Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Military Service in the Second World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

27 May 2020 Ordinary Council Meeting Agenda

Ordinary Council Meeting 27 May 2020 Council Chambers, Town Hall, Sturt Street, Ballarat AGENDA Public Copy Ordinary Council Meeting Agenda 27 May 2020 NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT A MEETING OF BALLARAT CITY COUNCIL WILL BE HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, TOWN HALL, STURT STREET, BALLARAT ON WEDNESDAY 27 MAY 2020 AT 7:00PM. This meeting is being broadcast live on the internet and the recording of this meeting will be published on council’s website www.ballarat.vic.gov.au after the meeting. Information about the broadcasting and publishing recordings of council meetings is available in council’s broadcasting and publishing recordings of council meetings procedure available on the council’s website. AGENDA ORDER OF BUSINESS: 1. Opening Declaration........................................................................................................4 2. Apologies For Absence...................................................................................................4 3. Disclosure Of Interest .....................................................................................................4 4. Confirmation Of Minutes.................................................................................................4 5. Matters Arising From The Minutes.................................................................................4 6. Public Question Time......................................................................................................5 7. Reports From Committees/Councillors.........................................................................6 -

Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative : a Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative: A Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand Soldier David Guerin 94114985 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Arts Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand (Cover) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). (Above) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 2/1498, New Zealand Field Artillery, First New Zealand Expeditionary Force, 1915, left, & 1917, right. 2 Dedication Dedicated to: Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 1893 ̶ 1962, 2/1498, NZFA, 1NZEF; Alexander John McKay Manson, 11/1642, MC, MiD, 1895 ̶ 1975; John Guerin, 1889 ̶ 1918, 57069, Canterbury Regiment; and Christopher Michael Guerin, 1957 ̶ 2006; And all they stood for. Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). 3 Acknowledgements Distinguished Professor Sally J. Morgan and Professor Kingsley Baird, thesis supervisors, for their perseverance and perspicacity, their vigilance and, most of all, their patience. With gratitude and untold thanks. All my fellow PhD candidates and staff at Whiti o Rehua/School of Arts, and Toi Rauwhārangi/ College of Creative Arts, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa o Pukeahu Whanganui-a- Tara/Massey University, Wellington, especially Jess Richards. -

Day of Mourning – Overview Fact Sheet

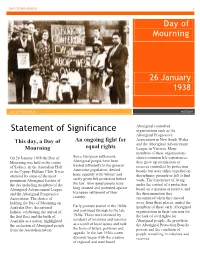

DAY OF MOURNING 1 Day of Mourning 26 January 1938 DAY OF MOURNING HISTORY Aboriginal controlled Statement of Significance organisations such as the Aboriginal Progressive Association in New South Wales An ongoing fight for This day, a Day of and the Aboriginal Advancement Mourning equal rights League in Victoria. Many members of these organisations On 26 January 1938 the Day of Since European settlement, shared common life experiences; Mourning was held in the centre Aboriginal people have been they grew up on missions or of Sydney, in the Australian Hall treated differently to the general reserves controlled by protection at the Cyprus Hellene Club. It was Australian population; denied boards but were either expelled on attended by some of the most basic equality with 'whites' and disciplinary grounds or left to find prominent Aboriginal leaders of rarely given full protection before work. The experience of living the day including members of the the law. Aboriginal people have under the control of a protection Aboriginal Advancement League long resisted and protested against board on a mission or reserve, and and the Aboriginal Progressive European settlement of their the discrimination they Association. The choice of country. encountered when they moved holding the Day of Mourning on away from these places, united the Australia Day, the national Early protests started in the 1840s members of these early Aboriginal holiday celebrating the arrival of and continued through to the late organisations in their concerns for the first fleet and the birth of 1920s. These were initiated by the lack of civil rights for Australia as a nation, highlighted residents of missions and reserves Aboriginal people, the growth in the exclusion of Aboriginal people as a result of local issues and took the Aboriginal Protection Board's from the Australian nation. -

Patrick Stevedores Port Botany Container Terminal Project Section 75W Modification Application December 2012

Patrick Stevedores Operations No. 2 Patrick Stevedores Port Botany Container Terminal Project Section 75W Modification Application December 2012 Table of contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The proponent ................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 The site ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Project context ................................................................................................................ 4 1.5 Document structure ......................................................................................................... 5 2. Project description ..................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Key aspects of the project ............................................................................................... 6 2.2 Demolition, enabling and construction works ................................................................. 10 2.3 Operation ...................................................................................................................... 12 2.4 Construction workforce and working hours.................................................................... -

Australia's National Heritage

AUSTRALIA’S australia’s national heritage © Commonwealth of Australia, 2010 Published by the Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts ISBN: 978-1-921733-02-4 Information in this document may be copied for personal use or published for educational purposes, provided that any extracts are fully acknowledged. Heritage Division Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Email [email protected] Phone 1800 803 772 Images used throughout are © Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and associated photographers unless otherwise noted. Front cover images courtesy: Botanic Gardens Trust, Joe Shemesh, Brickendon Estate, Stuart Cohen, iStockphoto Back cover: AGAD, GBRMPA, iStockphoto “Our heritage provides an enduring golden thread that binds our diverse past with our life today and the stories of tomorrow.” Anonymous Willandra Lakes Region II AUSTRALIA’S NATIONAL HERITAGE A message from the Minister Welcome to the second edition of Australia’s National Heritage celebrating the 87 special places on Australia’s National Heritage List. Australia’s heritage places are a source of great national pride. Each and every site tells a unique Australian story. These places and stories have laid the foundations of our shared national identity upon which our communities are built. The treasured places and their stories featured throughout this book represent Australia’s remarkably diverse natural environment. Places such as the Glass House Mountains and the picturesque Australian Alps. Other places celebrate Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture—the world’s oldest continuous culture on earth—through places such as the Brewarrina Fish Traps and Mount William Stone Hatchet Quarry. -

Australian Hall

150-2 ELIZABETH ST, SYDNEY 1 Australian Hall 150-2 Elizabeth St Sydney 150-2 ELIZABETH ST, SYDNEY HISTORY Knights of the Southern Cross, a Statement of Significance Catholic fraternal lay group linked with the Catholic Right and, The Australian Hall holds social William Ferguson ultimately with the split in the significance for at least three Tom Foster Labor Party in the 1950s. groups of people. Pearl Gibbs The building was initially built to Helen Grosvenor Firstly, the building holds social be used as a meeting place for Jack Johnson significance for the Aboriginal cultural and social activities and People for its role in the 1938 Jack Kinchela was continuously used for these "Day of Mourning" meeting. Bert Marr events including cinema and Pastor Doug Nicholls theatre. It is a rare example of a This event was the first protest by Henry Noble purpose built building in Sydney Aboriginal people for equal Jack Patten continuously used for its initial opportunities within Australian Tom Pecham purpose. Society. It was attended by Frank Roberts approximately 100 people of Margaret Tucker The building holds architectural Aboriginal Blood and was the significance as it still contains beginning of the contemporary Secondly, it holds significance for some examples of original Aboriginal Political Movement. the German and Greek-Cypriot architecture. It is a good example Among those who contributed communities in Sydney as it of the Federation Romanesque significantly to the movement allowed visitors and migrants to style. The interior also contains generally and particularly to the enjoy cultural and social events. examples of certain features that event in the Australian Hall were: The building also has an could date from the original Mrs Ardler association with Australian construction and also has features J Connelly national and political history in its from each of the renovations William Cooper ownership (1920-79) by the since. -

Anti-Fascism and Italians in Australia, 1922-1945 Index Bibliography ISBN 0 7081 1158 0 1

Although Italians had migrated to Australia since the middle of the nineteenth century, it was not until the 1920s that they became aware that they were a community in a foreign land, not just isolated individuals in search of fortune. Their political, cultural, economic and recreational associations became an important factor. Many of them, although settled in Australia, still thought of themselves as an appendage of Italy, a belief strengthened by Fascism’s nationalist propaganda which urged them to reject alien cultures, customs and traditions. The xenophobic hostility shown by some Australians greatly contributed to the success of these propaganda efforts. Moreover, the issue of Fascism in Italy was a contentious one among Italians in Australia, a large minority fighting with courage and determination against Fascism’s representatives in Australia. This broad study of Italian immigrants before and during World War II covers not only the effects of Fascism, but also records the ordeal of Italian settlers in the cities and the outback during the Depression and the difficulties they faced after the outbreak of the war. It deals with a subject that has long been neglected by scholars and is an important contribution to the history of Italian migrants in Australia. Although Italians had migrated to Australia since the middle of the nineteenth century, it was not until the 1920s that they became aware that they were a community in a foreign land, not just isolated individuals in search of fortune. Their political, cultural, economic and recreational associations became an important factor. Many of them, although settled in Australia, still thought of themselves as an appendage of Italy, a belief strengthened by Fascism’s nationalist propaganda which urged them to reject alien cultures, customs and traditions. -

Gilgandra Lutheran Church

. 2 . BACK TO G I LGA ND RA" ,;� ❖--•---------·---------·-···r l OFFICIALS •=♦-Q-1 ..,__._...._...�,�--.ci_.._..-.., __.._....._._......_,.�,......�•� -,-n1111a1.1__.,4tI •5'..a-- � 'r', IN an effort to particularly I c!) have chosen to "' is the fact that ,; I' r here, naturally institution in a of which depe In prepa of research fo1 .. -;,'i . cor.siderably !, ... ,__,-�,. - - _.,.,,J. in an endeavo1 "' district• s story Secretary: Mr. C. N. Francis f·res1dent: Mr. P. P. Fallon It is but less, some err Patrons: Miss A. Curran, Mrs. E. J. Beveridge, Mrs. M. C. Garling, Messrs. securing infon carefully che A. H. N. Reichelt, G. A. Semmler, J. H. Hitchen, M. McLeod Pty. Ltd ., 0. J. McCutcheon, J. Vaughan, J. J. O'Brien, F. D. Pye, P. J. Ryan. � We of J whose mighty Hon. Treasurers: Messrs. J. J. E. Andrew and W. A. Brown. :,,. the proud mo Executive Committee: Messrs. J. Nelson, C. F. Myers, H. Collison, A. Townsend, 1 We han [ velopment, ai W. Creenaune, G. Christie, R. Diggs, Mrs. E. Townsend, Mrs. F. Varcoe, '] a1:1spici�us ,� Mrs. J. K. Alexander. f p10necrong llli times. Mode 1 greater effo Committee: Miss Travers, Miss J. Williams, Miss B. Dalmain, Miss N. Taylor. [ Mesdames H. Taylor, W. A. Brown, J. Fleming, N. J. Clements, J. Foran, � Gilgan Stanley, [ moudly ac Messrs. E. Townsend, R. F. Varcoe, W. Coomber,. J. Morris, ! . 1· E. Collison, J. Hiatt, R. Offner, B. Gould, J. Fleming, R. J. Nelson, E. Ellis, J. Curran, F. Astill, A. J. Habgood, F. Purdon, C. -

The Praying Mantis. by GILBERT WHITLEY

Table of Contents. Y o uNG SEA-EAGLE ON NEsT Frontispiece EDITORI AL 223 S o ME B IRDS OF P.&EY- Charles Bm-rett 225 SEA-DRAGONS (Phyllopteryx)- Alkm R. Jl cCullcch 231 EssAY CoMPETTTJON ... 232 A T ALK ABOUT SHEL LS- Charles H fdley . 233 THE PRAYING ni ANTJs-Gilbe'rl Wh itley . 238 CRUSTACEAN CAMOU FLEURs- F rank A . Jclfcr·:em... 243 S oME LITTLE -KNow · LIZARDs- THE G EcKo ·- .]. R. J{inghorn 247 P RIMITIVE F I RE PRODUCTION- fV illia m rr. Thorpe 249 L IFE AND S TRIFE AMON G THE ' EA EIRD&-Arthur A. Livings tone . 251 t;::j~ g> ~ ~ ~ d U1 l?=J d ~ ~ Youn~ White-breasted Sea Eagle on Nest, Capricorn Group, North Queens land. T he nest is built on a Sophor a bush, whilst In t he background is seen ~ Tournefortia a r gen1a. The leaves of this, which cluster on the ends of b ranches, a r e clad with s ilvery hairs, but th e general colour is sage green. N Su page 225. [Photo.-C. Barrl'll. Hz l?=J Published by the Australian 1ll useum College Street, Sydney. Erutor: C. ANDERSON, M.A., D.Sc. Annual Subscription, Post Free, 4/ 4, VoL. I., No. 8. APRIL, 1923. Editorial. THE AUSTRALIAN FAUNA. T the present t ime there is a good what we can to preYent, or at any rate deal of public discussion on the p ostpon~, their extinction. A rigid A subject of our native mammals ~ppli cat10n of the laws protecting wild and birds, and some of t he participants life would do much to save our mar are inclined to strike a note of pessimism supials, and the dedication of suitable as regards t he future of these mem hers of resen-es, where tho. -

Long Distance Travel in Canoes, Kayaks, Rowboats and Rafts on the Rivers of the Murray-Darling Basin from 1817 to 2012

Long Distance Travel in Canoes, Kayaks, Rowboats and Rafts on the Rivers of the Murray-Darling Basin from 1817 to 2012 by Angela BREMERS This thesis is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication (Research) of the University of Canberra June 2017 i Abstract From 1817 to 2012, paddling and rowing on the rivers of the Murray-Darling Basin played a crucial role in the region’s exploration, commerce and recreation. This thesis exposes the cultural and historical significance of journeys in human-powered craft during this period. Despite its underlying historical and cultural significance, the history of these journeys is little known and little understood. This is despite journeys by famous explorers such as Captain Charles Sturt who used rowboats on two expeditions, most notably on his 1830 expedition on the Murrumbidgee and Murray rivers. His Murray journey is well commemorated, but two earlier journeys by Surveyor-General John Oxley’s expedition are not as widely known. Those four voyages, as well as three expeditions led by Major Thomas Mitchell were instrumental in solving the mystery of the inland rivers and expanding colonial settlement (Shaw ed., 1984, pp.217, 221, 599). Following European expansion, journeys by Captain Francis Cadell and a voyage by Lieutenant-Governor of South Australia Sir Henry Edward Fox Young, determined the navigability of the Murray for paddle steamers. Until the additional linking of the railways into the basin during the 1870s and 1880s, paddle steamers provided the most efficient and reliable transport for farmers and settlers, and boosted the regional economy (Lewis, 1917, p.47; Phillips, 1972, p.50; Richmond, c.1980, p.17). -

20 DECEMBER 1999 Meeting No 1303

20 DECEMBER 1999 Meeting No 1303 MINUTES of a Meeting of the Council of the City of Sydney held in the Council Chamber at the Sydney Town Hall, commencing at 5.40pm on 20 December 1999 pursuant to Notice 19/1303 dated 16 December 1999. INDEX TO MINUTES Subject Page No. 1. Confirmation of Minutes.........................................................................................995 2. Minutes by the Lord Mayor - Museum of Contemporary Art ..............................................................................995 Monday 20 December 1999 994 Subject Page No. 3. Memorandum by the General Manager - Contributions to City Improvements Program....................................................997 4. Matters for Tabling .................................................................................................998 Reports of Committees - 5. Finance, Properties and Tenders Committee - 13 December 1999....................999 6. Cultural and City Care Committee - 13 December 1999 ..................................1002 7. Community Services, Small Business and Tourism Committee - 13 December 1999.......................................................................................................1018 8. Planning Development and Transport Committee - 13 December 1999.........1021 Reports to Council - 9. Central Sydney Local Environmental Plan 1996 - Draft Amendment No. 10 and Central Sydney Development Control Plan 1996 - Draft Amendment No. 10: Exempt and Complying Development.............................1074 10. Development Application: -

AUS'..::3.AD:AN ~QS3:Tl.I

•· ~ :-7~ \x'' V S v"' "u· '1'' -l:J \"' v AL:...:s . ·. AUS'..::3.AD:AN ~QS3:Tl.I . (AN~U..\L ltEI'OR'r OF TIIE TRUSTEES FOR TIIE YE AR ElG>:C..D 30TII JU.m:, 1938.) ·Printed under No. 17 Report from Printing Oommitteo, 16 December, 1938. To !I1s EAcr:u..t:xov Tin: G oVERNOR. 1'ilc 1\ ·,:stccs oi thu Anstr111inn Museum h c.vc the honour to submit to your Exc:-. •...:ncy thei-r eighty-fourth Ann ual R eport, beinz that i.or the yc::r cndctl 30th June, 1~;;'> . It will 1-c :;0\!u irom tl.c dct .. il:; supplied in the ~·eports i i'Ol.1 th<l variot:s sec t :ons, :.nd i.·om !'nrti..:t: ... rs of puhlic:ttions rh::t have boon issuccl dt:::-ir. r the year, thnt t}._: 1ft.S.:!uiD .. S in llrl.:viOll$ yC.l':'S };as IllllCC i opon::.~'t COLt. :out:or:s tO SCientific know J.:,:..,c, ..nu. L.., cot. im:cd to supp;y u:;eft<l iniormation to Y«:lo~.;o Dcp::; .: t:mcnt .. of Sc;.tc _:.d to the guucr_l pub:ic. 1. TRCSTEI:S • .'.. t the Dccc:nbcr Jr.cct:.:lci of the Bo::r-d, Th. F . S. :.!;.~nee w ••,. l'c-c1cct..:d to the o~.icc o:. !>rcsidc:l .. io• tnc yc.. r 19SS. T.1o Rou. Sir Chnl'lcs Tiosenth!!l, K .C.B., \'.D., :U.L.C., E:cctiYo Trustee, !'cr.i.;ncd f rom the Bo:u·u in October, 1937, consequent UI.JOn nis •nkh....