Text, Power, and Kingship in Medieval Gujarat, C. 1398-1511

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Unit 2 Foundation, Expansion and Consolidation of DELHI

UNIT 2 FOUNDATION, EXPANSION AND Trends in History Writing CONSOLIDATION OF DELHI SULTANATE* Structure 2.0 Objectives 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Conflict and Consolidation 1206-1290 2.3 The Mongol Problem 2.4 Political Consequences of the Turkish Conquest of India 2.5 Expansion under the Khaljis 2.5.1 West and Central India 2.5.2 Northwest and North India 2.5.3 Deccan and Southward Expansion 2.6 Expansion under the Tughlaqs 2.6.1 The South 2.6.2 East India 2.6.3 Northwest and North 2.7 Nature of State 2.8 Summary 2.9 Keywords 2.10 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 2.11 Suggested Readings 2.12 Instructional Video Recommendations 2.0 OBJECTIVES After going through this Unit, you should be able to: • understand the formative and most challenging period in the history of the Delhi Sultanate, • analyse the Mongol problem, • list the conflicts, nature, and basis of power of the class that ran the Sultanate, • valuate the territorial expansion of the Delhi Sultanate in the 14th century in the north, north-west and north-east, and • explain the Sultanate expansion in the south. 2.1 INTRODUCTION The tenth century witnessed a westward movement of a warlike nomadic people inhabiting the eastern corners of the Asian continent. Then came in wave upon * Dr. Iftikhar Ahmad Khan, Department of History, M.S. University, Baroda; Prof. Ravindra Kumar, School of Social Sciences, Indira Gandhi National Open University and Dr. Nilanjan Sankar, Fellow, School of Orinental and African Studies, London. The present Unit is taken from th th IGNOU Course EHI-03: India: From 8 to 15 Century, Block 4, Units 13, 14 & 15 and MHI-04: 31 Political Structures in India, Block 3, Unit 8, ‘State under the Delhi Sultanate’. -

Kirtan Leelaarth Amrutdhaara

KIRTAN LEELAARTH AMRUTDHAARA INSPIRERS Param Pujya Dharma Dhurandhar 1008 Acharya Shree Koshalendraprasadji Maharaj Ahmedabad Diocese Aksharnivasi Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Hariswaroopdasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Dharmanandandasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) PUBLISHER Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple (Kenton-Harrow) (Affiliated to Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj – Kutch) PUBLISHED 4th May 2008 (Chaitra Vad 14, Samvat 2064) Produced by: Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton Harrow All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. © Copyright 2008 Artwork designed by: SKSS Temple I.T. Centre © Copyright 2008 Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton, Harrow Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple Westfield Lane, Kenton, Harrow Middlesex, HA3 9EA, UK Tel: 020 8909 9899 Fax: 020 8909 9897 www.sksst.org [email protected] Registered Charity Number: 271034 i ii Forword Jay Shree Swaminarayan, The Swaminarayan Sampraday (faith) is supported by its four pillars; Mandir (Temple), Shastra (Holy Books), Acharya (Guru) and Santos (Holy Saints & Devotees). The growth, strength and inter- supportiveness of these four pillars are key to spreading of the Swaminarayan Faith. Lord Shree Swaminarayan has acknowledged these pillars and laid down the key responsibilities for each of the pillars. He instructed his Nand-Santos to write Shastras which helped the devotees to perform devotion (Bhakti), acquire true knowledge (Gnan), practice righteous living (Dharma) and develop non- attachment to every thing material except Supreme God, Lord Shree Swaminarayan (Vairagya). There are nine types of bhakti, of which, Lord Shree Swaminarayan has singled out Kirtan Bhakti as one of the most important and fundamental in our devotion to God. -

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

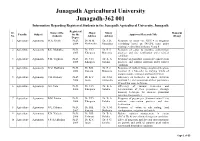

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001 Information Regarding Registered Students in the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh Registered Sr. Name of the Major Minor Remarks Faculty Subject for the Approved Research Title No. students Advisor Advisor (If any) Degree 1 Agriculture Agronomy M.A. Shekh Ph.D. Dr. M.M. Dr. J. D. Response of castor var. GCH 4 to irrigation 2004 Modhwadia Gundaliya scheduling based on IW/CPE ratio under varying levels of biofertilizers, N and P 2 Agriculture Agronomy R.K. Mathukia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. P. J. Response of castor to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Marsonia practices and zinc fertilization under rainfed condition 3 Agriculture Agronomy P.M. Vaghasia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of groundnut to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Golakia practices and sulphur nutrition under rainfed condition 4 Agriculture Agronomy N.M. Dadhania Ph.D. Dr. B.B. Dr. P. J. Response of multicut forage sorghum [Sorghum 2006 Kaneria Marsonia bicolour (L.) Moench] to varying levels of organic manure, nitrogen and bio-fertilizers 5 Agriculture Agronomy V.B. Ramani Ph.D. Dr. K.V. Dr. N.M. Efficiency of herbicides in wheat (Triticum 2006 Jadav Zalawadia aestivum L.) and assessment of their persistence through bio assay technique 6 Agriculture Agronomy G.S. Vala Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Efficiency of various herbicides and 2006 Khanpara Golakia determination of their persistence through bioassay technique for summer groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 7 Agriculture Agronomy B.M. Patolia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) to 2006 Khanpara Golakia moisture conservation practices and zinc fertilization 8 Agriculture Agronomy N.U. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q3t1s0 Author Balachandran, Jyoti Gulati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Chair This dissertation examines the processes through which a regional community of learned Muslim men – religious scholars, teachers, spiritual masters and others involved in the transmission of religious knowledge – emerged in the central plains of eastern Gujarat in the fifteenth century, a period marked by the formation and expansion of the Gujarat sultanate (c. 1407-1572). Many members of this community shared a history of migration into Gujarat from the southern Arabian Peninsula, north Africa, Iran, Central Asia and the neighboring territories of the Indian subcontinent. I analyze two key aspects related to the making of a community of ii learned Muslim men in the fifteenth century - the production of a variety of texts in Persian and Arabic by learned Muslims and the construction of tomb shrines sponsored by the sultans of Gujarat. -

Gadre 1943.Pdf

- Sri Pratapasimha Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantha-maia MEMOIR No. II. IMPORTANT INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE BARODA STATE. * Vol. I. Price Rs. 5-7-0 A. S. GADRE INTRODUCTION I have ranch pleasure in writing a short introduction to Memoir No, II in 'Sri Pratapsinh Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantharnala Series', Mr, Gadre has edited 12 of the most important epigraphs relating to this part of India some of which are now placed before the public for the first time. of its These throw much light on the history Western India and social and economic institutions, It is hoped that a volume containing the Persian inscriptions will be published shortly. ' ' Dilaram V. T, KRISHNAMACHARI, | Baroda, 5th July 1943. j Dewan. ii FOREWORD The importance of the parts of Gujarat and Kathiawad under the rule of His Highness the Gaekwad of Baroda has been recognised by antiquarians for a the of long time past. The antiquities of Dabhoi and architecture Northern the Archaeo- Gujarat have formed subjects of special monographs published by of India. The Government of Baroda did not however realise the logical Survey of until a necessity of establishing an Archaeological Department the State nearly decade ago. It is hoped that this Department, which has been conducting very useful work in all branches of archaeology, will continue to flourish under the the of enlightened rule of His Highness Maharaja Gaekwad Baroda. , There is limitless scope for the activities of the Archaeological Department in Baroda. The work of the first Gujarat Prehistoric Research Expedition in of the cold weather of 1941-42 has brought to light numerous remains stone age and man in the Vijapuf and Karhi tracts in the North and in Sankheda basin. -

South Zone Drawing Section -- Date: 10-10-2018

TO AHMEDABAD TO TO GODHARA NATIONAL HIGHWAY NO. 8 DUMAL TO AHMEDABAD TO GUJARAT FARTILIZER TO SAVLI NORTH DUMAD CHOWKDI CHHANI VEMALI SARDAR CHOK. NATIONALDENA HIGHWAY NO. 8 "A" TO GODHARA START POINT OF RUT-5 REFINERY TOWNSHIP RAMAKAKA GOLDAN CHOWKDI DEARI N A R M A D A C A N A L PRAMUKH SQ. RAJESHWAR HARMONY AMBIKA SOC. SUNDER VAN MOTNATH MAHADEV NAVRACHNA SOC. RAJESHWAR GOLD AKAS GANGA AKAS START POINT:-RUT-6 VEGETABLE & GRAIN MARKET N.T.S Trimurti KARODIYA AVANTISOC. HARANI 10 HANUMAN NARMADA KAILAS MAHADEV. TEMP. TALAV VASAHAT CHANAKYA SAMA UNDERA Abhilasha Sainik sport 24.0 M. JALARAM TEMPLE MOTIBHAI chhatralay complex E.M.E CIRCLE HIGH WAY BY PASS 100.0 M. METRO ROAD 24.0M. Transportnagar 24.0 M. 18.0 M. NAVARACHNA NANUBHAI TOWER SCHOOL 30.0 M. 12 MAHESANA Panchavati DARJIPURA ROAD 24.0 M. CIRCLE Mehsana nagar MANGAL PANDEY RD. D-CABIN SAYAJIPURA AIRPORT TOWN HALL TO AJWA Delux KANHA RESI 18.0 M. 7 MUKHI NGR.TRAN RASTA MANEKPARK AJWA O.H.TANK CROSS RD. Amitnagar Soc. KALPANA NEW V.I.P. ROAD CANTONMENT V.I.P. ROAD SOCIETY 40.0 M. GORWA 40.0 M. S.R.Petrol Pump LAXMI STUDIO NIZAMPURA HANUMAN START POINT:-RUT-1 Ghelani Petrol Pump TEMP. LAXMIPURA KHODIYARNAGAR 18.0 M. "T" "C" VUDA END POINT:-RUT-6 WARD NO:2 20.0M. BHAVAN 36.0 M. 20.0 M. 30.0 M. 14 HARANI ROAD WARD:7 OFFICE 9 Nagar Anand END POINT OF RUT-5 SANGAM END POINT:-RUT-1 C.K PRAJAPATI SCHOOL Fateganj Circle 36.0 CROSS RD. -

Asian Muslim Women in General

Introduction Huma Ahmed-Ghosh Muslim women’s lives in Asia traverse a terrain of experiences that defy the homogenization of “the Muslim woman.” The articles in this volume reveal the diverse lived experiences of Muslim women in Islamic states as well as in states with substantial Muslim populations in Asia and the North American diaspora.1 The contributions2 reflect upon the plurality of Mus- lim women’s experiences and realities and the complexity of their agency. Muslim women attain selfhood in individual and collective terms, at times through resistance and at other times through conformity. While women are found to resist multilevel patriarchies such as the State, the family, local feudal relations, and global institutions, they also accept some social norms and expectations about their place in society because of their beliefs and faith. Together, this results in women’s experience being shaped by particular structural constraints within different societies that frame their often limited options. One also has to be aware of academic rhetoric on “equality” or at least women’s rights in Islam and in the Quran and the reality of women’s lived experience. In bringing the diverse experiences of Asian women to light, I hope this book will be of social and political value to people who are increasingly curious, particularly post 9/11,3 about Islam and the lives of Muslim women globally. Authors in this collection locate their analysis in the intersectionality of numerous identities. While the focus in each contribution is on Muslim women, they are Muslim in a way framed by their specific context that includes class and ethnicity, and local positionality that is impacted by inter- national and national interests and by the specificities of their geographic locations. -

Dalpat S Rajpurohit

DALPAT S RAJPUROHIT Department of Asian Studies, WCH 4.104B University of Texas at Austin 120 Inner Campus Dr Stop G9300 Austin, TX 78712-1251 Email: [email protected] Office: 512-471-1219 PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor (tenure-track), University of Texas at Austin, Fall 2019 – present. Instructor, University of Texas at Austin, Fall 2018 – Spring 2019. Lecturer, Hindi-Urdu: Columbia University, New York (July 2008 to June 2018). Hindi Instructor: American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS), New Delhi and Jaipur, India (May 2007 - March 2008). Hindi Instructor, Presidency University, Kolkata, Fall 2014. Hindi instructor: Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, Spring 2006. EDUCATION Ph.D. Presidency University, Kolkata, 2019 M.Phil. Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 2008 M.A. Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 2005 B.A. Jai Narayan Vyas University, Jodhpur, 2002 JOURNAL ARTICLES (forthcoming) “Bhakti versus Rīti? The Sants’ Perspective” in the Bulletin of the School of Oriental & African Studies. 2019 “Vaishnava Models for Nirgun Devotion” in the Journal of Vaishnava Studies. Vol.28, No.1 Fall 2019, 157-171 2017 Santkavi Sundardās aur 17vīṅ Sadī ke Sattā Pratiṣṭhān (Poet-Saint Sundardas and the 17th Century Elite Institutions), in Sammelan Patrikā [a quarterly peer-reviewed journal of Hindi literature], Hindi Sāhitya Sammelan, Allahabad, April-June 2017, 67-76. 2016 Bhakti kā Kāvyaśāstra: Dādūpanthī Sundardās kā Rītikāvya se Samvād (The poetics of Bhakti: Dādūpanthī Sundardās’s Dialogue with Courtly Hindi Poetry) in Śodh- Hastakśep [a bi-annual journal of Hindi literature published from Varanasi], Vol.6, No.12, July- December 1-10. 2008 Madhyakālīn Santbānī Sanklan kī "Sarvaṅgī" Paramparā aur Bhakti Samvedanā (The "Sarvangī" Anthology Tradition of Early Modern India and Bhakti Sensibility) in Ālocanā (special issue on Bhakti-Kāl) [a quarterly journal in Hindi published from Patna], Chief editor Namwar Singh, 45-54. -

Ethnographic Series, Part-V-B, Vol-XIII, Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 Y·OLUMB xm. PART V-B PUNJAB (ETHNOGRAPIlIC ~ERIE's) (BATWAL; BHAN.JRA; DU.VINAJ MAHA,SHA OR DOOM; ~AGRA; qANDHILA OR GANnIL GONDOLA; ~ARERA; DEHA, DHAYA OR DHEA). P.;L. SONDHI.. DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS AND EX O:FFICTO SUPERINTENDENT OF CENSUS OPERAT~ONS, PUNJAB. SUMMARY 01' CONTENTS Pages Foreword v Preface vii-x 1. Batwal 1-13 II. Bhanjra 19-29 Ill. Dumna, Mahasha or Doom 35-49 IV. Gagra 55-61 V. GandhUa or GandH Gondo1a 67-77 VI. Sarera 83-93 VII. Deha, Dhaya or Dhea .. 99-109 ANNEXURE: Framework for ethnographic study .. 111-115 }1~OREWORD The Indian Census has had the privIlege of presenting authentic ethnographic accounts of Indian communities. It was usual in all censuses to collect and publish information on race, tribes and castes. The Constitution lays down that "the state shall promote with special care educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people and, in parti cular, of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation". To assist states in fulfiHing their responsibility in this regard the 1961 Census provided a series of special tabulations of the social and economic data on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are notified by the Presi· dent under the Constitution and the Parliament is empowered to include or exclude from the lists any caste or tribe. No other source can claim the same authenticity and comprehensiveness as the census of India to help the Government in taking de· cisions on matters such as these. -

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century Thesis submitted for the dc^ee fif DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY By AJAZ BANG Under the supervision of PROF. IQTIDAR ALAM KHAN Department of History Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarb- 1983 T388S 3 0 JAH 1392 ?'0A/ CHE':l!r,D-2002 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY TELEPHONE SS46 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that the thesis entitled 'Soci•-Political Condition Ml VB Wtmmimt of Gujarat / during the fifteenth Century' is an original research work carried out by Aijaz Bano under my Supervision, I permit its submission for the award of the Degree of the Doctor of Philosophy.. /-'/'-ji^'-^- (Proi . Jrqiaao;r: Al«fAXamn Khan) tc ?;- . '^^•^\ Contents Chapters Page No. I Introduction 1-13 II The Population of Gujarat Dxiring the Sixteenth Century 14 - 22 III Gujarat's External Trade 1407-1572 23 - 46 IV The Trading Cotnmxinities and their Role in the Sultanate of Gujarat 47 - 75 V The Zamindars in the Sultanate of Gujarat, 1407-1572 76 - 91 VI Composition of the Nobility Under the Sultans of Gujarat 92 - 111 VII Institutional Featvires of the Gujarati Nobility 112 - 134 VIII Conclusion 135 - 140 IX Appendix 141 - 225 X Bibliography 226 - 238 The abljreviations used in the foot notes are f ollov.'ing;- Ain Ain-i-Akbarl JiFiG Arabic History of Gujarat ARIE Annual Reports of Indian Epigraphy SIAPS Epiqraphia Indica •r'g-acic and Persian Supplement EIM Epigraphia Indo i^oslemica FS Futuh-^ffi^Salatin lESHR The Indian Economy and Social History Review JRAS Journal of Asiatic Society ot Bengal MA Mi'rat-i-Ahmadi MS Mirat~i-Sikandari hlRG Merchants and Rulers in Giijarat MF Microfilm.