How We Gather (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal Articles and Conference Presentations

Conference Bibliography – LENA User Presentations The following research was presented by LENA users at major conferences. Click here for research presented at LENA Conferences. 2017 Gilkerson, J., & Richards, J. A. (2017, September). Early childhood language environments predict outcomes in adolescence: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study using automated analysis. Poster session presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference & Exhibition, Chicago, IL. Yoo, H., Ramsay, G., Bene, E. R., Long, H., van Mersbergen, M., Buder, E. H., . Oller, D. K. (2017, November). Volubility of infant distress vocalizations across the first year of life. Seminar conducted at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention, Los Angeles, CA. 2016 Yoo, H., & Oller, D. K. (2016, November). Temporal structure of turn-taking in parent-infant dyads: A naturalistic study with 0-3-month-olds. Poster session presented at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention, Philadelphia, PA. 2015 Walle, E. A., & Warlaumont, A. S. (2015, July). Infant locomotion, the language environment, and language development: A home observation study. Paper presented at the 37th Annual Conference of Cognitive Science Society, Pasadena, CA. Yoo, H., Buder, E. H., Lee, C. C., & Oller, D. K. (2015, November). Temporal structure of parent vocal responsiveness to infant cry and protophones. Seminar conducted at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention, Denver, CO. 2014 Ganek, H., & Eriks-Brophy, A. (2014, June). Using the Language ENvironment Analysis (LENA) System to study language socialization practices. Poster session presented at the Symposium on Research in Child Language Disorders, Madison, WI. Lee, J., Ali, H., Ziaei, A., & Hansen, J. H. (2014, October). -

Leigh Adair Kale

Leigh Kale D’Amico Research Assistant Professor College of Education University of South Carolina 803-777-8072 [email protected] Education Doctor of Education in Curriculum and Instruction, 2007 University of South Carolina-Columbia Dissertation Topic: Impact of Accountability on K-2 Teaching Practices Master of Public Administration, 1999 University of North Carolina at Charlotte Focus Areas: Education Policy and Administration Bachelor of Arts in English and Communication Studies, 1996 University of North Carolina at Greensboro Experience May 2006 to Research Assistant Professor (July 2010 to Present) Present Research Associate (August 2007 to July 2010) Research Assistant (May to August 2006, November 2006 to May 2007) Research, Evaluation, and Measurement Center, College of Education University of South Carolina-Columbia • Served as principal or co-principal investigator/evaluator on projects totaling approximately $2.8 million since July 1, 2010 • Serve as principal evaluator or consultant on evaluations related to early childhood education funded by South Carolina Education Oversight Committee, South Carolina State Library, South Carolina Department of Social Services, South Carolina First Steps, United Way, and Mary Black Foundation • Serve as principal evaluator on School Improvement Grant (SIG) project and educator evaluation project funded by US and SC Departments of Education • Serve as principal evaluator on National Science Foundation projects to prepare STEM secondary teachers and enhance teacher leadership of current -

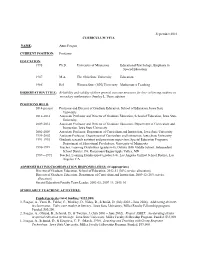

Foegen CV 9 18 Website

September 2018 CURRICULUM VITA NAME: Anne Foegen CURRENT POSITION: Professor EDUCATION: 1995 Ph.D. University of Minnesota Educational Psychology, Emphasis in Special Education 1987 M.A. The Ohio State University Education 1986 B.S. Winona State (MN) University Mathematics Teaching DISSERTATION TITLE: Reliability and validity of three general outcome measures for low- achieving students in secondary mathematics; Stanley L. Deno, advisor POSITIONS HELD: 2014-present Professor and Director of Graduate Education, School of Education, Iowa State University 2012-2014 Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Education, School of Education, Iowa State University 2009-2012 Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Education, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Iowa State University 2002-2009 Associate Professor, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Iowa State University 1995-2002 Assistant Professor, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Iowa State University 1991-1995 Graduate research assistant and practicum supervisor, Special Education Programs, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Minnesota 1990-1991 Teacher, Learning Disabilities (grades 6-8), Dakota Hills Middle School, Independent School District 196, Rosemount/Eagan/Apple Valley, MN 1987—1991 Teacher, Learning Handicapped (grades 6-8), Los Angeles Unified School District, Los Angeles, CA ADMINISTRATIVE/COORDINATION RESPONBILITIES: (if appropriate) Director of Graduate Education, School of Education, 2012-13 (30% service allocation) Director of Graduate Education, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, 2009-12 (20% service allocation) Special Education Faculty Team Leader, 2003-05; 2007-11; 2015-16 SCHOLARLY TEACHING ACTIVITIES: Funded projects (total funding: $122,200) 3. Foegen, A., Vann, R., Fuhler, C., Merkley, D., Niday, D., Schmidt, D. (July 2003 – June 2004). Addressing diversity in classrooms: Video case studies in literacy. -

Auburn Seniors Auburn Residents to Celebrate at Participate in Boston Sheriff’S Senior Picnic Marathon® Jimmy Fund Walk

www.StonebridgePress.com Friday, September 6, 2019 Newsstand: 75 cents Auburn seniors Auburn residents to celebrate at participate in Boston Sheriff’s Senior Picnic Marathon® Jimmy Fund Walk AUBURN — Six residents There is a distance option from Auburn will walk one for everyone. Participants of the four designated dis- can choose from any of tances along the historic the below four distanc- Boston Marathon® course es along the historic Boston this September in the Boston Marathoncourse: Marathon® Jimmy - 5K Walk (3.1 miles) from Fund Walk presented by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Hyundai, which raises the starting at 1:45 p.m. most money of any single day - 10K Walk (6.2 miles) from walk in the country. Newton; rolling start from 10 a.m. to Noon Laura Rogan, Jessica - Half Marathon Walk (13.1 Hickson, Toni Whitcher, miles) from Wellesley; rolling Thomas Turco, Michael Cotter start from 8:30 to 10:30 a.m. and Brian O’Connor will join - Marathon Walk (26.2 9,000 expected participants in miles) from Hopkinton; rolling the annual event, which takes start from 5:30 to 7:30 a.m. place Sunday, September 22, Walkers are treated to 12 2019. Money raised from the refueling stations along the Jimmy Fund Walk will sup- course, as well as poster-sized port adult and pediatric patient photographs of inspiring Walk care and cancer research at Heroes at each mile and half the nation’s premier cancer mile marker. center, Dana-Farber Cancer Courtesy Photo Institute. The event has raised All distance options con- Sheriff Lew Evangelidis pictured with Auburn seniors as they enjoy the festivities at the Sheriff’s more than $135 million over clude at the Copley Square Annual Senior Picnic held on Aug. -

Dukecv 10.29.19

N. K. Duke, p. 1 of 89 VITA Nell K. Duke October 29, 2019 University of Michigan School of Education, Room 4109 610 East University Avenue Ann Arbor, MI 48109 phone: (734) 615-0586 fax: (734) 936-1606 email: [email protected] website: http://umich.edu/~nkduke/ EDUCATIONAL HISTORY: Harvard Graduate School of Education Ed.D. 1999 Department of Human Development and Psychology Ed.M 1995 Program in Language and Literacy Swarthmore College B.A. 1993 Special Major in Linguistics Cognates in Psychology and Education Concentration in Black Studies Certification Program in Elementary Education Eastern College -- 1992 Courses in Reading and Language Arts SELECTED POSITIONS: Professor, Literacy, Language, and Culture, Department of Educational 2012 – present Studies; Professor, Combined Program in Education and Psychology, University of Michigan School of Education Professor, Teacher Education and Educational Psychology, Michigan State 2009 – 2013 University College of Education (on leave 2012 – 2013) Co-Director, Literacy Achievement Research Center (LARC) 2006 – 2012 Co-Founder and Associate Director, Literacy Achievement Research Center 2004 – 2006 (LARC) Associate Professor, Michigan State University College of Education 2003 – 2009 Assistant Professor, Michigan State University College of Education 1998 – 2003 N. K. Duke, p. 2 of 89 SELECTED AWARDS: Maryann Manning Literacy Scholar Award, University of Alabama, 2019 Birmingham William S. Gray Citation of Merit, International Literacy Association 2018 Michigan Association of Intermediate School -

AUBURN ARRESTS Obtained Through Either Press Phone Calls, 10 White Terrace

(508) 943-4800 Newsstand: 75 cents www.auburnnews.net Saturday, March 30, 2013 THIS WEEK’S Auburn News QUOTE “When the heart moving to Fridays! speaks, the mind AUBURN — The Auburn News, your source for week- finds it indecent ly, local news, is moving to object.” from Saturday publication to Fridays, starting with Milan Kundera next week’s edition on Friday, April 5. All of our deadlines concerning calen- dar entries, obituaries, advertising, letters to the INSIDE editor and all other submis- sions remain unchanged. The only thing changing is CALENDAR ..............B1 the day of delivery! If you have any questions, do not OPINION ................A6 hesitate to call Editor Adam SENIORS ................A8 Minor, at 508-909-4130, or e- mail aminor@stonebridge- OBITUARIES ............A9 press.com. See you in your SPORTS................A10 mailbox next Friday! Thanks for reading the Gus Steeves photo Auburn News! LOCAL Michael Errickson, of Diversified Technology Consultants, talks about some of the changes involved in the Bay Path renovation project. A hopping good time Bay Path commences planning hearing ROJECT AIMS TO START THIS SUMMER Boys Date Night P Page A3 BY GUS STEEVES and where water flows off the hill. STONEBRIDGE PRESS STAFF WRITER Architect David McKinley of Kaestle-Boos CHARLTON — Bay Path Regional Associates is hoping the process is quick. SPORTS Vocational Technical High School’s $73 mil- “We’d like to go out for an early bid pack- lion renovation and expansion project kicked age if we can, to make use of the summer,”he off it’s public hearing Wednesday, March 20, said, referring to the fact the school wants to before the Planning Board. -

What Is Your Story? Page 15 T November Project Page 27

Publication of the Richmond Road Runners Club November/December 2017 | Volume 40, Issue 6 What is your story? page 15 t November Project page 27 Miles and Minutes is the official newsletter for and by members of the Richmond Road Runners Club (RRRC). [ EDITOR’S LETTER ] The RRRC is a nonprofit organization whose goal is to foster fitness and a healthy lifestyle through running in the metro Richmond, Virginia area. The club We have those races, or experiences is affiliated with the Road Runners Club of America and sponsors nearly 20 races throughout the year with distances with other runners, that stick with ranging from 1 mile to 50K. As a service to the community, the club contracts us. We remember them years, maybe to provide race services. These services range from renting equipment to full- computerized race timing. The club provides services for over 30 events during even decades later. We remember the year. Club Officers the faces we see, the strangers who Bill Kelly President Jim Oddono Vice President/Operations helped us through our rough patch, Ed Kelleher Vice President/Communications Rosie Schutte Secretary or the time we made sure the runner Ralph Gibbs Treasurer who collapsed on the course got the Function Heads Mara George Membership Director help they needed. Glenn Melton Equipment Manager Jim Oddono Race Coordinator Don Garber Club Historian Maybe we wake up early to spend Group Runs Technology, Web time helping a friend with their speed workout. Fartleking Rosie Schutte, Ralph Gibbs Grand Prix Coordinators is better when you have someone you trust egging you on. -

Kinaesthetic Cities: Studying the Worlds of Amateur Sports and Fitness in Contemporary Urban Environments

Kinaesthetic Cities: Studying the worlds of amateur sports and fitness in contemporary urban environments Alan Latham and Jack Layton Department of Geography, University College London [email protected], [email protected] Final edits May 2019 Abstract Developing the concept of kinaesthetics this article undertakes a critical re-description of amateur sports and fitness to explore the topographies, materials, innovation, and socialities that make up urban environments. Extending work on affect and urban materiality within geography and elsewhere, we argue that amateur sport and fitness animates many cities in ways that are frequently overlooked. The paper aims to 1) broaden understandings of amateur sport and fitness practices; 2) reframe perspectives on the kinds of environments cities are; 3) develop a prospective politics of provision involving the design and maintenance of a social infrastructure of amateur sport and fitness. Key Words: Urban, materiality, sociality, sport, exercise, infrastructure, environment, affect, publics. Page 1 i. Introduction Cities are full of people engaged in all sorts of physical fitness and sporting activity. People climbing, running, cycling, swimming, dancing, playing, training, jumping, crawling, skating, balancing, skipping, racing, diving, fighting, wrestling, walking. These are everyday activities that enliven and remake urban environments. And it is the very affordances found and provided in cities that enable many of these practices to take hold and proliferate. There is evidence from across a range of disciplines that suggests these kinds of activities can help to fight against chronic diseases (Booth, et al. 2012), mental health problems (Deslandes, 2014), loneliness (Pels and Kleinert, 2016) and even increase life expectancy (Lee, et al. -

Maria E. Reyes-Macpherson

CURRICULUM VITAE MARIA E. REYES-MACPHERSON Home Address Office Address 13179 Liberty Square Dr. University of Central Florida Orlando, FL 32828 Department of Child, Family, & Community Sciences (407) 658-4086 College of Education Post Office Box 161250 Orlando, FL 32816-1250 (407) 823-5445 E-mail: [email protected] ACADEMIC BACKGROUND Ph.D. UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA, Gainesville, FL 1996 Major: Special Education (Learning Disabilities) Minor: Bilingual-Multicultural Education M.Ed. FORDHAM UNIVERSITY, Lincoln Center, NY 1983 Major: Special Education (Learning Disabilities) B.S. UNIVERSITY OF PUERTO RICO, Mayagüez, PR 1978 Major: Psychology Minor: Education PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Universities/Colleges 1997-present Associate Professor, Department of Child, Family, & Community Sciences, College of Education University of Central Florida, Orlando, Florida 1994 –1997 Research Specialist, Latino Families Research Project Department of Special Education, College of Education University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 1996 –1997 Instructor Child Development Program Santa Fe Community College, Gainesville, Florida 1993-1996 Graduate Assistant/Undergraduate Teaching & Intern Supervision Special Education & Unified Program, College of Education, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida María E. Reyes-Blanes Curriculum Vitae Page 2 K-12 Schools 1992-1993 Pre-school teacher, private learning center Gainesville, Florida 1991 –1992 Educational Therapist & Resource Teacher, Colegio Maristas Guaynabo, Puerto Rico 1985 –1991 Director, Abilties Bound -

VITA DANIEL BERNARD CRIMMINS, PH.D. Director of Psychology, Westchester Institute for Human Development, Valhalla

VITA DANIEL BERNARD CRIMMINS, PH.D. OFFICE ADDRESS Center for Leadership in Disability University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities School of Public Health Georgia State University Suite 514 75 Piedmont Ave. Atlanta, GA 30303 404.413.1286 (office) / 404.293.3588 (cell) [email protected] (e-mail) HOME ADDRESS 763 Amsterdam Ave. Atlanta, GA 30306 404.600.3690 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE (Full Time) 2008 - Present Director, Center for Leadership in Disability, University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDD), Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 2011 - Present Director, Georgia Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities (GaLEND) Program, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 2011 - Present Clinical Professor, School of Public Health, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 2009 - 2011 Clinical Professor, Institute of Public Health and College of Health and Human Sciences, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 2008 - 2009 Visiting Professor, Institute of Public Health, College of Health and Human Sciences, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 2008 Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 2008 Director, Marcus Institute UCEDD, Atlanta, GA 2007 Associate Director, Marcus Institute UCEDD, Atlanta, GA 2005 - 2007 Vice President for Community Programs, Westchester Institute for Human Development, Valhalla, NY 2002 - 2003 Robert Wood Johnson Health Policy Fellow, Institute of Medicine (9/02-12/02) and Staff of U.S. Senator James M. Jeffords -

Martha E. Castañeda

Martha E. Castañeda Miami University Department of Teacher Education 401 McGuffey Hall Oxford, OH 45056 [email protected] 513.529.7280 EDUCATION Ph.D. 2005 Second Language Acquisition and Instructional Technology University of South Florida Tampa, FL Dissertation: Corrective Feedback in Online Asynchronous and Synchronous Environments in Spanish as a Foreign Language Classes Comprehensive areas: Foreign Language Education, English for Speakers of Other Languages, and Technology in Language Learning, Teacher Preparation, Applied Linguistics M.A. 1997 Spanish Linguistics University of Florida Gainesville, FL Minor: Portuguese B.A. 1994 Major: Spanish Minor: English University of North Florida Jacksonville, FL A.A. 1992 General Education Manatee Community College Bradenton, FL PRESENT APPOINTMENT 2007-present Assistant Professor of Foreign Language Education/ESOL Miami University School of Education, Health, and Society PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2005-2007 Assistant Professor of Spanish DePaul University Modern Language Department 2001-2005 Program Assistant University of South Florida Second Language Acquisition and Instructional Technology Ph.D. Program 2004-2005 Internship Supervisor University of South Florida Department of Foreign Language Education 1995-2005 Graduate Teaching Assistant University of South Florida Department of Foreign Language Education and World Language Education 2002-2005 Grant Program Manager University of South Florida Project Manager of the Support for Elementary Educators through Distance Education in Spanish (SEEDS) Title VI Federal Grant project 2003-2004 ITA Graduate Assistant University of South Florida International Teaching Assistants Workshop 1994-2004 Faculty Consultant University of South Florida Educational Testing Services (ETS) 1997-1999 Visiting Instructor University of Central Florida 1995-1997 Graduate Teaching Assistant University of Florida 1994-1995 Spanish Teacher Andrew Jackson High School BOOKS Erben, T., Ban, R., & Castañeda, M. -

CV Carey April 16 2021

Michael P. Carey, Ph.D. Revised: September 16, 2021 Page 1 MICHAEL P. CAREY, PH.D. CURRICULUM VITAE CURRENT POSITIONS Senior Research Scientist, Center for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, The Miriam Hospital Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior (Medicine), Brown University Professor of Behavioral and Social Sciences (Public Health), Brown University Co-Director, T32 Postdoctoral Program in Child/Adolescent Biobehavioral HIV Research CONTACT INFORMATION Mail: Center for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine; The Miriam Hospital Coro West, Suite 309; 164 Summit Avenue; Providence, RI 02906 Phone: 401-793-8218 Fax: 401-793-8059 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION 1978 Exchange Student, Austro-American Institute, Vienna, Austria 1980 B. S., Psychology, St. Lawrence University 1984 M. A., Clinical Psychology, Vanderbilt University 1985-1986 Internship in Clinical Health Psychology, Brown University 1986 Ph.D., Clinical Psychology, Vanderbilt University POSTGRADUATE COURSEWORK 1990 Department of Psychology, Ohio State University 1993 School of Public Health, University of Michigan 1993, 1994 School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University HONORS AND AWARDS 1976 Edith Craig Grace Reynolds Scholarship, William K. Wieber Memorial Scholarship, New York State Regents Scholarship, St. Lawrence University Trustee Scholarship 1979 Omicron Delta Kappa (Honorary Society for Leadership) 1980 J. H. L. Roach Outstanding Psychology Graduate, St. Lawrence University J. P. Guilford (American Psychological Association) Undergraduate Research Award,