Sustainable Development Through Tourism: Conflicts Between Theory and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

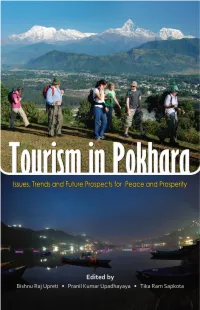

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity 1 Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity Edited by Bishnu Raj Upreti Pranil Kumar Upadhayaya Tikaram Sapkota Published by Pokhara Tourism Council, Pokhara South Asia Regional Coordination Office of NCCR North-South and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research, Kathmandu Kathmandu 2013 Citation: Upreti BR, Upadhayaya PK, Sapkota T, editors. 2013. Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity. Kathmandu: Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), South Asia Regional Coordination Office of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North- South) and Nepal Center for Contemporary Research (NCCR), Kathmandu. Copyright © 2013 PTC, NCCR North-South and NCCR, Kathmandu, Nepal All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-9937-2-6169-2 Subsidised price: NPR 390/- Cover concept: Pranil Upadhayaya Layout design: Jyoti Khatiwada Printed at: Heidel Press Pvt. Ltd., Dillibazar, Kathmandu Cover photo design: Tourists at the outskirts of Pokhara with Mt. Annapurna and Machhapuchhre on back (top) and Fewa Lake (down) by Ashess Shakya Disclaimer: The content and materials presented in this book are of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North-South) and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research (NCCR). Dedication To the people who contributed to developing Pokhara as a tourism city and paradise The editors of the book Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity acknowledge supports of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC) and the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South, co-funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the participating institutions. -

Overview Itinerary Details

Annapurna Circuit Trekking Overview There are very less trekking itineraries in Nepal which command as much attention of the visiting tourists as does the Annapurna Circuit Trekking. The popular trekking route of Annapurna Circuit lies in the Western part of the country, nearby from the popular tourist town of Pokhara. No wonder, Annapurna Sanctuary Trekking is a wonderful opportunity for the visiting tourists to learn and explore more about the fascinating region of Annapurna which is popular both inside and outside the country. It is by far the most amazing and popular trekking destination in the Annapurna region of Nepal. Annapurna region is crowded throughout the year as the visiting tourists come here to enjoy the adventures of Nepal trek and also to enjoy the natural sightseeing in the famous region. Annapurna Circuit Trekking with the ‘Nepal Glacier Treks’ is a 21-day trekking itinerary during the course of which the visiting tourists can witness the beauty of the Annapurna region, enjoy trekking in Nepal, and also observe the greatness of the popular Thorong-La Pass while also get the chance to visit the holy shrine of Muktinath. The shrine of Muktinath is a major highlight of the circuit trekking as many domestic tourists come here for pilgrimage purpose as well. The Hindu temple of Muktinath is located at around 3700 meters of altitude. The valley of Manang and the places like Jomsom are other major attractions of the Annapurna Circuit Trekking. The maximum elevation which the trekkers reach during Circuit trekking will be around 5400 meters, while the months of September- November and March-May are best for the trekking. -

SASEC) Power System Expansion Project (SPEP

Environmental Impact Assessment February 2014 NEP: South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC) Power System Expansion Project (SPEP) Prepared by Nepal Electricity Authority for the Asian Development Bank. This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Asian Development Bank Nepal: South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC) Power System Expansion Project (SPEP) On-grid Components ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Draft – February 2014 i ADB TA 8272-NEP working draft – February 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Policy, Legal, and Administrative Framework 4 3 Description of the Project 19 4 Description of the Environment 28 Anticipated Environmental Impacts and Mitigation 5 96 Measures Information Disclosure, Consultation, and 6 112 Participation 7 Environmental Management Program 115 8 Conclusions and Recommendations 12 8 Appendices 1 Important Flora and Fauna 13 7 2 Habitat Maps 15 9 3 Summary of Offsetting Activities 16 9 Routing Maps in Annapurna Conservation Area -

Life Members of Pun Samaaj UK

Life Members of Pun Samaaj UK M/No Full Name Thar Add in UK Add in Nepal Remarks 001 Maj Santa Purja Pun MBE Swindon Shikha 002 Mr Sher Bdr Armaja Pun Northolt Lopre 003 Mr Ati Parsad Pahere Pun South Harrow Kuwapani 004 Mr Tilak Pahere Pun Swindon Histan 005 Mr Birkharam Purja Pun Basingstoke Shikha 006 Mr Janga Bdr Buduja Pun Basingstoke Ghorepani 007 Mr Kamal Purja Pun Winchester Dana 008 Mr Ram Bdr Tilija Pun Bracknell Banduk 009 Maj Ratna Purja Pun Brunei Khibang 010 Maj Bishnu Garbuja Pun Salisbury Ramche 011 Mr Dil Bahadur Pahare Pun Basingstoke Shikha 012 Mr Cham Bdr Garbuja Pun Hounslow Kaphaldanda 013 Capt. Chandra Pahere Pun Reading Histan 014 Lt. Padam Bdr Purja Pun Basingstoke Begkhola 015 Lt. Raju Sherpuja Pun Northolt Paudwar 016 Mr Kamansing Purja Pun Northolt Okhareni 017 Mr Deuman Garbuja Pun Feltham Doba 018 Mr Khum Bdr Garbuja Pun Ruislip Khibang 019 Mr Bal Bahadur Pahere Pun Sudbury Histan 020 Mr Deujit Tilija Pun Swindon Ramche 021 Mr Chalak Buduja Pun Camberley Ghorepani 022 Mr Man Bahadur Paija Pun Plumpstead Shikha 023 Mr Om Parsad Purja Pun Colchester Banduk 024 Mr Chandra Bdr Pahere Pun Reading Shikha 025 Mr Jas Bahadur Paija Pun Aldershot Paudwar 026 Mr Nardev Tilija Pun Ashford Shikha 027 Mr Hom Bdr Phagami Pun Basingstoke Gharamdi 028 Mr Maniram Phagami Pun Basingstoke Shikha 029 Mr Hemchandra Paija Pun Basingstoke Thotneri 030 Mr Dhanbir Buduja Pun Basingstoke Ghorepani 031 Mr Tek Bahadur Garbuja Pun Basingstoke Shikha 032 Mr Khakka Bdr Purja Pun Basingstoke Shikha 033 Mr Rajendra Paija Pun Basingstoke Shikha 034 Mr Om Bahadur Khorja Pun Basingstoke Ulleri 035 Mr Sunil Khorja Pun Basingstoke Ulleri 036 Mr Yogendra Purja Pun Basingstoke Begkhola 037 Mr Gyan Bdr Paija Pun Basingstoke Shikha 038 Mr Hom Bdr Garbuja Pun Feltham Dandakateri 039 Capt. -

Climate Change, "Everestification,"

CLIMATE CHANGE, "EVERESTIFICATION," AND THE FUTURE OF MOUNTAINEERING ON ANNAPURNA I by Jamie Leanne Hutchinson A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Environmental Studies The Evergreen State College June 2020 ©2020 by Jamie Hutchinson. All rights reserved. This Thesis for the Master of Environmental Studies Degree by Jamie Hutchinson has been approved for The Evergreen State College by ________________________ Kathleen Saul, Ph. D. Member of the Faculty ________________________ Date ABSTRACT Climate Change, "Everestification", and the Future of Mountaineering on Annapurna I Jamie Hutchinson This study aims to research how climate change is affecting the Annapurna Conservation Area in the Western Region of Nepal. This region consists of two mountain districts, three hill districts, and encompasses the Annapurna massif. Temperature and Precipitation data was obtained from the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology, Nepal, spanning thirty years (1988-2018). Monthly, Seasonal and Yearly data were aggregated and averaged for both datasets, and statistical analysis was completed using JMP and Excel. Results indicate overall warming in all districts by 1°C, with higher elevations being impacted more than lower. Precipitation tests show strong seasonal intensity in the summer months, sometimes predating monsoon season, with higher elevations receiving less snow than previously recorded. Additional focus was then turned to Annapurna I in order to analyze expedition data for the last thirty years (1989 – 2019). All 8,000-meter peaks within Nepal were studied for expedition size and experience in order to establish climbing trends that lead to "Everestification." Current trends show an increase in expedition size but a overall decrease in inexperienced climbers. -

Andrées De Ruiter and Prem Rai Trekking the Annapurna Circuit Including New NATT-Trails Which Avoid the Road

Andrées de Ruiter and Prem Rai Trekking the Annapurna Circuit including new NATT-trails which avoid the road Andrées de Ruiter and Prem Rai Trekking the Annapurna Circuit including new NATT-trails which avoid the road A guide book to one of the finest trekking areas of Nepal and the world NATT = New Annapurna Trekking Trail This Edition 2011 was written based on information gathered during August and September 2011 Free version on the internet. This text will also soon be published as a paperback much more convenient to carry with you at Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt ISBN: 9783844800364 The authors Andrées de Ruiter Born 1956 in Belgium he lives now in Germany. He travelled the first time to Nepal in 1981 on a nine month overland journey to Asia. His first trek was to Manang. Since then he has come to Nepal some 30 more times. His favourite area is the Annapurna region which he visited several times. Andrées de Ruiter works as a freelance consultant for quality management. He has a large website with information about different trekking areas and especially of the Annapurna area: www.nepal-dia.de , email: [email protected] . Prem Rai Was born in1975 at the little hamlet called Sintup of Sankhuwashaba district in the north part of east Nepal, he grew up in a farmer family. He moved with his Wife Maina and son Shyam to north of Pokhara in 1997 and to Pokhara in 1999 when he started working as Porterguide. In 2004 he had received the Governmental license as a trekking guide. -

Nepal Wireless Networking Project Nepal Wireless Networking Project

Nepal Wireless Networking Project Case Study and Evaluation Report Prepared by: Mahabir Pun Robin Shields Rajendra Poudel Philip Mucci http://www.nepalwireless.net September, 2006 1 Preface ........................................................................................................................................3 1. Introduction.............................................................................................................................4 1.1 Goals and Objectives........................................................................................................ 5 2. Project Implementation...........................................................................................................7 2.1 Network Service Area .................................................................................................... ..8 2.2 Access Technology Used ............................................................................................... 11 2.3 Transport Technology Used........................................................................................... 13 2.3.1 Wireless Devices Used ........................................................................................... 13 2.3.2 Network Server Set up ............................................................................................ 14 2.3.2 Power Generation at the Relay Stations.................................................................. 18 2.4 Financial Data of the Project......................................................................................... -

Nepal Luxury Trekking Itineraries

Nepal in Comfort Luxury trekking itineraries in Nepal Table of Contents Sacred Mountain Trek ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Annapurna Base Camp Trek ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Annapurna Everest Spectacular ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Royal Nepal Spectacular ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 10 Nepal Panorama ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 13 Optional Extensions .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Price Guide ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Initial Environmental Examination NEPAL: Electricity Grid

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Final Project Number: 54107-001 August 2020 NEPAL: Electricity Grid Modernization Project Part 1 Prepared by Nepal Electricity Authority, Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 12 August 2020) Currency Unit = Nepali Rupee/s (Rs) Rs1.00 = $0.008344 $1.00 = Rs119.8400 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AIS air insulated substation CBS Central Bureau of Statistics CE common era CO2 carbon dioxide COD chemical oxygen demand DHM Department of Hydrology and Meteorology DO dissolved oxygen EGMP electricity grid modernization project EHS environment, health, and safety EIA environmental impact assessment EMF electromagnetic field EMP environmental management plan EPI environmental performance index GIS gas insulated substation GRM grievance redress mechanism HDI human development index IEE initial environmental examination IEEE Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineer Inc. ICNRP International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature kV kilovolt LPG liquefied petroleum gas masl meters above sea level mm millimeter µg/m³ micro gram per cubic meter NEA Nepal Electricity Authority PM2.5 fine particulate matter below 2.5 micrometers PMD project management directorate PTDEEP Power Transmission and Distribution Efficiency Enhancement Project Power Transmission and Distribution System Strengthening PTDSSP Project ROW right of way SASEC South Asia Sub-regional Economic Cooperation SF6 sulfur hexafluoride SNNP Shivapuri Nagarjun National Park SPCC spill prevention control and countermeasures UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization WEIGHTS AND MEASURES ha – hectare amp - ampere Hz - hertz km – kilometer (1,000 meters) kV – kilovolt (1,000 volts) kW – kilowatt (1,000 watts) mG - milligauss NOTES In this report, "$" refers to US dollars unless otherwise stated. -

Rutschungen Im Südwestlichen Annapurna-Massiv Des Zentralen Nepal-Himalaya

Rutschungen im südwestlichen Annapurna-Massiv des zentralen Nepal-Himalaya Ein Beitrag zur geographischen Hazardforschung Peter Christian Ottinger I N A U G U R A L - D I S S E R T A T I O N zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Naturwissenschaftlich-Mathematischen Gesamtfakultät der Ruprecht - Karls - Universität Heidelberg Gutachter: HD Dr. Dietrich Schmidt-Vogt Prof. Dr. Edmund Krauter vorgelegt von Diplom-Geograph Peter Christian Ottinger aus Rosenberg in Oberschlesien April 2003 I Vorwort Bereits auf Reisen 1995, 1996 und 1997 in verschiedene Landesteile Nepals reifte in mir die Idee, über Naturgefahren im Himalaya eine Arbeit zu verfassen. Die hochentwickelte Terrassenlandwirtschaft an den steilen Hängen im nepalischen Bergland faszinierte mich von Anfang an. Ist sie jedoch nicht stark bedroht durch die heftigen Monsunregen, Erdbeben und Rutschungen? Ich konnte doch so häufig Abrißnischen von Rutschungen, Murkegel und Spuren von Überflutungen mitten in bewohnten Gebieten sehen. Dieser Frage wollte ich nachgehen und über die Naturgefahren, allen voran über die Rutschungen in dem dicht besiedelten Gebirgsraum mehr herausfinden. Ein heftiger Sommermonsun des Jahres 1998 mit zahlreichen frischen Rutschungen veranlaßte mich schließlich, mit meinem physio- geographischen Hintergrund und einigen Erfahrungen aus den europäischen Hochgebirgen diese anspruchsvolle Aufgabe anzugehen. Zur Entstehung dieser Arbeit haben eine Vielzahl von Personen beigetragen. Mein ganz besonderer Dank gilt meinem Doktorvater Herrn HD Dr. Dietrich Schmidt-Vogt, der die Arbeit bestens betreut hat und mir jederzeit beratend und engagiert zur Stelle stand, in Nepal wie in Heidelberg. Durch seine große Nepalerfahrung öffnete er mir die Augen für das Verständnis des Landes und seiner Menschen sowie die geoökologischen Zusammenhänge. -

Ecotourism in Annapurna Conservation Area: Potential, Opportunities and Challenges

Grassroots Journal of Natural Resources, Vol. 3 No. 4 (2020) http://journals.grassrootsinstitute.net/journal1-natural-resources/ ISSN: 2581-6853 | Doi: 10.33002 | Published by Grassroots Institute Research Article Ecotourism in Annapurna Conservation Area: Potential, Opportunities and Challenges Bishow Poudel1, Rajeev Joshi*1, 2 1Faculty of Forestry, Amity Global Education (Lord Buddha College), CTEVT, Tokha-11, Kathmandu- 44600, Nepal 2Forest Research Institute (Deemed to be) University, Dehradun-248195, Uttarakhand, India *Corresponding author: [email protected] | ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1106-9911 How to cite this paper: Poudel, B. and Abstract Joshi, R. (2020). Ecotourism in Annapurna Conservation Area: Potential, Opportunities Ecotourism as a component of the sustainable green and Challenges. Grassroots Journal of economy is one of the fastest growing segments of the Natural Resources, 3(4): 49-73. Doi: tourism industry, because of its superiority compared to https://doi.org/10.33002/nr2581.6853.03044 other types of tourism in terms of the responsibility towards people, nature and environment. In the long run, people can also be benefitted from ecotourism. This research explores the fundamental potential, challenges and opportunities of Received: 22 September 2020 developing ecotourism in Ghorepani village of Annapurna Reviewed: 14 October 2020 Conservation Area (ACA), the first and largest Provisionally Accepted: 19 October 2020 mountainous protected area in Nepal. Primary data were Revised: 01 November 2020 Finally Accepted: 18 November 2020 collected through preliminary field visit, questionnaire Published: 20 December 2020 survey of households, key informant interviews, focus Copyright © 2020 by author(s) group discussion and direct field observation. The Ghorepani village of ACA attracts many tourists because of its beautiful natural landscape, biodiversity richness, This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International snow-capped mountains, sunrise from Poon hills and License (CC BY 4.0). -

Overview Outline Itinerary

Khair or Khayer Lake Trek Overview Khayer Lake Trek is newly discovered alternative trekking trail in Annapurna region situated between classic Annapurna Base Camp and Jomsom trekking trail. It is a newly promoted beautiful Trekking route with mix culture of Gurung and Magar people and exceptional mountain views over the many Himalayas including Mt. Dhaulagiri, Annapurna and Nilgiri from Khopra Ridge and Poon Hill. Beside the scenic variety of the peaks, the warm hospitality of the Gurung people along the way of Khair Lake Trekking is well off the beaten trail in Annapurna Region, on too long, remote mountain ridges, through rhododendron forest and to visit traditional villages. From Pokhara our Trip starts in the lower, more temperate region of forested hillsides and Gurung and Magar villages. As we move higher through the rhododendron woodlands the views of Annapurna South, Hiunchuli and Machhapuchhre are beyond your belief. On reaching Khopra Ridge our encampment is right below Mt. Annapurna. From here we walk up to the sacred lake above Khair, offering a marvelous alpine experience. On the way trek back to Pokhara; we follow main Ghorepani Poon Hill Trek and ABC Trek itinerary for one of the most famous panoramas in the Annapurna area or we have alternative trail to head down to Tatopani from Khopra ridge which lies on the way to Jomsom Muktinath Trek or Annapurna Circuit Trail part two. At Tatopani we can enjoy the ‘natural hot spring’ healing bathe and a drink and end our trek then drive back to Pokhara. Outline Itinerary Day 01 : Ride tourist bus to Pokhara from Kathmandu.