Reinterpreting Malevich: Biography, Autobiography, Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Museum of Pictorial Culture

The Museum Of Pictorial Culture From Less-Known Russian Avant-garde series Lev Manovich and Julian Sunley, 2021 Although we usually assume think that first museum of The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, 2019-2020, curated by Dr. modern art was MoMA (New York, 1929), an earlier museum Liubov Pchelkina. From the exhibition description: called Museum of Pictorial Culture was established in 1919 “2019 will mark 100 years since the implementation of the and run by most important Russian avant-garde artists until unique museum project of Soviet Russia – the creation of the its closing in 1929. Our essays discuss innovative museum Museum of Pictorial Culture, the first museum of contemporary concepts developed by these artists, and point out their art in our country… “The exhibition will present the history of the Museum of Pictorial Culture as an important stage in the history relevance to recent museum experiments in presenting their of Russian avant-garde and the history of the Tretyakov Gallery’s collections online using visualization methods. acquisitions. The exposition will reflect the unique structure of the museum. The exhibition will include more than 300 You can find our sources (including for images) and further paintings, drawings, sculptures from 18 Russian and 5 foreign reading at the bottom of the essay. The main source for this collections. For the first time, the audience will be presented essay is the the exhibition 'Museum of Pictorial Culture. To the with experimental analytical work of the museum. Unique 100th Anniversary of the First Museum of Contemporary Art’ at archival documents will be an important part of the exposition.” Room C at the original Museum of Pictorial Culture, containing works by Room C reconstructed at The Tretyakov Gallery, 2019. -

Download: Brill.Com/Brill-Typeface

Poets of Hope and Despair Russian History and Culture Editors-in-Chief Jeffrey P. Brooks (The Johns Hopkins University) Christina Lodder (University of Kent) Volume 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/rhc Poets of Hope and Despair The Russian Symbolists in War and Revolution, 1914-1918 Second Revised Edition By Ben Hellman This title is published in Open Access with the support of the University of Helsinki Library. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Angel with sword, from the cover of Voina v russkoi poezii (1915, War in Russian Poetry). Artist: Nikolai K. Kalmakov (1873-1955). Brill has made all reasonable efforts to trace all rights holders to any copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful the publisher welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission matters. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

INSTRUMENTS for NEW MUSIC Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

SOUND, TECHNOLOGY, AND MODERNISM TECHNOLOGY, SOUND, THOMAS PATTESON THOMAS FOR NEW MUSIC NEW FOR INSTRUMENTS INSTRUMENTS PATTESON | INSTRUMENTS FOR NEW MUSIC Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserv- ing and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribu- tion to this book provided by the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The publisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Curtis Institute of Music, which is committed to supporting its faculty in pursuit of scholarship. Instruments for New Music Instruments for New Music Sound, Technology, and Modernism Thomas Patteson UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distin- guished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activi- ties are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institu- tions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2016 by Thomas Patteson This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY- NC-SA license. To view a copy of the license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. B. Poplavsky, Stat’i. Dnevniki. Pis’ma (Moscow: Knizhnitsa, 2009), p. 126. 2. I address here in the first instance the problem of relatively limited aware- ness beyond the Russian-speaking world of russophone literary production of the Parisian diaspora. At the same time, there were spectacular cases of success in the West of those émigrés who did participate in the intellectual life of their host country by publishing in French (L. Livak, Russian Emigrés in the Intellectual and Literary Life of Interwar France: A Bibliographical Essay (Montreal: McGill Queen’s University Press, 2010)). 3. Bunin was the first Russian writer to receive this distinction (there have been five Russian laureates to date). Perhaps to an even greater extent than today, the decision of the Nobel committee was dictated by political considerations—Bunin’s chief opponent was the Soviet candidate, Maxim Gorky. Despite the obvious prestige and an increase in book sales and trans- lation contracts, as well as a boost in self-esteem for Russian émigré writers, Bunin’s Nobel Prize provided few long-term benefits for the literary diaspora (I. Belobrovtseva, “Nobelevskaia premiia v vospriiatii I.A. Bunina i ego bliz- kikh,” Russkaia literatura 4 (2007): 158–69; T. Marchenko, “En ma qualité d’ancien lauréat... Ivan Bunin posle Nobelevskoi premii,” Vestnik istorii, literatury, iskusstva, 3 (2006), 80–91). 4. This formula was used by Varshavsky in his 1930s articles and in a later book, in which he paid tribute to his generation and documented its activities: V. Varshavsky, Nezamechennoe pokolenie (New York: izd-vo Chekhova, 1956). -

Catalogue Reviews

Catalogue Reviews THE COSMOS OF THE RUSSIAN EL COSMOS DE LA VANGUARDIA RUSA AVANT-GARDE$UWDQG6SDFH([SORUDWLRQ Arte y Exploración Espacial 1900-1930 John E. Bowlt, Nicoletta Misler, Maria Tsantsanoglou, Editors John E. Bowlt, Nicoletta Misler, Maria Tsantsanoglou, Editors State Museum of Contemporary Art Costakis Collection, Fundación Botin, Santander, Spain 30€ Thessaloniki £30.65 / 35€ / $48.32 370 pp 117 col plates 108 in-text illus 68 264 pp. Many colour illus Bilingual Greek and English edition Articles in English translation ISBN 978 960 9409 11 7 ISBN 978-84-96655-59-0 “In the 1910s and 1920s the popular press ran countless backdrops for Victory Over the Sun of 1913. (See P. Railing and DUWLFOHV RQ VSDFH VSDFH ÀLJKW H[WUDWHUUHVWULDO OLIH SK\VLFDO C. Wallis, “Journey in Space-Time in the Vehicle of Destiny” trajectories, eclipses and so on, stimulated, no doubt, by the in A. Kruchenykh, Victory Over the Sun. Translated by Evgeny LQWHUPLWWHQWWULXPSKVRIWKH¿UVW5XVVLDQDLUSODQHEXLOGHUVSLORWV Steiner, Editor, P. Railing. Artists.Bookworks, 2009.) Artists and aerodynamicists”, write the curators of this exhibition, such as Ivan Kudriashev represented comets, but none of John E. Bowlt, Nicoletta Misler and Maria Tsantsanoglou. Rodchenko’s comet paintings are included in the exhibitions. 7KDW D FRQVHTXHQW IDVFLQDWLRQ ZLWK WKH KLJK IURQWLHU ¿UHG WKH Then there are imaginations of vehicles for space travel such LPDJLQDWLRQVRI5XVVLDQ$YDQW*DUGHDUWLVWVLVFRQ¿UPHGE\WKH as those by Georgii Kritikov, or of space cities by Klutsis in his diverse exhibits selected for these two exhibitions. series of the Dynamic City, later renamed Project for a City of 'LUHFWO\ UHODWHG WR ÀLJKW DUH ZRUNV VXFK DV 9ODGLPLU the Future. -

1. Coversheet Thesis

Eleanor Rees The Kino-Khudozhnik and the Material Environment in Early Russian and Soviet Fiction Cinema, c. 1907-1930. January 2020 Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Slavonic and East European Studies University College London Supervisors: Dr. Rachel Morley and Dr. Philip Cavendish !1 I, Eleanor Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Word Count: 94,990 (including footnotes and references, but excluding contents, abstract, impact statement, acknowledgements, filmography and bibliography). ELEANOR REES 2 Contents Abstract 5 Impact Statement 6 Acknowledgments 8 Note on Transliteration and Translation 10 List of Illustrations 11 Introduction 17 I. Aims II. Literature Review III. Approach and Scope IV. Thesis Structure Chapter One: Early Russian and Soviet Kino-khudozhniki: 35 Professional Backgrounds and Working Practices I. The Artistic Training and Pre-cinema Affiliations of Kino-khudozhniki II. Kino-khudozhniki and the Russian and Soviet Studio System III. Collaborative Relationships IV. Roles and Responsibilities Chapter Two: The Rural Environment 74 I. Authenticity, the Russian Landscape and the Search for a Native Cinema II. Ethnographic and Psychological Realism III. Transforming the Rural Environment: The Enchantment of Infrastructure and Technology in Early-Soviet Fiction Films IV. Conclusion Chapter Three: The Domestic Interior 114 I. The House as Entrapment: The Domestic Interiors of Boris Mikhin and Evgenii Bauer II. The House as Ornament: Excess and Visual Expressivity III. The House as Shelter: Representations of Material and Psychological Comfort in 1920s Soviet Cinema IV. -

Russians Abroad-Gotovo.Indd

Russians abRoad Literary and Cultural Politics of diaspora (1919-1939) The Real Twentieth Century Series Editor – Thomas Seifrid (University of Southern California) Russians abRoad Literary and Cultural Politics of diaspora (1919-1939) GReta n. sLobin edited by Katerina Clark, nancy Condee, dan slobin, and Mark slobin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: The bibliographic data for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-214-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-61811-215-6 (electronic) Cover illustration by A. Remizov from "Teatr," Center for Russian Culture, Amherst College. Cover design by Ivan Grave. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Table of Contents Foreword by Galin Tihanov ....................................... -

Download Information on the Artist and the Artwork

www.points-of-resistance.org LUTZ BECKER AFTER THE WALL (1999/2014), Sound Sculpture on loop, 37 min 18 sec, composed of 5 parts: § Potsdamer Platz: Strong atmosphere. It is the basis of the installation. Hammering and distant voices. § Invalidenstrasse: Dramatic close-up percussion of hammers. § Checkpoint Charlie: Heavy percussion. Massive rhythmical sound bundles. § Brandanburger Tor: Relaxed, regular beats quite close. § Night: End piece with dominant echos. The Berlin Wall was first breached on 9th November 1989, as the result of popular mass meetings and demonstrations within the GDR. It was not demolished at a single stroke, but over days and weeks was slowly chipped away as people from East and West joined together to obliterate a hated symbol of oppression. This was the first in a chain of events that led to the end of the Soviet Union and the Iron Curtain. Europe was freer than it had ever been before! And the ramifications spread the world-over! In 1989 the whole of Berlin rang and rocked to the liberating sound of hammers and pickaxes as the Wall was demolished. It was intended to build a better world without any walls. Artist and film-maker Lutz Becker made a montage of these percussive sounds as the opening work in After the Wall, a large exhibition of art from the post-communist countries of Europe, that opened in 1999 on the 10th anniversary of this world-changing event. Now for Points of Resistance, at Berlin’s iconic point of resistance in the Zionskirch, we encourage you to scan the barcode and listen on your phones -

Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Koenig Books Isbn 978-3-86560-706-5 Early 20Th Century Russia · Andrey Smirnov

SOUND IN Z Russia, 1917 — a time of complex political upheaval that resulted in the demise of the Russian monarchy and seemingly offered great prospects for a new dawn of art and science. Inspired by revolutionary ideas, artists and enthusiasts developed innumerable musical and audio inventions, instruments and ideas often long ahead of their time – a culture that was to be SOUND IN Z cut off in its prime as it collided with the totalitarian state of the 1930s. Smirnov’s account of the period offers an engaging introduction to some of the key figures and their work, including Arseny Avraamov’s open-air performance of 1922 featuring the Caspian flotilla, artillery guns, hydroplanes and all the town’s factory sirens; Solomon Nikritin’s Projection Theatre; Alexei Gastev, the polymath who coined the term ‘bio-mechanics’; pioneering film maker Dziga Vertov, director of the Laboratory of Hearing and the Symphony of Noises; and Vladimir Popov, ANDREY SMIRNO the pioneer of Noise and inventor of Sound Machines. Shedding new light on better-known figures such as Leon Theremin (inventor of the world’s first electronic musical instrument, the Theremin), the publication also investigates the work of a number of pioneers of electronic sound tracks using ‘graphical sound’ techniques, such as Mikhail Tsekhanovsky, Nikolai Voinov, Evgeny Sholpo and Boris Yankovsky. From V eavesdropping on pianists to the 23-string electric guitar, microtonal music to the story of the man imprisoned for pentatonic research, Noise Orchestras to Machine Worshippers, Sound in Z documents an extraordinary and largely forgotten chapter in the history of music and audio technology. -

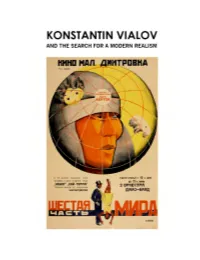

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

I from KAMCHATKA to GEORGIA the BLUE BLOUSE MOVEMENT

FROM KAMCHATKA TO GEORGIA THE BLUE BLOUSE MOVEMENT AND EARLY SOVIET SPATIAL PRACTICE by Robert F. Crane B.A., Georgia State University, 2001 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DEITRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Robert F. Crane It was defended on March 27, 2013 and approved by Atillio Favorini, PhD, Professor, Theatre Arts Kathleen George, PhD, Professor, Theatre Arts Vladimir Padunov, PhD, Professor, Slavic Languages and Literature Dissertation Advisor: Bruce McConachie, PhD, Professor, Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Robert Crane 2013 iii FROM KAMCHATKA TO GEORGIA THE BLUE BLOUSE MOVEMENT AND EARLY SOVIET SPATIAL PRACTICE Robert Crane, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 The Blue Blouse movement (1923-1933) organized thousands of workers into do-it-yourself variety theatre troupes performing “living newspapers” that consisted of topical sketches, songs, and dances at workers’ clubs across the Soviet Union. At its peak the group claimed more than 7,000 troupes and 100,000 members. At the same time that the movement was active, the Soviet state and its citizens were engaged in the massive project of building a new society reflecting the aims of the Revolution. As Vladimir Paperny has argued, part of this new society was a new spatial organization, one that stressed the horizontal over the -

God-Building As a Work Of

The following text is an edited transcription of a conversation that took place within the context of the Art and Science Aleph Festival hosted by the National Autonomous University of Mexico in May 2020 via Zoom because we were unable to gather publicly due to the Covid-19 pandemic. As part of the festival’s program, Anton Vidokle’s trilogy of 01/11 films about Russian cosmism was translated to Spanish and screened for the Mexican audience. ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊCarlos Prieto: I think it’s best to start this conversation by speaking about the role that Russian cosmism could have at this moment of crisis created by the Covid-19 pandemic. ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊAnton Vidokle: Yes, a conversation about immortality acquires a lot more meaning when Anton Vidokle and Irmgard we are in the middle of a pandemic and so many Emmelhainz people are sick and dying. I think this present moment is a bit similar to the original context that triggered cosmism: all the epidemics, God-Building as droughts, and famines in nineteenth-century Russia. But now there is also the fear of a Work of Art: planetary ecological collapse and extinction, and in this context the idea of resurrection becomes much more urgent. There is also a certain Cosmist hopelessness produced by the decline of reason and social progress, both of which have been Aesthetics encountering countless setbacks in recent decades. All of this makes the delirious optimism of cosmism meaningful and moving, in my z opinion. n i a h ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊIrmgard Emmelhainz: Here is another l e question to start from: What is Russian