University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Last Stardust Mp3 다운

Last stardust mp3 다운 Continue He online Bei Hut Last Stardust do sĩ Aimer thể hiện. Original artist: Aimer Stream without advertising or buying CDs and MP3s is currently Amazon.com. Stardust. by Aimer on Midnight Sun. Aimer-Last Stardust.mp3为百度云⽹盘资源搜索结果,Aimer-Last Stardust.mp3下载是直接跳转到百度云⽹盘,Aimer- Last Stardust.mp3⽂件的安全性和完整性需要您⾃⾏判断。 Download. Ka Khek Last Stardust do sĩ Aymer thể hiện, thuộc thể loại Nhạc Nhật.C'c bạn se thể nghe, download (tải nhạc) bei h't last star dust mp3, playlist/album, MV/Video of the latest stardust miễn ph' tại NhacCuaTui.com. Check out The Last Stardust by Aimer on Amazon Music. , Aimer - The Last Stardust Google Drive, download anime mp3 Aimer - Last discovery Stardust, Download OST Destiny / Stay Night: Unlimited Blade runs full Mp3 320kbps, Download Lagu Aimer - Latest Stardust Full Mp3 320kbps Download. Free Aimer Last Stardust Full mp3 Play. 4:44 Listen now $1.29 In... Eimer's last Stardust at dawn. Dust in dust, ashes in ashes, fragments of desires, reach the far! Aimer (エメ, pronounced da-mech), born July 9, 1990 in Kumamoto, Japan, is a Japanese recording artist signed to Sony Music Entertainment Japan and is attached to talent agency FOURseam. Free Destiny Stay night Unlimited Blade runs Ep 20 LAST STARDUST Aimer W Texts mp3 Play. Watch the video for Kataomoi from The Best Choice Aymer Blanc for free, and see works of art, lyrics and similar artists. STARDUST DESCARGAR MP3: Escucha la mejor musica en linea, descarga mi de mp3 gratis, Musica' es Musica de Calidad: Canciones de Stardust .. -

Kretan Cult and Customs, Especially in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods: a Religious, Social, and Political Study

i Kretan cult and customs, especially in the Classical and Hellenistic periods: a religious, social, and political study Thesis submitted for degree of MPhil Carolyn Schofield University College London ii Declaration I, Carolyn Schofield, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been acknowledged in the thesis. iii Abstract Ancient Krete perceived itself, and was perceived from outside, as rather different from the rest of Greece, particularly with respect to religion, social structure, and laws. The purpose of the thesis is to explore the bases for these perceptions and their accuracy. Krete’s self-perception is examined in the light of the account of Diodoros Siculus (Book 5, 64-80, allegedly based on Kretan sources), backed up by inscriptions and archaeology, while outside perceptions are derived mainly from other literary sources, including, inter alia, Homer, Strabo, Plato and Aristotle, Herodotos and Polybios; in both cases making reference also to the fragments and testimonia of ancient historians of Krete. While the main cult-epithets of Zeus on Krete – Diktaios, associated with pre-Greek inhabitants of eastern Krete, Idatas, associated with Dorian settlers, and Kretagenes, the symbol of the Hellenistic koinon - are almost unique to the island, those of Apollo are not, but there is good reason to believe that both Delphinios and Pythios originated on Krete, and evidence too that the Eleusinian Mysteries and Orphic and Dionysiac rites had much in common with early Kretan practice. The early institutionalization of pederasty, and the abduction of boys described by Ephoros, are unique to Krete, but the latter is distinct from rites of initiation to manhood, which continued later on Krete than elsewhere, and were associated with different gods. -

This Thesis Comes Within Category D

* SHL ITEM BARCODE 19 1721901 5 REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year i ^Loo 0 Name of Author COPYRIGHT This Is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London, it is an unpubfished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the .premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 -1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 -1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

Ovid Book 12.30110457.Pdf

METAMORPHOSES GLOSSARY AND INDEX The index that appeared in the print version of this title was intentionally removed from the eBook. Please use the search function on your eReading device to search for terms of interest. For your reference, the terms that ap- pear in the print index are listed below. SINCE THIS index is not intended as a complete mythological dictionary, the explanations given here include only important information not readily available in the text itself. Names in parentheses are alternative Latin names, unless they are preceded by the abbreviation Gr.; Gr. indi- cates the name of the corresponding Greek divinity. The index includes cross-references for all alternative names. ACHAMENIDES. Former follower of Ulysses, rescued by Aeneas ACHELOUS. River god; rival of Hercules for the hand of Deianira ACHILLES. Greek hero of the Trojan War ACIS. Rival of the Cyclops, Polyphemus, for the hand of Galatea ACMON. Follower of Diomedes ACOETES. A faithful devotee of Bacchus ACTAEON ADONIS. Son of Myrrha, by her father Cinyras; loved by Venus AEACUS. King of Aegina; after death he became one of the three judges of the dead in the lower world AEGEUS. King of Athens; father of Theseus AENEAS. Trojan warrior; son of Anchises and Venus; sea-faring survivor of the Trojan War, he eventually landed in Latium, helped found Rome AESACUS. Son of Priam and a nymph AESCULAPIUS (Gr. Asclepius). God of medicine and healing; son of Apollo AESON. Father of Jason; made young again by Medea AGAMEMNON. King of Mycenae; commander-in-chief of the Greek forces in the Trojan War AGLAUROS AJAX. -

Argumentative Euphemisms, Political Correctness and Relevance

Argumentative Euphemisms, Political Correctness and Relevance Thèse présentée à la Faculté des lettres et sciences humaines Institut des sciences du langage et de la communication Université de Neuchâtel Pour l'obtention du grade de Docteur ès Lettres Par Andriy Sytnyk Directeur de thèse: Professeur Louis de Saussure, Université de Neuchâtel Rapporteurs: Dr. Christopher Hart, Senior Lecturer, Lancaster University Dr. Steve Oswald, Chargé de cours, Université de Fribourg Dr. Manuel Padilla Cruz, Professeur, Universidad de Sevilla Thèse soutenue le 17 septembre 2014 Université de Neuchâtel 2014 2 Key words: euphemisms, political correctness, taboo, connotations, Relevance Theory, neo-Gricean pragmatics Argumentative Euphemisms, Political Correctness and Relevance Abstract The account presented in the thesis combines insights from relevance-theoretic (Sperber and Wilson 1995) and neo-Gricean (Levinson 2000) pragmatics in arguing that a specific euphemistic effect is derived whenever it is mutually manifest to participants of a communicative exchange that a speaker is trying to be indirect by avoiding some dispreferred saliently unexpressed alternative lexical unit(s). This effect is derived when the indirectness is not conventionally associated with the particular linguistic form-trigger relative to some context of use and, therefore, stands out as marked in discourse. The central theoretical claim of the thesis is that the cognitive processing of utterances containing novel euphemistic/politically correct locutions involves meta-representations of saliently unexpressed dispreferred alternatives, as part of relevance-driven recognition of speaker intentions. It is argued that hearers are “invited” to infer the salient dispreferred alternatives in the process of deriving explicatures of utterances containing lexical units triggering euphemistic/politically correct interpretations. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

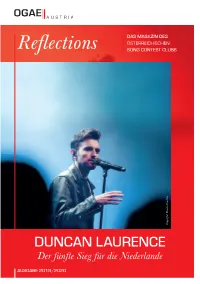

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

Popmusik Musikgruppe & Musisk Kunstner Listen

Popmusik Musikgruppe & Musisk kunstner Listen Stacy https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/stacy-3503566/albums The Idan Raichel Project https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/the-idan-raichel-project-12406906/albums Mig 21 https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/mig-21-3062747/albums Donna Weiss https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/donna-weiss-17385849/albums Ben Perowsky https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ben-perowsky-4886285/albums Ainbusk https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ainbusk-4356543/albums Ratata https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ratata-3930459/albums Labvēlīgais Tips https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/labv%C4%93l%C4%ABgais-tips-16360974/albums Deane Waretini https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/deane-waretini-5246719/albums Johnny Ruffo https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/johnny-ruffo-23942/albums Tony Scherr https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/tony-scherr-7823360/albums Camille Camille https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/camille-camille-509887/albums Idolerna https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/idolerna-3358323/albums Place on Earth https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/place-on-earth-51568818/albums In-Joy https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/in-joy-6008580/albums Gary Chester https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/gary-chester-5524837/albums Hilde Marie Kjersem https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/hilde-marie-kjersem-15882072/albums Hilde Marie Kjersem https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/hilde-marie-kjersem-15882072/albums -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Silencing the Female Voice in Longus and Achilles Tatius

Silencing the female voice in Longus and Achilles Tatius Word Count: 12,904 Exam Number: B052116 Classical Studies MA (Hons) School of History, Classics and Archaeology University of Edinburgh B052116 Acknowledgments I am indebted to the brilliant Dr Calum Maciver, whose passion for these novels is continually inspiring. Thank you for your incredible supervision and patience. I’d also like to thank Dr Donncha O’Rourke for his advice and boundless encouragement. My warmest thanks to Sekheena and Emily for their assistance in proofreading this paper. To my fantastic circle of Classics girls, thank you for your companionship and humour. Thanks to my parents for their love and support. To Ben, for giving me strength and light. And finally, to the Edinburgh University Classics Department, for a truly rewarding four years. 1 B052116 Table of Contents Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………….1 List of Abbreviations………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter 1: Through the Male Lens………………………………………………………6 The Aftertaste of Sophrosune……………………………………………………………….6 Male Viewers and Voyeuristic Fantasy.…………………………………………………....8 Narratorial Manipulation of Perspective………………………………………………….11 Chapter 2: The Mythic Hush…………………………………………………………….15 Echoing Violence in Longus……………………………………………………………….16 Making a myth out of Chloe………………………………………………………………..19 Leucippe and Europa: introducing the mythic parallel……………………………………21 Andromeda, Philomela and Procne: shifting perspectives………………………………...22 Chapter 3: Rupturing the -

Calasiris the Pseudo-Greek Hero: Odyssean Allusions in Heliodorus' Aethiopica

Calasiris the Pseudo-Greek Hero: Odyssean Allusions in Heliodorus' Aethiopica Christina Marie Bartley A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master’s degree in Classical Studies Department of Classics and Religious Studies Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Christina Marie Bartley, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 Table of Contents Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................... iii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... vii Introduction ..................................................................................................................... viii 1. The Structural Markers of the Aethiopica .......................................................................1 1.1.Homeric Strategies of Narration ..........................................................................................2 1.1.1. In Medias Res .................................................................................................................3 1.2. Narrative Voices .................................................................................................................8 1.2.1. The Anonymous Primary Narrator ................................................................................9 1.2.2. Calasiris........................................................................................................................10 -

Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath from a Kristevan Perspective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository Transforming the Law of One: Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath from a Kristevan Perspective A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Areen Ghazi Khalifeh School of Arts, Brunel University November 2010 ii Abstract A recent trend in the study of Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath often dissociates Confessional poetry from the subject of the writer and her biography, claiming that the artist is in full control of her work and that her art does not have naïve mimetic qualities. However, this study proposes that subjective attributes, namely negativity and abjection, enable a powerful transformative dialectic. Specifically, it demonstrates that an emphasis on the subjective can help manifest the process of transgressing the law of One. The law of One asserts a patriarchal, monotheistic law as a social closed system and can be opposed to the bodily drives and its open dynamism. This project asserts that unique, creative voices are derived from that which is individual and personal and thus, readings of Confessional poetry are in fact best served by acknowledgment of the subjective. In order to stress the subject of the artist in Confessionalism, this study employed a psychoanalytical Kristevan approach. This enables consideration of the subject not only in terms of the straightforward narration of her life, but also in relation to her poetic language and the process of creativity where instinctual drives are at work. This study further applies a feminist reading to the subject‘s poetic language and its ability to transgress the law, not necessarily in the political, macrocosmic sense of the word, but rather on the microcosmic, subjective level.