Notes and References

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Asian to Global Financial Crisis

This page intentionally left blank FROM ASIAN TO GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS This is a unique insider account of the new world of unfettered finance. The author, an Asian regulator, examines how old mindsets, market fundamental- ism, loose monetary policy, carry trade, lax supervision, greed, cronyism, and financial engineering caused both the Asian crisis of the late 1990s and the cur- rent global crisis of 2007–2009. This book shows how the Japanese zero inter- est rate policy to fight deflation helped create the carry trade that generated bubbles in Asia whose effects brought Asian economies down. The study’s main purpose is to demonstrate that global finance is so interlinked and interactive that our current tools and institutional structure to deal with critical episodes are completely outdated. The book explains how current financial policies and regulation failed to deal with a global bubble and makes recommendations on what must change. Andrew Sheng is currently the Chief Adviser to the China Banking Regulatory Commission and a Board Member of the Qatar Financial Centre Regulatory Authority, Khazanah Nasional Berhad and Sime Darby Berhad, Malaysia. He is also Adjunct Professor at the Graduate School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University, Beijing, and at the Faculty of Economics and Administration at the University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur. Mr Sheng was Chairman of the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong from 1998 to 2005. A former central banker with Bank Negara Malaysia and Hong Kong Monetary Authority, between 2003 and 2005 he was Chairman of the Technical Committee of IOSCO, the International Organization of Securities Commissions, the standard setter for securities regulation. -

2013 Collection Number

Descriptive Summary for the M.S. Swaminathan Collection Title M.S. Swaminathan Collection Date 1954 - 2013 Collection Number MS001 Creator M.S. Swaminathan (born 7 August 1925) Extent 100 Cubic Ft. Repository Archives at M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai. Abstract M.S. Swaminathan is an agricultural scientist and plant geneticist, popularly known for his work on the ‘Green Revolution in India’. A collection of his research notes, annotated drafts, correspondences and photographs makes up the M.S. Swaminathan Collection at the Archives at M.S Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF). Physical Location M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai. Language Represented in the Collection English, Hindi, Tamil and Japanese. Access The collection is open to researchers. Publication Rights Copyright is assigned to the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation. Permission for reproduction or distribution must be obtained in writing from the Archives at MSSRF. The user must obtain all necessary rights and clearances before use of material and material may only be reproduced for academic and non-commercial use. Preferred Citation Object ID, M.S. Swaminathan Collection, Archives at M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation. Acquisition Information The material was initially located at three spaces within the Foundation: Dr. Parasuraman’s cabin (Principal Scientist associated with Coastal Systems Research at the foundation and formerly, the personal secretary of M.S. Swaminathan until 2013), the Bhoothalingam library, and office of the Chairperson at the Foundation. As of Nov. 02 2020, the bulk of the material is now in the cabin next to the office of the Executive Director. Biography Monkombu Sambasivan Swaminathan is a plant geneticist, agricultural scientist and scientific administrator. -

ANNUAL REPO T 1981-82 INSTITUTE of SO EAST ASIAN STUDIES SINGAPORE I5EJI5 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies

ANNUAL REPO T 1981-82 INSTITUTE OF SO EAST ASIAN STUDIES SINGAPORE I5EJI5 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies was established as an autonomous organization in May 1968. It is a regional research centre for scholars and other specialists concerned with modern Southeast Asia . The Institute's research interest is focused on the many-faceted problems of development and modernization, and political and social change in Southeast Asia . The Institute is governed by a twenty-two-member Board of Trustees on which are represented the National University of Singapore, appointees from the government, as well as representation from a broad range of professional and civic organizations and groups. A ten man Executive Committee oversees day-to-day operations; it is chaired by the Director, the Institute's chief academic and administrative officer. Of SOUTHEAST ASIAII STUCIIES !SEAS at Heng M ui Keng Terrace, Pasir Panjang, Singapore 05 11 . Mr Brian E. Talb oys, the former New Zealand Deputy Prime Minister and Mti11ster of Foreign Affairs and Overseas Trade, arriving at the Institute to lead a Seminar on " New Zealand's Relations with Singapore and Southeast Asia". 2 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Annual Report 1 April 1981-31 March 1982 INTRODUCTION 200 books, monographs, and papers. Its library holdings have grown to almost 150,000 books, bound periodicals, microfilms, and Founded in 1968, the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, or microfiche, together with scores of newspapers and other current !SEAS for short, is an autonomous regional research centre for periodical literature. The Institute has sponsored more than 300 scholars and other specialists concerned with modern Southeast Research and Visiting Fellows, and several doctoral and Master's Asia, particularly its multi-faceted problems of development and ~Jraduate students from all over the world. -

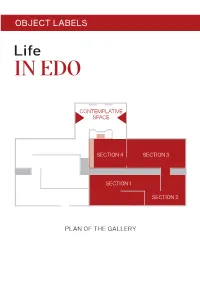

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

Hokusai's Landscapes

$45.00 / £35.00 Thomp HOKUSAI’S LANDSCAPES S on HOKUSAI’S HOKUSAI’S sarah E. thompson is Curator, Japanese Art, HOKUSAI’S LANDSCAPES at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The CompleTe SerieS Designed by Susan Marsh SARAH E. THOMPSON The best known of all Japanese artists, Katsushika Hokusai was active as a painter, book illustrator, and print designer throughout his ninety-year lifespan. Yet his most famous works of all — the color woodblock landscape prints issued in series, beginning with Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji — were produced within a relatively short time, LANDSCAPES in an amazing burst of creative energy from about 1830 to 1836. These ingenious designs, combining MFA Publications influences from several different schools of Asian Museum of Fine Arts, Boston art as well as European sources, display the 465 Huntington Avenue artist’s acute powers of observation and trademark Boston, Massachusetts 02115 humor, often showing ordinary people from all www.mfa.org/publications walks of life going about their business in the foreground of famous scenic vistas. Distributed in the United States of America and Canada by ARTBOOK | D.A.P. Hokusai’s landscapes not only revolutionized www.artbook.com Japanese printmaking but also, within a few decades of his death, became icons of art Distributed outside the United States of America internationally. Illustrated with dazzling color and Canada by Thames & Hudson, Ltd. reproductions of works from the largest collection www.thamesandhudson.com of Japanese prints outside Japan, this book examines the magnetic appeal of Hokusai’s Front: Amida Falls in the Far Reaches of the landscape designs and the circumstances of their Kiso Road (detail, no. -

Conservation of Mangrove Forest Genetic Resourceb

CONSERVATION OF MANGROVE FOREST GENETIC RESOURCEB A TRAINING MANUAL EDITED BY SANJAY v. DESHMUKH AND V. BALAJI M.S. SWAMINATHAN RESEARCH FOUNDATION CENTRE FOR RESEARCH ON SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURAL AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (CRSARD), MADRAS, INDIA INTERNATIONAL TROPICAL TIMBER ORGANISATION YOKOHAMA, JAPAN 1994 INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL STEERING COMMITTEE Prof. M.S. Swaminathan Chairman Dr. David S. Cassells mO,Japan Dr. Gary M. Burniske ITTO, Japan .Mr. R. Rajamani, lAS Secretary Ministry of Environment and Forests Government of India Representative Government of Japan Mr. Zheng Dezhang China Representative Government of Indonesia Dr. Mohamed bin Haji Ismail Malaysia Dr. H.G. Palis The Philippines Dr. KW. Sorensen UNESCO Mr. Yoshiyasu Hirayama UNEP Dr. V. Balaji Member Secretary ORGANISING COMMITTEE Chairman Prof. M.S. Swaminathan Course Director Prof. A.N. Rao Course Adviser Dr. Sanjay Deshmukh Member Dr. V. Balaji Secretariat Ms. Stella Saleth Ms. Solai Annamalai CITATION Sanjay Deshmukh and V. Balaji (Ed.s). Conservation of Mangrove Forest Genetic Resources: A Training Manual. ITTO-CRSARD Project, M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Madras, India, 1994.. @CRSARD94 Centre for Research on Sustainable Agricultural and Rural Development, Madras, India COVER Mangroves at Krusadai island, in the Gulf of Mannar Marine Biosphere Reserve, Tamil Nadu, India (Photo: Dr. Sanjay Deshmukh) COVER DESIGN AND GRAPHICS MI s. Fifth Estate Communications, Pvt. Ltd., Madras MI s. Sanka Graphics Pvt. Ltd., Madras TYPESETTING AND PRINTING Mis. SBS Laser Words Pvt. Ltd., Madras; Mis. Adyar Students Xerox Pvt. Ltd., Madras MI s. Sudarshan Graphics Pvt. Ltd., Madras; MI s. Reliance Printers Pvt. Ltd., Madras CONTENTS Page No. PREFACE ix M.S. Swaminathan CONTRIBUTORS' xi I. -

Pigments in Later Japanese Paintings : Studies Using Scientific Methods

ND 1510 ' .F48 20(}3 FREER GALLERY OF ART OCCASIONAL PAPERS NEW SERIES VOL. 1 FREER GALLERY OF ART OCCASIONAL PAPERS ORIGINAL SERIES, 1947-1971 A.G. Wenley, The Grand Empress Dowager Wen Ming and the Northern Wei Necropolis at FangShan , Vol. 1, no. 1, 1947 BurnsA. Stubbs, Paintings, Pastels, Drawings, Prints, and Copper Plates by and Attributed to American and European Artists, Together with a List of Original Whistleriana in the Freer Gallery of Art, Vol. 1, no. 2, 1948 Richard Ettinghausen, Studies in Muslim Iconography I: The Unicorn, Vol. 1, no. 3, 1950 Burns A. Stubbs, James McNeil/ Whistler: A Biographical Outline, Illustrated from the Collections of the Freer Gallery of Art, Vol. 1, no. 4, 1950 Georg Steindorff,A Royal Head from Ancient Egypt, Vol. 1, no. 5, 1951 John Alexander Pope, Fourteenth-Century Blue-and-White: A Group of Chinese Porcelains in the Topkap11 Sarayi Miizesi, Istanbul, Vol. 2, no. 1, 1952 Rutherford J. Gettens and Bertha M. Usilton, Abstracts ofTeclmical Studies in Art and Archaeology, 19--13-1952, Vol. 2, no. 2, 1955 Wen Fong, Tlie Lohans and a Bridge to Heaven, Vol. 3, no. 1, 1958 Calligraphers and Painters: A Treatise by QildfAhmad, Son of Mfr-Munshi, circa A.H. 1015/A.D. 1606, translated from the Persian by Vladimir Minorsky, Vol. 3, no. 2, 1959 Richard Edwards, LiTi, Vol. 3, no. 3, 1967 Rutherford J. Gettens, Roy S. Clarke Jr., and W. T. Chase, TivoEarly Chinese Bronze Weapons with Meteoritic Iron Blades, Vol. 4, no. 1, 1971 IN TERIM SERIES, 1998-2002, PUBLISHED BY BOTH THE FREER GALLERY OF ART AND THE ARTHUR M. -

Pacific Affairs

Pacific Affairs Vol.53, No. 1 Spring 1980 Administrative Reform and Modernization in Post-Mao China Victor C. Falkenheim 5 The Chinese Controversy Over Higher Education Jonathan Unger 29 India's Changing Role in the United Nations Stanley A. Kochanek 48 The Japanese Supreme Court and the Governance of Education Benjamin C. Duke 69 The Roots of Indochinese Civilisation: Recent Developments in the Prehistory of Southeast Asia Donn Bayard 89 La Chine Antique Revisited Review Article E.G. Pulleyblank 115 Book Reviews (listed overleaf) 120 BOOKS REVIEWED IN THIS ISSUE PEASANTSAND POLITICS.Grass Roots Reaction to Change in Asia, edited by D.B. Miller. Rodolphe De Koninck MANYREASONS WHY. The American Involvement in Vietnam, by Michael Charlton and Anthony Moncrieff. Gareth Porter THECAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF CHINA.Volume 10: Late Ch'ing, 1800-191 1, Part I, edited by John K. Fairbank. Thomas A. Metzger LANDLORDAND LABORIN LATEIMPERIAL CHINA.Case Studies from Shandong, by Jing Su and Luo Lun, translated by Endymion Wilkinson. Edgar Wickberg THEARMS OF KIANGNAN.Modernization in the Chinese Ordnance Industry, 1860-1895, by Thomas L. Kennedy. Stanley Spector THEPEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA.A Basic Handbook, compiled by James R. Townsend. William A. Joseph THEPEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA.A Documentary History of Revolutionary Change, edited by Mark Selden, with Patti Eggleston. ./ Dennis Woodward MAO:THE PEOPLE'S EMPEROR, by.Dick Wilson. Stephen Uhalley, Jr. LAWWITHOUT LAWYERS. A Comparative View of Law in China and the United States, by Victor H. Li. Douglas M. Johnston LACHINE ET LE REGLEMENTDU PREMIERCONFLIT D'INDOCHINE (GENEVE1954), by Fran~oisJoyaux. Milton Osbome A CHINESE/ENGLISHDICTIONARY OF CHINA'SRURAL ECONOMY, by Kieran Broadbent. -

Other Parts of Asia

ARNDT’S STORY . 21 OTHER PARTS OF ASIA Despite Heinz’s passion for Indonesia, it would be wrong to categorise him as merely an ‘Indonesianist’. His early Asian engagements, as we have seen, were in Malaya, Singapore and India. For the rest of his life, he retained strong academic connections and friendships in many parts of Asia. (He never went to China or to Africa; and he visited Latin America only fleetingly.) Bangkok especially interested him, largely because of his membership of the Governing Council of the UN Asian Institute for Economic Development and Planning (ADI for short). This institute was financed by contributions from the member countries of the UN Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (ECAFE), with an annual supplement from the UN Development Program (UNDP). Heinz, under the patronage of Mick Shann, was elected to the council for two terms, from 1969 to 1974. He greatly enjoyed the council’s annual Bangkok meetings. They usually occupied a couple of days, so there was plenty of time to cultivate and nourish friendships, such as with the Indonesians Widjojo and Sumarlin, and Gerry Sicat, an economist from the University of the Philippines in Manila. A social highlight of each meeting was an informal dinner at the house of U Nyun, ECAFE’s Executive Secretary. On these occasions, more serious discussions were punctuated by friendly banter, such as the light-hearted argument about which country produced the finest mangoes. Heinz observed, wryly, that he ‘did not feel called upon to bat for Queensland’. As is often the case with such bodies, the ADI was torn between teaching and research. -

Group of Chinese Porcelain: the First a Vase with A

LOW HIGH Lot Description Estimate Estimate (lot of 2) Group of Chinese porcelain: the first a vase with a red fu-lion and two black cubs; 4000 the second, a hat stand of cylindrical form, featuring birds amid flowering tree branches, base marked, largest: 11"h $ 300 - 500 Chinese enameled porcelain bowl, with a long tail pheasant amid peonies, the everted rim 4001 decorated with Buddhist treasures, base with studio mark, 6.5"w $ 150 - 250 Chinese Dayazhai style porcelain lidded jar, of a bird perched on grape vines, and with 4002 peonies on a turquoise ground, 7.5''h $ 200 - 400 4003 Chinese enameled glass cup and vase, the cup featuring chrysanthemum and a praying mantis by rocks; the vase of flowering branches and birds, base marked, 6.5''h $ 300 - 500 (lot of 3) Group of Chinese porcelain, consisting of a square sectioned teapot decorated with 4004 two beauties; a snuff bottle of figures in a landscape; together with a bowl featuring the Three Star Immortals, base with apocryphal Kangxi mark, 7.25"w $ 300 - 500 Chinese underglaze blue porcelain small stand, of trapezoidal form with poetic colophon on 4005 four sides, 4.5"h $ 200 - 400 4006 Chinese enameled porcelain Budai, seated in royal ease in a loose robe, holding an ingot in his right hand and a sack in the left, base marked 'Zeng Long Sheng Zao', 13"h $ 300 - 500 (lot of 2) Chinese underglaze blue porcelain plates, the interior walls decorated with 4007 patterned rectangles and scrolling tendrils, (chips and hairline cracks), 9.5"w $ 200 - 400 (lot of 10) Chinese underglazed blue porcelain dishes, each of two dragons in pursuit of a 4008 pearl, base with apocryphal Kangxi mark, 6''dia. -

Odano Naotake and Akita Ranga

Seven Daring Years: ◎ : Important Cultural Property ○ : Cultural Property Designated by Akita Prefecture ☆ : Cultural Property Designated by Tokyo Metropolis Odano Naotake and Akita Ranga A : Cultural Property Designated by Akita City S : Cultural Property Designated by Senboku City November 16, 2016, to January 9, 2017 K : Cultural Property Designated by Kuwana City 11/16 12/7 12/14 12/21 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ No. Title Artist Period Collection 12/5 12/12 12/19 1/9 Section 1: The Eve of Ranga 1 The Sage Ruler Shennong (Shinno) Odano Naotake Edo period (c. 1760) Private collection 2 S Yam āntaka (Daiitoku My ôô) Odano Naotake Edo period (1765) Daiitoku Shrine, Akita 3 S Beauty Beneath Cherry Blossoms Odano Naotake Edo period (1766) Kakunodate-Shinmeisha, Akita 4 Mutual Love Ishikawa Toyonobu Edo period (18th century) Suntory Museum of Art 5 Falcon Hunting Odano Naotake Edo period (18th century) Private collection 6 Goshawk Hunting Odano Naotake Edo period (18th century) Kikuan 7 Zhong Kui (Shoki) the Demon Queller Odano Naotake Edo period (18th century) Private collection Preliminary drawing (Zhong Kui (Shoki) 8 Odano Naotake Edo period (1768) Private collection the Demon Queller, on a Donkey) Scene Preliminary drawing (Waterfall, 9 Odano Naotake Edo period (1766) Private collection change Landscape) Scene Preliminary drawing (The divine general 10 Odano Naotake Edo period (1766) Private collection change quelling a Demon, and Huang Chuping) 11 Pomegranates Odano Naotake Edo period (18th century) Kikuan 12 Pine and Rock Satake Shozan Edo period (18th -

Reflections on the Floating World

Reflections on the Floating World Rossella Menegazzo Published in 2020 by Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki on the occasion of the exhibition Enchanted Worlds: Hokusai, Hiroshige and the Art of Edo Japan at Reflections on the Floating World Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki Director: Kirsten Paisley Rossella Menegazzo Curator: Rossella Menegazzo Co-ordinating curators: Sophie Matthiesson and Emma Jameson Editor: Sophie Matthiesson Managing editor: Clare McIntosh Editorial assistant: Emma Jameson Catalogue design: Hilary Moloughney ISBN: 978-0-86463-330-9 © 2020, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and the author Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki PO Box 5749 Victoria Street West Auckland 1142 Aotearoa New Zealand www.aucklandartgallery.com This text is the print version of a lecture presented by Dr Rossella Menegazzo at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki as part of the opening events for the exhibition Enchanted Worlds: Hokusai, Hiroshige and the Art of Edo Japan. Contents 6 Introduction 8 Hanging Scrolls 12 Edo and the World of Pleasure 36 Divine and Legendary Worlds 40 Nature and Landscape 44 Further Reading 45 About the Author Cover Utagawa Hiroshige Great Waves of Sōshū Shichiriga-hama1847, hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk. Private collection. Above Figure 1 Kawahara Keiga Bustling Scene of City Life circa1825, framed painting, ink and colour on silk 4 Private collection. 5 and under whose rule there was an increase in the importation of manuals, prints, etchings and products from Europe. So we cannot say Introduction that Japan was ‘completely closed’. It depended on the periods and on who was in power.