Khiyana Daesh, the Left and the Unmaking of the Syrian Revolution Jules Alford and Andy Wilson (Eds)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laura Chrisman - 9781526137579 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 10/02/2021 01:51:05PM Via Free Access Prelims 21/12/04 9:25 Am Page I

Laura Chrisman - 9781526137579 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/02/2021 01:51:05PM via free access prelims 21/12/04 9:25 am Page i Postcolonial contraventions Laura Chrisman - 9781526137579 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/02/2021 01:51:05PM via free access prelims 21/12/04 9:25 am Page ii For my parents, Gale and Robert Chrisman Laura Chrisman - 9781526137579 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/02/2021 01:51:05PM via free access prelims 21/12/04 9:25 am Page iii Postcolonial contraventions Cultural readings of race, imperialism and transnationalism LAURA CHRISMAN Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Laura Chrisman - 9781526137579 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/02/2021 01:51:05PM via free access prelims 21/12/04 9:25 am Page iv Copyright © Laura Chrisman 2003 The right of Laura Chrisman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication -

The United States and Russian Governments Involvement in the Syrian Crisis and the United Nations’ Kofi Annan Peace Process

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 5 No 27 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy December 2014 The United States and Russian Governments Involvement in the Syrian Crisis and the United Nations’ Kofi Annan Peace Process Ken Ifesinachi Ph.D Professor of Political Science, University of Nigeria [email protected] Raymond Adibe Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p1154 Abstract The inability of the Syrian government to internally manage the popular uprising in the country have increased international pressure on Syria as well as deepen international efforts to resolve the crisis that has developed into a full scale civil war. It was the need to end the violent conflict in Syria that informed the appointment of Kofi Annan as the U.N-Arab League Special Envoy to Syria on February 23, 2012. This study investigates the U.S and Russian governments’ involvement in the Syrian crisis and the UN Kofi Annan peace process. The two persons’ Zero-sum model of the game theory is used as our framework of analysis. Our findings showed that the divergence on financial and military support by the U.S and Russian governments to the rival parties in the Syrian conflict contradicted the mandate of the U.N Security Council that sanctioned the Annan plan and compromised the ceasefire agreement contained in the plan which resulted in the escalation of violent conflict in Syria during the period the peace deal was supposed to be in effect. The implication of the study is that the success of any U.N brokered peace deal is highly dependent on the ability of its key members to have a consensus, hence, there is need to galvanize a comprehensive international consensus on how to tackle the Syrian crisis that would accommodate all crucial international actors. -

Mao's War Against Nature: Politics and the Environment In

Reviews Mao’s War Against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China, by Judith Shapiro, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2001), xvii, 287 pp. Reviewed by Gregory A. Ruf, Associate Professor, Chinese Studies and Anthropology Stony Brook State University of New York In this engaging and informative book, Judith Shapiro takes a sharp, critical look at how development policies and practices under Mao influenced human relationships with the natural world, and considers some consequences of Maoist initiatives for the environment. Drawing on a variety of sources, both written and oral, she guides readers through an historical overview of major political and economic campaigns of the Maoist era, and their impact on human lives and the natural environment. This is a bold and challenging task, not least because such topics remain political sensitive today. Yet the perspective Shapiro offers is refreshing, while the problems she highlights are disturbing, with significant legacies. The political climate of revolutionary China was pervaded by hostile struggle against class enemies, foreign imperialists, Western capitalists, Soviet revisionists, and numerous other antagonists. Under Mao and the communists, “the notion was propagated that China would pick itself up after its long history of humiliation by imperialist powers, become self-reliant in the face of international isolation, and regain strength in the world” (p.6). Militarization was to be a vehicle through which Mao would attempt to forge a ‘New China.’ His period of rule was marked by a protracted series of mass mobilization campaigns, based around the fear of perceived threats, external or internal. Even nature, Shapiro argues, was portrayed in a combative and militaristic rhetoric as an obstacle or enemy to overcome. -

Cultural Orientation | Kurmanji

KURMANJI A Kurdish village, Palangan, Kurdistan Flickr / Ninara DLIFLC DEFENSE LANGUAGE INSTITUTE FOREIGN LANGUAGE CENTER 2018 CULTURAL ORIENTATION | KURMANJI TABLE OF CONTENTS Profile Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 Government .................................................................................................................. 6 Iraqi Kurdistan ......................................................................................................7 Iran .........................................................................................................................8 Syria .......................................................................................................................8 Turkey ....................................................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Bodies of Water ...........................................................................................................10 Lake Van .............................................................................................................10 Climate ..........................................................................................................................11 History ...........................................................................................................................11 -

Should the Un Intervene Into to Oppressive Regimes?

NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF LAW MASTER’S PROGRAM MASTER’S THESIS SHOULD THE UN INTERVENE INTO TO OPPRESSIVE REGIMES? A COMPARATIVE EXAMINATIONS OF THE LEGAL OF HUMAN RIGHT JUSTIFICATIONS FOR INTERVENING IN AFGHANISTAN AND LIBYA AND THE INACTION IN SYRIA Hadi Abdullah MAWLOOD NICOSIA 2016 NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF LAW MASTER’S PROGRAM MASTER’S THESIS SHOULD THE UN INTERVENE INTO TO OPPRESSIVE REGIMES? A COMPARATIVE EXAMINATIONS OF THE LEGAL OF HUMAN RIGHT JUSTIFICATIONS FOR INTERVENING IN AFGHANISTAN AND LIBYA AND THE INACTION IN SYRIA PREPARED BY Hadi Abdullah MAWLOOD 20135446 Supervisor Asst. Prof. Dr Resat Volkan GUNEL NICOSIA 2016 NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Department of Law Master’s Program Thesis Defence Thesis Title: Should The UN Intervene Into To Oppressive Regimes? A Comparative Examinations of The Legal Of Human Right Justifications For Intervening In Afghanistan And Libya And The Inaction In Syria We certify the thesis is satisfactory for the award of degree of Master of Law Prepared By: Hadi Abdullah MAWLOOD Examining Committee in charge Asst. Prof. Dr. Reşat Volkan Günel Near East University Thesis Supervisor Head of Law Department Dr. Tutku Tugyan Near East University Law Department ….………………… Near East University ………… Department Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Assoc. Prof. Dr. MUSTAFA SAĞSAN Acting Director iii ABSTRACT The establishment of the United Nations is for the sole reason of protecting the entire peace and for the entire human race. The protection and advancement of Human Rights as innate and enforceable rights are the known tenets behind the establishment of the United Nations. -

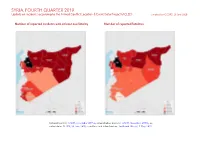

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Week 46, 10 – 16 November 2017

Week 46, 10 – 16 November 2017 General developments & political & security situation • US-led Coalition’s air force killed civilians and some paramedics in Tal Ash-Shayer area of Al-Duaiji village in rural Deir Ez-Zor, on the Syrian-Iraqi border. • Russian and US Presidents affirmed their commitment to Syria’s sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity; stressing that political settlement of the crisis would take place within framework of the Geneva process - in a joint statement issued on sidelines of the APEC summit in Vietnam. • Trump says U.S. deal with Russia on Syria will save many lives. • Moscow: Conclusions of the report of the UN-OPCW Joint Investigative Mission (JIM) on allegations of Syrian government's use of sarin gas had no basis. • Russian Defense: Russian experts are contributing to clearance of mines, left behind by ISIS, in Abu Kamal. • Zakharova: Syria's national dialogue conference is under preparation. • Algerian Prime Minister stressed that some countries in the region spent $ 130 billion to destroy Syria, Libya and Yemen. • Chinese Ambassador in Damascus stressed that a Syrian-Syrian dialogue, that guaranteed political solution, was the only way to end the crisis. • The United States has no plans to carry out military patrolling in Syria's de-escalation zones, US Defense Secretary Jim Mattis said. • The Syrian army, with support from the Russian Aerospace Forces, has recently retaken the city of Abu Kemal, the last ISIS stronghold in the eastern Syrian governorate of Deir Ezzor. • ISIS militants regained control of Abu Kemal, their last stronghold in Syria, after Iranian-backed militias who claimed to have captured the city a few days earlier. -

Into the Tunnels

REPORT ARAB POLITICS BEYOND THE UPRISINGS Into the Tunnels The Rise and Fall of Syria’s Rebel Enclave in the Eastern Ghouta DECEMBER 21, 2016 — ARON LUND PAGE 1 In the sixth year of its civil war, Syria is a shattered nation, broken into political, religious, and ethnic fragments. Most of the population remains under the control of President Bashar al-Assad, whose Russian- and Iranian-backed Baʻath Party government controls the major cities and the lion’s share of the country’s densely populated coastal and central-western areas. Since the Russian military intervention that began in September 2015, Assad’s Syrian Arab Army and its Shia Islamist allies have seized ground from Sunni Arab rebel factions, many of which receive support from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, or the United States. The government now appears to be consolidating its hold on key areas. Media attention has focused on the siege of rebel-held Eastern Aleppo, which began in summer 2016, and its reconquest by government forces in December 2016.1 The rebel enclave began to crumble in November 2016. Losing its stronghold in Aleppo would be a major strategic and symbolic defeat for the insurgency, and some supporters of the uprising may conclude that they have been defeated, though violence is unlikely to subside. However, the Syrian government has also made major strides in another besieged enclave, closer to the capital. This area, known as the Eastern Ghouta, is larger than Eastern Aleppo both in terms of area and population—it may have around 450,000 inhabitants2—but it has gained very little media interest. -

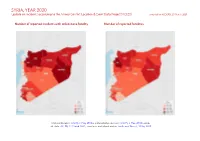

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Economic Consequences of Political Persecution

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11136 Economic Consequences of Political Persecution Radim Boháček Michal Myck NOVEMBER 2017 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11136 Economic Consequences of Political Persecution Radim Boháček CERGE-EI Michal Myck CenEA and IZA NOVEMBER 2017 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11136 NOVEMBER 2017 ABSTRACT Economic Consequences of Political Persecution* We analyze the effects of persecution and labor market discrimination during the communist regime in the former Czechoslovakia using a representative life history sample from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. -

HAS SOCIALISM FAILED? the South African Debate

HAS SOCIALISM FAILED? The South African Debate IFAA Progressive History Series Select Essays in Response to Joe Slovo’s “Has Socialism Failed?” HAS SOCIALISM FAILED? The South African Debate IFAA Progressive History Series Select Essays in Response to Joe Slovo’s “Has Socialism Failed?” Other publications in IFAA Progressive History Series o What is Marxism? o ANC Strategy and Tactics 1969 o Reconstruction and Development Plan o Has Socialism Failed o The Wretched of the Earth- The Pitfalls of National Consciousness o Conclusion to Black Skins, White Masks First published in 2017 by the Institute for African Alternatives (IFAA) 41 Salt River Road, Community House, Salt River, Cape Town 7925, South Africa Copyright ©individual authors, 2017 Editorial copyright © IFAA, 2017 Opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of IFAA and should not be taken to present the policy positions of the Institute. Editor’s Note In the early 1990’s, Francis Fukuyama claimed that the world had reached “The End of History”. For Fukuyama, the collapse of the Soviet Union spelt the end for the socialist vision of society. His views were well supported at the time. Thatcherism and Reaganism ran triumphant in the Global North, and structuraladjustment entrenched liberal free market capitalism in the Global South. The horrors of Soviet totalitarianism were becoming too clear to deny, even for the most ardent Stalinist. Was this really, then, the end of the radical left and the historic victory of liberal capitalism over its rivals? Nearly two decades later, the world has not been blessed with the fruits the “End of History” was meant to deliver. -

U.S. International Broadcasting Informing, Engaging and Empowering

2010 Annual Report U.S. International Broadcasting Informing, Engaging and Empowering bbg.gov BBG languages Table of Contents GLOBAL EASTERN/ English CENTRAL Letter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 (including EUROPE Learning Albanian English) Bosnian Croatian AFRICA Greek Afan Oromo Macedonian Amharic Montenegrin French Romanian Hausa to Moldova Kinyarwanda Serbian Kirundi Overview 6 Voice of America 14 Ndebele EURASIA Portuguese Armenian Shona Avar Somali Azerbaijani Swahili Bashkir Tigrigna Belarusian Chechen CENTRAL ASIA Circassian Kazakh Crimean Tatar Kyrgyz Georgian Tajik Russian Turkmen Tatar Radio Free Europe Radio and TV Martí 24 Uzbek Ukrainian 20 EAST ASIA LATIN AMERICA Burmese Creole Cantonese Spanish Indonesian Khmer NEAR EAST/ Korean NORTH AFRICA Lao Arabic Mandarin Kurdish Thai Turkish Tibetan Middle East Radio Free Asia Uyghur 28 Broadcasting Networks 32 Vietnamese SOUTH ASIA Bangla Dari Pashto Persian Urdu International Broadcasting Board On cover: An Indonesian woman checks Broadcasting Bureau 36 Of Governors 40 her laptop after an afternoon prayer (AP Photo/Irwin Fedriansyah). Financial Highlights 43 2 Letter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 Voice of America 14 “This radio will help me pay closer attention to what’s going on in Kabul,” said one elder at a refugee camp. “All of us will now be able to raise our voices more and participate in national decisions like elections.” RFE’s Radio Azadi distributed 20,000 solar-powered, hand-cranked radios throughout Afghanistan. 3 In 2010, Alhurra and Radio Sawa provided Egyptians with comprehensive coverage of the Egyptian election and the resulting protests. “Alhurra was the best in exposing the (falsification of the) Egyptian parliamentary election.” –Egyptian newspaper Alwafd (AP Photo/Ahmed Ali) 4 Letter from the Board TO THE PRESIDENT AND THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES On behalf of the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) and pursuant to Section 305(a) of Public Law 103-236, the U.S.