Japanese Colour{Protect Edef U00{U00}Let Enc@Update Elax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

Plant Dye Identification in Japanese Woodblock Prints

Plant Dye Identification in Japanese Woodblock Prints Michele Derrick, Joan Wright, Richard Newman oodblock prints were first pro- duced in Japan during the sixth Wto eighth century but it was not until the Edo period (1603–1868) that the full potential of woodblock printing as a means to create popular imagery for mass consumption developed. Known broadly as ukiyo-e, meaning “pictures of the float- ing world,” these prints depicted Kabuki actors, beautiful women, scenes from his- tory or legend, views of Edo, landscapes, and erotica. Prints and printed books, with or without illustrations, became an inte- gral part of daily life during this time of peace and stability. Prints produced from about the 1650s through the 1740s were printed in black line, sometimes with hand-applied color (see figure 1). These col- ors were predominantly mineral (inorganic) pigments supplemented by plant-based (organic) colorants. Since adding colors to a print by hand was costly and slowed pro- duction, the block carvers eventually hit upon a means to create a multicolor print using blocks that contained an “L” shaped groove carved into the corner and a straight groove carved further up its side in order to align the paper to be printed (see figure 2). These guides, called kento, are located Figure 1. Actors Sanjō Kantarō II and Ichimura Takenojō IV, (MFA 11.13273), about 1719 (Kyōho 4), designed by Torii Kiyotada I, and published by in the same location on each block. They Komatsuya (31.1 x 15.3 cm). Example of a beni-e Japanese woodblock ensure consistent alignment as each color print with hand-applied color commonly made from the 1650s to 1740s. -

How to Look at Japanese Art I

HOWTO LOOKAT lAPANESE ART STEPHEN ADDISS with Audrey Yos hi ko Seo lu mgBf 1 mi 1 Aim [ t ^ ' . .. J ' " " n* HOW TO LOOK AT JAPANESE ART I Stephen Addi'ss H with a chapter on gardens by H Audrey Yoshiko Seo Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers ALLSTON BRANCH LIBRARY , To Joseph Seuhert Moore Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Addiss, Stephen, 1935- How to look at Japanese art / Stephen Addiss with a chapter on Carnes gardens by Audrey Yoshiko Seo. Lee p. cm. “Ceramics, sculpture and traditional Buddhist art, secular and Zen painting, calligraphy, woodblock prints, gardens.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-8109-2640-7 (pbk.) 1. Art, Japanese. I. Seo, Audrey Yoshiko. II. Title N7350.A375 1996 709' .52— dc20 95-21879 Front cover: Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770), Girl Viewing Plum Blossoms at Night (see hgure 50) Back cover, from left to right, above: Ko-kutani Platter, 17th cen- tury (see hgure 7); Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875), Sencha Teapot (see hgure 46); Fudo Myoo, c. 839 (see hgure 18). Below: Ryo-gin- tei (Dragon Song Garden), Kyoto, 1964 (see hgure 63). Back- ground: Page of calligraphy from the Ishiyama-gire early 12th century (see hgure 38) On the title page: Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858), Yokkaichi (see hgure 55) Text copyright © 1996 Stephen Addiss Gardens text copyright © 1996 Audrey Yoshiko Seo Illustrations copyright © 1996 Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Published in 1996 by Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, New York All rights reserv'ed. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher Printed and bound in Japan CONTENTS Acknowledgments 6 Introduction 7 Outline of Japanese Historical Periods 12 Pronunciation Guide 13 1. -

Japanese Style/Western Culture

Japonisme in Print Japanese Style/Western Culture lthough part of the Museum’s series on Japanese color woodblock prints, this Aexhibition takes a different approach by recognizing the impact of Japanese images on European and American printmaking in the late-nineteenth and early- twentieth centuries. During that time Japan’s involvement with the Western world was undergoing fundamental changes. From 1867 to 1868, Japanese political rule transitioned from the military dictatorship of the shogunate to the restoration of the authority of the emperor. Under the leadership of Emperor Meiji (r. 1867–1912), Japan experienced major shifts in political and social structures, economics, technology, industry, militarization, and foreign relations, especially with the West. As a signal of its new position in global affairs, Japan sponsored a pavilion at the 1867 Parisian Exposition universelle d’art et d’industrie (Universal Exhibition of Art and Industry), the second ever international showcase of its kind. This pivotal event, along with Japan’s burgeoning global trade, exposed European and American audiences to the distinctive materials and modes of representation of Japanese art, creating a furor for things à la Japonaise. The Western works of art, decorative art, and architecture referencing or imitating Japanese styles have come to be known as Japonisme, a French term that reflects the trend’s flashpoint in Paris in 1867. Japonisme, or Japanism, came to be an essential facet in the development of Modernist aesthetics and idioms, as the European and American prints showcased here demonstrate. Félix Bracquemond (French, 1833–1914) Vanneaux et Sarcelles (Lapwings and Teals), 1862 Etching and drypoint on chine collé Transferred from the University of Missouri (X-85) Félix Bracquemond is among the earliest French artists to have ‘discovered’ Japanese color woodblock prints and to have incorporated their formal qualities into his own art. -

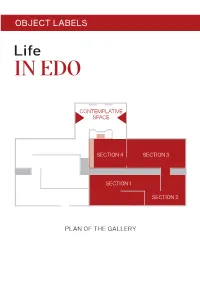

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

DOMESTIC LIFE and SURROUNDINGS: IMPRESSIONISM: (Degas, Cassatt, Morisot, and Caillebotte) IMPRESSIONISM

DOMESTIC LIFE and SURROUNDINGS: IMPRESSIONISM: (Degas, Cassatt, Morisot, and Caillebotte) IMPRESSIONISM: Online Links: Edgar Degas – Wikipedia Degas' Bellelli Family - The Independent Degas's Bellelli Family - Smarthistory Video Mary Cassatt - Wikipedia Mary Cassatt's Coiffure – Smarthistory Cassatt's Coiffure - National Gallery in Washington, DC Caillebotte's Man at his Bath - Smarthistory video Edgar Degas (1834-1917) was born into a rich aristocratic family and, until he was in his 40s, was not obliged to sell his work in order to live. He entered the Ecole des Beaux Arts in 1855 and spent time in Italy making copies of the works of the great Renaissance masters, acquiring a technical skill that was equal to theirs. Edgar Degas. The Bellelli Family, 1858-60, oil on canvas In this early, life-size group portrait, Degas displays his lifelong fascination with human relationships and his profound sense of human character. In this case, it is the tense domestic situation of his Aunt Laure’s family that serves as his subject. Apart from the aunt’s hand, which is placed limply on her daughter’s shoulder, Degas shows no physical contact between members of the family. The atmosphere is cold and austere. Gennaro, Baron Bellelli, is shown turned toward his family, but he is seated in a corner with his back to the viewer and seems isolated from the other family members. He had been exiled from Naples because of his political activities. Laure Bellelli stares off into the middle distance, significantly refusing to meet the glance of her husband, who is positioned on the opposite side of the painting. -

Hokusai's Landscapes

$45.00 / £35.00 Thomp HOKUSAI’S LANDSCAPES S on HOKUSAI’S HOKUSAI’S sarah E. thompson is Curator, Japanese Art, HOKUSAI’S LANDSCAPES at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The CompleTe SerieS Designed by Susan Marsh SARAH E. THOMPSON The best known of all Japanese artists, Katsushika Hokusai was active as a painter, book illustrator, and print designer throughout his ninety-year lifespan. Yet his most famous works of all — the color woodblock landscape prints issued in series, beginning with Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji — were produced within a relatively short time, LANDSCAPES in an amazing burst of creative energy from about 1830 to 1836. These ingenious designs, combining MFA Publications influences from several different schools of Asian Museum of Fine Arts, Boston art as well as European sources, display the 465 Huntington Avenue artist’s acute powers of observation and trademark Boston, Massachusetts 02115 humor, often showing ordinary people from all www.mfa.org/publications walks of life going about their business in the foreground of famous scenic vistas. Distributed in the United States of America and Canada by ARTBOOK | D.A.P. Hokusai’s landscapes not only revolutionized www.artbook.com Japanese printmaking but also, within a few decades of his death, became icons of art Distributed outside the United States of America internationally. Illustrated with dazzling color and Canada by Thames & Hudson, Ltd. reproductions of works from the largest collection www.thamesandhudson.com of Japanese prints outside Japan, this book examines the magnetic appeal of Hokusai’s Front: Amida Falls in the Far Reaches of the landscape designs and the circumstances of their Kiso Road (detail, no. -

How Do Katsushika Hokusai's Landscape Prints Combine Local and Transcultural Elements?

Cintia Kiss 1921312 [email protected] IMAGINING PLACE: HOW DO KATSUSHIKA HOKUSAI’S LANDSCAPE PRINTS COMBINE LOCAL AND TRANSCULTURAL ELEMENTS? A CONSIDERATION OF CULTURAL APPROPRIATION Master Thesis Asian Studies 60EC Academic year 2017-2018 Supervisor: Dr. Doreen Müller Leiden University Humanities Faculty, MA Asian Studies Track of History, Arts and Culture of Asia Specialization of Critical Heritage Studies of Asia and Europe ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Doreen Müller, whose help and insights have supported me throughout the phases of researching and writing this dissertation. Her encouraging remarks and contagious enthusiasm provided valuable assistance. Furthermore, I am grateful for the opportunity to be able to conduct my studies at Leiden University, where I could gain valuable knowledge in an international-oriented atmosphere. The variety of courses, workshops and extracurricular opportunities provided a platform to expand my vision and think critically. Lastly, I must say my thanks to my family. Their continuous encouragement, patient listening, unconditional support and love always give me courage to continue moving forward. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................. -

Marr, Kathryn Masters Thesis.Pdf (4.212Mb)

MIRRORS OF MODERNITY, REPOSITORIES OF TRADITION: CONCEPTIONS OF JAPANESE FEMININE BEAUTY FROM THE SEVENTEENTH TO THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Japanese at the University of Canterbury by Kathryn Rebecca Marr University of Canterbury 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ·········································································· 1 Abstract ························································································· 2 Notes to the Text ·············································································· 3 List of Images·················································································· 4 Introduction ···················································································· 10 Literature Review ······································································ 13 Chapter One Tokugawa Period Conceptions of Japanese Feminine Beauty ························· 18 Eyes ······················································································ 20 Eyebrows ················································································ 23 Nose ······················································································ 26 Mouth ···················································································· 28 Skin ······················································································· 34 Physique ················································································· -

Representation of Gardens in Japanese Woodblock Prints During the Edo Period

Representation of Gardens in Japanese Woodblock Prints during the Edo period. Anna Guseva, PhD. HSE, Moscow Pictures of gardens could be found in Japanese woodblock prints of different genres from bijin-ga and erotic prints to kabuki scenes and landscapes. While literal descriptions and gardening manuals are recognized as sources on the garden history, there has been little discussion about the representation of the gardens in ukiyo-e prints in spite of many examples of thoroughly depicted surroundings that can be found among them. So, this study attempts to show that ukiyo-e prints could provide miscellaneous information on gardens and their perception during the Edo period. Considering an amount of material a few criteria for selecting prints were established. This study focuses on prints where a garden is depicted as part of the surrounding environment, correlates with the represented building, and is clearly viewed from outside or inside the mansion. The analysis of the prints of such artists as Chōbunsai Eishi (1756-1829), Katsukawa Shuncho (1723-1793) Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815), and Kitagawa Utamaro (1754-1805) confirms that ukiyo-e could enrich our knowledge about the garden types, layouts, plants, as well as pastimes favoured by townspeople during the Edo period. More than that, the garden elements could be read as a visual comment to the subject itself. For example, a coloration and selection of the plants could signify the month of the year, while geomantic and Buddhist symbolism associated with gardening design could reveal some hidden meaning through the stone-and- water arrangements pictured in the print. . -

Pigments in Later Japanese Paintings : Studies Using Scientific Methods

ND 1510 ' .F48 20(}3 FREER GALLERY OF ART OCCASIONAL PAPERS NEW SERIES VOL. 1 FREER GALLERY OF ART OCCASIONAL PAPERS ORIGINAL SERIES, 1947-1971 A.G. Wenley, The Grand Empress Dowager Wen Ming and the Northern Wei Necropolis at FangShan , Vol. 1, no. 1, 1947 BurnsA. Stubbs, Paintings, Pastels, Drawings, Prints, and Copper Plates by and Attributed to American and European Artists, Together with a List of Original Whistleriana in the Freer Gallery of Art, Vol. 1, no. 2, 1948 Richard Ettinghausen, Studies in Muslim Iconography I: The Unicorn, Vol. 1, no. 3, 1950 Burns A. Stubbs, James McNeil/ Whistler: A Biographical Outline, Illustrated from the Collections of the Freer Gallery of Art, Vol. 1, no. 4, 1950 Georg Steindorff,A Royal Head from Ancient Egypt, Vol. 1, no. 5, 1951 John Alexander Pope, Fourteenth-Century Blue-and-White: A Group of Chinese Porcelains in the Topkap11 Sarayi Miizesi, Istanbul, Vol. 2, no. 1, 1952 Rutherford J. Gettens and Bertha M. Usilton, Abstracts ofTeclmical Studies in Art and Archaeology, 19--13-1952, Vol. 2, no. 2, 1955 Wen Fong, Tlie Lohans and a Bridge to Heaven, Vol. 3, no. 1, 1958 Calligraphers and Painters: A Treatise by QildfAhmad, Son of Mfr-Munshi, circa A.H. 1015/A.D. 1606, translated from the Persian by Vladimir Minorsky, Vol. 3, no. 2, 1959 Richard Edwards, LiTi, Vol. 3, no. 3, 1967 Rutherford J. Gettens, Roy S. Clarke Jr., and W. T. Chase, TivoEarly Chinese Bronze Weapons with Meteoritic Iron Blades, Vol. 4, no. 1, 1971 IN TERIM SERIES, 1998-2002, PUBLISHED BY BOTH THE FREER GALLERY OF ART AND THE ARTHUR M. -

ABSTRACT TRADITIONS Postwar Japanese Prints from the Depauw University Permanent Art Collection

ABSTRACT TRADITIONS Postwar Japanese Prints from the DePauw University Permanent Art Collection i Publication of this catalog was made possible with generous support from: Arthur E. Klauser ’45 Asian & World Community Collections Endowment, DePauw University Asian Studies Program, DePauw University David T. Prosser Jr. ’65 E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation Office of Academic Affairs, DePauw University Cover image: TAKAHASHI Rikio Tasteful (No. 5) / 1970s Woodblock print on paper 19-1/16 x 18-1/2 inches DePauw Art Collection: 2015.20.1 Gift of David T. Prosser Jr. ’65 ii ABSTRACT TRADITIONS Postwar Japanese Prints from the DePauw University Permanent Art Collection 3 Acknowledgements 7 Forward Dr. Paul Watt 8 A Passion for New: DePauw’s Postwar Print Collectors Craig Hadley 11 Japanese Postwar Prints – Repurposing the Past, Innovation in the Present Dr. Pauline Ota 25 Sōsaku Hanga and the Monozukuri Spirit Dr. Hiroko Chiba 29 Complicating Modernity in Azechi’s Gloomy Footsteps Taylor Zartman ’15 30 Catalog of Selected Works 82 Selected Bibliography 1 Figure 1. ONCHI Koshiro Poème No. 7 Landscape of May / 1948 Woodblock print on paper 15-3/4 (H) x 19-1/4 inches DePauw Art Collection: 2015.12.1 Gift of David T. Prosser Jr. ’65 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Like so many great colleges and universities, DePauw University can trace its own history – as well as the history and intellectual pursuits of its talented alumni – through generous gifts of artwork. Abstract Traditions examines significant twentieth century holdings drawn from the DePauw University permanent art collection. From Poème No. 7: Landscape of May by Onchi Kōshirō (Figure 1) to abstract works by Hagiwara Hideo (Figure 2), the collection provides a comprehensive overview of experimental printmaking techniques that flourished during the postwar years.