Figurative Art in Soviet Russia Circa 1921-1934: Situating the Realist - Anti-Realist Debate in the Context of Changing Definitions of Proletarian Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. MAN with a MOVIE CAMERA: the First Cinema Screening Richard Bossons

1 2. MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA: the first cinema screening Richard Bossons 2 In the spring of 1927 Dziga Vertov [1] moved to Kyiv to work for VUFKU, the All-Ukrainian Photo Cinema Adminstration [2] after being sacked by Sovkino, the Russian equivalent, for being over budget on his film ‘One Sixth of the World’ [1926], and for refusing to present a script for ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ (which he had no intention of writing). Founded in 1922 VUFKU had a reputation for much more adventurous commissioning than Sovkino, and its predecessor Goskino, training, employing, and promoting mostly Ukrainian directors and cinematographers, and their films. VUFKU was effectively closed down in 1930, merged with Soyuzkino (Sovkino’s successor) after accusations of Nationalism, Formalism and other ‘unacceptable behaviour’ by the authorities in Moscow. In less than nine years the studios had produced over 140 full length feature films, and many documentaries, newsreels and animations. Films such as Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s ‘Ukrainian Trilogy’ (‘Zvenigora’ [1928], ‘Arsenal’ [1929], ‘Earth’ (‘Zemlya’) [1930]), and Dziga Vertov’s two masterpieces, ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ and ‘Enthusiasm: the Donbas Symphony’ [1930] earned VUFKU an international reputation. It controlled all aspects of the cinematic process including film-making, film processing, screening, publicity, and education. The main studios were originally in Odesa with others in Kharkiv and Yalta. After the earthquake in Yalta in 1927 VUFKU decided to relocate its equipment to large new studios in Kyiv in 1928. These are now the home of the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Film Studio. The studio administration was also based in Kyiv at this time. -

The Centenary of Independence Two Young Peasant Women

The Centenary of Independence by Henri Rousseau Painted in 1892, this depicts the celebration of the French independence of 1792. There are peasants dancing the farandole under a liberty tree. Serious and dignified republican leaders look on at the happy people of France. The bright colors and solid figures are allegorical of the radiant and strong state of France under its good government. Two Young Peasant Women by Camille Pissaro This was painted in 1891. The artist had a desire to “educate the people” by depicting scenes of people working on farms and in rural settings. He made an effort to be realist rather than idealistic. He wanted to depict people as they really were not in order to make allegorical statements or send political messages. Exotic Landscape by Henri Rousseau This was painted in 1908 and is part of a series of jungle scenes by this artist. He purposely painted in a naive or primitive style. Though the painting looks simplistic the lay- ers of paint are built up layer by meticulous layer to give the depth of color and vibrancy that the artist desired. He didn’t even begin painting until he was in his forties, but by the age of 49 he was able to quit his regular job and paint full time. He was self taught. When Will You Marry? by Paul Gauguin The artist moved to Tahiti from his native France, looking for a simpler life. He was disappointed to find Tahiti colonized and most of the traditional lifestyle gone. His most famous paintings are all of Tahitian scenes. -

Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D) Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, PROPAGANDA, MONTAGE: Soviet Avant-Garde “We are all primitives of the 20th century” – Ivan Kliun, 1916 UNOVIS members’ aims include the “study of the system of Suprematist projection and the designing of blueprints and plans in accordance with it; ruling off the earth’s expanse into squares, giving each energy cell its place in the overall scheme; organization and accommodation on the earth’s surface of all its intrinsic elements, charting those points and lines out of which the forms of Suprematism will ascend and slip into space.” — Ilya Chashnik , 1921 I. Making “Modern Man” A. Kasimir Malevich – Suprematism 1) Suprematism begins ca. 1913, influenced by Cubo-Futurism 2) Suprematism officially launched, 1915 – manifesto and exhibition titled “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd. B. El (Elazar) Lissitzky 1) “Proun” as utopia 2) Types, and the new modern man C. Modern Woman? 1) Sonia Terk Delaunay in Paris a) “Orphism” or “organic Cubism” 1911 b) “Simultaneous” clothing, ceramics, textiles, cars 1913-20s 2) Natalia Goncharova, “Rayonism” 3) Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova stage designs II. Monuments without Beards -- Vladimir Tatlin A. Constructivism (developed in parallel with Suprematism as sculptural variant) B. Productivism (the tweaking of “l’art pour l’art” to be more socialist) C. Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower), 1921 III. Collapse of the Avant-Garde? A. 1937 Paris Exposition, 1937 Entartete Kunst, 1939 Popular Front B. -

Deloitte Art and Finance Report 2014

Art & Finance Report 2014. 2 Art & Finance Report 2014 5 Art & Finance Report 2014 7 8 Table of contents Foreword 10 Deloitte US launches an Art & Finance practice 11 Introduction 12 Key findings 14 Priorities 20 Section 1: The art market 24 - Interview: Hala Khayat–An informed view from the Middle East 52 Section 2: Art and wealth management survey 54 - General motivation and perception among wealth managers, art professionals and collectors 60 - Interview: Georgina Hepbourne-Scott–The role of art management in a family office 68 - Interview: Paul Aitken–Recent developments at Borro® 76 - Interview: Harco Van Den Oever–Why using an art advisor 82 - Freeports for valuable tangible assets 86 - Article: Jean-Philippe Drescher–Freeport and art secured lending in Luxembourg 88 Section 3: Art as an investment 90 Section 4: The online art industry 100 - Q&A with investors: Dr. Christian G. Nagel–Earlybird Venture Capital & the art market 112 - Q&A with investors: Christian Leybold–e.ventures & the art market 114 Section 5: Legal Trends 119 - Interview: Steven Schindler–Most significant recent legal developments in the art world 120 - Article: Karen Sanig–Attribution and authenticity - the quagmire 124 - Article: Pierre Valentin–Art finance - can the borrower keep possession of the art collateral? 128 - Article: Catherine Cathiard–The evolution of French regulations on investments in art and collectors’ items 132 Art & Finance Report 2014 9 Foreword Deloitte Luxembourg and ArtTactic are pleased to present the 3rd edition of the Art & Finance Report. The two first editions of the Art & Finance Report (2011 and 2013) helped us to establish a forum and platform for monitoring emerging trends and attitudes around important issues related to the Art & Finance industry. -

Museum of Pictorial Culture

The Museum Of Pictorial Culture From Less-Known Russian Avant-garde series Lev Manovich and Julian Sunley, 2021 Although we usually assume think that first museum of The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, 2019-2020, curated by Dr. modern art was MoMA (New York, 1929), an earlier museum Liubov Pchelkina. From the exhibition description: called Museum of Pictorial Culture was established in 1919 “2019 will mark 100 years since the implementation of the and run by most important Russian avant-garde artists until unique museum project of Soviet Russia – the creation of the its closing in 1929. Our essays discuss innovative museum Museum of Pictorial Culture, the first museum of contemporary concepts developed by these artists, and point out their art in our country… “The exhibition will present the history of the Museum of Pictorial Culture as an important stage in the history relevance to recent museum experiments in presenting their of Russian avant-garde and the history of the Tretyakov Gallery’s collections online using visualization methods. acquisitions. The exposition will reflect the unique structure of the museum. The exhibition will include more than 300 You can find our sources (including for images) and further paintings, drawings, sculptures from 18 Russian and 5 foreign reading at the bottom of the essay. The main source for this collections. For the first time, the audience will be presented essay is the the exhibition 'Museum of Pictorial Culture. To the with experimental analytical work of the museum. Unique 100th Anniversary of the First Museum of Contemporary Art’ at archival documents will be an important part of the exposition.” Room C at the original Museum of Pictorial Culture, containing works by Room C reconstructed at The Tretyakov Gallery, 2019. -

Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984)

1 de 2 SCULPTOR NINA SLOBODINSKAYA (1898-1984). LIFE AND SEARCH OF CREATIVE BOUNDARIES IN THE SOVIET EPOCH Anastasia GNEZDILOVA Dipòsit legal: Gi. 2081-2016 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/334701 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ca Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència Creative Commons Reconeixement Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution licence TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898 -1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 Programa de doctorat: Ciències humanes I de la cultura Dirigida per: Dra. Maria-Josep Balsach i Peig Memòria presentada per optar al títol de doctora per la Universitat de Girona 1 2 Acknowledgments First of all I would like to thank my scientific tutor Maria-Josep Balsach I Peig, who inspired and encouraged me to work on subject which truly interested me, but I did not dare considering to work on it, although it was most actual, despite all seeming difficulties. Her invaluable support and wise and unfailing guiadance throughthout all work periods were crucial as returned hope and belief in proper forces in moments of despair and finally to bring my study to a conclusion. My research would not be realized without constant sacrifices, enormous patience, encouragement and understanding, moral support, good advices, and faith in me of all my family: my husband Daniel, my parents Andrey and Tamara, my ount Liubov, my children Iaroslav and Maria, my parents-in-law Francesc and Maria –Antonia, and my sister-in-law Silvia. -

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

Shapiro Auctions

Shapiro Auctions RUSSIAN ART AUCTION INCLUDING POSTERS & BOOKS Tuesday - June 15, 2010 RUSSIAN ART AUCTION INCLUDING POSTERS & BOOKS 1: GUBAREV ET AL USD 800 - 1,200 GUBAREV, Petr Kirillovich et al. A collection of 66 lithographs of Russian military insignia and arms, from various works, ca. 1840-1860. Of varying sizes, the majority measuring 432 x 317mm (17 x 12 1/2 in.) 2: GUBAREV ET AL USD 1,000 - 1,500 GUBAREV, Petr Kirillovich et al. A collection of 116 lithographs of Russian military standards, banners, and flags from the 18th to the mid-19th centuries, from various works, ca. 1830-1840. Of varying sizes, the majority measuring 434 x 318mm (17 1/8 x 12 1/2 in.) 3: RUSSIAN CHROMOLITHOGRAPHS, C1870 USD 1,500 - 2,000 A collection of 39 color chromolithographs of Russian military uniforms predominantly of Infantry Divisions and related Artillery Brigades, ca. 1870. Of various sizes, the majority measuring 360 x 550mm (14 1/4 x 21 5/8 in.) 4: PIRATSKII, KONSTANTIN USD 3,500 - 4,500 PIRATSKII, Konstantin. A collection of 64 color chromolithographs by Lemercier after Piratskii from Rossiskie Voiska [The Russian Armies], ca. 1870. Overall: 471 x 340mm (18 1/2 x 13 3/8 in.) 5: GUBAREV ET AL USD 1,200 - 1,500 A collection of 30 lithographs of Russian military uniforms [23 in color], including illustrations by Peter Kirillovich Gubarev et al, ca. 1840-1850. Of varying sizes, the majority measuring 400 x 285mm (15 3/4 x 11 1/4 in.), 6: DURAND, ANDRE USD 2,500 - 3,000 DURAND, André. -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

Vkhutemas Training Anna Bokov Vkhutemas Training Pavilion of the Russian Federation at the 14Th International Architecture Exhibition La Biennale Di Venezia

Pavilion of the Russian Federation at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition la Biennale di Venezia VKhUTEMAS Training Anna Bokov VKhUTEMAS Training Pavilion of the Russian Federation at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition la Biennale di Venezia Curated by Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design Anton Kalgaev Brendan McGetrick Daria Paramonova Comissioner Semyon Mikhailovsky Text and Design Anna Bokov With Special Thanks to Sofia & Andrey Bokov Katerina Clark Jean-Louis Cohen Kurt W. Forster Kenneth Frampton Harvard Graduate School of Design Selim O. Khan-Magomedov Moscow Architectural Institute MARCHI Diploma Studios Moscow Schusev Museum of Architecture Eeva-Liisa Pelknonen Alexander G. Rappaport Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design Larisa I. Veen Yury P. Volchok Yale School of Architecture VKhUTEMAS Training VKhUTEMAS, an acronym for Vysshie Khudozhestvenno Tekhnicheskie Masterskie, translated as Higher Artistic and Technical Studios, was conceived explicitly as “a specialized educational institution for ad- vanced artistic and technical training, created to produce highly quali- fied artist-practitioners for modern industry, as well as instructors and directors of professional and technical education” (Vladimir Lenin, 1920). VKhUTEMAS was a synthetic interdisciplinary school consisting of both art and industrial facilities. The school was comprised of eight art and production departments - Architecture, Painting, Sculpture, Graphics, Textiles, Ceramics, Wood-, and Metalworking. The exchange -

27 Сентября 2008, Суббота, 15.00 25 Октября 2008

АУКЦИОН №73 CЛЕДУЮЩИЕ АУКЦИОНЫ: 27 сентября 2008, суббота, 15.00 25 октября 2008, суббота, 15.00 Для заочного участия или покупки на аукционе по телефону свяжитесь заранее с менеджерами галереи AUCTION # 73 NEXT AUCTIONS: September 27, 2008, Saturday, 3 P.M. October 25, 2008, Saturday, 3 P.M. For absentee bids, or telephone bids, please contact the gallery managers in advance Галерея Леонида Шишкина Основана в 1989 www.shishkingallery.ru Одна из первых частных One of the oldest and most галерей Москвы с безуп" respectable galleries with речной 20"летней репута" 20 years of reputable цией, специализируется excellence. Specializes in на Русской живописи XX Russian Art of the XX cen" века tury. С 2000 года проводит ре" Holds regular auctions of гулярные аукционы. soviet painting starting from 2000. Экспертиза, обрамление, вывоз за рубеж, консуль" Expertise, framing, delivery тации по вопросам инвес" worldwide, “investment in тирования в искусство. art” consultancy. Директор галереи и аукционист: Gallery director and auctioneer Ëåîíèä Øèøêèí Leonid Shishkin Арт"директор: Art"director: Åêàòåðèíà Áàòîãîâà Ekaterina Batogova Финансовый директор: Commercial Director: Ëþäìèëà Êîñàðåâà Liudmila Kosareva Менеджеры: Managers: Íàòàëüÿ Êîñàðåâà Natalia Kosareva Àëåêñåé Øèøêèí Alexey Shishkin Àíàñòàñèÿ Øèøêèíà Anastasia Shishkina Искусствовед: Art"historian: Òàòüÿíà Àñàóëîâà Òatiyana Asaulova Новые проекты: New projects: Åëåíà Ðóäåíêî Elena Rudenko Выпускающий редактор: Editor: Ãàëèíà Ôàéíãîëüä Galina Finegold Логистика и разрешения на вывоз: Export licenses and shipping: Ìèõàèë Äî÷âèðè Mikhail Dochviry Галерея открыта ежедневно: The gallery is opened daily: Понедельник"пятница 12.00 " 20.00 Monday"Friday 12 00 — 20 00 Суббота, воскресенье 12.00 " 17.00 Saturday, Sunday 12 00 — 17 00 Россия, Москва, 127051, Неглинная улица, д. -

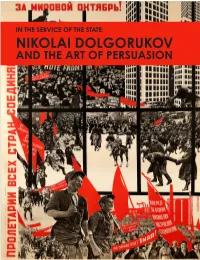

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology.