Illinois Classical Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poems of Catullus As They Went to the Printer for the first Time, in Venice 400 Years Ago

1.Catullus, Poems 1/12/05 2:52 PM Page 1 INTRODUCTION LIFE AND BACKGROUND We know very little for certain about Catullus himself, and most of that has to be extrapolated from his own work, always a risky procedure, and nowadays with the full weight of critical opinion against it (though this is always mutable, and there are signs of change in the air). On the other hand, we know a great deal about the last century of the Roman Republic, in which his short but intense life was spent, and about many of the public figures, both literary and political, whom he counted among his friends and enemies. Like Byron, whom in ways he resembled, he moved in fashionable circles, was radical without being constructively political, and wrote poetry that gives the overwhelming impression of being generated by the public aªairs, literary fashions, and aristocratic private scandals of the day. How far all these were fictionalized in his poetry we shall never know, but that they were pure invention is unlikely in the extreme: what need to make up stories when there was so much splendid material to hand? Obviously we can’t take what Catullus writes about Caesar or Mamurra at face value, any more than we can By- ron’s portraits of George III and Southey in “The Vision of Judgement,” or Dry- den’s of James II and the Duke of Buckingham in “Absalom and Achitophel.” Yet it would be hard to deny that in every case the poetic version contained more than a grain of truth. -

Attis and Lesbia: Catullus' Attis Poem As Symbolic Reflection of the Lesbia

71-7460 GENOVESE, Jr., Edgar Nicholas, 1942- ATTIS AND LESBIA; CATULLUS’ ATTIS POEM AS A SYMBOLIC REFLECTION OF THE LESBIA CYCLE. iPortions of Text in Greek and Latin]. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1970 Language and Literature, classical • University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Edgar Nicholas Genovese, Jr. 1971 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED ATTIS AND LESBIA: CATULLUS' ATTIS POEM AS A SYMBOLIC REFLECTION OF THE LESBIA CYCLE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Hie Ohio State University By Edgar Nicholas Genovese, Jr., A.B. The Ohio State University 1970 Approved by ^ \ Adviser Dc^^rtment of Classics ACKNOWLEDGMENTS John T. Davis, cui maximas gratias ago, mentem meam ducebat et ingenium dum hoc opusculum fingebam; multa autern addiderunt atque cor- rexerunt Clarence A. Forbes et Vincent J. Cleary, quibus ago gratias. poetam uero Veronensem memoro laudoque. denique admiror gratam coniugem meam ac diligo: quae enim, puellula nostra mammam appetente, ter adegit manibus suis omnes litteras in has paginas. ii PARENTIBVS MEIS XXX VITA September 18, 1942 . Born— Baltimore, Maryland 1960-1964 .............. A.B., Classics, Xavier University, Cincinnati, Ohio 1964-1966 .............. Instructor, Latin, Kenwood Senior High School, Baltimore, Maryland 1966-1968 .............. Teaching Assistant, Teaching Associate, Department of Classics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio Summer 1968 ............ Instructor, Elementary Greek, Department of Classics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1968-1970 ........ N.D.E.A. Fellow, Department of Classics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio Summer 1969, 1970 . Assistant, Latin Workshop, Department of Classics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio FIELDS OF STUDY Major field; Latin and Greek poetry Latin literature. -

Catullus in Verona Skinner FM 3Rd.Qxd 9/22/2003 11:39 AM Page Ii Skinner FM 3Rd.Qxd 9/22/2003 11:39 AM Page Iii

Skinner_FM_3rd.qxd 9/22/2003 11:39 AM Page i Catullus in Verona Skinner_FM_3rd.qxd 9/22/2003 11:39 AM Page ii Skinner_FM_3rd.qxd 9/22/2003 11:39 AM Page iii Catullus in Verona A Reading of the Elegiac Libellus, Poems 65–116 MARILYN B. SKINNER The Ohio State University Press Columbus Skinner_FM_3rd.qxd 9/22/2003 11:39 AM Page iv Copyright © 2003 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Skinner, Marilyn B. Catullus in Verona : a reading of the elegiac libellus, poems 65-116 / Marilyn B. Skinner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8142-0937-8 (Hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-9023- X (CD-ROM) 1. Catullus, Gaius Valerius. Carmen 65-116. 2. Catullus, Gaius Valerius—Knowledge—Verona (Italy) 3. Elegiac poetry, Latin— History and criticism. 4. Verona (Italy)—In literature. I. Title. PA6276 .S575 2003 874'.01—dc21 2003004754 Cover design by Dan O’Dair. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Skinner_FM_3rd.qxd 9/22/2003 11:39 AM Page v D. M. parentibus carissimis Edwin John Berglund, 1903–1993 Marie Michalsky Berglund, 1905–1993 hoc vobis quod potui Skinner_FM_3rd.qxd 9/22/2003 11:39 AM Page vi Skinner_FM_3rd.qxd 9/22/2003 11:39 AM Page vii Ghosts Those houses haunt in which we leave Something undone. -

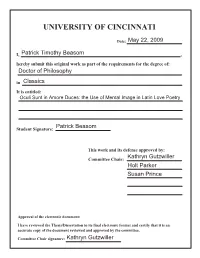

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 22, 2009 I, Patrick Timothy Beasom , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Oculi Sunt in Amore Duces: the Use of Mental Image in Latin Love Poetry Patrick Beasom Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Kathryn Gutzwiller Holt Parker Susan Prince Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Kathryn Gutzwiller Oculi Sunt in Amore Duces: The Use of Mental Image in Latin Love Poetry A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick Timothy Beasom B.A., University of Richmond, 2002 M.A., University of Cincinnati, 2006 May 2009 Committee Chair: Kathryn Gutzwiller, Ph.D. Abstract Propertius tells us that the eyes are our guides in love. Both he and Ovid enjoin lovers to keep silent about their love affairs. I explore the ability of poetry to make our ears and our eyes guides, and, more importantly, to connect seeing and saying, videre and narrare. The ability of words to spur a reader or listener to form mental images was long recognized by Roman and Greek rhetoricians. This project takes stock for the first time of how poets, three Roman love poets, in this case, applied vivid description and other rhetorical devices to spur their readers to form mental images of the love they read. -

Conflicting Identities and Gender Construction in the Catullan Corpus Rebecca F

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Classics Honors Projects Classics Department Spring 5-6-2014 Eros the Man, Eros the Woman: Conflicting Identities and Gender Construction in the Catullan Corpus Rebecca F. Boylan Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Boylan, Rebecca F., "Eros the Man, Eros the Woman: Conflicting Identities and Gender Construction in the Catullan Corpus" (2014). Classics Honors Projects. Paper 18. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors/18 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eros the Man, Eros the Woman: Conflicting Identities and Gender Construction in the Catullan Corpus By Rebecca Boylan Professor Brian Lush, Advisor Macalester College Classics Department Submitted May 6, 2014 Boylan 1 To Grandma, who taught me the value of education and persistence Ave atque vale Boylan 2 We hear a good deal from Catullus about his joys, griefs, and passions, but in the end we have hardly any idea of what he was really like. Richard Jenkyns, Three Classical Poets, 84 Boylan 3 Table of Contents Section I: Catullus’ Rome ...............................................................................................................5 -

GOETTING, CODY WALTER, MA DECEMBER 2019 LATIN the VOICES of WOMEN in LATIN ELEGY (67 Pp.)

GOETTING, CODY WALTER, M.A. DECEMBER 2019 LATIN THE VOICES OF WOMEN IN LATIN ELEGY (67 pp.) Thesis Adviser: Dr. Jennifer Larson By examining feminine speech within the corpus of love elegies composed throughout the Augustan period, especially those written by Tibullus, Sulpicia, Propertius, and Ovid, one can determine various stylistic uses of female characters within the entire corpus. In addition to this, while his writings were penned a generation before the others, the works of Catullus will be examined as well, due to the influence his works had on the Augustan Elegists. This examination will begin identifying and detailing every instance of speech within the elegies from a female source, and exploring when, how, and why they are used. The majority of the elegies in which these instances occur are briefer, more veristic in nature, although longer, more polished examples exist as well; both types are examined. Except for Sulpicia, these poets are male and present the majority of their elegies from a masculine point of view; this influence is also examined. THE VOICES OF WOMEN IN LATIN ELEGY A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Cody Goetting December 2019 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Cody Walter Goetting B.S., Bowling Green State University, 2013 B.S., Bowling Green State University, 2013 M.A., Kent State University, 2019 Approved by ________________________________, Advisor Dr. Jennifer Larson ________________________________, Chair, Department of Modern and Classical Languages Dr. Keiran Dunne ________________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Dr. -

A Study of the Political and Social Conditions of Rome As Reflected in the Oetrp Y of the Four Great Lyricists, Catullus, Tibullus, Propertius and Horace

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1940 A Study of the Political and Social Conditions of Rome as Reflected in the oetrP y of the Four Great Lyricists, Catullus, Tibullus, Propertius and Horace. Augusta Maupin Porter College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Porter, Augusta Maupin, "A Study of the Political and Social Conditions of Rome as Reflected in the oetrP y of the Four Great Lyricists, Catullus, Tibullus, Propertius and Horace." (1940). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1593092113. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/m2-669a-9y72 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS OF ROME AS REFLECTED IN THE POETRY OF THE FOUR GREAT LYRICISTS: CATULLUS, TIBULLUS, PROPERTIUS, AND HORACE W Augusta Maupin Porter A STUDY OF THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS OF ROME AS REFLECTED IN THE POETRY OF THE FOUR GREAT LYRICISTS: CATULLUS, TIBULLUS, PROPERTIUS, AND HORACE W Augusta Maupin Porter SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY for the degree MASTER OF ARTS 1940 TABLE OF CONTENTS -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 11 December 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Ingleheart, J. (2014) 'Play on the proper names of individuals in the Catullan corpus : wordplay, the iambic tradition, and the late Republican culture of public abuse.', Journal of Roman studies., 104 . pp. 51-72. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0075435814000069 Publisher's copyright statement: Copyright c The Author(s) 2014. Published by The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. This paper has been published in a revised form, subsequent to editorial input by Cambridge University Press, in 'Journal of Roman studies' (104: (November 2014) 51-72) http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=JRS Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Play -

Invective Drag: Talking Dirty in Catullus, Cicero, Horace, and Ovid Casey Catherine Moore University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 12-14-2015 Invective Drag: Talking Dirty in Catullus, Cicero, Horace, and Ovid Casey Catherine Moore University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Moore, C. C.(2015). Invective Drag: Talking Dirty in Catullus, Cicero, Horace, and Ovid. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3265 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVECTIVE DRAG: TALKING DIRTY IN CATULLUS, CICERO, HORACE, AND OVID by Casey Catherine Moore Bachelor of Arts University of South Florida, 2007 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2010 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Paul Allen Miller, Major Professor Hunter H. Gardner, Committee Member Mark A. Beck, Committee Member David Lee Miller, Committee Member Ed Gieskes, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Casey Catherine Moore, 2015 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have been very fortunate to have had a phenomenal support system throughout the dissertation process. I am incredibly thankful for my advisor, Paul Allen Miller, whose guidance, comprehensive feedback, and high expectations made for a dissertation I am proud of. Through taking Allen’s courses, working with him at TAPA, and his guidance throughout the comprehensive exam, prospectus, and dissertation, I have remained inspired by him and grateful for so excellent a mentor. -

Exploring the Classical World Catullus - Political Worlds

Exploring the classical world Catullus - political worlds Paula So you were becoming more intrigued by the political elements of the poem and what kind of conclusions we could draw from these. And very importantly and controversially whether Catullus’ poetry could be mined for information on the political and social scene of the late Republic. You mentioned Clodius and Caelius. Tell us a bit more about the political elements of the poems in which they appear. Is that a major message? Kate It’s definitely part of the message. How major is difficult to tell. I don’t want to forget the actual poetry of Catullus and this poem is a prime example of how Catullus gets his message across, both through his sound effects and through the actual words he uses. It’s only a short poem and I’d like just to have a look at some of the lines of it. You start off: Caeli, Lesbia nostra, Lesbia illa. Illa Lesbia, quam Catullan unam…etc How many times have you got Lesbia mentioned? Three times in two lines. You’ve got Caelius at the beginning, Catullus at the end, Lesbia in the middle. So you’ve got the rivals on either side of her with her in the middle. You’ve got that Caiasmus Lesbia illa, illa Lesbia. And then you’ve got all these sound effects which are wonderful. We start off with all these long sounds, Caeli, Lesbia, nostra, Lesbia illa. Euphonic sounds to the Romans, they liked As and Os and Us, naturally long accents. -

Introduction: the Young Poet in Rome

1 Introduction: The Young Poet in Rome Romae vivimus: illa domus, illa mihi sedes, illic mea carpitur aetas. (Poem 68.34–5) Catullus is the most accessible of the ancient poets. His poems (even the very long ones) convey an emotional immediacy and urgency that claim the reader’s sympathy. The emotions themselves—love, sorrow, pleasure, hatred, contempt—are clear, direct, passionate, very much like our own, we are tempted to imagine. They are set out for us not in the abstract but in the real, historical world of late republican Rome. This Rome, evoked for us with a few light, sharp strokes, is a virtual character in the poetry, with its politicians, playboys (and girls), low-lifes, and fellow poets. Catullus’ language seems for the most part as clear and direct as his feelings. His characteristic meter, the phalaecean hendecasyllabic, is relaxed, conversational, and memorable. He is learned (formidably so), but a first reader does not have to be equally learned in order to respond to him. Many of his poems are short of fewer than 20 lines, so that even a novice Latinist can take them in at a sitting. But Catullus’ accessibility is deceiving. He draws us into his world and its emotional landscape so artfully that we think we know him much better than we do, rather like a seemingly open and guileless acquaintance we have known for a time and then realized we did not know at all. The emotional immediacy and factual details in Catullus’ poems can make us forget that his poetry, like all poetry, is a fiction. -

Reading Propertius

Foreword READING PROPERTIUS MATTHEW S. SANTIROCCO I Quot editores, tot Propertii. The learned quip—“There are as many Propertiuses as there are editors”—refers to the notorious unreliability of the Latin text and to the ingenuity of such schol- ars as A. E. Housman who have tried to emend and restore it. But the phrase could apply just as easily to the wide variety of literary interpretations, equally ingenious and often incompat- ible, that Propertius’ love elegies have provoked over the cen- turies. Writing in the Rome of the emperor Augustus toward the end of the first century b.c.e., Sextus Propertius captured and critiqued the experience of a generation that had lived through civil wars only to have peace restored at the expense of repub- lican government, a generation for whom personal desires were often at odds with public duty and for whom the demands of aesthetics could be as urgent and morally compelling as political ix x/Foreword necessities. In his own day, Propertius would have us believe, he was something of a scandal (Elegy II.24a.1–8). Several years later, the rhetorician Quintilian admired the elegies of Tibullus for their terseness and elegance (qualities that would appeal to a rhetorician), and only grudgingly admitted that “there are those who prefer Propertius” (Institutes of Oratory 10.1.93). By the Christian Middle Ages, the elegist was virtually unknown, perhaps owing to the immorality or at least perceived irrele- vance of his sort of poetry. The earliest manuscript we have dates to around 1200; and it was only later, particularly in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, that texts of Propertius cir- culated and he was rediscovered by readers.