4.2 RESTRICTIONS OF THE RIGHT TO SEEK AND RECEIVE INFORMATION 23 5. -

Mapping Conflict Motives: M23

Mapping Conflict Motives: M23 1 Front Cover image: M23 combatants marching into Goma wearing RDF uniforms Antwerp, November 2012 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 1. Background 5 2. The rebels with grievances hypothesis: unconvincing 9 3. The ethnic agenda: division within ranks 11 4. Control over minerals: Not a priority 14 5. Power motives: geopolitics and Rwandan involvement 16 Conclusion 18 3 Introduction Since 2004, IPIS has published various reports on the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Between 2007 and 2010 IPIS focussed predominantly on the motives of the most significant remaining armed groups in the DRC in the aftermath of the Congo wars of 1996 and 1998.1 Since 2010 many of these groups have demobilised and several have integrated into the Congolese army (FARDC) and the security situation in the DRC has been slowly stabilising. However, following the November 2011 elections, a chain of events led to the creation of a ‘new’ armed group that called itself “M23”. At first, after being cornered by the FARDC near the Rwandan border, it seemed that the movement would be short-lived. However, over the following two months M23 made a remarkable recovery, took Rutshuru and Goma, and started to show national ambitions. In light of these developments and the renewed risk of large-scale armed conflict in the DRC, the European Network for Central Africa (EURAC) assessed that an accurate understanding of M23’s motives among stakeholders will be crucial for dealing with the current escalation. IPIS volunteered to provide such analysis as a brief update to its ‘mapping conflict motives’ report series. -

Review of BBC Local Radio Report Prepared for BBC Management

Review of BBC Local Radio Report prepared for BBC Management John Myers February, 2012 Myers review of BBC Local Radio - January 2012 Preface In November 2011, I was asked by BBC management to review the operations of BBC Local Radio. The brief was to examine the working practices of the local radio network, to investigate areas of possible savings without impacting the on-air performance and review the current levels of management and back office staff. This work was conducted over a short period of time and therefore my findings can only be considered to be an overview. Furthermore, this is my personal opinion based on what I have learned and is certainly not meant to be a detailed cost analysis of each station or the network as a whole which would require extensive and detailed work to be carried out over a longer period of time. In addition, the savings are approximate totals and are not meant to be precise. While my task was not to review content specifically, I did so if I felt it impacted on the cost of running local radio or where it provides context, colour or background to a particular point. Where practical, I have offered a solution to any issues uncovered if it is not contained within my main findings and recommendations. The review was carried out between the 11th November and the 9th December respectively and nine stations were visited within the network portfolio. These were Cumbria, Essex, Merseyside, Shropshire, Nottingham, Tees, Manchester, Oxford and BBC Sussex and Surrey. I was assisted in this task by the BBC‟s Policy and Strategy team. -

Annual Report

2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT About 2019 - 2020 Farm Radio International Year in Review We are pleased to present to you our annual had been making into reverse, affecting gains who we ARE Our work in report for the 2019-20 fiscal year. in health and nutrition, agricultural and poverty It was an important year for Farm Radio reduction. It was not the first disaster of the year We are an international non-governmental 2019 - 2020 International. First, we celebrated the as farmers also faced locust infestations, floods, organization uniquely focused on improving the organization’s 40th birthday! Four decades have and other fresh challenges to food security in lives of rural Africans through the world’s most passed since George Atkins, together with many parts of Africa. accessible communication tool: RADIO. many partners, volunteers and backers, put During the pandemic, we became very aware 13 together the first package of Farm Radio scripts of how critically important radio is in times of million listeners and distributed it to 34 radio broadcasters in emergency and as people cope with and adapt to OUR MISSION underserved communities. Much has changed major change. While COVID-19 quickly made the since then, but the essence remains much the logistics of our work more challenging, the need We make radio a powerful force for good in rural same — a conviction that ordinary farming for — and the urgency of — credible, reliable, and Africa — one that shares knowledge, amplifies 2.7 families, no matter where they live, need and trustworthy radio programs and services became voices, and supports positive change. -

Kothmale Community Radio Interorg Project: True Community Radio Or Feel-Good Propaganda?

International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning Volume 10, Number 1. ISSN: 1492-3831 February – 2009 Kothmale Community Radio Interorg Project: True Community Radio or Feel-Good Propaganda? Liz Harvey-Carter M.A. Integrated Studies Athabasca University Abstract The Kothmale Community Radio and Interorg project in Sri Lanka has been hailed as an example of how a community radio initiative should function in a developing nation. However, there is some question about whether the Kothmale Community Interorg Project is a true community radio initiative that empowers local communities to access ICT services and to participate freely and equally or another ―feel- good‖ project controlled by successive, repressive Sri-Lankan governments and international partners, as alleged by its critics? After two decades of operation, the evidence shows that the Kothmale project is a cautionary tale about what can go wrong when an ICT project is not strongly promoted as a community- based enterprise. The biggest lesson that the Kothmale model can teach us is that control of community radio must be in the hands of the community exclusively if it is to succeed. Keywords: Kothmale, Community Radio, Sri Lanka, ICT, Kothmale Interorg Project Introduction The Kothmale Community Radio Project in Sri Lanka, now called the Kothmale Community Interorg Project, has been hailed as an example of how a community radio initiative should function within a developing nation, particularly one that has been embroiled in a long, brutal civil war (FAO, no date; Hughes, 2003; IDS, 2002; Jayaweera, 1998; Op de Coul, 2003; Seneviratne, 2007; Seneviratne, 2000). While this project is described as a success, ostensibly enabling the limited community it serves to participate in ICT and to decide which aspects of their culture(s) will be broadcast or featured on air or online, it can be argued that it has failed to realize its promise as an engine for change and freedom of expression (Gunawardene, 2007).