Cooperative Avant-Garde: Rhetoric and Social Values of the New World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Museum of Pictorial Culture

The Museum Of Pictorial Culture From Less-Known Russian Avant-garde series Lev Manovich and Julian Sunley, 2021 Although we usually assume think that first museum of The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, 2019-2020, curated by Dr. modern art was MoMA (New York, 1929), an earlier museum Liubov Pchelkina. From the exhibition description: called Museum of Pictorial Culture was established in 1919 “2019 will mark 100 years since the implementation of the and run by most important Russian avant-garde artists until unique museum project of Soviet Russia – the creation of the its closing in 1929. Our essays discuss innovative museum Museum of Pictorial Culture, the first museum of contemporary concepts developed by these artists, and point out their art in our country… “The exhibition will present the history of the Museum of Pictorial Culture as an important stage in the history relevance to recent museum experiments in presenting their of Russian avant-garde and the history of the Tretyakov Gallery’s collections online using visualization methods. acquisitions. The exposition will reflect the unique structure of the museum. The exhibition will include more than 300 You can find our sources (including for images) and further paintings, drawings, sculptures from 18 Russian and 5 foreign reading at the bottom of the essay. The main source for this collections. For the first time, the audience will be presented essay is the the exhibition 'Museum of Pictorial Culture. To the with experimental analytical work of the museum. Unique 100th Anniversary of the First Museum of Contemporary Art’ at archival documents will be an important part of the exposition.” Room C at the original Museum of Pictorial Culture, containing works by Room C reconstructed at The Tretyakov Gallery, 2019. -

INSTRUMENTS for NEW MUSIC Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

SOUND, TECHNOLOGY, AND MODERNISM TECHNOLOGY, SOUND, THOMAS PATTESON THOMAS FOR NEW MUSIC NEW FOR INSTRUMENTS INSTRUMENTS PATTESON | INSTRUMENTS FOR NEW MUSIC Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserv- ing and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribu- tion to this book provided by the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The publisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Curtis Institute of Music, which is committed to supporting its faculty in pursuit of scholarship. Instruments for New Music Instruments for New Music Sound, Technology, and Modernism Thomas Patteson UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distin- guished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activi- ties are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institu- tions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2016 by Thomas Patteson This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY- NC-SA license. To view a copy of the license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses. -

Catalogue Reviews

Catalogue Reviews THE COSMOS OF THE RUSSIAN EL COSMOS DE LA VANGUARDIA RUSA AVANT-GARDE$UWDQG6SDFH([SORUDWLRQ Arte y Exploración Espacial 1900-1930 John E. Bowlt, Nicoletta Misler, Maria Tsantsanoglou, Editors John E. Bowlt, Nicoletta Misler, Maria Tsantsanoglou, Editors State Museum of Contemporary Art Costakis Collection, Fundación Botin, Santander, Spain 30€ Thessaloniki £30.65 / 35€ / $48.32 370 pp 117 col plates 108 in-text illus 68 264 pp. Many colour illus Bilingual Greek and English edition Articles in English translation ISBN 978 960 9409 11 7 ISBN 978-84-96655-59-0 “In the 1910s and 1920s the popular press ran countless backdrops for Victory Over the Sun of 1913. (See P. Railing and DUWLFOHV RQ VSDFH VSDFH ÀLJKW H[WUDWHUUHVWULDO OLIH SK\VLFDO C. Wallis, “Journey in Space-Time in the Vehicle of Destiny” trajectories, eclipses and so on, stimulated, no doubt, by the in A. Kruchenykh, Victory Over the Sun. Translated by Evgeny LQWHUPLWWHQWWULXPSKVRIWKH¿UVW5XVVLDQDLUSODQHEXLOGHUVSLORWV Steiner, Editor, P. Railing. Artists.Bookworks, 2009.) Artists and aerodynamicists”, write the curators of this exhibition, such as Ivan Kudriashev represented comets, but none of John E. Bowlt, Nicoletta Misler and Maria Tsantsanoglou. Rodchenko’s comet paintings are included in the exhibitions. 7KDW D FRQVHTXHQW IDVFLQDWLRQ ZLWK WKH KLJK IURQWLHU ¿UHG WKH Then there are imaginations of vehicles for space travel such LPDJLQDWLRQVRI5XVVLDQ$YDQW*DUGHDUWLVWVLVFRQ¿UPHGE\WKH as those by Georgii Kritikov, or of space cities by Klutsis in his diverse exhibits selected for these two exhibitions. series of the Dynamic City, later renamed Project for a City of 'LUHFWO\ UHODWHG WR ÀLJKW DUH ZRUNV VXFK DV 9ODGLPLU the Future. -

Download Information on the Artist and the Artwork

www.points-of-resistance.org LUTZ BECKER AFTER THE WALL (1999/2014), Sound Sculpture on loop, 37 min 18 sec, composed of 5 parts: § Potsdamer Platz: Strong atmosphere. It is the basis of the installation. Hammering and distant voices. § Invalidenstrasse: Dramatic close-up percussion of hammers. § Checkpoint Charlie: Heavy percussion. Massive rhythmical sound bundles. § Brandanburger Tor: Relaxed, regular beats quite close. § Night: End piece with dominant echos. The Berlin Wall was first breached on 9th November 1989, as the result of popular mass meetings and demonstrations within the GDR. It was not demolished at a single stroke, but over days and weeks was slowly chipped away as people from East and West joined together to obliterate a hated symbol of oppression. This was the first in a chain of events that led to the end of the Soviet Union and the Iron Curtain. Europe was freer than it had ever been before! And the ramifications spread the world-over! In 1989 the whole of Berlin rang and rocked to the liberating sound of hammers and pickaxes as the Wall was demolished. It was intended to build a better world without any walls. Artist and film-maker Lutz Becker made a montage of these percussive sounds as the opening work in After the Wall, a large exhibition of art from the post-communist countries of Europe, that opened in 1999 on the 10th anniversary of this world-changing event. Now for Points of Resistance, at Berlin’s iconic point of resistance in the Zionskirch, we encourage you to scan the barcode and listen on your phones -

Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Koenig Books Isbn 978-3-86560-706-5 Early 20Th Century Russia · Andrey Smirnov

SOUND IN Z Russia, 1917 — a time of complex political upheaval that resulted in the demise of the Russian monarchy and seemingly offered great prospects for a new dawn of art and science. Inspired by revolutionary ideas, artists and enthusiasts developed innumerable musical and audio inventions, instruments and ideas often long ahead of their time – a culture that was to be SOUND IN Z cut off in its prime as it collided with the totalitarian state of the 1930s. Smirnov’s account of the period offers an engaging introduction to some of the key figures and their work, including Arseny Avraamov’s open-air performance of 1922 featuring the Caspian flotilla, artillery guns, hydroplanes and all the town’s factory sirens; Solomon Nikritin’s Projection Theatre; Alexei Gastev, the polymath who coined the term ‘bio-mechanics’; pioneering film maker Dziga Vertov, director of the Laboratory of Hearing and the Symphony of Noises; and Vladimir Popov, ANDREY SMIRNO the pioneer of Noise and inventor of Sound Machines. Shedding new light on better-known figures such as Leon Theremin (inventor of the world’s first electronic musical instrument, the Theremin), the publication also investigates the work of a number of pioneers of electronic sound tracks using ‘graphical sound’ techniques, such as Mikhail Tsekhanovsky, Nikolai Voinov, Evgeny Sholpo and Boris Yankovsky. From V eavesdropping on pianists to the 23-string electric guitar, microtonal music to the story of the man imprisoned for pentatonic research, Noise Orchestras to Machine Worshippers, Sound in Z documents an extraordinary and largely forgotten chapter in the history of music and audio technology. -

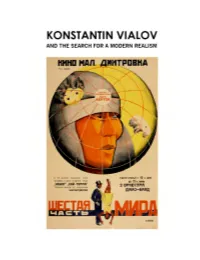

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

God-Building As a Work Of

The following text is an edited transcription of a conversation that took place within the context of the Art and Science Aleph Festival hosted by the National Autonomous University of Mexico in May 2020 via Zoom because we were unable to gather publicly due to the Covid-19 pandemic. As part of the festival’s program, Anton Vidokle’s trilogy of 01/11 films about Russian cosmism was translated to Spanish and screened for the Mexican audience. ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊCarlos Prieto: I think it’s best to start this conversation by speaking about the role that Russian cosmism could have at this moment of crisis created by the Covid-19 pandemic. ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊAnton Vidokle: Yes, a conversation about immortality acquires a lot more meaning when Anton Vidokle and Irmgard we are in the middle of a pandemic and so many Emmelhainz people are sick and dying. I think this present moment is a bit similar to the original context that triggered cosmism: all the epidemics, God-Building as droughts, and famines in nineteenth-century Russia. But now there is also the fear of a Work of Art: planetary ecological collapse and extinction, and in this context the idea of resurrection becomes much more urgent. There is also a certain Cosmist hopelessness produced by the decline of reason and social progress, both of which have been Aesthetics encountering countless setbacks in recent decades. All of this makes the delirious optimism of cosmism meaningful and moving, in my z opinion. n i a h ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊIrmgard Emmelhainz: Here is another l e question to start from: What is Russian -

Reinterpreting Malevich: Biography, Autobiography, Art

d'6tudes Slaves Canadian-American Slavic Studies,36, No. 4 (Winter 2002),405_20. vas this see- MYROSLAV SHKANDRIJ (Winnipeg, MB, Canada) f those more fiy. ) accused by rist ideology RE INTE RP RE TII{ G MAL EVIC H : tate, Kass6k BIOGRAPHY, AUTOBIOGRAPHY, nunist in its ART r need for a €r culture.4? Malevich's life and achievement have frequentiy been framed as a narrative g the Soviet that describes a revolutionary, a dismantler of Russian and European artistic con- funding in ventions, and a ..aesthetic ' harbinger of a new art of the city. The of rupture" has < helped es- been invoked in order to interpret his work as the expression of an overwhelming Lps in politi- impulse to break radically and completely with the ota society, with archaic and outdated mpassioned artistic forms, hnd with nineteenth-century populist traditions. Retrospec- position he tive exhibitions that have been mounted since lggg-9i alongside the publication of additional loyalty de- selections from his voluminous writings have stimulated some modi- fications to this interpretive matrix. He is now emerging as a figure formed not simply petersbur!{petrogrld/Leningrad conhol dur- by the atmosphere of Moscow and St. in the immediate pre- cultural re- and post-revolutionary years,r but by a muct wider sei of ex- periences. Attempts to in 1949, describe Malevich's evolution have, naturally, had to inte_ 'ly grate new perspectives.2 (along with In particular, the early life in villages and small towns and the later association with Klvan artists :position of have aftracted the attention of several critics and scholars. -

Russian Pioneers of Sound Art in the 1920S

Smirnov A., Pchelkina L., Russian Pioneers of Sound Art in the 1920s. Catalogue of the exhibition 'Red Cavalry: Creation and Power in Soviet Russia between 1917 and 1945'. La Casa Encendida, Madrid, 2011. Russian Pioneers of Sound Art in the 1920s Andrey Smirnov / Liubov Pchelkina The brief lapse in time between the 1910s and the 1930s was marked in Russia by a series of cataclysms. During this period, a country which throughout its history had imported its system of values and official culture devised totally original conceptions for the development of various technologies in numerous areas of the arts and sciences. The culture of the early 20s was very much based on principles of anarchy. Between 1917 and 1924 the traditional Russian State was almost ruined and society was structured as a sort of anarchical ‘network culture’ based on numerous cross-connected ‘creative units’ – artists, scholars, politicians, etc. In 1918, the Federation of Futurists declared: ‘Separation of Art from the State. Destruction of control over Art. Down with diplomas, ranks, official posts and grades. Universal Artistic Education.’1 This artistic Utopia coexisted with the brutal policy of War Communism, conducted by the state during the Civil War and replaced with the NEP (New Economic Policy) in 1921, when socialist ideas were combined with possibilities of free business. Although Lenin hated ‘futurists’ (after the Revolution this name was extended to almost all avant-garde arts), at the same time he suffered them. Therefore a unique opportunity arose: the State was keen to encourage art that broke with tradition and was being developed in Arseny Avraamov conducting the Symphony of Sirens, Moscow, 7.11.1923. -

Downloaded from the Web-Site

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 48, August, 2004 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca. 90089-4353, USA Tel.: (213) 740-2735 or (213) 740-6120; Fax: (213) 740-8550; E: [email protected] STATUS This is the forty-eighth biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue that appeared in February, 2004. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the spring and summer of this year. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2001 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. A full run can also be supplied on a CD disc (containing a searchable version in Microsoft Word) at a cost of $25.00, shipping included (add $5.00 if overseas airmail.) Beginning in August, the IMRC is transferring the Newsletter to an electronic format and, hence- forth, individuals and institutions on our courtesy list will receive the issues as an e-attachment. Members in full standing, however, will continue to receive hard copies of the Newsletter as well as the text in electronic format, wherever feasible. Please send us new and corrected e-mail addresses. An illustrated brochure describing the programs, collections, and functions of the IMRC is also available RUSSIA: HOW SWEET IT IS Nevsky Prospect in St. Petersburg has long been a favorite topic of literary consumption. Pushkin, Dostoevsky, and Bely were all fascinated by its magic and Gogol even entitled one of his stories "Nevsky Prospect". -

Workshop's Booklet

PROGRAM | 1 Cover: Vladimir Mayakovsky, 3. Chto eto znachit?, [digitized detail of ROSTA No. 498: Davaite i poluchite], November 1920. 2 | PROGRAM WHAT IS TO BE DONE? DISCUSSIONS IN RUSSIAN ART THEORY AND CRITICISM II The seventh graduate workshop of the Russian Art & Culture Group will focus on the main tendencies in Russian art theory from Russian modernism to the present day. We want to specifically explore responses to the question “What Is to Be Done?” [Что делать?] by artists, art critics, writers, and other members of the Russian intelligentsia, specifically reflecting upon movements such as the Russian avant- garde, neo-primitivism, constructivism, formalism, Socialist realism, and nonconformist art, and examine the use of artistic concepts such as parody, self-historization, or the center/periphery problem as well as responses to art movements from abroad, including cubism, concept art, and others. PROGRAM | 1 7th Graduate Workshop of the Russian Art & Culture Group Jacobs University Bremen and Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Bremen PROGRAM THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 19 VENUE: Jacobs University Bremen Campus Ring 1, 28759 Bremen, Lab 3 10.30 Opening: Welcome Address Prof. Dr. Isabel Wünsche, Jacobs University Bremen Panel I: EXHIBITIONS OF RUSSIAN ART IN THE WEST Chair: Miriam Leimer 11:00 Estorick, Hammer & Sickle: Soviet Cultural Exchange in the 1960s Anastasia Kurlyandtseva, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow 11:30 Revision: Russian Art and Revolution Through Definitive Exhibitions Olga Olkheft, Bielefeld Graduate School in History and Sociology, Universität Bielefeld 12.00 From Reclamation to Redefinition: No Longer Invisible Roann Barris, Radford University 12:30 Lunch Break Panel II: RESPONSES TO ARTISTIC CONCEPTS AND ART MOVEMENTS Chair: Isabel Wünsche 14:00 Realism East-West Rahma Khazam, Institut ACTE, Sorbonne Paris 1 14:30 A Failing Apology: Coming to Terms with Cubism in the Soviet Union after 1956 Kirill Chunikhin, Higher School of Economics, St. -

Figurative Art in Soviet Russia Circa 1921-1934: Situating the Realist - Anti-Realist Debate in the Context of Changing Definitions of Proletarian Culture

Figurative Art in Soviet Russia circa 1921 - 1934: situating the realist- anti-realist debate in the context of changing definitions of proletarian culture. Jacqueline Nolte Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts at the University of Cape Town. University of Cape Town March 1994 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ~ .. ,-.,, i ',/ ., .·f 7 fv1AY J .... ., ..... I.,_,., ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation is due to the financial aid rendered by The Centre for Science Development and the University of Cape Town Research Council. I wish to extend my thanks to Sandra Klapper for her dedicated and patient supervision of this dissertation. I am indebted to Evelyn Cohen for initiating me into the discipline of History of Art and for encouraging me to persevere in this field of study. I am grateful also to Helen Bradford for allowing me to participate in the Russian Revolution Honours Course in the department of History and Economic History at UCT. Acknowledgements are also due to the professional service rendered by the staff of the inter-library loan department of UCT and UCT slide librarian Alex d'Angelo. I wish, finally, to thank Antoinette Zanda for her friendship and support.